Bupivacaine

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /bjuːˈpɪvəkeɪn/ |

| Trade names | Marcaine, Sensorcaine, Vivacaine, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | parenteral, topical |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | n/a |

| Protein binding | 95% |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Onset of action | Within 15 min[2] |

| Elimination half-life | 3.1 hours (adults)[2] 8.1 hours (neonates)[2] |

| Duration of action | 2 to 8 hr[3] |

| Excretion | Kidney, 4–10% |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.048.993 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C18H28N2O |

| Molar mass | 288.43 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 107 to 108 °C (225 to 226 °F) |

| |

| |

| | |

Bupivacaine, marketed under the brand name Marcaine among others, is a medication used to decrease feeling in a specific area.[2] It is used by injecting it into the area, around a nerve that supplies the area, or into the spinal canal's epidural space.[2] It is available mixed with a small amount of epinephrine to make it last longer.[2] It typically begins working within 15 minutes and lasts for 2 to 8 hours.[2][3]

Possible side effects include sleepiness, muscle twitching, ringing in the ears, changes in vision, low blood pressure, and an irregular heart rate.[2] Concerns exist that injecting it into a joint can cause problems with the cartilage.[2] Concentrated bupivacaine is not recommended for epidural freezing.[2] Epidural freezing may also increase the length of labor.[2] It is a local anaesthetic of the amide group.[2]

Bupivacaine was discovered in 1957.[4] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most effective and safe medicines needed in a health system.[5] Bupivacaine is available as a generic medication and is not very expensive.[2][6] The wholesale cost in the developing world of a vial is about US$2.10.[7]

Medical uses

Bupivacaine is indicated for local infiltration, peripheral nerve block, sympathetic nerve block, and epidural and caudal blocks. It is sometimes used in combination with epinephrine to prevent systemic absorption and extend the duration of action. The 0.75% (most concentrated) formulation is used in retrobulbar block.[8] It is the most commonly used local anesthetic in epidural anesthesia during labor, as well as in postoperative pain management.[9]

Contraindications

Bupivacaine is contraindicated in patients with known hypersensitivity reactions to bupivacaine or amino-amide anesthetics. It is also contraindicated in obstetrical paracervical blocks and intravenous regional anaesthesia (Bier block) because of potential risk of tourniquet failure and systemic absorption of the drug and subsequent cardiac arrest. The 0.75% formulation is contraindicated in epidural anesthesia during labor because of the association with refractory cardiac arrest.[10]

Adverse effects

Compared to other local anaesthetics, bupivacaine is markedly cardiotoxic.[11] However, adverse drug reactions (ADRs) are rare when it is administered correctly. Most ADRs are caused by accelerated absorption from the injection site, unintentional intravascular injection, or slow metabolic degradation. However, allergic reactions can rarely occur.[10]

Clinically significant adverse events result from systemic absorption of bupivacaine and primarily involve the central nervous system (CNS) and cardiovascular system. CNS effects typically occur at lower blood plasma concentrations. Initially, cortical inhibitory pathways are selectively inhibited, causing symptoms of neuronal excitation. At higher plasma concentrations, both inhibitory and excitatory pathways are inhibited, causing CNS depression and potentially coma. Higher plasma concentrations also lead to cardiovascular effects, though cardiovascular collapse may also occur with low concentrations.[12] Adverse CNS effects may indicate impending cardiotoxicity and should be carefully monitored.[10]

- CNS: circumoral numbness, facial tingling, vertigo, tinnitus, restlessness, anxiety, dizziness, seizure, coma

- Cardiovascular: hypotension, arrhythmia, bradycardia, heart block, cardiac arrest[9][10]

Toxicity can also occur in the setting of subarachnoid injection during high spinal anesthesia. These effects include: parasthesia, paralysis, apnea, hypoventilation, fecal incontinence, and urinary incontinence. Additionally, bupivacaine can cause chondrolysis after continuous infusion into a joint space.[10]

Bupivacaine has caused several deaths when the epidural anaesthetic has been administered intravenously accidentally.[13]

Treatment of overdose

Animal evidence[14][15] indicates intralipid, a commonly available intravenous lipid emulsion, can be effective in treating severe cardiotoxicity secondary to local anaesthetic overdose, and human case reports of successful use in this way.[16][17] Plans to publicize this treatment more widely have been published.[18]

Pregnancy and lactation

Bupivacaine crosses the placenta and is a pregnancy category C drug. However, it is approved for use at term in obstetrical anesthesia. Bupivacaine is excreted in breast milk. Risks of discontinuing breast feeding versus discontinuing bupivacaine should be discussed with the patient.[10]

Postarthroscopic glenohumeral chondrolysis

Bupivacaine is toxic to cartilage and its intra-articular infusions may lead to postarthroscopic glenohumeral chondrolysis.[19]

Mechanism of action

Bupivacaine binds to the intracellular portion of voltage-gated sodium channels and blocks sodium influx into nerve cells, which prevents depolarization. Without depolarization, no initiation or conduction of a pain signal can occur.

Pharmacokinetics

The rate of systemic absorption of bupivacaine and other local anesthetics is dependent upon the dose and concentration of drug administered, the route of administration, the vascularity of the administration site, and the presence or absence of epinephrine in the preparation.[20]

- Onset of action (route and dose-dependent): 1-17 min

- Duration of action (route and dose-dependent): 2-9 hr

- Half life: neonates, 8.1 hr, adults: 2.7 hr

- Time to peak plasma concentration (for peripheral, epidural, or caudal block): 30-45 min

- Protein binding: about 95%

- Metabolism: hepatic

- Excretion: renal (6% unchanged)[10]

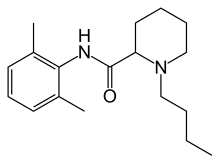

Chemical structure

Like lidocaine, bupivacaine is an amino-amide anesthetic; the aromatic head and the hydrocarbon chain are linked by an amide bond rather than an ester as in earlier local anesthetics. As a result, the amino-amide anesthetics are more stable and less likely to cause allergic reactions. Unlike lidocaine, the terminal amino portion of bupivacaine (as well as mepivacaine, ropivacaine, and levobupivacaine) is contained within a piperidine ring; these agents are known as pipecholyl xylidines.[9]

Cost

Bupivacaine is available as a generic medication and is not very expensive.[2][6] The wholesale cost of a vial of bupivacaine is about US$2.10.[7]

Research

Levobupivacaine is the (S)-(–)-enantiomer of bupivacaine, with a longer duration of action, producing less vasodilation. Durect Corporation is developing a biodegradable, controlled-release drug delivery system for after surgery. It has currently completed a phase-III clinical trial.[21]

References

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 Oct 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Bupivacaine Hydrochloride". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 2015-06-30. Retrieved Aug 1, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Whimster, David Skinner (1997). Cambridge textbook of accident and emergency medicine. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 194. ISBN 9780521433792. Archived from the original on 2015-10-05.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Egan, Talmage D. (2013). Pharmacology and physiology for anesthesia : foundations and clinical application. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders. p. 291. ISBN 9781437716795. Archived from the original on 2016-05-12.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (19th List)" (PDF). World Health Organization. April 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Hamilton, Richart (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 22. ISBN 9781284057560.

- ^ a b "Bupivacaine HCL". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Archived from the original on 5 March 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Lexicomp. "Bupivacaine (Lexi-Drugs)". Archived from the original on 2014-04-10. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Miller, Ronald D. (November 2, 2006). Basics of Anesthesia. Churchill Livingstone.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Bupivacaine (Lexi-Drugs)". Archived from the original on 2014-04-10. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ de La Coussaye, J. E.; Eledjam, J. J.; Brugada, J.; Sassine, A. (1993). "[Cardiotoxicity of local anesthetics]". Cahiers D'anesthesiologie. 41 (6): 589–598. ISSN 0007-9685. PMID 8287299.

- ^ Australian Medicines Handbook. Adelaide. 2006. ISBN 0-9757919-2-3.

- ^ ABS-CBN Interactive: Filipino nurse dies in UK due to wrong use of anaesthetic

- ^ Weinberg, GL; VadeBoncouer, T; Ramaraju, GA; Garcia-Amaro, MF; Cwik, MJ. (1998). "Pretreatment or resuscitation with a lipid infusion shifts the dose-response to bupivacaine-induced asystole in rats". Anesthesiology. 88 (4): 1071–5. doi:10.1097/00000542-199804000-00028. PMID 9579517.

- ^ Weinberg, G; Ripper, R; Feinstein, DL; Hoffman, W. (2003). "Lipid emulsion infusion rescues dogs from bupivacaine-induced cardiac toxicity". Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. 28 (3): 198–202. doi:10.1053/rapm.2003.50041. PMID 12772136.

- ^ Rosenblatt, MA; Abel, M; Fischer, GW; Itzkovich, CJ; Eisenkraft, JB (July 2006). "Successful use of a 20% lipid emulsion to resuscitate a patient after a presumed bupivacaine-related cardiac arrest". Anesthesiology. 105 (1): 217–8. doi:10.1097/00000542-200607000-00033. PMID 16810015.

- ^ Litz, RJ; Popp, M; Stehr, S N; Koch, T. (2006). "Successful resuscitation of a patient with ropivacaine-induced asystole after axillary plexus block using lipid infusion". Anaesthesia. 61 (8): 800–1. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.2006.04740.x. PMID 16867094.

- ^ Picard, J; Meek, T (February 2006). "Lipid emulsion to treat overdose of local anaesthetic: the gift of the glob". Anaesthesia. 61 (2): 107–9. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.2005.04494.x. PMID 16430560.

- ^ Gulihar, Abhinav; Robati, Shibby; Twaij, Haider; Salih, Alan; Taylor, Grahame J.S. (December 2015). "Articular cartilage and local anaesthetic: A systematic review of the current literature". Journal of Orthopaedics. 12: S200–S210. doi:10.1016/j.jor.2015.10.005. PMC 4796530. PMID 27047224.

- ^ "bupivacaine hydrochloride (Bupivacaine Hydrochloride) injection, solution". FDA. Archived from the original on 21 April 2014. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Bupivacaine Effectiveness and Safety in SABER™ Trial (BESST); "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-12-27. Retrieved 2012-03-01.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) ClinicalTrials.gov processed this record on February 29, 2012.