Cajamarca

Cajamarca | |

|---|---|

|

Clockwise from top: Santa Catalina Church, Nuestra Señora de la Piedad Chuch, partial view of the city | |

| Country | Peru |

| Region | Cajamarca Region |

| Province | Cajamarca Province |

| Founded | circa 1450 by the Incas; Spanish settlement in 1532 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Manuel Becerra |

| Area | |

| • Total | 392.47 km2 (151.53 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 2,750 m (9,020 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Estimate (2015)[1] | 226,031 |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (PET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (PET) |

| Area code | 76 |

| Website | http://www.cajamarcaperu.com/ http://www.municaj.gob.pe/ |

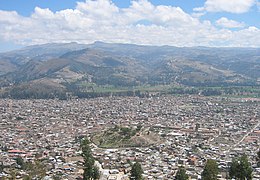

Cajamarca (Spanish pronunciation: [kaxaˈmaɾka]) is the capital and largest city of the Cajamarca Region as well as an important cultural and commercial center in the northern Andes. It is located in the northern highlands of Peru at approximately 2,750 m (8,900 ft) above sea level[2] in the valley of the Mashcon river.[3] Cajamarca has an estimated population for 2014 of about 218,775 inhabitants.[4]

Cajamarca has a mild highland climate, and the area has a very fertile soil. The city is well known for its dairy products and mining activity in the surroundings.[5][6]

Among its tourist attractions, Cajamarca has numerous examples of Spanish colonial religious architecture, beautiful landscapes, pre-Hispanic archeological sites and hot springs at the nearby town of Baños del Inca (Baths of the Inca). The history of the city is highlighted by the Battle of Cajamarca, which marked the defeat of the Inca Empire by Spanish invaders as the Incan emperor Atahualpa was captured and murdered here.

Etymology

The etymology of Cajamarca may mean 'town of thorns'[7] or 'cold place'[8] depending on the source. All sources agree that the word has quechua origin.[7][8]

History

The city and its surroundings have been occupied by several cultures for more than 2000 years. Traces of pre-Chavín cultures can be seen in nearby archaeological sites, such as Cumbe Mayo and Kuntur Wasi.

During the period between 1463 and 1471, Tupac Inca conquered the area and brought Cajamarca into the Tawantinsuyu, or Inca Empire. At the time, it was ruled by Tupac Inca's father Pachacuti.

In 1532 Atahualpa defeated his brother Huáscar in a battle for the Inca throne in Quito (in present-day Ecuador). On his way to Cusco to claim the throne with his army, he stopped at Cajamarca.[9]: 146–149

Francisco Pizarro (a 54-year old, experienced Indian killer, born in Extremadura, Spain]] and his 168 soldiers met Atahualpa here after weeks of marching from Piura. The Spanish Conquistadors and their Indian allies captured Atahualpa in the Battle of Cajamarca, where they also massacred several thousand unarmed Inca civilians and soldiers, out of a ceremonial army of 80,000, in an audacious surprise attack of cannon, cavalry, lances and swords. As the two leaders faced off, the young captain Hernando De Soto, rode on horseback directly up to Atahualpa to intimidate him.[10]

Having taken Atahualpa captive, they held him in Cajamarca's main temple. Atahualpa offered his captors a ransom for his freedom: a room filled with gold and silver (possibly the place now known as El Cuarto del Rescate or "The Ransom Room"), within two months. Although having complied with the offering, Atahualpa was brought to trial and executed by the Spaniards. Pizarro, De Soto, and others shared in the ransom.

In 1986 the Organization of American States designated Cajamarca as a site of Historical and Cultural Heritage of the Americas.[11]

Geography

Cajamarca is situated at 2750 m (8900 ft) above sea level on an inter-Andean valley irrigated by three main rivers: Mashcon, San Lucas and Chonta; the former two join together in this area to form the Cajamarca river.[12]

Cityscape

Architecture

The style of ecclesiastical architecture in the city differs from other Peruvian cities due to the geographic and climatic conditions. Cajamarca is further north with a milder climate; the colonial builders used available stone rather than the clay of used in the coastal desert cities.

Cajamarca has six Christian churches of Spanish colonial style: San Jose, La Recoleta, La Immaculada Concepcion, San Antonio, the Cathedral and El Belen. Although all were built in the seventeenth century, the latter three are the most outstanding due to their sculpted facades and ornamentation.

The facades of these three churches were left unfinished, most likely due to lack of funds. The façade of the Cathedral is the most elegantly decorated, to the extent that it was completed. El Belen has a completed façade of the main building, but the tower is half finished. The San Antonio church was left mostly incomplete.[13][14]

Church of Belen

This church consists of a single nave with no lateral chapels. Its facade is the most complete of the three, as it was the first to be designed and built.[13][14]

Cathedral of Cajamarca

Originally designated to be a parish church, the cathedral took 80 years to construct (1682–1762); the façade remains unfinished. The Cathedral shows how colonial Spanish influence was introduced in the Incan territory.

Side Portals: The side portals are made of pilasters on corbels. It also bears the royal escutcheon of Spain. The portal is considered to have a seventeenth-century character, found in the rectangular emphasis of the design.

Plan: The plan of the cathedral is based on a basilica plan, (with a single apse, barrel vaults in the nave, a transept and sanctuary), but the traditional dome over the crossing has been omitted.

Façade: The façade is noted for the detailing of its sculptures and the artistry in carving. Decorative details onclude grapevines carved into the spiral columns of the cathedral, with little birds pecking at the grapes. The frieze in the first story is composed of rectangular blocks carved with leaves. The detail of the main portal extends to flower pots and cherubs’ heads next to pomegranates. "The façade of Cajamarca Cathedral is one of the remarkable achievements of Latin American art."[13][14]

San Antonio

Construction began in 1699, with the original plans made by Matias Perez Palomino. This church is similar in plan to the Cathedral, but the interiors are quite different. San Antonio is a significantly larger structure and has incorporated the large dome over the crossing. Features of the church include large cruciform piers with Doric pilasters, a plain cornice, and stone carved window frames.

Façade: This façade is the most incomplete. While designed in a style similar to that of the cathedral, it is a simplified version.[13][14]

Climate

Cajamarca has a subtropical highland climate (Cwb, in the Köppen climate classification) which is characteristic of high elevations at tropical latitudes. This city presents a semi-dry, temperate, semi-cold climate with presence of rainfall mostly on spring and summer (from October to March) with little or no rainfall the rest of the year.

| Climate data for Cajamarca | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 21.5 (70.7) |

21.1 (70.0) |

20.9 (69.6) |

21.3 (70.3) |

21.6 (70.9) |

21.4 (70.5) |

21.4 (70.5) |

21.8 (71.2) |

21.7 (71.1) |

21.6 (70.9) |

21.9 (71.4) |

22.0 (71.6) |

21.5 (70.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 6.9 (44.4) |

6.7 (44.1) |

6.9 (44.4) |

6.2 (43.2) |

4.5 (40.1) |

3.4 (38.1) |

3.1 (37.6) |

3.6 (38.5) |

5 (41) |

6.2 (43.2) |

5.7 (42.3) |

5.9 (42.6) |

5.3 (41.6) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 83.9 (3.30) |

96.4 (3.80) |

110.3 (4.34) |

80.3 (3.16) |

34.6 (1.36) |

7 (0.3) |

6.3 (0.25) |

11.3 (0.44) |

32.8 (1.29) |

81.9 (3.22) |

73.2 (2.88) |

72.6 (2.86) |

690.6 (27.2) |

| Source: World Meteorological Organization[15] | |||||||||||||

Daily average temperatures have a great variation, being pleasant during the day but cold during the night and dawn.[16] January is the warmest month, with an average maximum temperature of 72 °F (22 °C) and an average minimum of 45 °F (7 °C). The coldest months are June and July, both with an average maximum of 71 °F (21 °C) but with an average minimum of 38 °F (3 °C).[17] Frosts may occur but are less frequent and less intense than in the southern Peruvian Andes.[3]

Economy

Cajamarca is surrounded by a fertile valley, which makes this city an important center of trade of agricultural goods. Its most renowned industry is that of dairy products.[5][6] Yanacocha is an active gold mining site 45 km north of Cajamarca, which has boosted the economy of the city since the 1990s.[18][19]

Transportation

The only airport in Cajamarca is Armando Revoredo Airport located 3.26 km northeast of the main square. Cajamarca is connected to other northern Peruvian cities by bus transport companies.

The construction of a railway has been proposed to connect mining areas in the region to a harbor in the Pacific Ocean.[20]

Education

Cajamarca is home of one of the oldest high schools in Peru: San Ramon School, founded in 1831.[21] Some of the largest, most important schools in the city include Marcelino Champagnat School, Cristo Rey School, Santa Teresita School, and Juan XXIII School.

Cajamarca is also a centre of higher education in the northern Peruvian Andes. The city hosts two local universities: Universidad Nacional de Cajamarca (National University of Cajamarca), a public university, while Universidad Antonio Guillermo Urrelo is a private one.[22] Five other universities have branches in Cajamarca: Universidad Antenor Orrego,[23] Universidad San Pedro,[24] Universidad Alas Peruanas,[25] Universidad Los Angeles de Chimbote[26] and Universidad Privada del Norte.[27]

Culture

Cajamarca is home to the annual celebration of Carnaval, a time when the locals celebrate Carnival before the beginning of Lent. Carnival celebrations are full of parades, autochthonous dances and other cultural activities. A local Carnival custom is to spill water and/or some paint among friends or bypassers. During late January and early February this turns in to an all-out water war between men and women (mostly between the ages of 6 and 25) who use buckets of water and water balloons to douse members of the opposite sex. Stores everywhere carry packs of water balloons during this time, and it is common to see wet spots on the pavement and groups of young people on the streets looking for "targets".

See also

References

- ^ Perú: Población estimada al 30 de junio y tasa de crecimiento de las ciudades capitales, por departamento, 2011 y 2015. Perú: Estimaciones y proyecciones de población total por sexo de las principales ciudades, 2012-2015 (Report). Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. March 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- ^ http://www.municaj.gob.pe/_geograf.php

- ^ a b Tourist Climate Guide. Available at: http://www.senamhi.gob.pe/?p=0160:: SENAMHI. 2008. p. 55.

{{cite book}}: External link in|location= - ^ http://proyectos.inei.gob.pe/web/biblioineipub/bancopub/Est/Lib1020/Libro.pdf

- ^ a b "Mantecoso Cheese in Peru". Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ^ a b "Cajamarca, Peru". Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ^ a b Sarmiento, Julio; Ravines, Tristán (1993). Cajamarca: Historia y Cultura. Instituto Andino de Artes Populares.

- ^ a b "Reseña Histórica". Municipalidad Provincial de Cajamarca. Retrieved September 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Prescott, W.H., 2011, The History of the Conquest of Peru, Digireads.com Publishing, ISBN 9781420941142

- ^ Davidson, James West. After the Fact: The Art of Historical Detection Volume 1. Mc Graw Hill, New York 2010, Chapter 1, p. 6

- ^ "Proceedings Volume I" (PDF). Organization of American States - General Assembly. 17 December 1986. p. 19. Retrieved 16 December 2015. (Ag/Res. 810 (XVI-0/86))

- ^ "Datos Generales". CajamarcaPeru.com. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ^ a b c d Harold E. Wethey, Colonial Architecture and Sculpture in Peru (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1949), 129-139

- ^ a b c d Damian Bayon and Murillo Marx, History of South American Colonial Art and Architecture (New York: Rizzoli Publications, 1992)

- ^ "World Weather Information Service (World Meteorological Organization)". Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- ^ Tourist Climate Guide. Available at: http://www.senamhi.gob.pe/?p=0160: SENAMHI. 2008. p. 57.

{{cite book}}: External link in|location= - ^ "World Weather Information Service". World Weather Information Service. World Weather Organization. Retrieved September 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ http://www.yanacocha.com.pe/quienes-somos/

- ^ http://www.yanacocha.com.pe/cifras/

- ^ "FERROCARRIL NORANDINA RAILROAD STARTS ITS JOURNEY COMING FEBRUARY". Minerandina.com. 10 January 2011. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- ^ http://www.panoramacajamarquino.com/noticia/colegio-central-de-artes-y-ciencias-de-cajamarca-san-ramon-1831/

- ^ http://www.upagu.edu.pe/

- ^ http://www.upao.edu.pe

- ^ http://www.usanpedro.edu.pe/historia/

- ^ http://www.uap.edu.pe/Esp/DondeEstamos/FilialesUAP/Cajamarca/Index.aspx

- ^ http://www.uladech.edu.pe/index.php/uladech-catolica/universidad/directorio-institucional/225-centros-uladech

- ^ http://www.upn.edu.pe/conocenos/nuestras-sedes

Further reading

- Conquest of the Incas. John Hemming, 1973.

External links

Cajamarca travel guide from Wikivoyage

Cajamarca travel guide from Wikivoyage- Cajamarca map

- Cajamarca information, photos and travel

- Miracle Village International a charity that works in Cajamarca with

- Villa Milagro

- Davy College

- MSN Map