Brainstem

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2013) |

| Brainstem | |

|---|---|

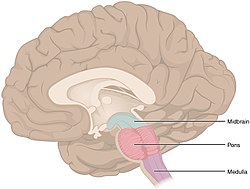

The three distinct parts of the brainstem are colored in this sagittal section of a human brain. | |

| Details | |

| Part of | Brain |

| Parts | Medulla, Pons, Midbrain |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | truncus encephali |

| MeSH | D001933 |

| NeuroNames | 2052, 236 |

| NeuroLex ID | birnlex_1565 |

| TA98 | A14.1.03.009 |

| TA2 | 5856 |

| FMA | 79876 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

The brainstem (or brain stem) is the posterior part of the brain, adjoining and structurally continuous with the spinal cord. In the human brain the brainstem includes the medulla oblongata and the pons (parts of the hindbrain), and the midbrain. Sometimes the diencephalon, the caudal part of the forebrain is included.[1]

The brainstem provides the main motor and sensory innervation to the face and neck via the cranial nerves. Of the twelve pairs of cranial nerves, ten pairs come from the brainstem. Though small, this is an extremely important part of the brain as the nerve connections of the motor and sensory systems from the main part of the brain to the rest of the body pass through the brainstem. This includes the corticospinal tract (motor), the posterior column-medial lemniscus pathway (fine touch, vibration sensation, and proprioception), and the spinothalamic tract (pain, temperature, itch, and crude touch).

The brainstem also plays an important role in the regulation of cardiac and respiratory function. It also regulates the central nervous system, and is pivotal in maintaining consciousness and regulating the sleep cycle. The brainstem has many basic functions including heart rate, breathing, sleeping, and eating.

Structure

Midbrain

The midbrain is divided into three parts. The first is the tectum, (Latin:roof), which forms the ceiling. The tectum comprises the paired structure of the superior and inferior colliculi and is the dorsal covering of the cerebral aqueduct. The inferior colliculus, is the principal midbrain nucleus of the auditory pathway and receives input from several peripheral brainstem nuclei, as well as inputs from the auditory cortex. Its inferior brachium (arm-like process) reaches to the medial geniculate nucleus of the diencephalon. Superior to the inferior colliculus, the superior colliculus marks the rostral midbrain. It is involved in the special sense of vision and sends its superior brachium to the lateral geniculate body of the diencephalon. The second part is the tegmentum which forms the floor of the midbrain, and is ventral to the cerebral aqueduct. Several nuclei, tracts, and the reticular formation are contained here. The third part, the ventral tegmentum is composed of paired cerebral peduncles. These transmit axons of upper motor neurons.

The midbrain consists of:

- Periaqueductal gray: The area of gray matter around the cerebral aqueduct, which contains various neurons involved in the pain desensitization pathway. Neurons synapse here and, when stimulated, cause activation of neurons in the nucleus raphe magnus, which then project down into the posterior grey column of the spinal cord and prevent pain sensation transmission.

- Oculomotor nerve nucleus: This is the third cranial nerve nucleus.

- Trochlear nerve nucleus: This is the fourth cranial nerve.

- Red nucleus: This is a motor nucleus that sends a descending tract to the lower motor neurons.

- Substantia nigra pars compacta: This is a concentration of neurons in the ventral portion of the midbrain that uses dopamine as its neurotransmitter and is involved in both motor function and emotion. Its dysfunction is implicated in Parkinson's disease.

- Reticular formation: This is a large area in the midbrain that is involved in various important functions of the midbrain. In particular, it contains lower motor neurons, is involved in the pain desensitization pathway, is involved in the arousal and consciousness systems, and contains the locus coeruleus, which is involved in intensive alertness modulation and in autonomic reflexes.

- Central tegmental tract: Directly anterior to the floor of the 4th ventricle, this is a pathway by which many tracts project up to the cortex and down to the spinal cord.

- Ventral tegmental area: A dopaminergic nucleus located close to the midline on the floor of the midbrain.

- Tail of the ventral tegmental area: A GABAergic nucleus located adjacent to the ventral tegmental area.

Pons

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2014) |

The pons lies between the medulla oblongata and the midbrain. It contains tracts that carry signals from the cerebrum to the medulla and to the cerebellum and also tracts that carry sensory signals to the thalamus. The pons is connected to the cerebellum by the cerebellar peduncles.

Medulla oblongata

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2014) |

The medulla oblongata often just referred to as the medulla, is the lower half of the brainstem continuous with the spinal cord. Its upper part is continuous with the pons.[2] The medulla contains the cardiac, respiratory, vomiting and vasomotor centres dealing with heart rate, breathing and blood pressure.

Ventral view of medulla and pons

In the medial part of the medulla is the anterior median fissure. Moving laterally on each side are the medullary pyramids. The pyramids contain the fibers of the corticospinal tract (also called the pyramidal tract), or the upper motor neuronal axons as they head inferiorly to synapse on lower motor neuronal cell bodies within the anterior grey column of the spinal cord.

The anterolateral sulcus is lateral to the pyramids. Emerging from the anterolateral sulci are the CN XII (hypoglossal nerve) rootlets. Lateral to these rootlets and the anterolateral sulci are the olives. The olives are swellings in the medulla containing underlying inferior nucleary nuclei (containing various nuclei and afferent fibers). Lateral (and dorsal) to the olives are the rootlets for CN IX (glossopharyngeal), CN X (vagus) and CN XI (accessory nerve). The pyramids end at the pontine medulla junction, noted most obviously by the large basal pons. From this junction, CN VI (abducens nerve), CN VII (facial nerve) and CN VIII (vestibulocochlear nerve) emerge. At the level of the midpons, CN V (the trigeminal nerve) emerges. Cranial nerve III (the occulomotor nerve) emerges ventrally from the midbrain, while the CN IV (the trochlear nerve) emerges out from the dorsal aspect of midbrain.

Between the two pyramids can be seen a decussation of fibres which marks the transition from the medulla to the spinal cord. The medulla is above the decussation and the spinal cord below.

Dorsal view of medulla and pons

The most medial part of the medulla is the posterior median sulcus. Moving laterally on each side is the fasciculus gracilis, and lateral to that is the fasciculus cuneatus. Superior to each of these, and directly inferior to the obex, are the gracile and cuneate tubercles, respectively. Underlying these are their respective nuclei. The obex marks the end of the 4th ventricle and the beginning of the central canal. The posterior intermediate sulci separates the fasciculi gracilis from the fasciculi cuneatus. Lateral to the fasciculi cuneatus is the lateral funiculus.

Superior to the obex is the floor of the 4th ventricle. In the floor of the 4th ventricle, various nuclei can be visualized by the small bumps that they make in the overlying tissue. In the midline and directly superior to the obex is the vagal trigone and superior to that it the hypoglossal trigone. Underlying each of these are motor nuclei for the respective cranial nerves. Superior to these trigones are fibers running laterally in both directions. These fibers are known collectively as the striae medullares. Continuing in a rostral direction, the large bumps are called the facial colliculi. Each facial colliculus, contrary to their names, do not contain the facial nerve nuclei. Instead, they have facial nerve axons traversing superficial to underlying abducens (CN VI) nuclei. Lateral to all these bumps previously discussed is an indented line, or sulcus that runs rostrally, and is known as the sulcus limitans. This separates the medial motor neurons from the lateral sensory neurons. Lateral to the sulcus limitans is the area of the vestibular system, which is involved in special sensation. Moving rostrally, the inferior, middle, and superior cerebellar peduncles are found connecting the midbrain to the cerebellum. Directly rostral to the superior cerebellar peduncle, there is the superior medullary velum and then the two trochlear nerves. This marks the end of the pons as the inferior colliculus is directly rostral and marks the caudal midbrain.

Development

The adult human brainstem emerges from two of the three primary vesicles formed of the neural tube. The mesencephalon is the second of the three primary vesicles, and does not further differentiate into a secondary vesicle. This will become the midbrain. The third primary vesicle, the rhombencephalon (hindbrain) will further differentiate into two secondary vesicles, the metencephalon and the myelencephalon. The metencephalon will become the cerebellum and the pons. The more caudal myelencephalon will become the medulla.

Blood supply

The main supply of blood to the brainstem is provided by the basilar arteries and the vertebral arteries.[3]

Cranial nerves

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2016) |

Ten of the twelve pairs of cranial nerves either target or are sourced from the brainstem.[4] The nuclei of the oculomotor nerve (III) and trochlear nerve (IV) are located in the midbrain. The nuclei of the trigeminal nerve (V), abducens nerve (VI), facial nerve (VII) and vestibulocochlear nerve (VIII) are located in the pons. The nuclei of the glossopharyngeal nerve (IX), vagus nerve (X), accessory nerve (XI) and hypoglossal nerve (XII) are located in the medulla. The fibers of these cranial nerves exit the brainstem from these nuclei.[5]

Function

There are three main functions of the brainstem:

- The brainstem plays a role in conduction. That is, all information relayed from the body to the cerebrum and cerebellum and vice versa must traverse the brainstem. The ascending pathways coming from the body to the brain are the sensory pathways and include the spinothalamic tract for pain and temperature sensation and the dorsal column, fasciculus gracilis, and cuneatus for touch, proprioception, and pressure sensation (both of the body). (The facial sensations have similar pathways, and will travel in the spinothalamic tract and the medial lemniscus also.) Descending tracts are upper motor neurons destined to synapse on lower motor neurons in the ventral horn and posterior horn. In addition, there are upper motor neurons that originate in the brainstem's vestibular, red, tectal, and reticular nuclei, which also descend and synapse in the spinal cord.

- The cranial nerves III-XII emerge from the brainstem.[6] These cranial nerves supply the face, head, and viscera. (The first two pairs of cranial nerves arise from the cerebrum).

- The brainstem has integrative functions being involved in cardiovascular system control, respiratory control, pain sensitivity control, alertness, awareness, and consciousness. Thus, brainstem damage is a very serious and often life-threatening problem.

Clinical significance

Diseases of the brainstem can result in abnormalities in the function of cranial nerves that may lead to visual disturbances, pupil abnormalities, changes in sensation, muscle weakness, hearing problems, vertigo, swallowing and speech difficulty, voice change, and co-ordination problems. Localizing neurological lesions in the brainstem may be very precise, although it relies on a clear understanding on the functions of brainstem anatomical structures and how to test them.

Brainstem stroke syndrome can cause a range of impairments including locked-in syndrome.

Duret haemorrhages are areas of bleeding in the midbrain and upper pons due to a downward traumatic displacement of the brainstem.[7]

Criteria for claiming brainstem death in the UK have developed in order to make the decision of when to stop ventilation of somebody who could not otherwise sustain life. These determining factors are that the patient is irreversibly unconscious and incapable of breathing unaided. All other possible causes must be ruled out that might otherwise indicate a temporary condition. The state of irreversible brain damage has to be unequivocal. There are brainstem reflexes that are checked for by two senior doctors so that imaging technology is unnecessary. The absence of the cough and gag reflexes, of the corneal reflex and the vestibulo-ocular reflex need to be established; the pupils of the eyes must be fixed and dilated; there must be an absence of motor response to stimulation and an absence of breathing marked by concentrations of carbon dioxide in the arterial blood. All of these tests must be repeated after a certain time before death can be declared.[8]

Additional images

-

The midbrain, pons, and medulla oblongata are labelled on this coronal section of the human brain.

-

Brainstem. Anterior face.Deep dissection

-

Brainstem. Posterior face.Deep dissection

See also

- Cranial nerve nucleus

- Triune brain Reptilian brain

References

- ^ Alberts, Daniel (2012). Dorland's illustrated medical dictionary (32nd ed. ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier. p. 248. ISBN 978-1-4160-6257-8.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ Dorland's (2012). Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary (32nd ed.). Elsevier Saunders. p. 1121. ISBN 978-1-4160-6257-8.

- ^ Purves, Dale (2011). Neuroscience (5. ed. ed.). Sunderland, Mass.: Sinauer. p. 740. ISBN 978-0-87893-695-3.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ Purves, Dale (2011). Neuroscience (5. ed. ed.). Sunderland, Mass.: Sinauer. p. 725. ISBN 978-0-87893-695-3.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ Vilensky, Joel; Robertson, Wendy; Suarez-Quian, Carlos (2015). The Clinical Anatomy of the Cranial Nerves: The Nerves of "On Olympus Towering Top". Ames, Iowa: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-118-49201-7.

- ^ http://vanat.cvm.umn.edu/NeuroLectPDFs/CranialN-Lect.pdf

- ^ Dorland's (2012). Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary (32nd ed.). Elsevier. p. 842. ISBN 978-1-4160-6257-8.

- ^ Black's Medical Dictionary 39th edition 1999

External links

- Comparative Neuroscience at Wikiversity

- http://www.meddean.luc.edu/lumen/Meded/Neuro/frames/nlBSsL/nl40fr.htm

- http://biology.about.com/library/organs/brain/blbrainstem.htm

- http://www.waiting.com/brainanatomy.html

- http://braininjuryhelp.com/video-tutorial/brain-injury-help-video-tutorial/

- http://www.martindalecenter.com/MedicalAnatomy_3_SAD.html

- NIF Search - Brainstem via the Neuroscience Information Framework