Byzantine Anatolia

| History of Greece |

|---|

|

|

|

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

The history of the Eastern Roman Empire (324–1453) is generally considered to fall into three distinct eras: [1]

- Late Roman Empire: 4th to 7th centuries

- Middle Byzantine Empire: 7th to 11th centuries

- Late Empire: 11th to 15th centuries

Late Roman Empire 4th–7th centuries

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (February 2013) |

Creation of the Byzantine Empire

During the late 3rd and the 4th century the sheer size of the Roman empire, as well as the pressure on its frontiers from its enemies often made it difficult for one person to govern and a practice arose of either appointing minor emperors (Caesares), or having multiple senior emperors (Augusti). In the middle of the 3rd century the empire briefly split into three, but there followed repeated cycles of division and reunification. Diocletian (284–305) established an administrative centre at Nicomedia in Bithynia. Constantine the Great 324–337 managed to reunite the empire, but having done so almost immediately set about creating a new capital in Anatolia (330) but this time chose Byzantium in Thrace, on the Bosphorus. Initially designated Nova Roma (New Rome), but then Constantinopolis in Constantine's honour (although its official title remained Nova Roma Constantinopolitana). Byzantium had long been considered of strategic importance, guarding the access from the Black Sea to the Aegean. Various emperors had either fortified or dismantled its fortifications depending on which power was using it and for what. Byzantium featured in Constantine's last war against Licinius in which Constantine had besieged the city, and after the war was over he further investigated its potential. He set about renewing the city almost immediately, inaugurating it in 330. This is a year sometimes picked as the beginning of the Byzantine Empire. The new capital was to be distinguished from the old by being simultaneously Christian and Greek (although was initially mainly Latin speaking like its Balkan hinterland) and a centre of culture. However the empire split again on his death, only to be reunited again by Theodosius I (379–395).

Theodosian dynasty 378–457

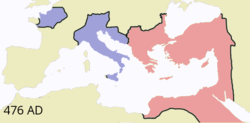

Theodosius died in Milan in 395, and was buried in Constantinople. His sons Honorius (395–423) and Arcadius (395–408) divided the empire between them and it was never again to be united. Thus the Eastern Empire was finally established by the beginning of the 5th century, as it entered the Middle Ages, while the west was to decay and Rome to be sacked under Honorius. The west limped on under a series of short lived emperors and progressively shrinking empire, in which the east frequently intervened, effectively ending with Julius Nepos (474–475).

In 395 Arcadius inherited an empire that for the first time was independent, recognised as the senior partner of the Roman World and was not the subject of territorial ambition within its frontiers. The peace engineered by his father with the Persian Sassanid Empire proved to be long lasting, taking the pressure off the eastern frontier. Although the barbarians to the north and west pose a constant threat, they concentrated their attacks on the progressively weakening western empire. He had two years previous experience of ruling as a junior Augustus under his father. Under Arcadius religious controversy continued to be a political concern of the state. He predeceased his brother in the west, being succeeded by his son Theodosius II (408-450). then only a child.

Despite some skirmishes with the Sassanids (421–422) and Huns, and a brief intervention in the western succession following the death of Honorius, Theodosius II's reign was relatively peaceful allowing him to concentrate on domestic issues. Like his father his reign was very much influenced by powerful women. In his father's reign, Theodosius' mother Aelia Eudoxia was a strong influence on policy, and in his reign, his sister Pulcheria, who was created Augusta. His domestic accomplishments included founding the University of Constantinople in 425, and codifying the laws into the Codex Theodosianus in 438. He also carried out considerable strengthening of Constantinople's walls against the threat of the Huns, following an earthquake in 448, that would serve the city well for hundreds of years. Religious controversies continued amongst the conflicting Christian theologies, and often reflected theological geopolitics within the Empire as much as doctrine. On Theodosius' death, Pulcheria married Marcian who became at least nominally emperor (450–457), and is considered a Theodosian if only by marriage.

During Marcian's reign the empire pursued an isolationist policy, leaving the western empire increasingly helpless under Barbarian attacks. Like many of his predecessors he presided over a doctrinal conference, the Council of Chalcedon (451), and is recognized as a saint.

Leonid dynasty 457–518

Leo I 457–474

When Marcian died, he left no heirs, and the throne passed to a soldier, Leo I (457–474), founder of the Leonid dynasty. As the eastern empire became progressively separated from the now crumbling west, so did its traditions and forms of administration, taking on the influences of the Hellenistic culture that preceded the Roman invasion of Anatolia. Leo was the first emperor to introduce legislation in Greek rather than Latin, and the first to be crowned by the Christian Patriarch of Constantinople. He attempted to be more interventionist in the west than Marcian, appointing the western emperor Anthemius (67–472), and leading an unsuccessful expedition against the Vandals who threatened the west. He also successfully defended Constantinople against Barbarian attacks. Leo's daughter Ariadne married Zeno, who was appointed Caesar in 473. On Leo's death, their son, Leo II (474) was only seven years old and Zeno, Leo I's son-in-law, was appointed Augustus and co-emperor. However Leo II died a few months after succeeding and Zeno, became emperor.

Civil wars and the loss of the west: Zeno, Basiliscus and Leontius 474–491

It was during the reign of Zeno (474–475; 476–484; 488–491) that the western empire finally collapsed (476), the eastern emperor becoming at least nominally responsible for the entire empire, maintaining a viceroy in Italy. Anatolia had been relatively free from internal conflict since Constantine the Great had consolidated the empire in 324. However shortly after being appointed emperor Zeno found himself faced with a usurper, Basiliscus who declared himself emperor (475–476). Zeno fled and was besieged but eventually managed to gather enough support to besiege Constantinople and retake his throne in 476. However the situation remained very unstable. In 479 he was faced with another usurper, Marcian but eventually overcame him. By 484 another usurper, Leontius (484–488) claimed the throne and was only deposed in 488 after four years of war.

Keeping peace on the borders was a constant preoccupation of Byzantine emperors, who often bought off Barbarian threats in addition to warding off actual attacks. Zeno was no exception, and often tried to play off different tribes against each other. In matters of religion Byzantine Emperors had to steer between competing versions of Christianity and in 482 Zeno attempted a compromise with his Henotikon. Zeno had no heirs at his death and although the Leonid dynasty technically ended with Leo II, Zeno was allied to them through marriage.

Anastasius I 491–518

Zeno was succeeded by Anastasius I (491–518), a palace official who allied himself in exactly the same way by marrying Ariadne, now Zeno's widow. Like his predecessor, Anastasius had to face a usurper, this time from Longinus, Zeno's brother. A long war, known as the Isaurian War ensued between 492-497, Longinus being exiled. A new challenge was the eastern frontier, relatively quiet since the time of Theodosius I, in 384. Being refused help, the Sassanids advanced into eastern Anatolia, overwhelming Theodosiopolis on the frontier in 502. This war, referred to as the Anastasian war, dragged on until 506, with neither side gaining much ground. Afterwards Anastasius ordered a major upgrade of defensive structures along the frontier. His reign saw the continuation of religious controversies that he attempted to steer between. His death marked the final end of the Leonids.

Justinian dynasty 518–602

Legend has shrouded the reasons for Justin I (518–527) being chosen as Anastasius' successor, however he was the head of Anastasius' guards, and founded the long lasting Justinian dynasty which dominated the 6th century, and was best known for the reign of its patronymic Justinian I. Justinian, as Justin's nephew, and later adopted son was amongst Justin's advisors. Some historians such as Procopius state that Justinian was the true emperor during this time, given Justin's advanced age (68) lack of education, but this is disputed. However, due to his age and health he named Justinian as co-emperor in 526.

Justin sought to resolve one of the religious controversies of the time, the Acacian schism (484–519), that divided east and west, achieving at least a temporary accommodation. The eastern front flared up again with the inconclusive Iberian War (526–532).

Justinian I 527–565

Justinian I (527–565), who succeeded Justin and was the last Latin speaking emperor, is generally regarded as the greatest of the Byzantine emperors and another Emperor-Saint. Justinian brought the empire to its greatest years of power and glory before the long decline that set in during the second half of the first millennium as western civilization moved from Late Antiquity into the High Middle Ages.

Foreign policy

Justinian's foreign policy centred around trying to recapture the lost territories of the western empire after half century of Barbarian occupation, recapturing Rome in 536. However the western operations were hampered by competing wars in the east (see below) and the outbreak of plague in 541 (see below). Rome and Italy changed hands frequently after 541 but by 554 the Byzantines were firmly in control again.

He inherited the Iberian war (526–532) with the Sassanid Empire from his predecessor and settled it in 532 with what became known as the Eternal peace of 532 but actually lasted only eight years. War broke out again in 541 but this time over another Caucasian state, Lazica rather than Iberia, hence the Lazic War (541–562). The Sassanids were forced out of Lazica and a truce signed, this time a Fifty Year Peace that lasted ten years to 572. The long peace engineered by Theodosius I in the 380s, was now to be a series of wars.

The other front that Byzantine emperors had to deal with repeatedly was the Balkans, and Constantinople was potentially vulnerable to land attacks across Thrace as well as sea attacks from either the Aegean or Black seas, and indeed was threatened in 559. The empire often used a combination of money, diplomacy and military forces to fend off incursions.

Domestic policy

Domestically he continued the codification and revision of laws begun by Theodosius II, resulting in the Corpus Juris Civilis (Body of Civil Law) including the Codex Justinianus in 534, which is still influential today, having been enacted in the Province of Italia, and thereby passing into western European law. He encouraged the development of Byzantine culture. One of his most important legacies is the great cathedral of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, commenced in 532 following the burning of the earlier church during the Nika riots of that year (see below). He was a prestigious builder and amongst other important structures was the rebuilding of the Church of the Holy Apostles, and the construction of Sts Sergius and Bacchus (527–536).

His major domestic threat came from the Nika riots in 532, which broke out following chariot racing in the Hippodrome. Sporting events were heavily politicised, and an angry mob attacked the adjacent Great Palace. The resulting fires destroyed much of the city, with large numbers of the population of Constantinople fleeing. The mob formed an alliance with Justinian's enemies in the Senate and declared a usurper, Hypatius, nephew of Anastasius I and therefore a member of the Leonid dynasty to be emperor. Justinian considered fleeing but is said to have been persuaded to stand his ground by Theodora. In the end he used stealth to divide the factions, and there was a great massacre of the rioters and Hypatius was executed.

Although his patronage allowed Byzantine culture to flourish and produced a number of notables such as Procopius the historian, this was sometimes at the expense of existing Hellenistic pagan culture.

Fiscal policy had often proved a weakness of Byzantine emperors, and trade was difficult in times of perpetual warfare. However under Justinian an indigenous silk industry developed, as well as mining of precious metals in Anatolia. While he was efficient at tax collection and raising revenues this occurred at a price, but in general the economy prospered, despite a number of earthquakes and plagues. Justinian's last years were marked by riots, plots and conspiracies. [2]

Justinian's reputation amongst his own people was very much coloured by their reaction to his favourites, whose job it was to raise the revenues for his ambitious projects. The most notable were Tribonium and John the Cappadocian. [3]

In keeping with the Byzantine tradition, women played important roles. In this case Justinian's wife and empress, the much younger courtesan Theodora (died 548) was an influential figure in Byzantine politics. [4]

Administrative reform

In his administrative reforms of 535 he tried to streamline the bureaucracy which was becoming cumbersome under the hierarchical Diocletian system of Praefecture, Diocese and Province, headed by Prefect, Vicar and Governor (consulares, correctores, or praesides) respectively. With increasing absolutism, the role of vicars and governors was becoming increasingly centrally controlled. Reducing administrative costs was the justification but was often shrouded in dubious appeals to historical tradition, and involved unforeseen consequences. Justinian transferred some vicarial powers to the governors. Anatolia was under the Praetorian prefecture of the East and comprised three dioceses, Asia in the west, Pontus in the North and The east in the south-east. He suppressed the Diocese of Asia. In Pontus he combined two provinces, Helenopontus and Pontus Polemoniacus, under a moderator Justinianus Helenoponti, but the arrangement was short lived. He also combined the two Cappadocias. He then suppressed the whole diocese, its vicar becoming the governor of Galatia Prima, but this too failed and was restored in 548. One of the problems was that provincial governors were reluctant to pursue policies that involved neighbouring jurisdictions, in the absence of an overarching diocesan government. [5] [6] [7] [8] [9]

Ecclesiastical policy

In matters of religion Justinian continued the Byzantine tradition of imposing compromises that pleased no one. Byzantine emperors became involved in doctrinal disputes and ecclesiastical politics like few other rulers before or after, and continued a series of conferences and councils to thrash out the official position. The Second Council of Constantinople in 553 constituted the fifth of the ecumenical councils that had started in Nicea in 325 under Constantine the Great, and established the paramount position of the emperor. Increasingly the eastern sensibilities in matters of religion impacted on relations with Rome and the pact, which the emperors strove to preserve. In his uncle's time he had played a part in the repair of the Acacian schism (484–519), but Rome which he consistently acknowledged as the senior ecclesiastical partner proved yet another faction to be appeased along with the diverse factions within the east such as Monophysitism, a situation which repeatedly proved impossible. Suppressing paganism proved more feasible, at least in Anatolia, while the Jewish population found their activities restricted.

Legacy

Despite his achievements many of his hard won gains were transitory, and following the great plague (541-542) signs of the decline of empire became evident. He had stretched the resources of empire to its limit and had to impose severe taxation. His contemporaries were divided and ambivalent about his true legacy. [10] He died childless, the throne passing to his nephew Justin II (565-–578).

Justinian's successors 565–602

Justin II (565–578) inherited both the strengths and weaknesses of his uncle's empire. More rigid than Justinian he decided to discontinue payments to neighbouring states although pragmatically the treasury was exhausted. This policy proved disastrous. Italy was lost once again as the Lombards overran it. In the East war with the Sassanids flared again in 572 and was to continue through the reigns of three emperors. This time an Armenian revolt against Sassanid rule precipitated conflict. Setbacks in this war were said to contribute to the failure of Justin's fragile health. In any case by 574 he abdicated, his wife Sophia and a general, Tiberius acting as regents until his death in 578.

Tiberius II Constantine (578–582) became a Justinian emperor by being adopted by Justin. Both eastern and western wars dragged on during this time. He was noted for his liberal fiscal policy and tax relief, and even criticised for squandering the treasury surpluses that Justin had accumulated. He was succeeded by another general, Maurice, who allied himself to the dynasty by becoming betrothed to Tiberius' daughter Constantina.

Maurice (582–602) had been appointed Caesar, by Tiberius in 582. [11] He continued the wars on two fronts but overstrained the resources of the empire, however he was able to bring the long running war against the Persian Sassanids (572–591) to a satisfactory conclusion largely due to civil war in Persia in which the Byzantine's intervened earning the gratitude of the victorious faction. War in the west and the Balkans went less well until the Persian matter was concluded, and was finally settled in the Balkans in 602, while separate administrations (exarchates) were established with the intention of once again dividing the empire amongst his sons.

After the relatively stable succession of the Justinians and their predecessors, his violent end at the hands of the usurper Phocas marked not just the end of the 6th century but the closing of the final chapter of classical antiquity, as the empire slipped into chaos once again.

Middle Byzantine Empire 7th–11th centuries

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (February 2013) |

The loss of Empire: Phocas and the Heraclian dynasty 602–711

At the opening of the 7th century, the Eastern Roman Empire had so evolved and departed from its Roman origins that it was now a distinct Byzantine Empire, as it transitioned from late antiquity into the Middle Ages, more Greek than Roman. Maurice had re-established the empire's frontiers, but this was not to last very long.

Phocas 602–610

Phocas (602–610) had introduced a level of violence not seen since the Constantinian wars. A representative of disgruntled soldiery he proved initially popular by reducing taxes, but soon saw the military gains of his predecessor on both the Balkan and eastern frontiers collapse. He faced one usurper, crowned by the Sassanids, and a divided military, but the final episode was the revolt of Heraclius in 608. Phocas' excesses and cruelty had made him few friends and he was soon deserted and killed by Heraclius in 610.

Heraclian dynasty 610–711

Heraclius 610–641

Heraclius (610–641) completed the transition from Roman to Byzantine Empire by making Greek the official language of empire.

He inherited the Persian onslaught brought about by his predecessor's actions. Although the Byzantines eventually triumphed by 627, the war left both sides exhausted and vulnerable to the ambitions of surrounding states. He restored stability to the empire and founded a dynasty that was to last 100 years. Meanwhile, in the east a new force had emerged unnoticed in Arabia under the Islamic prophet Muhammad. Expanding into the adjacent Persian lands, the Arabs inflicted a series of crushing blows between 633 and 642 that effectively ended Sassanid rule, and became an immediate threat to the Byzantine empire. Syria was invaded in 634 and lost by 638 defeating Heraclius' brother Theodore, followed by Armenia and Egypt. These losses were compounded by further losses of territories in the west, resulting in a rapid contraction of the frontiers. The loss of Syria was not only permanent and brought the invaders well into the Anatolia heartland. Thus a long war of attrition was initiated that was to last until the 11th century. Paradoxically, unable to resolve the continuing theological geopolitical disputes, the issue was resolved by the Muslim conquest of the south which was the centre of one side in the controversy - Monophysitism.

Heraclius left his empire to two of his sons, Constantine III and Heraklonas. The older Constantine (641), who had been made co-emperor at birth, died unexpectedly within a few months, leaving his step-brother Heraklonas (641) as sole emperor and ensuing instability during which Heraklonas was forced to accept Constantine's son Constans II as co-emperor, before being deposed and exiled within months, Constans then becoming sole emperor (641–668) although he was only 15.

Heraclius' successors 641–711

Constans saw the completion of the Arab conquests in his reign, who were soon raiding Cappadocia sacking the capital, Caesarea Mazaca (historic Kultupe, modern Kayseri) in 647, and Phrygia in 648. Arab offensives in Cilicia and Isauria forced Constans to negotiate a truce in 651 or lose western Anatolia. He also had to deal with Slavs in the Balkans, and waged war in the west.

In religious matters he was preoccupied with the Monothelitism issue, which divided east and west and brought him into conflict with the Roman popes. Becoming increasingly unpopular he was assassinated amongst rumours that he would move the capital of the empire back to the west.

Constans's son Constantine IV (668–685) had been made co-emperor in 654, and ruled in the east while his father campaigned in the west (662–668), succeeding him on the latter's death. Almost immediately he had to deal with Arab attacks on Amorium in Phrygia in 646 and Chalcedon in Bithynia. This was followed by the capture of Cyzicus in Mysia 670, as well as Smyrna and other coastal cities, finally attacking Constantinople itself in 674. This First Siege of Constantinople demonstrated how vulnerable the city was to attack, but also its strengths which ultimately prevailed, the Arabs lifting the siege in 678, and after further setbacks signing another truce which allowed Constantine to concentrate on the Balkan threat. For a long time the Danube in the Balkans had been considered the frontier that must be defended to maintain the integrity of Thrace. Now a new Slavic threat, the Bulgars crossed the Danube and inflicted heavy losses on the Byzantines in 681. Faced with the uncompromising religious controversy that had perplexed his father he convened another ecumenical council, the sixth (Third Council of Constantinople) in 680, which condemned Monotheletism. He also initiated a series of civil and military reform to cope with the shrunken and threatened empire. This was to do away with the original system of provinces with a new administrative structure based on themata (themes), the remaining parts of Anatolia being divided amongst seven themata. When he died in 668 he was succeeded by his son, Justinian II (685–695, 705–711), co-emperor since 681.

Justinian was an ambitious ruler eager to emulate his illustrious ancestor, Justinian I. However his more limited resources and despotic nature ultimately proved his downfall as the last of the Heraclians. Initially he was able to continue his father's successes in the east leaving him free to concentrate on the Balkans where he was also successful. He then returned to the east but was soundly defeated at the Battle of Sebastopolis in 692. Theologically he pursued non-orthodox thinking and convened another council in Constantinople. in 692. Domestically he continued the organisation of the themata, however his land and taxation policies met with considerable opposition, eventually provoking a rebellion led by Leontios (695–698) in 695, which deposed and exiled him, precipitating a series of events that led to a prolonged period of instability and anarchy, with seven emperors in twenty-two years. [12]

Leontios proved equally unpopular and was in turn overthrown by Tiberios III (698–705). Tiberios managed to bolster the eastern frontier and reinforced the defences of Constantinople, but meanwhile Justinian was conspiring to make a comeback and after forming an alliance with the Bulgars succeeded in taking Constantinople and executing Tiberios.

Justinian then continued to reign for a further six years (705–711). His treatment of Tiberios and his supporters had been brutal and he continued to rule in a manner that was despotic and cruel. He lost the ground regained by Tiberios in the east, and imposed his views on the Pope. However, before long he faced a rebellion led by Philippikos Bardanes (711–713). Justinian was captured and executed as was his son and co-emperor, Tiberius (706–711), thus extinguishing the Heraclian line. Justinian had taken the Byzantine empire yet further from his origins. He effectively abolished the historical role of Consul, merging it with Emperor, thus strengthening the Emperors' constitutional position as absolute monarch.

The non-dynastic years of anarchy 711–717

The years 711 to 717 were a troublesome time between the two dynasties, Heraclian and Isaurian and reflect a loss of leadership that had occurred under Justinian II, and could equally be dated from his first deposition in 695.

Philipikos' rebellion extended beyond politics to religion, deposing the Patriarch, reestablishing Monothelitism and overturning the Sixth Ecumenical Council, which in turn alienated the empire from Rome. Militarily the Bulgars reached the walls of Constantinople, and moving troops to defend the capital allowed the Arabs to make incursions in the east. His reign ended abruptly when an army rebellion deposed him and replaced him with Anastasius II (713–715).

Anastasius reversed his predecessor's religious policies and responded to Arab attacks by sea and land, this time reaching as far as Galatia in 714, with some success. However the very army that had placed him on the throne (the Opsikion army) rose against him, proclaimed a new emperor and besieged Constantinople for six months, eventually forcing Anastasius to flee.

The troops had proclaimed Theodosius III (715–717) as the new emperor, and once he had overcome Anastasius was almost immediately faced with the Second Arab siege of Constantinople (717–718), forcing him to seek assistance from the Bulgars. He in turn faced rebellion from two other themata, Anatolikon and Armeniakon in 717, and chose to resign, being succeeded by Leo III (717–741) bringing an end to the cycle of violence and instability.

It was surprising that the Byzantine Empire was able to survive, given its internal conflicts, the speedy collapse of the Sassanid Empire under Arab threat, and it was being threatened simultaneously on two fronts. However the strength of the military organisation within the empire, and factional struggles within the Arab world enabled this situation.

Iconoclasm: Isaurian dynasty 717–802

Leo III (717–741), a general from Isauria, restored order and stability to the empire, and the dynasty he founded, known as the Isaurians, was to last for nearly a century.

Leo III 717–741

Having overthrown Theodosius, the first problem Leo faced was the Arab siege of Constantinople, which was abandoned in 718, Leo having continued his predecessors alliance with the Bulgars. His next pressing task was to consolidate his power to avoid being himself deposed and to restore order in the face of the chaos that had ensued from the years of civil strife. And indeed the need to do so became clear in 719 when the deposed Anastasius II led an unsuccessful rebellion against him. Anastasius was executed. He then needed to secure the frontiers. In terms of domestic policies he embarked on a series of civil and legal reforms. The latter included a new codification in 726, referred to as the Ecloga, which unlike Justinian's Corpus on which it was based, was in Greek rather than in Latin. Administratively he subdivided a number of the themata, for reasons similar to that of his predecessors, smaller units meant less power to local officials and less threat to central authority. [13] When Leo died he was succeeded by his son, Constantine V (741–775).

Iconclasm 730–842

One of the most significant influences of Leo III was his involvement with the Iconoclastic movement in about 726. This controversy, the removal and destruction of religious icons in favour of simple crosses, and the persecution of icon worshippers was to have a profound effect on the empire, its religion and culture over most of the next century before being finally laid to rest in 842. Leo's exact role has been debated [14] An opponent of image worship has been referred to as an εἰκονοκλάστης (iconoclast), while those supporting image worship have been variously described as εἰκονολάτραι (iconolaters), εἰκονόδουλοι (iconodules) or εἰκονόφιλοι (iconophiles).

The traditional view was that Leo III issued an edict ordering the removal of images in 726, followed by prohibiting the veneration of images, but the controversy had existed in the church for some time and received some impetus from the rise of proximity of Islam and its attitude to imagery. The iconoclastic movement in the east considerably exacerbated the rift between it and the western church. The first phase of iconoclasm coincided with the Isaurian dynasty, from the edict of Leo III to Irene and the Second Council of Nicaea (Seventh Ecumenical Council) in 787. Iconoclasm was then revived by Leo V, and it persisted until 842 in the reign of Michael III (842–867) and regency of Theodora.

Leo's successors 741–802

Constantine V (741–775) had a less successful reign than his father, for no sooner had he ascended the throne than he was attacked and defeated by his brother in law, Artabasdos who proceeded to seize the title resulting in civil war between the forces of the two emperors, who had divided the themata between them. However Constantine managed to overcome his adversary by 743. The conflict was at least in part one over icons, Artabasdos being supported by the iconodule faction.

Under Constantine, Iconoclasm became further entrenched following the Council of Hieria in 754, followed by a concerted campaign against the iconodules and the suppression of monasteries which tended to be the centre of iconophilia. He continued his father's reorganisation of the themata and embarked on aggressive and expensive foreign wars against both the Arabs and Bulgars. He died campaigning against the latter, being succeeded by his son, Leo IV.

Leo IV (775–780) also had to put down uprisings, in his case his half-brothers. His marriage epitomised the conflict in Byzantine society over icons, raised an iconoclast himself, he married Irene an iconodule, resulting in a more conciliatory policy. Like his predecessors he had to defend his borders against both Arab and Bulgar, and like his father died campaigning against the Bulgars.

When Leo died his son, Constantine VI (780–797) was coemperor but only nine years old, and reigned with his mother Irene as regent. An unpopular ruler even after gaining majority he was engaged in power struggles with his mother who had been declared empress. Eventually his mother's supporters deposed him, leaving her as sole empress.

Irene (797–802), therefore was empress consort (775–780), empress dowager and regent (780–797) and empress regnant (797–80). As sole empress she was able to officially restore icon veneration during her regency in 787 by means of the Seventh Ecumenical Council, although unofficially this had been the case since 781. A female head of state was not acceptable to the western church who promptly crowned an alternative emperor (Charlemagne) in 800 further deepening the rift between east and west. With Irene ended the Isaurian dynasty when she was deposed by a patrician conspiracy.

Nikephorian dynasty 802–813

Following the deposition of Irene, there was founded a relatively short-lived dynasty for the era, the Nikephorian dynasty. The empire was in a weaker and more precarious position than it had been for a long time and its finances were problematic. [15] During this era Byzantium was almost continually at war on two frontiers which drained its resources, and like many of his predecessors, Nikephoros (802–811) himself died campaigning amongst the Bulgars to the north. Furthermore, Byzantium's influence continued to wane in the west with the formation of a new empire in the west under Charlemagne (800–814) in 800.

Nikephoros I 802–811

Nikephoros had been the empire's finance minister and on Irene's deposition immediately embarked on a series of fiscal reforms. His administrative reforms included re-organisation of themata. He survived a civil war in 803 and like most of the Byzantine emperors, he found himself at war on three fronts, suffered a major defeat at the Battle of Krasos in Phrygia in 805 and died on a campaign against the Bulgarians.

Nikephoros' successors 811–813

On Nikephoros' death, he was succeeded by his son and coemperor, Staurakios (811). However he was severely wounded in the same battle in which his father died, and after much controversy regarding the succession was persuaded to abdicate later that year by his sister's husband, Michael I (811–813), who succeeded him.

Michael I pursued more diplomatic than military solutions, however having survived the battle against Krum of Bulgaria that took the lives of his two predecessors, he engaged Krum once more and once more was defeated, severely weakening his position. Aware of a likely revolt he chose to abdicate given the grisly fate of so many prior overthrown emperors, ending the brief dynasty of Nikephoros.

Leo V and the Phrygians 820–867

The Nikephorian dynasty was overthrown by a general, Leo V (813–820), suspected of treachery in the Battle of Versinicia (813) in which the Byzantines under Michael I were routed by the Bulgarians. [16] Leo had already played a checkered role in imperial politics, rewarded by Nikephoros I for switching sides in the 803 civil war, and possibly later punished for a subsequent transgression, he had been appointed Governor of the Anatolic theme from which he was able to orchestrate Michael's downfall and his own succession.

Leo V 813–820

Leo's first task was to deal with the Bulgarian situation, who now occupied most of Thrace and were blockading Constantinople. Eventually he was able to conclude a peace treaty in 815, to the long running Byzantine-Bulgarian wars.

In religious matters, despite early evidence of image veneration, he adopted iconoclasm, this precipitating the second phase of the divisive controversy (814–842). He appears to have been motivated by the observation that the return of image veneration coincided with a period of untimely ends of emperors. He made this official through the Council of Constantinople in 815.

His downfall was the jailing of one of his generals, Michael the Amorian, on suspicion of conspiracy. Michael then organised the assassination of Leo, and assumed power as Michael II (820–829).

The Phrygian (Amorian) dynasty 820-867

The interlude of Leo V was followed by yet another short lived dynasty, variously referred to as the Phrygian or Amorian dynasty after Michael II, who like Leo came from Amorium (Phrygia), the capital of the Anatolic theme.

Michael II 820–829

No sooner had Michael deposed Leo, than he was confronted with revolt by a fellow military commander, Thomas the Slav, who claimed the throne. The ensuing civil war dragged on until 824, including a siege of Constantinople, when Thomas was defeated and killed. Michael continued the iconoclastic policy of Leo. When he died in 867 he was succeeded by his son and coemperor, Theophilus (829–842).

Theophilus 829–842

Theophilus was now faced with a flare-up of the Byzantine-Arab wars, the Arab forces once again demonstrating their ability to penetrate deep into Anatolia and inflict significant losses on the Byzantine, if short lived, and vice versa. A significant Arab triumph was the sacking of the dynastic capital of Amorium in 838. When he died in 842, he was succeeded by his son Michael III (842–867).

The demise of iconoclasm: Michael III 842–867

Michael III however was only two years old, so effective control fell to his mother, Theodora as regent (842–856). In 856 she was deposed from the regency with at least the acquiescence of Michael, by his uncle Bardas, who became very influential, and was eventually appointed Caesar that year. Another influential figure was Basil the Macedonian.

Theodora, like her predecessor Irene lost no time in putting an end to the iconoclastic movement once and for all.

During his reign important administrative reforms and reconstruction were undertaken.

Michael's reign included the usual wins and losses on the Arab front. However, despite Leo V's treaty with the Bulgarians of 815, the empire was once again at war in the Balkans in 855. However the subsequent conversion of the Bulgarians to Christianity and the peace of 864 brought a long lasting lull in the Bulgarian wars. A new threat emerged further north in 860 with the appearance of the Kievan Rus' and subsequent Rus'-Byzantine Wars of 860.

Basil then arranged to murder Bardas in 866, and was adopted by Michael and crowned co-emperor a few months later. Michael and Basil were entangled in a complex sexual melange involving Michael's mistress Eudokia Ingerina, and his sister Thekla. Michael also appointed, or announced he was going to appoint as co-emperor, Basiliskianos. This so alarmed Basil, in terms of potentially threatening the line of succession of which he was now the direct heir, that he had both Michael and Basiliskianos murdered, and ascended the throne as Basil I (867–886).

Macedonian dynasty 867–1056

While Basil I's violent murder of the reigning emperor, Michael III and his potential rival for succession, Basilikianos, ended the Phrygian dynasty and replaced it with the relatively long running Macedonian dynasty, the situation is more complicated. Michael and adopted Basil and made him coemperor, a device commonly employed by emperors to sustain the continuity of dynasties. Furthermore, a later Macedonian emperor, Leo VI was widely believed to actually be Michael III's illegitimate son by his mistress Eudokia Ingerina. Since Eudokia was also the wife of Basil I, and hence empress, Leo's paternity can be considered in doubt, being born in 866 before Michael's death. Furthermore, there is a historical continuity between the two dynasties in terms of the development of the empire.

In either case the Macedonians were to rule Anatolia and the empire for two centuries and oversee not only the flowering of the Byzantine renaissance but also the seeds of its destruction.

Basil I 867–886

Non-dynastic years 1056–1059

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (February 2013) |

Doukid dynasty and the disaster at Manzikert 1059–1071

Late Empire 11th–15th centuries

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (February 2013) |

Arab conquests and threats

See the main article Byzantine–Arab Wars.

Arab attacks throughout the empire reduced significantly the territory once held under Justinian.

The Crusades and their effects

See the main article The Crusades and the Byzantine Empire.

The four crusades that involved the Byzantines severely weakened their power, and led to a disunity that would never be restored with success.

Breakaway successor states and the fall

The newly forming states of the Turks gradually squeezed the empire so much that it was only a matter of time before Constantinople was taken in 1453.

References

- ^ Jenkins R. Byzantium The Imperial Centuries AD 610-1071 p. xi

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History vol. xiv pp. 83–85

- ^ Runciman. Byzantine civilization p. 38

- ^ Garland 1999

- ^ Kazhdan, Alexander, ed. (1991). Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6.

- ^ Evans. Age of Justinian pp. 211–213

- ^ Ure. Justinian and his Age pp. 102–120

- ^ Evans. The Emperor Justinian And The Byzantine Empire pp. 5-6

- ^ Giftopoulou Sofia. Diocese of Asiana (Byzantium), Encyclopaedia of the Hellenic World, Asia Minor

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History vol. xiv p. 66

- ^ Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium

- ^ Jenkins, Romilly (1966). Byzantium The Imperial centuries AD 610–1071. p. 56

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica: Leo III

- ^ L. Brubaker and J. Haldon, Byzantium in the Iconoclast Era, c. 680-850 Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- ^ Jenkins. Byzantium The Imperial Centuries AD 610-1071. p. 117

- ^ Jenkins (1966). Byzantium The Imperial centuries AD 610-1071. p. 128