Centralia, Pennsylvania

Centralia, Pennsylvania

Bull's Head | |

|---|---|

Centralia as seen from South Street, July 2010 | |

Map showing Centralia in Columbia County | |

Map showing Columbia County in Pennsylvania | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Pennsylvania |

| County | Columbia |

| Settled | 1841 (as Bull's Head) |

| Incorporated | 1866 (Borough of Centralia) |

| Founded by | Jonathan Faust[1] |

| Government | |

| • Mayor a | Carl Womer (d.2014) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 0.24 sq mi (0.6 km2) |

| • Land | 0.24 sq mi (0.6 km2) |

| • Water | 0 sq mi (0 km2) 0% |

| Elevation | 1,467 ft (447 m) |

| Population (2010)[5] | |

| • Total | 10 |

| • Estimate (2013)[6] | 7 |

| • Density | 42/sq mi (16/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | |

| Area code | 570 |

| |

Centralia is a borough and a near-ghost town in Columbia County, Pennsylvania, United States. Its population has dwindled from over 1,000 residents in 1981 to only 10 in 2010[5] as a result of the coal mine fire that has been burning beneath the borough since 1962. Centralia, which is part of the Bloomsburg-Berwick micropolitan area, is the least-populated municipality in Pennsylvania and is completely surrounded by Conyngham Township.

All real estate in the borough was claimed under eminent domain and therein condemned by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in 1992 and Centralia's ZIP code was discontinued by the Postal Service in 2002.[7] State and local officials reached an agreement with the seven remaining residents on October 29, 2013, allowing them to live out their lives there, after which the rights of their houses will be taken through eminent domain.[6]

History

Early history

Many of the Native American tribes in what is now Columbia County sold the land that makes up Centralia to colonial agents in 1749 for the sum of five hundred pounds. In 1770, during the construction of the Reading Road, which stretched from Reading to Fort Augusta (present-day Sunbury), settlers surveyed and explored the land. A large portion of the Reading Road became what is now Route 61, the main highway east into and south out of Centralia.[8]

In 1793, Robert Morris, a hero of the Revolutionary War and a signatory of the Declaration of Independence, acquired a third of Centralia's valley land. When he declared bankruptcy in 1798, the land was surrendered to the Bank of the United States. A French sea captain named Stephen Girard purchased Morris' lands for $30,000, including 68 tracts east of Morris', because of the anthracite coal in the region.[8]

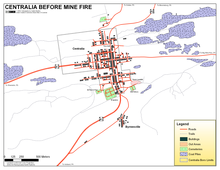

The Centralia coal deposits were largely overlooked before the construction of the Mine Run Railroad in 1854. In 1832, Johnathan Faust opened the Bull's Head Tavern in what was called Roaring Creek Township; this gave the town its first name, Bull's Head. In 1842, Centralia's land was bought by the Locust Mountain Coal and Iron Company, and Alexander Rae, a mining engineer, moved his family in and began planning a village, laying out streets and lots for development. Rae named the town Centreville, but in 1865 changed it to Centralia because the U.S. Post Office already had a Centreville in Schuylkill County. The Mine Run Railroad was built in 1854 to transport coal out of the valley.[1]

Mining begins

The first two mines in Centralia opened in 1856, the Locust Run Mine and the Coal Ridge Mine. Afterward came the Hazeldell Colliery Mine in 1860, the Centralia Mine in 1862, and the Continental Mine in 1863. The Continental was located on Stephen Girard's estate land. Branching from the Lehigh Valley Railroad, the Lehigh and Mahanoy Railroad came to Centralia in 1865 which expanded Centralia's coal sales to markets in eastern Pennsylvania.[8]

Centralia was incorporated as a borough in 1866. Its principal employer was the anthracite coal industry. Alexander Rae, the town's founder, was murdered in his buggy by members of the Molly Maguires on October 17, 1868, during a trip between Centralia and Mount Carmel.[9] Three men were eventually convicted of his death and were hanged in the county seat of Bloomsburg, on March 25, 1878. Several other murders and incidents of arson also took place during the violence, as Centralia was a hotbed of Molly Maguires activity during the 1860s. A legend among locals in Centralia tells that Father Daniel Ignatius McDermott, the first Roman Catholic priest to call Centralia home, cursed the land in retaliation for being assaulted by three members of the Maguires in 1869. McDermott said that there would be a day when St. Ignatius Roman Catholic Church would be the only structure remaining in Centralia. Many of the Molly Maguires' leaders were hanged in 1877, ending their crimes. Legends say that a number of descendants of the Molly Maguires still lived in Centralia up until the 1980s.[8]

According to numbers of Federal census records, the town of Centralia came to its maximum population of 2,761 in the year 1890. At its peak the town had seven churches, five hotels, twenty-seven saloons, two theaters, a bank, a post office, and 14 general and grocery stores. Thirty-seven years later the production of anthracite coal had reached its peak in Pennsylvania. In the following years production declined due to many young miners from Centralia enlisting in World War I. The year 1929 saw the crash of the stock market, which led to the Lehigh Valley Coal Company closing five of its Centralia-local mines. Bootleg miners still continued mining in several idle mines, using techniques such as what was called "pillar-robbing," where miners would extract coal from coal pillars left in mines to support their roofs. This caused the collapse of many idle mines, further complicating the prevention of the mine fire in 1962 when an effort was made to seal off the abandoned mines.

In the year 1950, Centralia Council acquired the rights to all anthracite coal beneath Centralia through a state law passed in 1949 that enabled the transaction. That year, the federal census counted 1,986 residents in Centralia.

Coal mining continued in Centralia until the 1960s, when most of the companies shut down. Bootleg mining continued until 1982 and strip and open-pit mining are still active in the area. There is an underground mine employing about 40 people three miles to the west.

Rail service ended in 1966. Centralia operated its own school district, including elementary schools and a high school. There were also two Catholic parochial schools. By 1980, it had just 1,012 residents. Another 500 or 600 lived nearby.[7]

Mine fire

Triggers

There is some disagreement over the specific event which triggered the fire. After studying available local and state government documents and interviewing former borough council members, David Dekok states in two works—Unseen Danger and its successor edition, Fire Underground: The Ongoing Tragedy of the Centralia Mine Fire—that in May 1962, the Centralia Borough Council hired five members of the volunteer fire company to clean up the town landfill, located in an abandoned strip-mine pit next to the Odd Fellows Cemetery just outside the borough limits. This had been done prior to Memorial Day in previous years, when the landfill was in a different location. On May 27, 1962, the firefighters, as they had in the past, set the dump on fire and let it burn for some time. Unlike in previous years, however, the fire was not fully extinguished. An unsealed opening in the pit allowed the fire to enter the labyrinth of abandoned coal mines beneath Centralia.[citation needed]

By contrast, Joan Quigley states in her 2007 book The Day the Earth Caved In that the fire had in fact started the previous day, when a trash hauler dumped hot ash or coal discarded from coal burners into the open trash pit. She noted that borough council minutes from June 4, 1962 referred to two fires at the dump, and that five firefighters had submitted bills for "fighting the fire at the landfill area". The borough, by law, was responsible for installing a fire-resistant clay barrier between each layer,[10] but fell behind schedule, leaving the barrier incomplete. This allowed the hot coals to penetrate the vein of coal underneath the pit and start the subsequent subterranean fire.[11][12]

According to another legend, the Bast Colliery coal fire of 1932 was never fully extinguished, and in 1962, it reached the landfill area.[8]

Immediate effects

In 1979, locals became aware of the scale of the problem when a gas-station owner, then-mayor John Coddington, inserted a dipstick into one of his underground tanks to check the fuel level. When he withdrew it, it seemed hot, so he lowered a thermometer into the tank on a string and was shocked to discover that the temperature of the gasoline in the tank was 172 °F (77.8 °C).[13] Statewide attention to the fire began to increase, culminating in 1981 when a 12-year-old resident named Todd Domboski fell into a sinkhole, 4 feet (1.2 m) wide by 150 feet (46 m) deep, that suddenly opened beneath his feet in a backyard. His cousin, 14-year-old Eric Wolfgang, pulled Domboski out of the hole and saved his life. The plume of hot steam billowing from the hole was tested and found to contain a lethal level of carbon monoxide.[14]

Although there was physical, visible evidence of the fire, residents of Centralia were bitterly divided over the question of whether or not the fire posed a direct threat to the town. In "The Real Disaster is Above Ground," Steve Kroll-Smith and Steve Couch identified at least six community groups, each organized around varying interpretation of the amount and kind of risk posed by the fire. In 1984, the Congress allocated more than $42 million for relocation efforts. Most of the residents accepted buyout offers and moved to the nearby communities of Mount Carmel and Ashland.[citation needed]

In 1992, Pennsylvania governor Bob Casey invoked eminent domain on all property in the borough, condemning all the buildings within. A subsequent legal effort by residents to overturn the action failed. In 2002, the U.S. Postal Service discontinued Centralia's ZIP code, 17927.[7][15] In 2009, Governor Ed Rendell began the formal eviction of the remaining Centralia residents.[16]

The Centralia mine fire extended beneath the village of Byrnesville, a short distance to the south, and caused it also to be abandoned.[17]

Condemnation and abandonment

Very few homes remain standing in Centralia. Most of the abandoned buildings have been demolished by the Columbia County Redevelopment Authority or reclaimed by nature. At a casual glance, the area now appears to be a field with many paved streets running through it. Some areas are being filled with new-growth forest. The remaining church in the borough, St. Mary's, holds weekly services on Sunday and has not yet been directly affected by the fire. The town's four cemeteries—including one on the hilltop that has smoke rising around and out of it—are maintained in good condition.[citation needed]

The only indications of the fire, which underlies some 400 acres (1.6 km2) spreading along four fronts, are low round metal steam vents in the south of the borough and several signs warning of underground fire, unstable ground, and carbon monoxide. Additional smoke and steam can be seen coming from an abandoned portion of Pennsylvania Route 61, the area just behind the hilltop cemetery, and other cracks in the ground scattered about the area. Route 61 was repaired several times until its final closing. The current route was formerly a detour around the damaged portion during the repairs and became a permanent route in 1993; mounds of dirt were placed at both ends of the former route, effectively blocking the road. Pedestrian traffic is still possible due to a small opening about two feet wide at the north side of the road. The underground fire is still burning and may continue to do so for 250 years.[14] The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania did not renew the relocation contract at the end of 2005.[18]

Prior to its demolition in September 2007, the last remaining house on Locust Avenue was notable for the five chimney-like support buttresses along each of two opposite sides of the house, where the house was supported by a row of adjacent buildings before it was demolished. Another house with similar buttresses was visible from the northern side of the cemetery, just north of the burning, partially subsumed hillside.[19]

John Comarnisky and John Lokitis, Jr. were evicted in May and July 2009, respectively. In May 2009, the remaining residents mounted another legal effort to reverse the 1992 eminent domain claim.[20] In 2010, only five homes remain as state officials try to vacate the remaining residents and demolish what is left of the town. In March 2011, a federal judge refused to issue an injunction that would have stopped the condemnation.[21] The Borough Council still has regular meetings as of 2011[update]. It was reported that the town's highest bill at the meeting reported on came from PPL, a power utility, at $92 and the town's budget was "in the black."[22]

In February 2012, the Commonwealth Court ruled that a declaration of taking could not be re-opened or set aside on the basis that the purpose for the condemnation no longer exists; seven people, including the Borough Council president, had filed suit claiming the condemnation was no longer needed because the underground fire had moved and the air quality in the borough was the same as that in Lancaster.[21] In October 2013, the remaining residents settled their lawsuit receiving $218,000 in compensation for the value of their homes along with $131,500 to settle additional claims, and the right to stay in their homes for the rest of their lives.[6][23]

Time capsule

The town's residents and former residents decided to open a time capsule buried in 1966 a few years earlier than planned after someone had attempted to unearth and steal the capsule in May 2014. The capsule was not scheduled to be opened until 2016. Instead, the capsule was unearthed in June 2014 by a group of former residents and the Centralia chapter of the American Legion on whose lawn it was buried. The capsule was officially opened a few months later during a public ceremony held on October 4, 2014 in Wilburtown, Pennsylvania. Items found in the footlocker-sized capsule—which had been inundated with about 12 inches (30 cm) of water—included a miner’s helmet, a miner’s lamp, some coal, a Bible, local souvenirs, and a pair of bloomers signed by the men of Centralia in 1966.[24][25]

Mineral rights

Several current and former Centralia residents believe the state's eminent domain claim was a plot to gain the mineral rights to the anthracite coal beneath the borough. Residents have asserted its value to be in the hundreds of millions of dollars, although the exact amount of coal is not known.[21][16][26][27] This theory stems from the municipality laws of the state. According to state law, when the municipality can no longer form a functioning municipal government, i.e., when there are no longer any residents, the borough legally ceases to exist.[citation needed] At that point, the mineral rights, which are owned by the Borough of Centralia (they are not privately held) would revert to the ownership of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.[citation needed]

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 1,342 | — | |

| 1880 | 1,886 | 40.5% | |

| 1890 | 2,761 | 46.4% | |

| 1900 | 2,048 | −25.8% | |

| 1910 | 2,429 | 18.6% | |

| 1920 | 2,336 | −3.8% | |

| 1930 | 2,446 | 4.7% | |

| 1940 | 2,449 | 0.1% | |

| 1950 | 1,986 | −18.9% | |

| 1960 | 1,435 | −27.7% | |

| 1970 | 1,165 | −18.8% | |

| 1980 | 1,017 | −12.7% | |

| 1990 | 63 | −93.8% | |

| 2000 | 21 | −66.7% | |

| 2010 | 10 | −52.4% | |

| 2013 (est.) | 7 | [6] | −30.0% |

| Sources:[28][29][30] | |||

2000 census

As of the census[31] of 2000, there were 21 people, 10 households, and 7 families residing in the borough. The population density was 87.5 people per square mile (3.38 km²). There were 16 housing units at an average density of 66.7 people per square mile (2.57 km²). The racial makeup of the borough was 100% white.

There were 10 households, out of which 1 (10%) had children under the age of 18 living with them, 5 (50%) were married couples living together, 1 had a female householder with no husband present, and 3 (30%) were non-families. 3 of the households were made up of individuals, and 1 had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.10, and the average family size was 2.57.

In the borough the population was spread out, with 1 resident under the age of 18, 1 from 18 to 24, 4 from 25 to 44, 7 from 45 to 64, and 8 who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 62 years. There were 10 females and 11 males with 1 male under the age of 18.

The median income for a household in the borough was $23,750, and the median income for a family was $28,750. The per capita income for the borough was $16,083. None of the population was below the poverty line.

2010 census

As of the census of 2010[32] there were 10 people (down 52% since 2000), 5 households (down 50%), and 3 families (down 57%) residing in the borough. The population density was 42 people per square mile (16/km²) (down 52%). There were 6 housing units (down 62.5%) at an average density of 0.4 units per square mile (.015 units/km²). The racial makeup of the borough was 100% white.[33]

Of the five households, none had children under the age of 18. Two (40%) were married couples living together, one (20%) had a female householder with no husband present, and two (40%) were non-families. One of those non-family households was an individual, and none had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.0 persons, and the average family size was 2.33 persons.[33]

There were no residents under the age of 18, one aged 25–29, one aged 50–54, one aged 55–59, four aged 60–64, two aged 70–74, and one aged 80–84. The median age was 62.5 years, and there were five females and five males in total.[33]

Public services

Though it originally fielded its own three-man department (one full-time chief and two part-time officers) during the latter part of the 20th century, Centralia Borough is now patrolled solely by the Pennsylvania State Police's Bloomsburg Station.[citation needed]

The borough is served by a small group of volunteer firefighters operating one firetruck that is more than 30 years old. The fire company's ambulance was given to the nearby Wilburton Fire Company in Conyngham Township in 2012. Life-long resident Thomas Hynoski is the fire chief.[citation needed]

Legacy

Every few years, a reporter will write a piece about the remaining residents of Centralia, wondering why they have not left. It has also been the subject of numerous non-fiction books and histories, including first-person accounts of exploration.[34]

Depictions of Hell

Centralia has been used as a model for many different ghost towns and physical manifestations of Hell. Prominent examples include Dean Koontz's Strange Highways and David Wellington's Vampire Zero.[34] Centralia was also an inspiration for the Silent Hill film adaptations.[35] and Nothing but Trouble.[36]

Popular culture

The 1987 film Made in U.S.A. directed by Ken Friedman and starring Adrian Pasdar, Chris Penn and Lori Singer opens in Centralia and the surrounding coal region of Pennsylvania.[37]

The 2007 documentary The Town That Was is about the history of the town and its current and former residents.[38]

Centralia had a segment entitled "City on Fire" on the Travel Channel television series America Declassified which aired in 2013.[39]

The Centralia story was explored in depth in the documentary segment "Dying Embers" from public radio station WNYC's RadioLab.[40]

See also

- Coal seam fires

- Brennender Berg (Saarland, Germany)

- Burning Mountain (New South Wales, Australia)

- Door to Hell (Derweze, Turkmenistan)

- Jharia (India)

- Smoking Hills (Northwest Territories, Canada)

- Times Beach, Missouri

References

- ^ a b DeKok, David (1986). Unseen Danger; A Tragedy of People, Government, and the Centralia Mine Fire. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-595-09270-3.

- ^ "Carl Womer, Centralia Pennsylvania's Last Mayor". Centralia PA. November 25, 2014. Retrieved December 14, 2015.

- ^ "Obituary of Carl T. Womer". Dean W. Kriner Funeral Home.

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Borough of Centralia

- ^ a b "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Census Summary File 1 (G001): Centralia borough, Pennsylvania". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Ratchford, Dan (October 30, 2013). "Agreement Reached With Remaing(sic) Centralia Residents". WNEP 16. Archived from the original on May 29, 2016. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Krajick, Kevin (May 2005). "Fire in the hole". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved July 27, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e DeKok, David. Fire Underground: The Ongoing Tragedy of the Centralia Mine Fire.

- ^ Willard Cilvik, "The Murder of Alexander W. Rea"

- ^ "Abandoned Mines in Pennsylvania". Maiello, Brungo & Maiello. Retrieved December 15, 2015.

- ^ Quigley, Joan (2007). The Day the Earth Caved In: An American Mining Tragedy. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-6180-8.

- ^ Quigley, Joan (2007). "Chapter Notes to The Day the Earth Caved In" (DOC). p. 8. Retrieved March 13, 2012.

- ^ Morton, Ella. "How an Underground Fire Destroyed an Entire Town". Slate. Retrieved August 2, 2014.

- ^ a b O'Carroll, Eoin. "Centralia, Pa.: How an underground coal fire erased a town". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved August 5, 2013.

- ^ Currie, Tyler (April 2, 2003). "Zip Code 00000". Washington Post. Retrieved December 19, 2009.

- ^ a b Rubinkam, Michael (February 5, 2010). "Few Remain as 1962 Pa. Coal Town Fire Still Burns". ABC News (Australia). Retrieved February 6, 2010.

- ^ Holmes, Kristin E. (October 21, 2008). "Minding a legacy of faith: In an empty town, a shrine still shines". Philly.com.

- ^ Reading Eagle, January 3, 2006

- ^ "A modern day Ghost Town, Centralia Pennsylvania". Retrieved October 10, 2007.

- ^ "Few remain as 1962 Pa. coal town fire still burns," Yahoo News, February 5, 2010

- ^ a b c Beauge, John (February 23, 2012). "Court denies Centralia property owners looking to keep their homes". The Patriot-News. Retrieved March 12, 2012.

The same individuals have a suit pending in U.S. Middle District Court that alleges the condemnation was part of the commonwealth's plot to obtain mineral rights to the anthracite coal they claim are worth hundreds of millions of dollars.

- ^ Wheary, Rob (February 13, 2011). "'Regular borough council' in Centralia". Pottsville Republican. Retrieved April 24, 2012.

- ^ Rubinkam, Michael (October 31, 2013). "Pa. residents living above mine fire free to stay". Associated Press. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved November 3, 2016 – via Yahoo Finance.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Centralia PA Time Capsule Opened Early". October 5, 2014. Retrieved March 14, 2016.

- ^ "Centralia Time Capsule to be Opened in 2016 [see Update: The Centennial Vault time capsule was opened in 2014]". September 5, 2014. Retrieved March 14, 2016.

- ^ This is stated in Joan Quigley's The Day the Earth Caved In in a section that indicated that Centralia is the only municipality within the Commonwealth that actually owned its mineral rights.

- ^ Walter, Greg (June 22, 1981). "A Town with a Hot Problem Decides Not to Move Mountains but to Move Itself". People. Retrieved December 25, 2008.

Despite the inferno below them and the gases that seep into their basements, some Centralians do not want to leave their homes and remain convinced that it's all a plot by coal companies to drive them off valuable land since the borough owns mineral rights to the coal below. (Other rumored villains have variously included anonymous Arabs and large energy cartels.)

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ^ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: Pennsylvania: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2013". Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- ^ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- ^ a b c "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010: 2010 Demographic Profile Data". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ a b Eby, Margaret. "American Inferno". Paris Review. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

- ^ Davidson, Paul. "Silent Hill Round Up". IGN. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

- ^ Dirks, Tim. "Greatest Box-Office Bombs, Disasters and Flops of All-Time". filmsite.org. AMC Networks. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

- ^ http://www.centraliapa.org/video-centralia-movie-made-usa/

- ^ http://www.snagfilms.com/films/title/the_town_that_was

- ^ "City on Fire". Travel Channel. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- ^ "Dying Embers". RadioLab. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

Notes

- a Upon his death, Womer became the last official mayor in the town.

Further reading

- DeKok, David. Unseen Danger: A Tragedy of People, Government, and the Centralia Mine Fire, University of Pennsylvania Press, ISBN 0-595-09270-5.

- Jacobs, Renee. Slow Burn: A Photodocument of Centralia, Pennsylvania, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1986, ISBN 0-8122-1235-5.

- Johnson, Deryl B. Images of America: Centralia, Arcadia Publishing, 2004, ISBN 978-0-7385-3629-3.

- Kroll-Smith, J. Stephen, and Couch, Stephen. The Real Disaster Is Above Ground: A Mine Fire and Social Conflict, University Press of Kentucky, January 1990, ISBN 0-8131-1667-8, ISBN 978-0-8131-1667-9.

- Moran, Mark. Weird U.S., Barnes & Noble, ISBN 0-7607-5043-2.

- Quigley, Joan. The Day the Earth Caved in: An American Mining Tragedy, Random House, 2007, ISBN 978-1-4000-6180-8.

- Inferno: The Centralia Mine Fire.

External links

- Fifty years of fire in the abandoned US town of Centralia, BBC News, August 8, 2012

- The Town That Was, a 70 minute SnagFilms.com video

- Bloomsburg–Berwick metropolitan area

- Boroughs in Columbia County, Pennsylvania

- Coal towns in Pennsylvania

- Ghost towns in Pennsylvania

- Environmental disasters in the United States

- Environmental disaster ghost towns

- Municipalities of the Anthracite Coal Region of Pennsylvania

- Populated places established in 1841

- Boroughs in Pennsylvania

- 1841 establishments in Pennsylvania

- Persistent natural fires

- Destroyed towns