Coast Guard Squadron One

| Coast Guard Squadron One | |

|---|---|

Coast Guard Squadron One patch | |

| Active | 27 May 1965 – 15 August 1970 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Nickname(s) | "RONONE"[1] |

| Engagements | Vietnam War |

| Decorations | Presidential Unit Citation (U.S. Navy)[2] Navy Unit Commendation[3] Meritorious Unit Commendation (Navy)[4] |

Coast Guard Squadron One, also known in official message traffic as COGARDRON ONE or RONONE, was a combat unit formed by the United States Coast Guard in 1965 for service during the Vietnam War. Placed under the operational control of the United States Navy, it was assigned duties in Operation Market Time. Its formation marked the first time since World War II that Coast Guard personnel were used extensively in a combat environment.

The squadron operated divisions in three separate areas during the period of 1965 to 1970. Twenty-six Template:Sclass-s with their crews and a squadron support staff were assigned to the U.S. Navy with the mission of interdicting the movement of arms and supplies from the South China Sea into South Vietnam by Viet Cong and North Vietnam junk and trawler operators. The squadron also provided naval gunfire support to nearby friendly units operating along the South Vietnamese coastline and assisted the U.S. Navy during Operation Sealords. As the United States' direct involvement in combat operations wound down during 1969, squadron crews began training Republic of Vietnam Navy (RVN) sailors in the operation and deployment of the cutters. The cutters were later turned over to the RVN as part of the Vietnamization of the war effort. Turnover of the cutters to South Vietnamese Navy crews began in May 1969 and was completed by August 1970. Squadron One was disestablished with the decommissioning of the last cutter.

The squadron was awarded several unit citations for its service to the U.S. Navy and the South Vietnamese government during the six years the unit was active with over 3,000 Coast Guardsmen serving aboard cutters and on the squadron support staff. Six squadron members were killed in action during the time the unit was commissioned.

Squadron One, along with American and South Vietnamese naval units assigned to the task force that assumed the Market Time mission, were successful interdicting seaborne North Vietnamese personnel and equipment from entering South Vietnamese waters. The success of the blockade served to change the dynamics of the Vietnam War, forcing the North Vietnamese to use a more costly and time-consuming route down the Ho Chi Minh trail to supply their forces in the south.

Background

As the United States military involvement in South Vietnam shifted from an advisory role to combat operations, advisors from Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV) to the South Vietnamese military noticed an increase in the amount of military supplies and weapons being smuggled into the country by way of North Vietnamese junks and other small craft.[8][9] The extent of infiltration was underscored in February 1965 when a U.S. Army helicopter crew spotted a North Vietnamese trawler camouflaged to look like an island.[10] The event would later be known as the Vung Ro Bay Incident, named for the small bay that was the trawler's destination.[11][12] After the U.S. Army helicopter crew called in air strikes on the trawler, it was sunk and captured after a five-day action conducted by elements of the Republic of Vietnam Navy (RVN). Investigators found one million rounds of small arms ammunition, more than 1,000 stick grenades, 500 pounds of prepared TNT charges, 2,000 rounds of 82 mm mortar ammunition, 500 anti-tank grenades, 1,500 rounds of recoilless rifle ammunition, 3,600 rifles and sub-machine guns, and 500 pounds of medical supplies.[12] Labels on captured equipment and supplies and other papers found in the wreckage indicated that the shipment was from North Vietnam. Concern by top MACV advisors as to whether the RVN was up to the task of interdicting shipments originating in North Vietnam led to a request by General William C. Westmoreland, commanding general of MACV, for U.S. Navy assistance.[13]

The request was initially filled by U.S. Navy radar picket destroyer escorts (DER) and minesweepers (MSO) in March when Operation Market Time was started, but these vessels had too great a draft to operate effectively in shallow coastal waters.[14] In April the U.S. Navy ordered 54 Swift boats (PCF), 50-foot (15 m) aluminum-hulled boats with a draft of only 5 feet (1.5 m) and capable of 25 knots (29 mph; 46 km/h). At the same time, the U.S. Navy queried the Treasury Department, the lead agency for the U.S. Coast Guard at the time, about the availability of suitable vessels.[15][16] The Coast Guard had only a very minor role in combat operations during the Korean War and the Commandant of the Coast Guard, Admiral Edwin J. Roland, responded to the request by offering the use of 82-foot (25 m) Point-class cutters (WPB) and 40-foot (12 m) utility boats, fearing that, if the Coast Guard were left out of a role in Vietnam, its status as one of the nation's armed services might be jeopardized.[14]

The decision to use the Point-class cutter was one of logistics. The 95-foot (29 m) Cape-class cutter was initially considered an option by Roland since it had a greater speed because of its four main drive engines. The Point-class cutter had only two main drive engines but they were more consistent throughout the class than the Cape-class cutters, so it was easier to supply spare parts and maintain the engines.[17] Additional factors favoring the Point-class cutter were an unmanned engine room with all controls and alarms on the bridge, and air-conditioned living spaces, a big factor in a tropical climate where crews were expected to live on the boat whether on or off duty.[18] The 40-foot utility boats were rejected because they lacked radar, berthing, and mess facilities for extended patrols offshore.[17]

On 22 April representatives of the U.S. Coast Guard and the U.S. Navy signed a memorandum of understanding stating that the Coast Guard would supply 17 Point-class cutters and their crews and the Navy would provide transport to South Vietnam and logistical support with two tank landing ships (LST) that had been converted to repair ships.[14][19] Ten of the cutters were sourced from stations on the Atlantic and Gulf coasts and seven were sourced from Pacific coast stations. After removal of the Oerlikon 20–mm cannon on the bow, in place of which each cutter was fitted with a combination mount consisting of a 81 mm mortar which could be either drop-fired or trigger-fired, above which was mounted a .50 caliber M2 Browning machine gun. The mortar could be fired in both indirect and direct modes, and was equipped with a recoil cylinder.[20][Note 2] The cutters were loaded on merchant ships for shipment to U.S. Naval Base Subic Bay in the Philippines.[21] On 29 April President Lyndon B. Johnson authorized Coast Guard units to operate under Navy command in Vietnam and to provide surveillance and interdiction assistance to U.S. Navy vessels and aircraft in an effort to stop the infiltration of troops, weapons and ammunition into South Vietnam by North Vietnamese Army (NVA) and Viet Cong (VC) forces.[22]

Crew training and unit commissioning

While the cutters were being shipped to Subic Bay, crew members started reporting to Coast Guard Training Center Alameda, California on 17 May 1965 for overseas processing and training.[23] The cutter crews received one week of small arms training at Naval Amphibious Base Coronado and Camp Pendleton while Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape (SERE) training was received at Marine Corps Mountain Warfare Training Center, near Coleville, California, in the Sierra Nevada Mountains and at Whidbey Island Naval Air Station, Washington.[24] Returning to Alameda, they underwent refresher firefighting and damage control training from the Navy at Treasure Island Naval Base. Additional weapons qualifications and live fire exercises were held at Coast Guard Island and Camp Parks, California, along with refresher training in radar navigation, radio procedures and visual signaling. Gun crews received mortar and machine gun training at Camp Pendleton.[24] Of the 245 personnel assigned to the unit only 131 were present at the squadron commissioning ceremony held at Alameda on 27 May with the remainder of the crews in the process of completing training elsewhere.[21][23] For service in Vietnam, two officers were added to the normal crew complement of eight to add seniority to the crew in the mission of interdicting vessels at sea. All officers assigned to command cutters were required to be lieutenants and to have previously commanded a Cape-class cutter and had to volunteer for the assignment. The executive officer was either a lieutenant junior grade or ensign.[25]

Naval Base Subic Bay

Divisions 11 and 12

The first crews arrived at Subic Bay on 11 June and a squadron office was established. On 12 June 1965, the squadron came under the operational control of the commander, Vietnam Patrol Force (CTF 71). Administrative control for personnel actions such as pay and personnel records was retained by the Coast Guard.[26] The first cutters arrived at Subic Bay on 17 June and before they were put in the water each hull bottom was inspected, repaired if necessary and painted from the waterline down. Mechanical, ordnance, electrical and electronic maintenance checks were completed before any modifications for duty in Vietnam were attempted. Modifications completed at Subic Bay included new radio transceivers, fabrication of gunner's platforms and ammunition ready boxes for the mortar, the addition of floodlights for night boardings, installation of small arms lockers on the mess deck and addition of sound-powered telephone circuits.[26] Additional bunks and refrigerators were added to increase patrol on-station time.[27] Modifications were made to the bow-mounted over-under machine gun mortar combination allowing it to be depressed below the horizon for close-range firing. Four additional M-2 machine guns with ready boxes were added to the gunwales of each cutter.[26]

As the crews arrived from the United States, they began doing required modification work in the shipyard and shakedown sorties in an effort to get all systems working. Night training exercises and gunnery drills were held each day and underway drills and training had been completed and commissary stores loaded by 9 July.[28] A one-day survival training course was conducted by Negrito natives and completion was compulsory for all squadron personnel.[28] When it became known that the cutters would be operating in two widely separated locations, Squadron One was divided into two divisions with Division 11 operating in the Gulf of Thailand at An Thoi, Phu Quoc Island[5] and Division 12 operating near the port of Da Nang[6] close to the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ).[26][29] Division 11 consisted of nine cutters and Division 12 consisted of eight cutters. At 16:00 on 16 July, Division 12 got underway and once out of the harbor they formed up on USS Snohomish County, the LST permanently assigned to support the division at Da Nang. Division 11 and USS Floyd County, the division's LST support ship, left Subic Bay bound for Phu Quoc Island at 08:00 on 24 July[28]

Division 13

After reviewing a study of the overall infiltration threat, MACV requested additional aircraft and patrol vessels for Operation Market Time. A request for an additional division of Point-class cutters to be added to Squadron One was made on 5 August 1965 and preparations for deploying the additional cutters started in late October with the new division of nine patrol boats to be named Division 13.[30] The staff and repair personnel arrived at Subic Bay 14 December 1965 while the division's boat crews received weapons and undertook survival training in California. The crews started arriving at Subic Bay on 28 December where additional survival and weapons training was given.[31] Twenty-one of the division's personnel were sent to Divisions 11 and 12 to be exchanged for crewmen who had Market Time experience.[31] Division 13 cutters began arriving as deck cargo on transport ships at Subic Bay on 24 January 1966 and crews commenced outfitting and painting them deck gray. Some of the outfitting had been accomplished before shipment so that more time could be devoted to training crews in gunnery and procedure before the division's scheduled departure for Vietnam on 18 February.[31] During a training exercise on 13 February, the main engine alarm sounded on the bridge of Point League. After checking the cause of the alarm, it was determined that a complete overhaul of one of the engines would be required. Division 12 shipped a complete kit of repair parts from Da Nang overnight by way of a U.S. Marine Corps C-130 flight to Cubi Point Naval Air Station. The flight was met by division personnel and repairs commenced. Divided into three shifts, the crews worked around-the-clock and the repairs were completed in 72 hours.[32] A partial load break-in was made the morning of departure and the rest of the procedure was completed while the division was en route to Vietnam.[33] At 16:00 on 18 February, Division 13 left Subic Bay in the company of USS Forster, arriving at the RVN Base at Cat Lo on 22 February.[7][34] Patrol work for six of the division's cutters began at 08:00 the following morning, covering the area from 60 miles (97 km) north of Vung Tau to 120 miles (193 km) south.[35]

Operations

Arrival in South Vietnam

Division 12 arrived at the port city of Da Nang at 07:00 on 20 July 1965 and was the first U.S. Coast Guard unit to be stationed in South Vietnam.[36] The morning after their arrival five of the division's eight cutters prepared to get underway for their first patrol accompanied by the Navy destroyer USS Savage, which coordinated the Market Time assets in the Da Nang area.[37]

Division 11 arrived at Con Son Island[38] on 29 July taking shelter from heavy seas and monsoon rains that had developed during the transit. Point Banks was the only cutter to have engine problems during the transit and repairs were made in the cramped engine room while underway so that no time was lost by the division during transit. During the lay over at Con Son minor repairs were made and repainting was completed on some of the cutters' hulls which had been partially stripped of paint by the storm. Three RVN liaison officers reported aboard the cutters just before the division departed for Phu Quoc Island and the same three cutters started patrol work as the rest of the division put into Phu Quoc harbor on 31 July.[39] On 30 July operational control of all Market Time elements, whether U.S. Navy, U.S. Coast Guard or RVN, was transferred to the Commander, Task Force 115 (TF115).[40]

Market Time operational theory

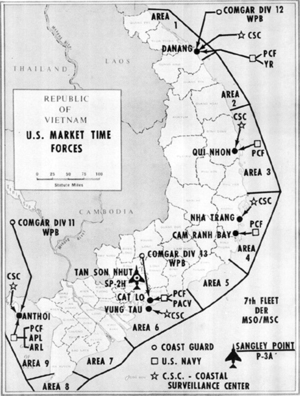

Market Time planners sectioned off nine patrol areas numbered in order from the DMZ in the north to the Cambodian border in the south. The areas varied in size, measuring 80 by 120 miles (130 km × 190 km) wide and running 30 to 40 miles (48 to 64 km) out to sea. The outer two-thirds of each area was covered by the U.S. Navy DER and MSO fleet and was identified by the area number with the suffix "B". After May 1967 high endurance cutters (WHEC) from Coast Guard Squadron Three also assisted in the outer patrol areas.[41] Because the inner third of each patrol area was usually shallow water it was covered by Navy PCFs and Coast Guard WPBs which had shallow drafts. These smaller patrol areas were identified by a letter "C" or higher. Thus, the patrol area covering the waters near Cam Ranh Bay[42] would have the outer two-thirds designated "4B" and the waters nearer shore designated "4C" through "4H".[43] Overflying the whole area were Navy patrol aircraft that flew various assigned tracks, reporting any traffic to watchstanders stationed at five Coastal Surveillance Centers (CSC) operated jointly by the U.S. Navy and RVN. Reports of movements by suspicious vessels were relayed to the nearest Market Time patrol craft whose duty it was to board and search for contraband material and persons on board without proper identification.[44] The rules of engagement that Market Time forces operated under allowed any vessel except warships to be stopped, boarded and searched within three miles (4.8 km) of the coastline and from the area three miles to twelve miles (19.4 km) from shore, identification and a declaration of intent could be demanded of any vessel except a warship. Outside the twelve-mile limit only vessels of South Vietnamese origin could be stopped, boarded and searched.[45][46]

While on patrol the cutters operated under orders from an operational commander at the CSC and not the division commander to which they were assigned.[47][48] The division was responsible for seeing that each cutter was ready to perform her assignments and properly supplied with trained personnel, supplies and equipment.[47] Each division's staff performed regular readiness reviews on each assigned cutter; riding with the crews to judge their effectiveness.[48]

On 30 September 1968, Vice Admiral Elmo Zumwalt assumed command of Naval Forces Vietnam and he redirected the focus of interdiction operations conducted by TF115 to areas nearer the DMZ as a part of Operation Sealords (Southeast Asia Lake, Ocean, River, and Delta Strategy). The result was that all but four Division 11 WPBs were transferred to Divisions 12 and 13 and the shallower draft U.S. Navy PCFs that had been used for patrol duties at the DMZ were used to patrol the canals and rivers.[49]

Major cutter operations

1965

Soon after patrol operations started in Division 12's area of responsibility (AOR), Point Orient encountered machine gun and mortar fire from the shore south of the Cua Viet River while attempting to board a junk in the early morning hours of 24 July 1965. The Point Orient returned fire, and in doing so it became the first Coast Guard unit in Vietnam to engage the enemy.[50] As a result of the incident, it became obvious to the skipper of the Point Orient that the paint scheme used by the Coast Guard in the U.S. was too visible at night and shortly thereafter the white paint was replaced by deck gray on all WPBs in Squadron One.[40] On assuming control, the TF115 commander changed the way patrols were conducted in the DMZ. Future patrols were concentrated along the DMZ for most of the WPBs and PCFs with only a few assets placed in the Da Nang area. Assets were concentrated where vessel traffic was encountered; most traffic near the Da Nang area was interdicted further out to sea by the DERs and WHECs and fewer shallow draft assets were needed there.[50][51]

19 September was a busy day for Division 11 in the Gulf of Thailand with Point Glover encountering a junk that fired on her and when unable to escape tried to ram the cutter. The Viet Cong crew jumped overboard and Point Glover disabled the junk's engine with machine gun fire. A boarding party from Point Glover boarded the sinking junk and did a quick search of the vessel, finding arms and ammunition. Unable to stop the junk from sinking, she was beached in shallow water while Point Garnet,Point Clear and Point Marone went searching for the missing junk crew; however, only one crew member was captured.[52] Later that night Point Marone attempted to stop an unlit junk near the coastal town of Ha Tien[53] but the junk ignored a warning shot across her bow and attempted to evade boarding while firing at the cutter and throwing hand grenades. Point Glover was nearby and assisted Point Marone in engaging the junk with machine gun fire. The junk caught fire and started sinking. Unable to keep the junk afloat the cutter crews marked it with a buoy and let it sink in shallow water. Salvage operations conducted later found rifles, ammunition, hand grenades, documents and money.[54] Eleven Viet Cong were killed in the action and one badly wounded crewman was captured ashore.[52]

1966

After Division 13's arrival at Cat Lo on 22 February 1966, operations started at nearby Rung Sat Special Zone;[55] an area of tidal mangrove swamp southeast of Saigon that straddled the Long Tau River, the main shipping channel to the Port of Saigon. Point White was patrolling on the night of 9 March and intercepted a small junk attempting to smuggle supplies across the Soai Rạp River. After hailing the junk and receiving automatic weapons fire in reply, the cutter returned fire and killed several Viet Cong. They continued to fire on Point White so the skipper ordered the helmsman to ram the junk amidships at full speed. All but four of the crew of the junk were killed. One of the survivors turned out to be a key leader in the Viet Cong Rung Sat infrastructure.[56] On 15 March Point Partridge engaged and damaged another junk, but shallow water allowed the junk to escape.[45] On 22 March Point Hudson drew fire from another junk on the river. In the battle that followed, an estimated ten Viet Cong were killed.[45] In conjunction with a joint U.S. Navy and U.S. Marine Corps operation designated Operation Jackstay, several Division 13 cutters were ordered to patrol the lower portion of the Soi Rap River in an effort to deny food, water, and ammunition to the Viet Cong operating in the Rung Sat Special Zone.[57] From the start of patrols on 10 March until the ships of the amphibious ready group put the Marines ashore on the Long Thành peninsula[58] on 26 March, Division 13 cutters had taken fire from the shore almost every night during patrol operations. Some of the most intense combat operations that Squadron One encountered occurred during the month of March 1966 in support of Operation Jackstay.[57] The joint operation ended 6 April with the withdrawal of the Marine Amphibious Force but the skipper of Point Partridge decided to continue the patrols after the operation ended. On the night patrols from 1 to 6 May Point Partridge engaged Viet Cong junks or received fire from the shore every night.[57]

While patrolling off the coast of the Ca Mau Peninsula in the late evening hours of 9 May 1966 Point Grey reported sighting two large bonfires on the shore near the mouth of the Rach Gia River. Since this was an unusual activity the skipper decided to monitor the area for the remainder of the night. Shortly after midnight, a steel-hulled trawler was spotted and challenged but Point Grey received no answer. The trawler continued on a course headed for the beach area near the bonfires and ran aground 400 yards (370 m) from the shore.[59] After daybreak Point Grey attempted to board the trawler but encountered heavy fire from the shore. After requesting assistance from the CSC, Point Grey stood off from the trawler until destroyer escort USS Brister arrived on scene. With Brister standing in deeper water and South Vietnamese Air Force A-1E Skyraider aircraft bombing the beach nearby, Point Grey attempted a boarding but she received very heavy small arms fire from Viet Cong positions beyond the beach which heavily damaged the bridge and wounded three of her crew manning the mortar on the bow.[60] With evening approaching it was decided by CSC to destroy the trawler and Point Grey assisted by Point Cypress began mortaring the trawler. During the shelling an explosion on board the trawler broke it in two pieces and caused it to sink in the shallow waters. Salvage operations began the next morning and included the recovery of six crew served weapons and 15 short tons (14,000 kg) of ammunition of Chinese manufacture.[59] The destruction of the trawler marked the first instance of the capture of a trawler by Market Time assets.[61][62]

While on patrol near the mouth of the Co Chien River in the early hours of 20 June, the skipper of Point League noted a large radar contact which, upon further investigation, was found to be running without navigation lights. After informing the CSC of the situation the cutter went to general quarters and spotlighted the incoming trawler. The trawler ignored a hail from Point League and two bursts of machine gun fire across its bow.[63] The trawler returned with heavy machine gun fire hitting the cutter's bridge and wounding the executive officer and a crewman manning the mortar on the forecastle. The trawler dropped the line on a towed junk and picked up speed in an effort to beach along the shore. When the commanding officer of Point League noticed that the trawler was headed for shoal water near the mouth of the river, he let the trawler run aground 75 yards (69 m) from shore and moved to a position 1,000 yards (910 m) away while keeping the target illuminated with mortar rounds. Point League then came under fire from Viet Cong elements operating from just behind the shoreline. With assistance from Point Slocum the two cutters poured machine gun fire into the grounded trawler. Just after dawn the trawler was sunk by what was probably a scuttling charge resulting in a large fire. At 07:15 destroyer escort USS Haverfield arrived on scene and assumed control of the operation. With the assistance of two U.S. Air Force F-100 Super Sabre aircraft providing close air support, resistance from the shoreline was finally controlled. It was decided by the commanding officer of the Haverfield that salvage of the trawler would be attempted in order to learn more about the trawler, its origins and the cargo on board.[64] The crews of the two cutters were joined by Point Hudson and dock landing ship USS Tortuga and several RVN junks in fighting the fire and beginning salvage operations.[30][64] After patching the hull and dewatering; the trawler was eventually towed to the RVN shipyard at Vung Tau. The 99-foot (30 m) trawler yielded valuable information about the capabilities of that particular class of trawler. It was carrying about 100 short tons (91,000 kg) of small arms and ammunition of recent manufacture in China and North Korea. The surviving log and navigation charts helped determine the trawler's origin and two possible destinations.[64]

Point Welcome incident

Point Welcome was patrolling Area 1A1 immediately south of the DMZ in the early morning hours of 11 August 1966. At 03:40 the cutter was illuminated by an U.S. Air Force forward air controller (FAC) who mistook her for an enemy vessel. The FAC called in one B-57 Canberra tactical bomber and two F-4 Phantom fighter-bomber aircraft which proceeded to strafe the cutter for about one hour, each making from seven to nine passes. Point Welcome turned on all of her running and docking lights when first illuminated by the FAC aircraft and contacted the CSC by radio telling them that they were being illuminated by aircraft. During the first pass all of the crew on the bridge were wounded and the commanding officer, Lieutenant Junior Grade David Brostrom, was killed along with the helmsman, Engineman Second Class Jerry Phillips.[65] All signaling equipment, electronics and radios were knocked out on the first pass. Point Welcome began evasive maneuvers at the direction of Chief Boatswains Mate Richard Patterson, who had assumed command after the executive officer was seriously injured. Patterson attempted to avoid the illumination lights of the attacking aircraft and move out of the way of the strafing aircraft. At 04:15 Patterson decided that the best course of action was to beach the cutter and move the wounded ashore, however when this was attempted, the crew came under fire from unknown sources from the shoreline. At 04:25 Point Orient and Point Caution arrived on the scene and started rescue proceedings. In addition to the commanding officer, one other crewman was killed, nine other crewmen were injured along with a RVN liaison officer and civilian freelance journalist Tim Page. The bridge of the cutter was severely damaged and despite nine 5 to 9 inch (13 to 23 cm) wide holes in the main deck, the hull was undamaged. Point Welcome was escorted back to Da Nang under her own power and required three months to repair the damage.[66][67][68] Patterson saved the cutter and the surviving crew at great risk to himself. He was awarded a Bronze Star with the combat "V" device for his actions.[69]

After eight days of testimony the findings of a board of investigation conducted by MACV were forwarded to the Commandant of the Coast Guard:

It is evident from the record that there was a lack of communication between different forces operating in the same area, and that existing orders and instructions pertaining to identification and recognition of friendly forces were not observed.

- —extract from 9 November 1966 letter from MACV to Commandant, USCG[70]

As a result of the investigation, lines of communication were set up between the Navy and the Air Force. The Air Force knew nothing of Operation Market Time and did not routinely communicate with Naval Forces, Vietnam. To avoid a repetition of the incident, aircraft patrolling near the DMZ were instructed not to attack vessels without first contacting CSC Da Nang for clearance.[70][71]

1967

In the late evening hours of 1 January 1967 Point Gammon along with two U.S. Navy vessels, PCF-68 and PCF-71, intercepted a trawler attempting to land supplies on the Cau Mau Peninsula. After running the trawler aground the PCFs managed to hit it with several mortar rounds while Point Gammon kept the trawler illuminated. Several secondary explosions occurred and the trawler disappeared. Investigations later concluded that the trawler could have successfully escaped to a nearby river although heavily damaged.[72]

A more successful action was fought in the early morning hours of 14 March 1967 when a U.S. Navy patrol aircraft spotted a trawler near Cu-Lao Re, an island 65 miles (105 km) southeast of Da Nang.[73] USS Brister and two PCFs along with Point Ellis closed on the trawler and forced it aground near the village of Phouc Thien on Cape Batangan.[74] The patrol elements continued to exchange heavy gunfire with the trawler and land-based Viet Cong units until dawn when the trawler was scuttled with a massive explosion. Investigators later discovered a heavy machine gun, a recoilless rifle, sub-machine guns, rifles and carbines along with thousands of rounds of ammunition. Also in the wreckage was a complete surgical kit for a field hospital and medical supplies.[75]

A similar conclusion was the result of the capture of a steel hull trawler 15 July 1967 after three days of tracking by patrol aircraft and the radar picket, USS Wilhoite.[76] After playing a cat-and-mouse game for three days with TF115 units the trawler headed for the mouth of the Sa Ky River on the Batangan Peninsula late on 14 July.[77] The trawler was directed by Point Orient to heave to, but the hail was answered with gunfire.[78] The cutter returned fire along with Wilhoite and gunboat USS Gallup, destroyer USS Walker, and PCF-79. At 02:00 on 15 July, the trawler was boxed in and ablaze, and ran aground 200 yards (180 m) from shore. South Korean marines directed artillery fire from the shore and at 06:00 with the trawler apparently abandoned, a U.S. Navy demolitions expert from Walker boarded the trawler and defused 2,000 pounds of TNT charges that were designed to scuttle the craft.[76] Found on board were several thousand rounds of rifle and machine gun ammunition, mortar and rocket rounds, anti-personnel mines, grenades, and several thousand pounds of C-4 plastic explosive and TNT. Weapons found included several hundred machine guns, AK-47 rifles, AK-56 rifles, and B-40 rocket launchers.[76]

On many occasions during the months of October, November and December 1967, the cutters Point Hudson, Point Jefferson, Point Grace and Point Gammon were called on to assist in naval gunfire support missions in the Long Toan and Thanh Phu Secret Zones near Soc Trang.[79][80] These missions resulted in the destruction of several sampans and structures as well as bunkers used by the Viet Cong.[81][82][83]

1968

During the morning hours of 31 January 1968, combined forces of North Vietnamese Army/Viet Cong personnel initiated coordinated attacks on military installations throughout South Vietnam in what would be later be referred to as the Tet Offensive. Because of monsoon weather in the northern provinces of South Vietnam and a general curfew imposed by South Vietnam on most sampan traffic, routine boardings by Squadron One vessels during February were far below normal.[84] However, requests for naval gunfire support by land-based U.S. Army and U.S. Marine units increased significantly after Tet. The cutters Point Gammon, Point Arden, Point Grey, Point Cypress, Point League, and Point Slocum were involved in multiple naval gunfire support missions throughout the month of February.[84] The use of Squadron One cutters as a blocking force against exfiltration by NVA/VC forces operating along the coastline also increased at this time.[84]

During an action on 1 March 1968, in the early morning several Squadron One cutters were involved in the interdiction and destruction of four North Vietnamese trawlers attempting to smuggle arms and ammunition into South Vietnam at different locations. This co-ordinated attempt by the North Vietnamese was met by various elements of TF115; including U.S. Navy aircraft and vessels, RVN junks, U.S. Air Force aircraft, and U.S. Army helicopters. In addition, there were several Owasco-class cutter cutters from Coast Guard Squadron Three – Androscoggin, Winona, and Minnetonka – as well as Point Grey, Point Hudson, and Point Welcome from Squadron One.[84] As a result of this action, three North Vietnamese trawlers were destroyed and a fourth was turned back before it could reach the coast. After this action the incidence of smuggling by trawler was decreased and Communist forces had to resort to shipments along the Ho Chi Minh trail or through the port of Sihanoukville in Cambodia.[9]

While on patrol just south of the DMZ in the early morning hours of 16 June 1968 Point Dume reported seeing two rockets fired from an unidentified source hit U.S. Navy PCF-19, which sank very quickly with the loss of five crew.[85] Shortly thereafter, Point Dume came under fire from an unidentified aircraft along with the heavy cruiser USS Boston and the Royal Australian Navy destroyer HMAS Hobart. The duration of the attack was about one hour with little damage to the cutter and Boston but considerable damage to Hobart with two sailors killed and eight wounded.[86] Evidence during a board of inquiry later showed that it was a friendly fire incident involving U.S. Air Force and U.S. Navy aircraft mistaking the ships for enemy targets.[85][87] This incident and the 11 August 1966 friendly fire incident involving Point Welcome caused several procedures for the identification of naval vessels by U.S. Navy, U.S. Marine and U.S. Air Force aircrews to change.[70]

Operations conducted by South Vietnamese Regional Force troops on Phu Quoc Island in September were assisted by Market Time assets. Point Partridge and Point Banks assisted with naval gunfire support on 9 September which destroyed three bunkers, killing four and wounding several others. Ten Viet Cong were captured.[88] On 20 September, Point Cypress and RVN MSC-116 assisted Regional Forces troops that had been ambushed by Viet Cong forces by lending naval gunfire support. Point Hudson, Point Kennedy, and U.S. Navy PCF-50 and PCF-3 arrived shortly after the action started and joined in the gunfire support. Small boats from the cutters helped evacuate wounded Regional Force troops.[88]

Heavy weather in the form of monsoons in the northern half of South Vietnam reduced indigenous coastal traffic during October 1968 and the U.S. Navy's PCF support of Market Time was limited by heavy seas; however, Market Time units including Squadron One cutters fired a record number of naval gunfire missions for the sixth month in a row. The 1,027 missions conducted during October was 19 percent higher than the previous record.[89]

On 5 December 1968, three crewmen operating the small boat from Point Cypress in a small stream on the Ca Mau Peninsula were ambushed, severely wounding two and killing the third, Fireman Heriberto S. Hernandez.[65][90] Zumwalt awarded a Bronze Star Medal with "V" Device posthumously to Hernandez for his heroic actions in saving his fellow crewmen's lives.[91][92]

1969

In February 1969, Squadron One personnel began training RVN engineers in the maintenance and repair of the Point class cutters that would eventually be turned over to the South Vietnamese government under the "Vietnamization" program.[93]

On 22 March during routine operations involving the inspection of fishing craft for contraband arms and supplies, the chief engineer, Chief Engineman Morris S. Beeson of the Point Orient was killed by ambush fire from three shore positions while attempting to board a sampan near Qui Nhon.[65][94][95]

On 27 March, Point Dume was notified by a unit of the U.S. Army's 173rd Airborne Brigade that a Viet Cong unit was located at a village 40 miles (64 km) north of Qui Nhon and Point Dume was requested to perform a blocking patrol while the brigade's troops conducted a sweep. Point Dume assisted with naval gunfire support. Additionally, in the aftermath, a landing party helped to destroy 41 sampans that had been used to transport Viet Cong supplies.[95]

The first turnover of Squadron One cutters occurred on 16 May with the transfer of Point League and Point Garnet to the South Vietnamese Navy under the Vietnamization plan. An elaborate ceremony was held at the RVN Base in Saigon with dignitaries from many area naval activities witnessing the turnover of the two cutters.[96] On 5 June, Division 11 was disestablished and its cutters were transferred to Division 13.[97] The need for Squadron One cutters had been supplanted by the shallower draft PCFs and PBRs that were being concentrated in the Delta region for use in Operation Sealords. With better foul weather stationkeeping abilities than the U.S. Navy craft, the Point-class cutters of the Squadron were shifted for use during the northeast monsoon season in the northern half of the country.[78]

On 9 August while conducting a harassment and interdiction mission aboard Point Arden, a misfire occurred with the mortar killing Lieutenant Junior Grade Michael W. Kirkpatrick, the cutter's executive officer, and Engineman First Class Michael H. Painter.[41][65][98]

1970 – Vietnamization and disestablishment

With the growing dissatisfaction of the American electorate about Vietnam in 1969, high officials in the Nixon Administration sought a way to disengage the United States from the war.[99][100] Part of the strategy to placate public opinion was termed "Vietnamization" and it included plans to remove most U.S. combat troops from Vietnam and the turnover of supplies and equipment to the South Vietnamese military.[101][102][103] Other parts of the plan, referred to as Accelerated Turnover to Vietnamese (ACTOV), included the training of Vietnamese in the use of equipment that was to be turned over to them and a gradual phase-in of responsibilities for the conduct of the war by the South Vietnamese government.[99][104][105] The first assets turned over to the Vietnamese under ACTOV occurred on 1 February 1969 when 25 mostly smaller U.S. Navy vessels were transferred to the RVN to be used in supporting Operation Sealords in the Mekong Delta.[106]

The disestablishment of COGARDRON ONE upon turnover of the final WPBs to South Vietnam marks a significant step in Vietnamization. The Coast Guard performance in Vietnam operations has been characterized by the highest professionalism, traditional with the Coast Guard, and has been recognized by every Navy man, both U.S. and Vietnamese, who have had occasion to work with and receive support from WPBs. The record and reputation achieved by COGARDRON ONE have earned our highest respect.

- – Admiral John J. Hyland, USN, Commander, Pacific Fleet,

25 August 1970[107]

- – Admiral John J. Hyland, USN, Commander, Pacific Fleet,

ACTOV

The naval assets portion of the ACTOV plan consisted of two parts: SCATTOR (Small Craft Assets, Training, and Turnover of Resources) and VECTOR (Vietnamese Engineering Capability, Training of Ratings). While SCATTOR trained Vietnamese replacement crews for the patrol boats of Squadron One, VECTOR trained and prepared Vietnamese repair personnel to maintain them.[108]

Background

Since the patrol boats of Squadron One were an essential part of the blockade of war supplies entering South Vietnam from North Vietnam, it was decided that they would be transferred to the South Vietnamese navy after crews had been trained to operate them effectively. On 2 November 1968, Zumwalt, Commander, Naval Forces Vietnam, presented a plan to General Creighton W. Abrams, Commander, MACV to turn over all U.S. Navy and U.S. Coast Guard resources to the RVN by 30 June 1970.[99] Abrams approved the Navy's plan with the caveat that any equipment turned over to the Vietnamese would have to be in first-class condition and that they would have to be properly trained in its use.[108] The Navy plan called for the enlisted Vietnamese personnel to report aboard vessels for training first with the officers finally reporting aboard after the crews were trained. In a recommendation made 14 January 1969, the Commander, Coast Guard Activities Vietnam, Captain Ralph W. Niesz, suggested that English speaking Vietnamese officers report aboard first and be given the chance to receive extensive procedural training with Coast Guard crews before any junior personnel report aboard. Neisz cited cultural imperatives that required seniors to be more knowledgeable than subordinates and that it would be very difficult for officers to accept instruction from junior personnel without losing face. Zumwalt agreed with the Coast Guard plan enthusiastically and ordered it implemented immediately.[108][109]

On 3 February 1969 the first RVN officers reported aboard Point Garnet and Point League for an 18-week pilot training program. Each cutter's executive officer was relieved and assigned staff duties ashore with the commanding officer assuming his duties. The two spare bunks on each cutter were utilized by the new Vietnamese personnel reporting on board. As experience was gained by the Vietnamese crew members, new junior personnel reported in pairs replacing Coast Guardsmen that were then assigned ashore to assist with the VECTOR phase of training.[99][109] The first transfer of Squadron One cutters occurred at the RVN Base in Saigon during joint decommissioning and commissioning ceremonies held 16 May 1969 by the Coast Guard and the RVN. Point Garnet and Point League were the first cutters transferred under the ACTOV plan.[96]

Problems

SCATTOR training was not easy for either the trainers or the trainees. Cultural differences and language barriers had to be breached by both. English–Vietnamese dictionaries were used extensively and Vietnamese sailors who spoke even broken English were often pressed into service to help translate the training syllabus for each job on the cutter. Coast Guardsmen that had maintained their cutters with pride could not understand the Vietnamese sailors seeming lack of care about housekeeping chores.[110] Orders dictated that any cutter entering the ACTOV Program had to be ready for turnover within four months.[109] Often after a return from patrol duties the Vietnamese sailors would just leave the cutter as soon as it reached homeport, leaving maintenance, cleanup, and re-provisioning to the Coast Guardsmen.[111] AWOL rates for Vietnamese sailors often interfered with training schedules as well as patrol operations. Morale of the Coast Guardsmen charged with the training of the replacement Vietnamese crew was often very low and this caused friction between the two parts of the crew.[111] Because of political pressures in the United States to end involvement in the war as soon as possible, the SCATTOR program of training was accelerated to a 15-week program and eventually an 11-week program. This caused overcrowding on the cutters and further problems with the mixed crews.[110][111]

All of the Squadron One cutters eventually completed training of the Vietnamese crews and as cutters were transferred to the RVN each division shrunk in size until they were consolidated with other divisions. Division 11 was disestablished on 5 June 1969 with the remaining cutters in the division moving to Cat Lo. Division 12 was consolidated with Division 13 at Cat Lo 16 March 1970.[96]

Last patrols

After Point Grey and Point Orient were turned over to the RVN on 14 July only Point Cypress and Point Marone were left in Division 13. On that day the remaining two cutters were given orders to report to the lower Mekong Delta and provide support for operations in the Than Phu Secret Zone.[96] On 19 and 20 July the crews of both cutters consisted of a full complement of 13 RVN sailors and 5 Coast Guardsmen including the commanding officers. Kit Carson Scouts were also embarked, making the decks very crowded. The Scouts were put ashore on a search and destroy mission and the cutters backed them up with gunfire from their decks and the cutter small boats.[96] The raid was successful, netting several captured Viet Cong troops and boxes of documents.[112] A week later both cutters with Australian Army explosive ordnance disposal soldiers aboard cruised the My Thanh River and destroyed fortifications.[112][113]

On 4 August 1970, coincidentally Coast Guard Day, the pair of cutters set out on what would prove to be their last combat patrol. Each cutter had 25 Kit Carson Scouts embarked for a patrol of the Co Chien River. While following a narrow canal leading off the main channel, Point Marone was the target of a command detonated mine. The blast killed two of the RVN sailors instantly; all five Coast Guardsmen were injured along with 10 Kit Carson Scouts.[112][114] After the mine explosion, Point Marone listed to starboard but managed to get underway while Point Cypress laid down suppressing fire and escorted the damaged cutter back to base at Cat Lo. Point Marone suffered three shrapnel holes at the starboard waterline as well as extensive damage to the bridge windows and damage to the watertight door between the mess deck and the forward berthing space. The deck aft of the bridge was covered with three inches of mud.[99] After patching and painting, Point Marone was prepared for a final Operational Readiness Inspection to check the RVN crew readiness for the pending turnover of both Point Marone and Point Cypress.[112][115]

Last turnover

With the turnover of Point Cypress and Point Marone to South Vietnamese navy on 15 August 1970, Squadron One and its remaining division, Division 13, were decommissioned. Over 3,000 Coast Guardsmen had served with Squadron One in Vietnam since May 1965. Administrative and liaison functions that had been carried out by the Squadron One staff were turned over to the Office of the Senior Coast Guard Officer, Vietnam (SCGOV).[96][116][117] Several officers of Squadron One were assigned temporary duties as advisors to former Squadron One cutters to further assist the new RVN commanding officers in their new duties.[117] The Coast Guard continued to provide technical assistance and training under the SCATTOR/VECTOR programs for the SVN after Squadron One was disestablished through the formation of four Technical Assistance Groups. Each group was composed of an officer and eight to eleven engineers reporting to SCGOV. The groups were located at Da Nang where there were six cutters assigned; Cam Ranh Bay, six cutters; Vung Tau, eight cutters; and An Thoi, six cutters. As tours of duty for each Coast Guardsman ended, U.S. Navy personnel gradually took over the training duties.[116][117]

Civic action

U.S. Coast Guard personnel stationed in Vietnam were encouraged by their commands to donate off duty time to assist in various civic action programs supporting the Vietnamese people. Squadron One personnel participated as time permitted in an island adoption program that was designed to provide educational materials and medical treatment to inhabitants of the many coastal islands in their area of operation. This program was offered to counter Viet Cong propaganda and promote a better understanding of the South Vietnamese government and USAID rural development programs.[118] Since medical personnel were normally not a part of the make-up of the Squadron One patrol boat crews, medical corpsmen were borrowed from Squadron Three cutters or nearby U.S. Navy units. Division 11 crews constructed a fresh water well and distribution system in addition to constructing voting booths on Hon Thom Island.[119][120][121] Division 12 cutters helped evacuate refugees from the vicinity of Cape Batangan when military operations intensified during 1967.[118] Division 13 personnel spent many hours of off duty time at the children's ward of the U.S. Army 36th Medevac Hospital and gave games, toys, clothing and candy to injured Vietnamese children.[122] During the Christmas holidays, at local orphanages all squadron personnel distributed gifts of candy and toys as well as clothing, soap and toothpaste that had been donated by Coast Guard families in the United States and brought to Vietnam on the Commandant's airplane.[121] Squadron One crews arranged for transportation of a small girl by an U.S. Air Force helicopter to USS Sanctuary for eye surgery while the squadron commander personally delivered a cornea for transplant.[118][123]

Legacy and impact

The cutters of Squadron One made a significant contribution to the success of Operation Market Time by forcing the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese forces to rely on the difficult Ho Chi Minh trail for most of their supplies and reinforcements.[124][125] During the period between 27 May 1965 and 15 August 1970 the squadron cruised 4,215,116 miles (6,783,572 km) and boarded 236,396 vessels while detaining 10,286 persons. During 4,461 naval gunfire missions they damaged or destroyed 1,811 enemy vessels and killed or wounded 1,232 enemy personnel.[126]

Unit and service awards

- Presidential Unit Citation

The Presidential Unit Citation (Navy) was awarded for extraordinary heroism and outstanding performance to units participating in Operation Sealords for the period 18 October to 5 December 1968 and included the Squadron One cutters Point Cypress, Point White, Point Grace, Point Young, Point Comfort, Point Mast, Point Marone, Point Caution, and Point Partridge.[2]

- Navy Unit Commendation

The Navy Unit Commendation was awarded for exceptionally meritorious service to the United States Navy Coastal Surveillance Force (Task Force 115) which included the administrative staff of Squadron One and Division 11 for service during period 1 January 1967 to 31 March 1968; Division 12, 1 January to 28 February 1967; and Division 13, 1 January to 10 May 1967.[3][127]

- Navy Meritorious Unit Commendation

The Navy Meritorious Unit Commendation was awarded for meritorious service to units of the United States Navy Coastal Surveillance Force (Task Force 115) which included the following Squadron One cutters: Point White, Point Arden, Point Dume, Point Glover, Point Jefferson, Point Kennedy, Point Young, Point Partridge, Point Caution, Point Welcome, Point Banks, Point Lomas, Point Grace, Point Mast, Point Grey, Point Orient, Point Cypress, and Point Marone.[4]

- Vietnam Service Medal

Although the Vietnam Service Medal is a personal service award, it is permissible and customary under Coast Guard regulations for cutters to display service awards on the port and starboard bridge wings.[128] Squadron One cutters were entitled to display the VSM by virtue of having served in Vietnam for more than thirty days during the eligibility period of 15 November 1961 to 30 April 1975.[129]

- Republic of Vietnam Gallantry Cross Unit Citation with Palm

All units serving under MACV were awarded the Vietnam Gallantry Cross Unit Citation with Palm by South Vietnam. Because U.S. Navy units serving in Vietnam were subordinate to MACV this included all Coast Guard Squadron One cutters.[130]

- Republic of Vietnam Campaign Medal

The Vietnam Campaign Medal was an award of South Vietnam for those individuals who served in Vietnam for a period of at least six months. Although it was a personal award, Coast Guard regulations permitted its display on a cutter's port and starboard bridge wings since Squadron One's cutters served during the eligibility period of 1 March 1961 to 28 March 1973.[128][131]

Cutter assignment and disposition information

Legend:

Denotes initial assignment to Division 11

Denotes initial assignment to Division 12

Denotes initial assignment to Division 13

| Name | Hull number | Commissioned | Decommissioned[Note 3] | Homeport [132] | Disposition [132][Note 4] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Point Caution | WPB-82301 | 5 Oct 1960 | 29 Apr 1970 | Galveston, Texas 61–65; Division 12, RVN 65–70 | Transfer to RVN as RVNS Nguyen An (HQ-716) 29 Apr 1970 |

| Point Young | WPB-82303 | 26 Oct 1960 | 16 March 1970 | Grand Isle, Louisiana 61–65; Division 11, RVN 65–70 | Transfer to RVN as RVNS Tran Lo (HQ-714) 16 March 1970 |

| Point League | WPB-82304 | 9 Nov 1960 | 16 May 1969 | Morgan City, Louisiana 61–65; Division 13, RVN 65–69 | Transfer to RVN as RVNS Le Phuoc Duc (HQ-700) 16 May 1969,[96] |

| Point Partridge | WPB-82305 | 23 Nov 1960 | 27 March 1970 | Beals and West Jonesport, Maine 61–65; Division 13, RVN 66–70 | Transfer to RVN as RVNS Bui Viet Thanh (HQ-715) 27 March 1970 |

| Point Jefferson | WPB-82306 | 7 Dec 1960 | 21 Feb 1970 | Nantucket, Massachusetts 61–65; Division 13, RVN 65–70 | Transfer to RVN as RVNS Le Ngoc An (HQ-712) 21 Feb 1970 |

| Point Glover | WPB-82307 | 7 Dec 1960 | 14 Feb 1970 | Fort Hancock, New Jersey 61–65; Division 11, RVN 65–70 | Transfer to RVN as RVNS Dao Van Dang (HQ-711) 14 Feb 1970 |

| Point White | WPB-82308 | 18 Feb 1961 | 12 Jan 1970 | New London, Connecticut 61–65; Division 13, RVN 66–70 | Transfer to RVN as RVNS Le Dinh Hung (HQ-708) 12 Jan 1970 |

| Point Arden | WPB-82309 | 1 Feb 1961 | 14 Feb 1970 | Pt. Pleasant, New Jersey 61–65; Division 12, RVN 65–70 | Transfer to RVN as RVNS Pham Ngoc Chau (HQ-710) 14 Feb 1970 |

| Point Garnet | WPB-82310 | 15 Mar 1961 | 16 May 1969 | Norfolk, Virginia 61–65; Division 11, RVN 65–69 | Transfer to RVN as RVNS Le Van Nga (HQ-701) 16 May 1969[96] |

| Point Slocum | WPB-82313 | 12 Apr 1961 | 11 Dec 1969 | St. Thomas, VI 61–65; Division 13, RVN 66–69 | Transfer to RVN as RVNS Nguyen Ngoc Thach (HQ-706) 11 Dec 1969 |

| Point Clear | WPB-82315 | 26 Apr 1961 | 15 Sep 1969 | San Pedro, California 61–65; Division 11, RVN 65–69 | Transfer to RVN as RVNS Huynh Van Duc (HQ-702) 15 Sep 1969 |

| Point Mast | WPB-82316 | 10 May 1961 | 15 Jun 1970 | Long Beach, California 61–65; Division 11, RVN 65–70 | Transfer to RVN 15 Jun 1970[Note 5] |

| Point Comfort | WPB-82317 | 24 May 1961 | 17 Nov 1969 | Benicia, California 61–65; Division 11, RVN 65–69 | Transfer to RVN as RVNS Dao Thuc (HQ-704) 17 Nov 1969 |

| Point Orient | WPB-82319 | 28 Jun 1961 | 14 Jul 1970 | Ft. Pierce, Florida 61–65; Division 12, RVN 65–70 | Transfer to RVN as RVNS Nguyen Kim Hung (HQ-722) 14 Jul 1970 |

| Point Kennedy | WPB-82320 | 19 Jul 1961 | 16 Mar 1970 | San Juan, PR 61–65; Division 13, RVN 66–70 | Transfer to RVN as RVNS Huynh Van Ngan (HQ-713) 16 Mar 1970 |

| Point Lomas | WPB-82321 | 9 Aug 1961 | 23 May 1970 | Port Aransas, Texas 61–65; Division 12, RVN 65–70 | Transfer to RVN 23 May 1970[Note 6] |

| Point Hudson | WPB-82322 | 30 Aug 1961 | 11 Dec 1969 | Panama City, Florida 61–65; Division 13, RVN 65–69 | Transfer to RVN as RVNS Dang Van Hoanh (HQ-707) 11 Dec 1969 |

| Point Grace | WPB-82323 | 27 Sep 1961 | 15 Jun 1970 | Crisfield, Maryland 61–65; Division 13, RVN 66–70 | Transfer to RVN 15 Jun 1970[Note 7] |

| Point Grey | WPB-82324 | 11 Oct 1961 | 14 Jul 1970 | Norfolk, Virginia 61–65; Division 11, RVN 65–70 | Transfer to RVN as RVNS Huynh Bo (HQ-723) 14 Jul 1970 |

| Point Dume | WPB-82325 | 1 Nov 1961 | 14 Feb 1970 | Fire Island, New York 61–65; Division 12, RVN 65–70 | Transfer to RVN as RVNS Truong Tien[134] (HQ-709) 14 Feb 1970 |

| Point Cypress | WPB-82326 | 22 Nov 1961 | 15 Aug 1970[135] | Boston, Massachusetts 61–65; Division 13, RVN 66–70 | Transfer to RVN as RVNS Ho Duy (HQ-724) 15 Aug 1970[135][Note 8] |

| Point Banks | WPB-82327 | 13 Dec 1961 | 26 Mar 1970 | Woods Hole, Massachusetts 61–65; Division 11, RVN 66–70 | Transfer to RVN 26 Mar 1970[Note 9] |

| Point Gammon | WPB-82328 | 31 Jan 1962 | 11 Nov 1969 | Ft. Bragg, California 62–65; Division 12, RVN 65–69 | Transfer to RVN as RVNS Nguyen Dao (HQ-703) 11 Nov 1969 |

| Point Welcome | WPB-82329 | 14 Feb 1962 | 29 Apr 1970 | Everett, Washington 62–65; Division 12, RVN 65–70 | Transfer to RVN as RVNS Nguyen Han (HQ-717) 29 Apr 1970 |

| Point Ellis | WPB-82330 | 28 Feb 1962 | 9 Dec 1969 | Port Townsend, Washington 62–65; Division 12, RVN 65–69 | Transfer to RVN as RVNS Le Ngoc Thanh (HQ-705) 9 Dec 1969 |

| Point Marone | WPB-82331 | 14 Mar 1962 | 15 Aug 1970 | San Pedro, California 62–65; Division 11, RVN 65–70 | Transfer to RVN as RVNS Truong Ba (HQ-725) 15 Aug 1970 |

See also

Notes

- Footnotes

- ^ The Kelley (2002) reference is divided into several sections with each section starting its page numbering with page 1, therefore citations for this reference follows the same pattern.

- ^ A discussion of the history and characteristics of the Mk 2 Mod 0 and Mod 1 naval mortar and machine gun combination mount is at: Stoner, Bob. "Mk 2 Mod 0 and Mod 1 .50 Caliber MG/81mm Mortar". Patrol Craft Fast. pcf45.com. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- ^ Sources do not always agree on decommissioning dates. Those conflicts are noted.

- ^ Sources do not always agree on disposition information. Those conflicts are noted.

- ^ The Coast Guard Historian's Office cites Point Mast being re-commissioned Ho Dang La and no hull number. Scotti cites Dam Thoai and a hull number of HQ-721.[133]

- ^ The Coast Guard Historian's Office cites Point Lomas being re-commissioned with only a hull number of HQ-718. Scotti cites Van Dien and a hull number of HQ-719.[133]

- ^ The Coast Guard Historian's Office cites Point Grace being re-commissioned Dam Thoai and no hull number. Scotti cites Ho Dang La and a hull number of HQ-720.[134]

- ^ Larzelere cites 15 August 1970 as decommissioning date of Point Cypress[135] while the Coast Guard Historian's Office[132] and Scheina[136] cite a decommissioning date of 11 November 1969. Larzelere cites a picture of the event on page 239 and an extract of the August 1970 monthly historical summary of the Commander, Naval Forces Vietnam on page 240 as his source.[116]

- ^ The Coast Guard Historian's Office cites Point Banks being re-commissioned with only a hull number of HQ-719. Scotti cites Ngo Van Quyen and a hull number of HQ-718.[137]

- Citations

- ^ "USCG in Vietnam Chronology" (pdf). U.S. Coast Guard History Program. U.S. Coast Guard Historian's Office. p. 1.

- ^ a b "Presidential Unit Citation (Navy)". Presidential Unit Citation (Navy). Mobile Riverine Force Association.

- ^ a b "Navy Unit Commendation". Navy Unit Commendation. Mobile Riverine Force Association.

- ^ a b "Meritorious Unit Commendation". Meritorious Unit Commendation. Mobile Riverine Force Association.

- ^ a b Kelley, sec 5, p 400

- ^ a b Kelley, sec 5, p 129

- ^ a b Kelley, sec 5, p 95

- ^ Larzelere, p 6

- ^ a b Summers, p 100

- ^ Tulich, p 3

- ^ Kelley, sec 5, p 541

- ^ a b Cutler, p 76

- ^ Karnow, pp 345–346

- ^ a b c Johnson, p 331

- ^ Cutler, p 81

- ^ Larzelere, p 7

- ^ a b Larzelere, p 13

- ^ Cutler, p 82

- ^ Larzelere, p 8

- ^ Wells II

- ^ a b Johnson, p 332

- ^ Scotti, p 9

- ^ a b Larzelere, p 18

- ^ a b Larzelere, p 19

- ^ Larzelere, p 15

- ^ a b c d Larzelere, p 21

- ^ Cutler, p 83

- ^ a b c Larzelere, p 22

- ^ Kelley, sec 5, p 142

- ^ a b Larzelere, p 72

- ^ a b c Larzelere, p 74

- ^ Larzelere, p 75

- ^ Larzelere, p 76

- ^ Scotti, p 16

- ^ Larzelere, p 77

- ^ Larzelere, p 28

- ^ Larzelere, p 30

- ^ Kelley, sec 5, p 116

- ^ Larzelere, p 48

- ^ a b Cutler, p 85

- ^ a b "USCG in Vietnam Chronology" (pdf). U.S. Coast Guard History Program. U.S. Coast Guard Historian's Office. p. 3.

- ^ Kelley, sec 5, p 83

- ^ Scotti, p 19

- ^ Larzelere, p 37

- ^ a b c Naval Historical Center, U.S. Navy (March 1966). "United States Naval Operations Vietnam, Highlights; March 1966". Naval Historical Center, U.S. Navy. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- ^ Scotti, p 18

- ^ a b Larzelere, p 34

- ^ a b Scotti, p 173

- ^ Larzelere, p 66

- ^ a b Larzelere, p 31

- ^ Cutler, p 84

- ^ a b Larzelere, p 45

- ^ Kelley, sec 5, p 208

- ^ Cutler, p 112

- ^ Kelley, sec 5, p 450

- ^ Larzelere, p 109

- ^ a b c Larzelere, p 83

- ^ Kelley, sec 5, p 303

- ^ a b Commander, Naval Forces Vietnam (May 1966). "Monthly Historical Summary. May 1966". Naval Historical Center, U.S. Navy. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- ^ Larzelere, p 64

- ^ Larzelere, p 61

- ^ Scotti, p 205

- ^ Larzelere, p 68

- ^ a b c Commander, Naval Forces Vietnam (June 1966). "Monthly Historical Summary. June 1966". Naval Historical Center, U.S. Navy. pp. 1–11. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- ^ a b c d "U.S. Coast Guardsmen Killed in Action during the Vietnam Conflict". Coast Guard History Frequently Asked Questions. U.S. Coast Guard Historian's Office. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- ^ Commander, Naval Forces Vietnam (August 1966). "Monthly Historical Summary. August 1966". Naval Historical Center, U.S. Navy. pp. 24–26. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- ^ Larzelere, pp 24–28

- ^ Scotti, pp 101–105

- ^ "Patterson Bronze Star Citation", Point Welcome, 1962, U.S. Coast Guard Historian's Office

- ^ a b c Scotti, p 110

- ^ Johnson, p 337

- ^ Commander, Naval Forces Vietnam (January 1967). "Monthly Historical Summary. January 1967". Naval Historical Center, U.S. Navy. pp. 29–30. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- ^ Kelley, sec 5, p 125

- ^ Kelley, sec 5, p 44

- ^ Commander, Naval Forces Vietnam (March 1967). "Monthly Historical Summary. March 1967". Naval Historical Center, U.S. Navy. pp. 23–26. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- ^ a b c Commander, Naval Forces Vietnam (July 1967). "Monthly Historical Summary. July 1967". Naval Historical Center, U.S. Navy. pp. 2–11. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- ^ Kelley, sec 5, p 443

- ^ a b Larzelere, p 35

- ^ Kelley, sec 5, p 304

- ^ Kelley, sec 5, p 502

- ^ Commander, Naval Forces Vietnam (October 1967). "Monthly Historical Summary. October 1967". Naval Historical Center, U.S. Navy. pp. 9–10. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- ^ Commander, Naval Forces Vietnam (November 1967). "Monthly Historical Summary. November 1967". Naval Historical Center, U.S. Navy. pp. 7–8. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- ^ Commander, Naval Forces Vietnam (December 1967). "Monthly Historical Summary. December 1967". Naval Historical Center, U.S. Navy. p. 7. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- ^ a b c d Commander, Naval Forces Vietnam (February 1968). "Monthly Historical Summary. February 1968". Naval Historical Center, U.S. Navy. pp. 1–20. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- ^ a b Cutler, p 114

- ^ Grey, pp 176–179

- ^ Commander, Naval Forces Vietnam (June 1968). "Monthly Historical Summary. June 1968". Naval Historical Center, U.S. Navy. pp. 4–5. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- ^ a b Commander, Naval Forces Vietnam (September 1968). "Monthly Historical Summary. September 1968". Naval Historical Center, U.S. Navy. pp. 2–4. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- ^ Commander, Naval Forces Vietnam (October 1968). "Monthly Historical Summary. October 1968". Naval Historical Center, U.S. Navy. p. 1. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- ^ Kelley, sec 5, p 97

- ^ "FN Heriberto Segovia Hernandez, USCG" (pdf). Coast Guard History Program. U.S. Coast Guard Historians Office. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- ^ Thiessen, William H. "Heriberto S. Hernandez" (pdf). Human Stories. Atlantic Area Historian, USCG. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- ^ Cutler, p 373

- ^ Kelley, sec 5, p 430

- ^ a b Commander, Naval Forces Vietnam (March 1969). "Monthly Historical Summary. March 1969". Naval Historical Center, U.S. Navy. p. 7. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Scotti, p 187

- ^ Larzelere, p 234

- ^ Scotti, p 164

- ^ a b c d e Larzelere, p 229

- ^ Mann, p 642

- ^ Karnow, p 593

- ^ Mann, p 644

- ^ Sorley, p 166

- ^ Karnow, p 595

- ^ Mann, p 652

- ^ Commander, Naval Forces Vietnam (February 1969). "Monthly Historical Summary. February 1969". Naval Historical Center, U.S. Navy. p. encl. 7. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- ^ Larzelere, p 225

- ^ a b c Larzelere, p 230

- ^ a b c Scotti, p 185

- ^ a b Scotti, p 186

- ^ a b c Larzelere, p 236

- ^ a b c d Scotti, p 188

- ^ Kelley, sec 5, p 475

- ^ Larzelere, p 227

- ^ Larzelere, p 238

- ^ a b c Commander, Naval Forces Vietnam (August 1970). "Monthly Historical Summary. August 1970". Naval Historical Center, U.S. Navy. p. 74. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- ^ a b c Larzelere, p 240

- ^ a b c Tulich, p 19

- ^ Kelley, sec 5, p 248

- ^ Scotti, p 153

- ^ a b Tulich, p 20

- ^ Tulich, p 21

- ^ Scotti, p 160

- ^ Kelley, sec F, p 32

- ^ Johnson, p 336

- ^ Scotti, p 219

- ^ Larzelere, p 118

- ^ a b "Coatings and Color Manual" (PDF). U.S. Coast Guard Coatings and Color Manual CG-263, 16 July 1973. U.S. Coast Guard Historian's Office. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- ^ Medals and Awards Manual, Enclosure 16, pp 1–5

- ^ "Republic of Vietnam Galantry Cross Unit Citation" (PDF). General Orders No. 8. Headquarters, Department of the Army. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ^ "Title 32 – National Defense, § 578.129, Republic of Vietnam Campaign Medal". Code of Federal Regulations. Government Printing Office. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ^ a b c ""Point" Class 82-foot WPBs". Assets. US Coast Guard Historians Office. Retrieved 15 April 2013. Coast Guard Historian website

- ^ a b Scotti, p 211

- ^ a b Scotti, p 210

- ^ a b c Larzelere, p 239

- ^ Scheina, p 69

- ^ Scotti, p 209

- Websites used

![]() This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: U.S. Coast Guard Cutters and Craft Index

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: U.S. Coast Guard Cutters and Craft Index

![]() This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: NHHC Organization Records Collections, Vietnam Operations

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: NHHC Organization Records Collections, Vietnam Operations

- "Commander Naval Forces Vietnam". Research Archives. Naval History and Heritage Command, U.S. Navy. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- "Medals and Awards Manual, Commandant Instruction M1625.25E" (pdf). Directives. U.S. Coast Guard. 15 August 2016. pp. 1–5, Enclosure 16. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- "Patterson Bronze Star Citation". Point Welcome, 1962. U.S. Coast Guard Historian's Office. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- "Point-Class 82-foot WPBs" (asp). U.S. Coast Guard Historian's Office. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- "Republic of Vietnam Galantry Cross Unit Citation" (PDF). General Orders No. 8. Headquarters, Department of the Army. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- "Title 32 – National Defense, § 578.129, Republic of Vietnam Campaign Medal". Code of Federal Regulations. Government Printing Office. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- "U.S. Coast Guardsmen Killed in Action during the Vietnam Conflict" (asp). Coast Guard History Frequently Asked Questions. U.S. Coast Guard Historian's Office. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- "USCG in Vietnam Chronology" (PDF). U.S. Coast Guard History Program. U.S. Coast Guard Historian's Office. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- Thiessen, William H. "Heriberto S. Hernandez" (pdf). Human Stories. Atlantic Area Historian, USCG. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- Tulich, Eugene N. (1975). "The United States Coast Guard in South East Asia During the Vietnam Conflict" (asp). Coast Guard Historical Monograph. 1. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- Wells II, William R. (August 1997). "The United States Coast Guard's Piggyback 81mm Mortar/.50 cal. machine gun". Vietnam Magazine. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- References used

- Cutler, Thomas J. (2000). Brown Water, Black Berets: Coastal and Riverine Warfare in Vietnam. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland. ISBN 978-1-55750-196-7.

- Grey, Jeffrey (1998). Up Top: The Royal Australian Navy and Southeast Asian Conflicts, 1955–1972. St. Leonards, New South Wales, Australia: Allen & Unwin in association with the Australian War Memorial. ISBN 1864482907.

- Johnson, Robert Irwin (1987). Guardians of the Sea, History of the United States Coast Guard, 1915 to the Present. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland. ISBN 978-0-87021-720-3.

- Karnow, Stanley (1983). Vietnam: A History. The Viking Press, New York City, New York. ISBN 978-0-670-74604-0.

- Kelley, Michael P. (2002). Where We Were in Vietnam. Hellgate Press, Central Point, Oregon. ISBN 978-1-55571-625-7.

- Larzelere, Alex (1997). The Coast Guard at War, Vietnam, 1965–1975. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland. ISBN 978-1-55750-529-3.

- Mann, Robert (2001). A Grand Delusion: America's Descent Into Vietnam. Basic Books, New York City, New York. ISBN 978-0-465-04369-9.

- Scheina, Robert L. (1990). U.S. Coast Guard Cutters & Craft, 1946–1990. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland. ISBN 978-0-87021-719-7.

- Scotti, Paul C. (2000). Coast Guard Action in Vietnam: Stories of Those Who Served. Hellgate Press, Central Point, Oregon. ISBN 978-1-55571-528-1.

- Sorley, Lewis (1999). A Better War. Harcourt, Inc., New York City, New York. ISBN 978-0-15-601309-3.

- Summers Jr., Harry G. (1995). Historical Atlas of the Vietnam War. Houghton Mifflin Co., New York City, New York. ISBN 978-0-395-72223-7.

External links

- Coast Guard Combat Veterans Association website

- U.S. Coast Guard Historian's Office official website[permanent dead link]

- U.S. Navy, Naval History and Heritage Command official website

- Notes on Mk 2 Mod 0 and Mod 1 .50 Caliber MG/81mm Mortar