1911 Canadian federal election

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

221 seats in the 12th Canadian Parliament 111 seats needed for a majority | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Canadian federal election of 1911 was held on September 21 to elect members of the Canadian House of Commons of the 12th Parliament of Canada. The central issue was Liberal support for a proposed treaty with the U.S. that would have lowered tariffs. The Conservatives denounced it because it threatened to weaken ties with Britain and submerge the Canadian economy—and Canadian identity—into its big neighbour. The Conservatives won and Robert Borden became prime minister. The idea of a Canadian Navy was also an issue. The election ended 15 years of government by the Liberal Party of Wilfrid Laurier.

Navy

The Liberal government was caught up in a debate over the naval arms race between the British Empire and Germany. Laurier attempted a compromise by starting up the Canadian Navy (now the Royal Canadian Navy), but this failed to appease either the French or English Canadians; the former who refused giving any aid, while the latter suggested sending money directly to Britain. After the election, the Conservatives drew up a bill for naval contributions to the British, but it was held up by a lengthy Liberal filibuster before being passed by invoking closure, then it was struck down by the Liberal-controlled Senate.

Ties to Britain

Many English Canadians in Alberta and the Maritimes felt that Laurier was abandoning Canada's traditional links to their mother country, Great Britain. On the other side, Quebec nationalist Henri Bourassa, having earlier quit the Liberal Party over what he considered the government's pro-British policies, campaigned against Laurier in that province. Ironically, Bourassa's attacks on Laurier in Quebec aided in the election of the Conservatives, who held more staunchly Imperialist policies than the Liberals. In mid-1910, Laurier had attempted to kill the Naval issue which was settling Anglo-Canadians against French-Canadians by opening talks for a reciprocity treaty with the United States, believing that an economically favorable treaty would appeal to most Canadians and have the additional benefit of dividing the Conservatives between the western wing of the party, which had long wanted free trade with the United States against the eastern wing, which were more opposed to Continentalism.[1] In January 1911, Laurier and President William Howard Taft of the United States announced that they signed an reciprocity agreement, which they decided to pass by concurrent legislation rather than a formal treaty as would normally been the case.[2] As such, the reciprocity agreement had to be ratified by both houses of Congress rather just the Senate, something that Laurier would come to regret.

Ties to the U.S.: Reciprocity

The base of Liberal support shifted to Western Canada. The West, seeking markets for its agricultural products, had long been a proponent of free trade with the United States.[3] The protected manufacturing businesses of Central Canada were strongly against it. The Liberals, who by ideology and history were strongly in favour of free trade, decided to make the issue the central plank of their re-election strategy, and negotiated a free trade agreement in natural products with the United States.

Allen argues that two speeches by American politicians gave the Conservatives the ammunition they needed to arouse anti-American, pro-British sentiments that provided the winning votes. The Democratic Speaker of the American House of Representatives Champ Clark declared on the floor of the House that: "I look forward to the time when the American flag will fly over every square foot of British North America up to the North Pole. The people of Canada are of our blood and language".[4] Clark went on to suggest in his speech that reciprocity agreement was the first step towards the end of Canada, a speech that was greeted with "prolonged applause" according to the Congressional Record.[5] The Washington Post reported that: "Evidently, then, the Democrats generally approved of Mr. Clark's annexation sentiments and voted for the reciprocity bill because, among other things, it improves the prospect of annexation".[6] The Chicago Tribunal in an editorial condemned Clark, warned that Clark's speech might had fatally damaged the reciprocity agreement in Canada and stated: "He lets his imagination run wild like a Missouri mule on a rampage. Remarks about the absorption of one country by another grate harshly on the ears of the smaller".[7]

Then Republican Congressman William Bennett of New York, a member of the House Foreign Relations Committee introduced a resolution asking the Taft administration to begin talks with Britain on how the United States might best annex Canada. Taft rejected the proposal, and asked the committee to take a vote on the resolution (which only Bennett voted for), but the Conservatives now had more ammunition.[8] Since Bennett, a strong protectionist, had been an opponent of the reciprocity agreement, the Canadian historian Chantal Allen suggested that Bennett had introduced his resolution with the aim of inflaming Canadian opinion against the reciprocity agreement.[9] Clark's speech that provoked massive outrage in Canada, and was taken by many Canadians as confirming the Conservative charge that the reciprocity agreement would result in American annexation of Canada.[10] The Washington Post noted that the effect of Clark's speech and Bennett's resolution in Canada had "roused the opponents of reciprocity in and out of Parliament to the highest pitch of excitement they have yet reached".[11] The Montreal Daily Star, English Canada's most widely read newspaper which until then had supported the Liberals and reciprocity now did a volte-face and turned against the reciprocity agreement. In an editorial, the Star wrote: "None of us realized the inward meaning of the shrewdly framed offer of the long headed American government when we first saw it. It was as cunning a trap as ever laid. The master bargainers of Washington have not lost their skill".[12] Contemporary accounts mentioned in the aftermath of Clark's speech that anti-Americanism was at an all-time high in Canada.[13] Many American newspapers advised their readers if they visited Canada not to identify themselves as American, lest they become the objects of abuse and hatred from the Canadians.[14] The New York Times in a July 1911 report stated that Laurier was "having the fight of his career to carry reciprocity at all".[15] One Conservative M.P. compared the relationship of Finance Minister William Stevens Fielding and President Taft to Samson and Delilah with Fielding having "succumbed to the Presidential blandishments".[16]

When the reciprocity agreement was submitted by Laurier to the House of Commons for ratification by Parliament, the Conservatives waged a vigorous filibuster against the reciprocity agreement on the floor of the House.[17] Although the Liberals still had two years left in their mandate, they decided to call an election to settle the issue after it aroused controversy and after Laurier was unable to break the filibuster.[18] Borden largely ran on a platform of opposing the reciprocity agreement under the grounds that it would "Americanize" Canada, and claimed that there was a secret plan on the part of the Taft administration to annex Canada with the reciprocity agreement being only the first step.[19] In his first speech given in London, Borden declared that: "It is beyond doubt that the leading public men of the United States, its leading press, and the mass of its people believe annexation of the Dominion to be the ultimate, inevitable, and desirable result of this proposition, and for that reason support it".[20] To support his claims, the Conservatives produced thousands of pamphlets reproducing the speeches of Clark and Bennett, which helped to fan the flames of a massive burst of anti-Americanism that was sweeping across English Canada in 1911.[21] One American newspaper wrote that the Conservatives were portraying the Americans as "a corrupt, bragging, boodle-hunting and negro lynching crowd from which Canadian workingmen and the Canadian land of milk and honey must be saved".[22] On 7 September 1911, the Montreal Star published a front-page appeal to all Canadians by the popular British poet Rudyard Kipling, who had been asked by his friend Max Aitken to write something for the Conservatives.[23] Kipling wrote in his appeal to Canadians that: "It is her own soul that Canada risks today. Once that soul is pawned for any consideration, Canada must inevitably conform to the commercial, legal, financial, social and ethical standards which will be imposed on her by the sheer admitted weight of the United States."[24] Kipling's appeal attracted much media attention in English Canada, and was reprinted over the next week in every English newspaper in Canada.[25]

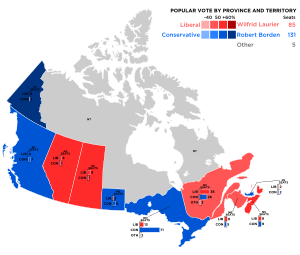

Results

The campaign went badly for the Liberals, however. The powerful manufacturing interests of Toronto and Montreal switched their allegiance and financing to the Conservatives. The Tories argued that free trade would undermine Canadian sovereignty and lead to a slow annexation of Canada by the U.S. In an editorial after Borden's victory, the Los Angeles Times wrote: "Their ballots have consigned to everlasting flames the bogy of annexation by the United States which Champ Clark called from the deeps. It was not really a wraith of anything that existed on this side of the line. It was a pumpkin scarehead with blazing eyes, a crooked slit for a nose, and a hideous grinning mouth which the fun-loving Champ placed upon a pole along with the Stars and Stripes, the while he carried terror to loyal Canuck hearts by his derisive shout of annexation".[26]

The election is often compared to the 1988 federal election, which was also fought over free trade. Ironically, in that later election, the positions of the two parties were reversed: the Liberals fought against the Tories' free trade proposal.

Voter turn-out: 70.2%

National results

| ↓ | ||||

| 132 | 85 | 4 | ||

| Conservative | Liberal | O | ||

| Party | Party leader | # of candidates |

Seats | Popular vote | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1908 | Elected | Change | # | % | Change

Template:Canadian politics/party colours/Progressive Conservatives/row |

Conservative 1 | Robert Borden | 208 | 82 | 131 | +59.8% | 625,697 | 48.03% | +3.08pp

Template:Canadian politics/party colours/Progressive Conservatives/row |

Liberal-Conservative | 2 | 3 | 1 | -66.7% | 6,842 | 0.53% | -0.74pp | Liberal 2 | Wilfrid Laurier | 214 | 133 | 85 | -36.1% | 596,871 | 45.82% | -3.05pp | Independent Conservative | 3 | - | 3 | 12,499 | 0.96% | +0.50pp | ||

| Labour | 3 | 1 | 1 | - | 12,101 | 0.93% | +0.04pp | Unknown | 10 | - | - | - | 25,857 | 1.98% | +0.83pp | Independent | 12 | 1 | - | -100% | 10,346 | 0.79% | -0.65pp | |||||||||||||||||

| Socialist | 6 | - | - | - | 4,574 | 0.35% | -0.17pp

Template:Canadian politics/party colours/Progressive Conservatives/row |

Nationalist Conservative 3 | 2 | * | - | * | 4,399 | 0.34% | * | Nationalist | 1 | * | - | * | 3,533 | 0.27% | * | |||||||||||||||||

| Total | 461 | 220 | 221 | +0.5% | 1,302,719 | 100% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sources: http://www.elections.ca -- History of Federal Ridings since 1867 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes:

* Party did not nominate candidates in the previous election.

1 One Conservative candidate was acclaimed in Ontario.

2 One Liberal candidate was acclaimed in Ontario, and two Liberals were acclaimed in Quebec.

Vote and seat summaries

Results by province

| Party name | BC | AB | SK | MB | ON | QC | NB | NS | PE | YK | Total

Template:Canadian politics/party colours/Progressive Conservatives/row |

Conservative | Seats: | 7 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 71 | 26 | 5 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 131

Template:Canadian politics/party colours/Progressive Conservatives/row |

Popular vote (%): | 58.7 | 38.5 | 39.0 | 51.9 | 53.5 | 44.1 | 43.6 | 44.5 | 51.1 | 60.8 | 48.0 | Liberal | Seats: | - | 6 | 9 | 2 | 13 | 36 | 8 | 9 | 2 | - | 85 | Vote (%): | 37.7 | 53.3 | 59.4 | 44.8 | 41.2 | 44.6 | 47.7 | 55.2 | 48.9 | 39.2 | 45.8 | Independent Conservative | Seats: | 1 | 2 | 3 | Vote (%): | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.0 | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Labour | Seats: | - | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vote (%): | 0.1 | 3.6 | 0.9

Template:Canadian politics/party colours/Progressive Conservatives/row |

Liberal-Conservative | Seats: | - | 1 | 1

Template:Canadian politics/party colours/Progressive Conservatives/row |

Vote (%): | 4.1 | 0.8 | 0.5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Total Seats | 7 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 86 | 65 | 13 | 18 | 4 | 1 | 221 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Parties that won no seats: | Unknown | Vote (%): | 1.0 | 2.1 | 2.6 | 8.7 | 2.0 | Independent | Vote (%): | 3.1 | 1.6 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 0.8 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Socialist | Vote (%): | 3.7 | 3.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.4

Template:Canadian politics/party colours/Progressive Conservatives/row |

Nationalist Conservative | Vote (%): | 0.3 | 1.0 | 0.3 | Nationalist | Vote (%): | 1.1 | 0.3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- List of Canadian federal general elections

- List of political parties in Canada

- 11th Canadian Parliament

References

- Argyle, Ray. Turning Points: The Campaigns That Changed Canada - 2011 and Before (2011) excerpt and text search, ch 5

- Brown, Robert Craig. Robert Laird Borden: A Biography (1975), the major scholarly biography

- Brown, Robert Craig, and Ramsay Cook. Canada: 1896-1921 (1974)

- Dafoe John W. Clifford Sifton in Relation to His Times. Toronto, 1931.

- Dafoe John W. Laurier: a Study in Canadian Politics. Toronto, 1922.

- Dutil, Patrice and David MacKenzie, Canada, 1911: The Decisive Election that Shaped a Country (2011)

- Ellis, L. Ethan. Reciprocity, 1911: A Study in Canadian-American Relations (1939) online

- Hopkins J. Castell (Comp.), The Canadian Annual Review of Public Affairs. Toronto, 1901- annual

- Johnston, Richard, and Michael B. Percy. "Reciprocity, Imperial Sentiment, and Party Politics in the 1911 Election," Canadian Journal of Political Science / Revue canadienne de science politique, Vol. 13, No. 4 (Dec., 1980), pp. 711–729 in JSTOR

- Neatby, H. Blair, Laurier and a Liberal Quebec: A Study in Political Management (1973) online

- Macquarrie, Heath. "Robert Borden and the Election of 1911." Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science, 1959, Vol. 25 Issue 3, pp 271–286 in JSTOR

- Porritt Edward. Sixty Years of Protection in Canada, 1846-1907: Where Industry Leans on the Politicians. (London, 1908) online

- Potter, Simon J. "The imperial significance of the Canadian-American reciprocity proposals of 1911." Historical Journal (2004) 47#1 pp: 81-100. abstract

- Stevens, Paul D. The 1911 General Election: A Study in Canadian Politics (Toronto: Copp Clard, 1970)

Primary sources

- Borden, Robert. Robert Laird Borden : his memoirs edited and with an introduction by Henry Borden

- Harpell James J., Canadian National Economy: the Cause of High Prices and Their Effect upon the Country. Toronto, 1911.

Notes

- ^ "1911 Federal Election in Canada". Mapleleafweb. Retrieved 2013-08-15.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "1911 Federal Election in Canada". Mapleleafweb. Retrieved 2013-08-15.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ MapleLeafWeb: 1911 Federal Election in Canada

- ^ Allan, Chantal Bomb Canada: And Other Unkind Remarks in the American Media Athabasca: Athabasca University Press, 2009 page 17.

- ^ Allan, Bomb Canada: And Other Unkind Remarks in the American Media page 18.

- ^ Allan, Bomb Canada: And Other Unkind Remarks in the American Media page 18.

- ^ Allan, Bomb Canada: And Other Unkind Remarks in the American Media page 18.

- ^ Allan, Chantal Bomb Canada: And Other Unkind Remarks in the American Media Athabsca: Athabasca University Press, 2009 page 18.

- ^ Allan, Chantal Bomb Canada: And Other Unkind Remarks in the American Media Athabsca: Athabasca University Press, 2009 page 18.

- ^ Allan, Chantal Bomb Canada: And Other Unkind Remarks in the American Media Athabsca: Athabasca University Press, 2009 page 18.

- ^ Allan, Chantal Bomb Canada: And Other Unkind Remarks in the American Media Athabsca: Athabasca University Press, 2009 pages 18-19.

- ^ Allan, Chantal Bomb Canada: And Other Unkind Remarks in the American Media Athabsca: Athabasca University Press, 2009 page 19.

- ^ Allan, Chantal Bomb Canada: And Other Unkind Remarks in the American Media Athabsca: Athabasca University Press, 2009 page 19.

- ^ Allan, Chantal Bomb Canada: And Other Unkind Remarks in the American Media Athabsca: Athabasca University Press, 2009 page 19.

- ^ Allan, Chantal Bomb Canada: And Other Unkind Remarks in the American Media Athabsca: Athabasca University Press, 2009 page 25.

- ^ Allan, Chantal Bomb Canada: And Other Unkind Remarks in the American Media Athabsca: Athabasca University Press, 2009 page 25.

- ^ Allan, Chantal Bomb Canada: And Other Unkind Remarks in the American Media Athabsca: Athabasca University Press, 2009 page 25.

- ^ Allan, Chantal Bomb Canada: And Other Unkind Remarks in the American Media Athabsca: Athabasca University Press, 2009 page 25.

- ^ Allan, Chantal Bomb Canada: And Other Unkind Remarks in the American Media Athabsca: Athabasca University Press, 2009 page 26.

- ^ Allan, Chantal Bomb Canada: And Other Unkind Remarks in the American Media Athabsca: Athabasca University Press, 2009 page 26.

- ^ Allan, Chantal Bomb Canada: And Other Unkind Remarks in the American Media Athabsca: Athabasca University Press, 2009 page 26.

- ^ Allan, Chantal Bomb Canada: And Other Unkind Remarks in the American Media Athabsca: Athabasca University Press, 2009 page 26.

- ^ MacKenzie, David & Dutil, Patrice Canada 1911: The Decisive Election that Shaped the Country, Toronto: Dundurn, 2011 page 211.

- ^ MacKenzie, David & Dutil, Patrice Canada 1911: The Decisive Election that Shaped the Country, Toronto: Dundurn, 2011 page 211.

- ^ MacKenzie, David & Dutil, Patrice Canada 1911: The Decisive Election that Shaped the Country, Toronto: Dundurn, 2011 page 211.

- ^ Allan, Chantal Bomb Canada: And Other Unkind Remarks in the American Media Athabsca: Athabasca University Press, 2009 page 29.