Crop (anatomy)

A crop (sometimes also called a croup or a craw, or ingluvies) is a thin-walled expanded portion of the alimentary tract used for the storage of food prior to digestion. This anatomical structure is found in a wide variety of animals. It has been found in birds, some non-avian dinosaurs, and in invertebrate animals including gastropods (snails and slugs), earthworms,[1] leeches,[2] and insects.[3]

Bees

Cropping is used by bees to temporarily store nectar of flowers. When bees "suck" nectar, it is stored in their crops.[4]

Birds

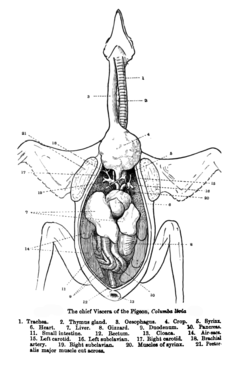

In a bird's digestive system, the crop is an expanded, muscular pouch near the gullet or throat. It is a part of the digestive tract, essentially an enlarged part of the oesophagus. As with most other organisms that have a crop, the crop is used to temporarily store food. Not all birds have a crop. In adult doves and pigeons, the crop can produce crop milk to feed newly hatched birds.[5]

Scavenging birds, such as vultures, will gorge themselves when prey is abundant, causing their crop to bulge. They subsequently sit, sleepy or half torpid, to digest their food.

Most raptors, including hawks, eagles and vultures (as stated above), have a crop; however, owls do not. Similarly, all true quail (Old World quail and New World quail) have a crop, but the Buttonquail or Turnicidae do not. While chickens and turkeys possess a crop, geese do not have one, a fact which occasioned what many consider Sherlock Holmes' — or rather author Arthur Conan Doyle's — greatest forensic blunder.[6]

See also

- Esophagus

- Proventriculus

- Gizzard

- Gular pouch, in bird anatomy, a flap generally used to store fish and other prey while hunting

References

- ^ "Worm World: About Earthworms". Retrieved 2008-12-16.

- ^ Sawyer, Roy T. "Leech Biology and Behaviour, Volume II" (PDF). Retrieved 2014-01-09.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Triplehorn, Charles A (2005). Borror and DeLong's introduction to the study of insects (7th ed. ed.). Australia: Thomson, Brooks/Cole. ISBN 9780030968358.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Honeybee Biology". 1994. Retrieved 2008-12-16.

- ^ Gordon John Larkman Ramel (2008-09-29). "The Alimentary Canal in Birds". Retrieved 2008-12-16.

- ^ Alfred Hickling. "Review: The New Annotated Sherlock Holmes edited by Leslie S Klinger | Books". The Guardian. Retrieved 2012-07-26.