Common murre

| Common murre | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | U. aalge

|

| Binomial name | |

| Uria aalge (Pontoppidan, 1763)

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Colymbus aalge Pontoppidan, 1763 | |

The common murre or common guillemot (Uria aalge) is a large auk. It is also known as the thin-billed murre in North America. It has a circumpolar distribution, occurring in low-Arctic and boreal waters in the North Atlantic and North Pacific. It spends most of its time at sea, only coming to land to breed on rocky cliff shores or islands.

Common murres have fast direct flight but are not very agile. They are more manoeuvrable underwater, typically diving to depths of 30–60 m (98–197 ft). Depths of up to 180 m (590 ft) have been recorded.

Common murres breed in colonies at high densities. Nesting pairs may be in bodily contact with their neighbours. They make no nest; their single egg is incubated on a bare rock ledge on a cliff face. Eggs hatch after ~30 days incubation. The chick is born downy and can regulate its body temperature after 10 days. Some 20 days after hatching the chick leaves its nesting ledge and heads for the sea, unable to fly, but gliding for some distance with fluttering wings, accompanied by its male parent. Chicks are capable of diving as soon as they hit the water. The female stays at the nest site for some 14 days after the chick has left.

Both male and female common murres moult after breeding and become flightless for 1–2 months. In southern populations they occasionally return to the nest site throughout the winter. Northern populations spend the winter farther from their colonies.

Taxonomy

The auks are a family of seabirds related to the gulls and terns which contains several genera. The common murre is placed in the guillemot (murre) genus Uria (Brisson, 1760), which it shares with the thick-billed murre or Brunnich's guillemot, U. lomvia. These species, together with the razorbill, little auk and the extinct great auk make up the tribe Alcini. This arrangement was originally based on analyses of auk morphology and ecology.[2]

The binomial name derives from Greek ouriaa, a waterbird mentioned by Athenaeus, and Danish aalge, "auk" (from Old Norse alka).[3]

The English "guillemot" is from French guillemot, probably derived from Guillaume, "William".[4] "Murre" is of uncertain origins, but may imitate the call of the common guillemot.[5]

Description

The common murre is 38–46 cm (15–18 in) in length with a 61–73 cm (24–29 in) wingspan.[6] Male and female are indistinguishable in the field and weight ranges between 945 g (2.083 lb) in the south of their range to 1,044 g (2.302 lb) in the north.[7] A weight range of 775–1,250 g (1.709–2.756 lb) has been reported.[8] In breeding plumage, the nominate subspecies (U. a. aalge) is black on the head, back and wings, and has white underparts. It has thin dark pointed bill and a small rounded dark tail. After the pre-basic moult, the face is white with a dark spur behind the eye. Birds of the subspecies U. a. albionis are dark brown rather than black, most obviously so in colonies in southern Britain. Legs are grey and the bill is dark grey. Occasionally, adults are seen with yellow/grey legs. In May 2008, an aberrant adult was photographed with a bright yellow bill.[9]

The plumage of first winter birds is the same as the adult basic plumage. However, the first pre-alternate moult occurs later in the year. The adult pre-alternate moult is December–February, (even starting as early as November in U. a. albionis). First year birds can be in basic plumage as late as May, and their alternate plumage can retain some white feathers around the throat.[6]

Some individuals in the North Atlantic, known as "bridled guillemots", have a white ring around the eye extending back as a white line. This is not a distinct subspecies, but a polymorphism that becomes more common the farther north the birds breed—perhaps character displacement with the northerly thick-billed murre, which has a white bill-stripe but no bridled morph. The white is highly contrasting especially in the latter species and would provide an easy means for an individual bird to recognize conspecifics in densely packed breeding colonies.[10]

The chicks are downy with blackish feathers on top and white below. By 12 days old, contour feathers are well developed in areas except for the head. At 15 days, facial feathers show the dark eyestripe against the white throat and cheek.[11]

Flight

The common murre flies with fast wing beats and has a flight speed of 80 km/h (50 mph).[12] Groups of birds are often seen flying together in a line just above the sea surface.[6] However, a high wing loading of 2 g/cm2[13] means that this species is not very agile and take-off is difficult.[14] Common murres become flightless for 45–60 days while moulting their primary feathers.[15]

Diving

The common murre is a pursuit-diver that forages for food by swimming underwater using its wings for propulsion. Dives usually last less than one minute, but the bird swims underwater for distances of over 30 m (98 ft) on a regular basis. Diving depths up to 180 m (590 ft) have been recorded[16] and birds can remain underwater a couple of minutes.

Distribution and habitat

The breeding habitat is islands, rocky shores, cliffs and sea stacks. The range is:

| Subspecies[17] | Range | Appearance |

|---|---|---|

| Uria aalge aalge | Nominate subspecies, eastern Canada, Greenland, Iceland, northern Ireland and Britain, southern Norway, possibly New England or a separate subspecies. | |

| U. a. albionis | Southern Ireland and Britain, France, Germany, Spain, Portugal | Smaller than nominate, chocolate brown upperparts |

| U. a. hyperborea | Northern Norway, Northwest Russia, Barents Sea | Larger than U. a. aalge, black upperparts |

| U. a. intermedia | Baltic Sea | Intermediate between U. a. aalge and U. a. albionis |

| U. a. spiloptera | Faroe Islands | |

| U. a. inornata | North Pacific, Japan, Eastern Russia, Alaska | Largest subspecies and largest auk, slightly larger than thick-billed murre |

| U. a. californica | California, Oregon, Washington, British Columbia |

Some birds are permanent residents; northern birds migrate south to open waters near New England, southern California, Japan, Korea and the western Mediterranean. Common murres rest on the water in the winter and this may have consequences for their metabolism. In the black-legged kittiwake (which shares this winter habit) resting metabolism is 40% higher on water than it is in air.[18]

The population is large, perhaps 7.3 million breeding pairs [19] or 18 million individuals.[1] It had been stable, but in 2016 a massive die-off of the birds in the northeast Pacific was reported. The birds seem emaciated and starving; no etiology has been found.[20] In general, potential threats include excessive hunting (legal in Newfoundland), pollution and oil spills.

Ecology and behaviour

Feeding

The common murre can venture far from its breeding grounds to forage; distances of 100 km (62 mi) and more are often observed[21] though if sufficient food is available closer by, birds only travel much shorter distances. The common murre mainly eats small schooling forage fish 200 mm (7.9 in) long or less, such as polar cod, capelin, sand lances, sprats, sandeels, Atlantic cod and Atlantic herring. Capelin and sand lances are favourite food, but what the main prey is at any one time depends much on what is available in quantity.[21] It also eats some molluscs, marine worms, squid, and crustaceans such as amphipods. It consumes 20–32 g (0.71–1.13 oz) of food in a day on average. It is often seen carrying fish in its bill with the tail hanging out.[10]

The snake pipefish is occasionally eaten, but it has poor nutritional value. The amount of these fish is increasing in the common murre's diet. Since 2003, the snake pipefish has increased in numbers in the North-east Atlantic and North Sea and sandeel numbers have declined.[22]

Communication

The common murre has a variety of calls, including a soft purring noise.

Reproduction

Colonies

The common murre nests in densely packed colonies (known as "loomeries"), with up to twenty pairs occupying one square metre at peak season.[citation needed] Common murres do not make nests and lay their eggs on bare rock ledges, under rocks, or the ground. They first breed at four to six years old and average lifespan is about 20 years.

Immature birds return to the natal colony, but from age 5 onwards ~25% of birds leave the colony, perhaps dispersing to other colonies.[23]

High densities mean that birds are close contact with neighbouring breeders.[24] Common murres perform appeasement displays more often at high densities and more often than razorbills.[24] Allopreening is common both between mates and between neighbours. Allopreening helps to reduce parasites, and it may also have important social functions.[25] Frequency of allopreening a neighbour correlates well with current breeding success.[25] Allopreening may function as a stress-reducer; ledges with low levels of allopreening show increased levels of fighting and reduced breeding success.[25]

Courtship

Courtship displays including bowing, billing and mutual preening. The male points its head vertically and makes croaking and growling noises to attract the females. The species is monogamous, but pairs may split if breeding is unsuccessful.[26][27]

Eggs and incubation

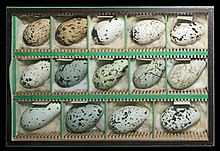

Common murre eggs are large (around 11% of female weight[17]), and are pointed at one end. There are a few theories to explain their pyriform shape:

- If disturbed, they roll in a circle rather than fall off the ledge.

- The shape allows efficient heat transfer during incubation.[28]

- As a compromise between large egg size and small cross-section. Large size allows quick development of the chick. Small cross-sectional area allows the adult bird to have a small cross-section and therefore reduce drag when swimming.[17]

Eggs are laid between May and July for the Atlantic populations and March to July for those in the Pacific. The female spends less time ashore during the two weeks before laying. When laying, she assumes a "phoenix-like" posture: her body raised upright on vertical tarsi; wings half outstretched. The egg emerges point first and laying usually takes 5–10 minutes.[29]

The eggs vary in colour and pattern to help the parents recognize them,[citation needed] each egg's pattern being unique. Colours include white, green, blue or brown with spots or speckles in black or lilac. After laying, the female will look at the egg before starting the first incubation shift.[29] Both parents incubate the egg for the 28 to 34 days to hatching in shifts of 1–38 hours.[17]

Eggs can be lost due to predation or carelessness. Crows and gulls are opportunist egg thieves. Eggs are also knocked from ledges during fights. If the first egg is lost, the female may lay a second egg. This egg is usually lighter than the first, with a lighter yolk.[citation needed] Chicks from second eggs grow quicker than those from first eggs. However this rapid growth comes at a cost, first chicks have larger fat reserves and can withstand temporary shortages of food.[citation needed]

Growth of the chick

Chicks occupy an intermediate position between the precocial chicks of genus Synthliboramphus and the semi-precocial chicks of the Atlantic puffin.[30] They are born downy and by 10 days old they are able to regulate their own temperature.[11] Except in times of food shortage there is at least one parent present at all times, and both parents are present 10–30% of the time.[31] Both parents alternate between brooding the chick or foraging for food.

Provisioning is usually divided equally between each parent, but unequal provisioning effort can lead to divorce.[27] Common murres are single-prey loaders, this means that they carry one fish at time. The fish is held lengthways in the adult's bill, with the fish's tail hanging from the end of the beak. The returning adult will form its wings into a 'tent' to protect the chick. The adult points its head downwards and the chick swallows the fish head first.

Alloparenting behaviour is frequently observed. Non-breeding and failed breeders show great interest in other chicks, and will attempt to brood or feed them. This activity is more common as the chicks get older and begin to explore their ledge. There has also been a record of a pair managing to raise two chicks.[32] Adults that have lost chicks or eggs will sometimes bring fish to the nest site and try to feed their imaginary chick.

At time of extreme food stress, the social activity of the breeding ledge can break down. On the Isle of May colony in 2007, food availability was low. Adults spent more of their time-budget foraging for their chicks and had to leave them unattended at times. Unattended chicks were attacked by breeding neighbour which often led to their deaths. Non-breeding and failed breeders continued to show alloparental care.[33]

The chicks will leave the nest after 16 to 30 days (average 20–22 days),[7] and glide down into the sea, slowing their fall by fluttering as they are not yet able to fly. Chicks glide from heights as high as 457 m (1,499 ft) to the water below.[citation needed] Once the young chick has left the nest, the male is in close attendance for up to two months. The chicks are able to fly roughly two weeks after fledging. Up until then the male feeds and cares for the chick at sea. In its migration south the chick swims about 1,000 km (620 mi). The female remains at the nest site for up to 36 days after the chick has fledged (average 16 days).[34]

Relationship to humans

Pollution

Major oil spills double the winter mortality of breeding adults but appear to have little effect on birds less than three years old.[35] This loss of breeding birds can be compensated by increased recruitment of 4–6 year olds to breeding colonies.[35]

Recreational disturbance

Nesting common murres are prone to two main sources of recreational disturbance: rock-climbing and birdwatching. Sea cliffs are a paradise for climbers as well as birds; a small island like Lundy has over 1000 described climbing routes.[36] To minimise disturbance, some cliffs are subject to seasonal climbing bans.[36]

Birdwatching has conflicting effects on common murres. Birdwatchers petitioned the UK government to introduce the Sea Birds Preservation Act 1869. This act was designed to reduce the effects of shooting and egg collecting during the breeding season.[37] Current concerns include managing the effect of visitor numbers at wildlife reserves. Common murres have been shown to be sensitive to visitor numbers.[38]

Seabirds as indicators of marine health

When common murres are feeding their young, they return with one fish at a time. The provisioning time relates to the distance of the feeding areas from the colony and the numbers of available fish. There is a strong non-linear relationship between fish density and colony attendance during chick-rearing.[39]

As a food source

In areas such as Newfoundland, the birds, along with the related thick-billed murre, are referred to as 'turrs' or 'tuirs', and are consumed. The meat is dark and quite oily, due to the birds' diet of fish. Eggs have also been harvested. Eggers from San Francisco took almost half a million eggs a year from the Farallon Islands in the mid-19th century to feed the growing city.[40]

Notes

- ^ a b Template:IUCN

- ^ Strauch (1985)

- ^ "Guillemot Uria aalge [Pontoppidan, 1763]". Bird facts. British Trust for Ornithology. Retrieved 20 August 2008.

- ^ "Guillemot". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ "Murre". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ a b c Mullarney et al. (1999)

- ^ a b Harris & Birkhead (1985)

- ^ CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses by John B. Dunning Jr. (Editor). CRC Press (1992), ISBN 978-0-8493-4258-5.

- ^ Blamire (2008)

- ^ a b Nettleship (1996)

- ^ a b Mahoney & Threlfall(1981)

- ^ Vaughn (1937)

- ^ Livezey (1988)

- ^ Bédard (1985)

- ^ Birkhead & Taylor (1977)

- ^ Piatt, John F.; Nettleship, David N. (April 1985). "Diving depths of four alcids" (PDF). The Auk. 102 (2): 293–297. doi:10.2307/4086771.

- ^ a b c d Gaston & Jones (1998)

- ^ Humphreys et al. (2007)

- ^ Mitchell et al. (2004)

- ^ A massive die-off

- ^ a b Lilliendahl et al. (2003)

- ^ Harris et al. (2008)

- ^ Harris et al. (2007)

- ^ a b Birkhead (1978)

- ^ a b c Lewis et al. (2007)

- ^ Kokko et al. (2004)

- ^ a b Moody et al. (2005)

- ^ Johnson (1941)

- ^ a b Harris & Wanless (2006)

- ^ Gaston (1985)

- ^ Wanless et al. (2005)

- ^ Harris et al. (2000)

- ^ Ashbrook et al. (2008)

- ^ Harris & Wanless (2003)

- ^ a b Votier et al. (2008)

- ^ a b Harrison (2008)

- ^ Barclay-Smith (1959)

- ^ Beale (2007)

- ^ Harding et al. (2007)

- ^ White, Peter; (1995)

References

- Ashbrook, Kate; Wanless, Sarah; Harris, Michael P.; Hamer, Keith C. (2008). "Hitting the buffers: Conspecific aggression undermines benefits of colonial breeding under adverse conditions". Biology Letters. 4 (6): 630–3. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2008.0417. PMC 2614172. PMID 18796390.

- Barclay-Smith, Phyllis (2008). "The British contribution to bird protection". Ibis. 101: 115. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1959.tb02363.x.

- Beale, Colin M. (2007). "Managing visitor access to seabird colonies: A spatial simulation and empirical observations". Ibis. 149: 102. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.2007.00640.x.

- Bédard, Jean (1985): Evolution and Characteristics of the Atlantic Alcidae in Nettleship and Birkhead (1985) pp 1–51

- Bennett, J. (2001): Animal Diversity Web – Uria aalge. Retrieved 2008-JAN-13.

- Birkhead, Tim R. (1978). "Behavioural adaptations to high density nesting in the Common Guillemot, Uria aalge". Animal Behaviour. 26: 321. doi:10.1016/0003-3472(78)90050-7.

- Birkhead, Tim R.; Taylor, Antony M. (2008). "Moult of the Guillemot Uria aalge". Ibis. 119: 80. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1977.tb02048.x.

- Blamire, Sheila (2008). "A yellow-billed Guillemot in Norway". Birding World. 21 (7): 306.

- Freethy, Ron (1987): The Auks: an ornithologist's guide. Facts on File, New York. ISBN 0-8160-1696-8

- Gaston, Anthony J. (1985): Development of the young in the Atlantic Alcidae in Nettleship & Birkhead (1985) pp 319–354

- Gaston, Anthony J. & Jones, Ian (1998) The Auks, Alcidae. Oxford University Press, Oxford. ISBN 0-19-854032-9

- Harding, Ann M.A.; Piatt, John F.; Schmutz, Joel A. (2007). "Seabird behavior as an indicator of food supplies: sensitivity across the breeding season". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 352: 269–274. doi:10.3354/meps07072.

- Harris, Michael P. & Birkhead, Tim R. (1985): Breeding Ecology of the Atlantic Alcidae in Nettleship & Birkhead (1985) pp 155–204

- Harris, Michael P.; Bull, J.; Wanless, Sarah (2000). "Common Guillemots Uria aalge successfully feed two chicks". Atlantic Seabirds. 2 (2): 92–94.

- Harris, Michael P.; Frederiksen, Morten; Wanless, Sarah (2007). "Within- and between-year variation in the juvenile survival of the Common Guillemot Uria aalge". Ibis. 149 (3): 472. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.2007.00667.x.

- Harris, Michael P.; Newell, Mark; Daunt, Francis; Speakman, John R.; Wanless, Sarah (2007). "Snake Pipefish Entelurus aequoreus are poor food for seabirds". Ibis. 150 (2): 413. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.2007.00780.x.

- Harris, Michael P.; Wanless, Sarah (2003). "Postfledging occupancy of breeding sites by female common murres (Uria aalge)". The Auk. 120: 75. doi:10.1642/0004-8038(2003)120[0075:POOBSB]2.0.CO;2.

- Harris, Michael P.; Wanless, Sarah (2006). "Laying a big e.g. on a little ledge:does it help a female Common Guillemot if Dad's there?". British Birds. 99: 230–235.

- Harrison, Paul (2008): Lundy (Climbers Club Guides) Climbers Club

- Harrison, Peter (1988): Seabirds (2nd ed.). Christopher Helm, London. ISBN 0-7470-1410-8

- Humphreys, Elizabeth M.; Wanless, Sarah; Bryant, David M. (2007). "Elevated metabolic costs while resting on water in a surface feeder: the Black-legged Kittiwake Rissa tridactyla". Ibis. 149: 106–111. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.2006.00618.x.

- Johnson, Robert A. (1941). "Nesting behavior of the Atlantic Murre". Auk. 58 (2): 153–163. doi:10.2307/4079099.

- Kokko, H.; Harris, Michael, P.; Wanless, Sarah (2004). "Competition for breeding sites and site-dependent population regulation in a highly colonial seabird, the common guillemot Uria aalge". Journal of Animal Ecology. 73 (2): 367. doi:10.1111/j.0021-8790.2004.00813.x.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Lewis, Sue; Roberts, Gilbert; Harris, Michael P.; Prigmore, Carina; Wanless, Sarah (2007). "Fitness increases with partner and neighbour allopreening". Biology Letters. 3 (4): 386–389. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0258. PMC 2390679. PMID 17550875.

- Lilliendahl, K.; Solmundsson, J.; Gudmundsson, G.A.; Taylor, L. (2003). "Can surveillance radar be used to monitor the foraging distribution of colonially breeding alcids?" (PDF). Condor. 105 (1): 145–150. doi:10.1650/0010-5422(2003)105[145:CSRBUT]2.0.CO;2.

- Livezey, Bradley C. (1988). "Morphometrics of Flightlessness in the Alcidae". Auk. 105 (4): 681–698. JSTOR 4087381.

- Mahoney, Shane P.; Threlfall, William (2008). "Notes on the eggs, embryos and chick growth of Common Guillemots Uria aalge in Newfoundland". Ibis. 123 (2): 211. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1981.tb00928.x.

- Mitchell, P. Ian; Newton, Stephen F.; Ratcliffe, Norman & Dunn, Timothy E. (eds.) (2004): Seabird Populations of Britain and Ireland. Poyser, London. ISBN 0-7136-6901-2

- Moody, Allison T.; Wilhelm, Sabina, I.; Cameron-MacMillan, Maureen L.; Walsh, Carolyn J.; Storey, Anne E. (2004). "Divorce in common murres (Uria aalge): relationship to parental quality". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 57 (3): 224. doi:10.1007/s00265-004-0856-8.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Mullarney, Killian; Svensson, Lars; Zetterström, Dan & Grant, Peter J. (1999): Collins Bird Guide: 194–197 HarperCollins, London. ISBN 0-00-711332-3

- National Geographic Society (2002): Field Guide to the Birds of North America. National Geographic, Washington DC. ISBN 0-7922-6877-6

- Nettleship, David N. (1996): 2. Common Murre. In: del Hoyo, Josep; Elliott, Andrew & Sargatal, Jordi (eds.) (1996), Handbook of Birds of the World (Volume 3: Hoatzin to Auks): 709–710, plate 59. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. ISBN 84-87334-20-2

- Nettleship, David, N. & Birkhead, Tim R. (eds.) (1985): The Atlantic Alcidae. Academic Press, London. ISBN 0-12-515671-5

- Sibley, David Allen (2000): The Sibley Guide to Birds. Alfred A. Knopf, New York. ISBN 0-679-45122-6

- Strauch, J.G. Jr. (1985). "The phylogeny of the Alcidae" (PDF). Auk. 102 (3): 520–539. JSTOR 4086647.

- Vaughn, H.R.H. (1937). "Flight speed of guillemots, razorbills and puffins" (PDF). British Birds. 31: 123.

- Votier, S.C.; Birkhead, T.R.; Oro, D.; Trinder, M.; Grantham, M.J.; Clark, J.A.; McCleery, R.H.; Hatchwell, B.J. (2008). "Recruitment and survival of immature seabirds in relation to oil spills and climate variability". Journal of Animal Ecology. 77 (5): 974–983. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2656.2008.01421.x. PMID 18624739.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Wanless, S.; Harris, M.P.; Redman, P.; Speakman, J.R. (2005). "Low energy values of fish as a probable cause of a major seabird breeding failure in the North Sea". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 294: 1–8. doi:10.3354/meps294001.

- White, Peter; (1995), The Farallon Islands, Sentinels of the Golden Gate, Scottwall Associates:San Francisco, ISBN 0-942087-10-0

External links

(Uria aalge).

- The RSPB: Guillemot

- BirdGuides: Guillemot (Uria aalge)

- Common Murre - Uria aalge - USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter

- Common Murre Restoration Project at San Francisco Bay NWR Complex

- Project Puffin: Common Murres

- Sheila Blamire – Norway Wildlife 2 Includes her photograph of an aberrant common guillemot with a yellow bill.

- "Common murre media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Common murre photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Interactive range map of Uria aalge at IUCN Red List maps

- IUCN Red List least concern species

- Uria

- Guillemots

- Arctic birds

- Atlantic auks

- Pacific auks

- Birds of the Aleutian Islands

- Birds of the British Isles

- Birds of Iceland

- Birds of Scandinavia

- Native birds of Eastern Canada

- Native birds of Western Canada

- Native birds of the Northwestern United States

- Animals described in 1763