DIAC

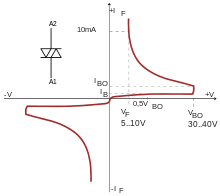

The DIAC is a diode that conducts electrical current only after its breakover voltage, VBO, has been reached momentarily. The term is an acronym of "diode for alternating current".

When breakdown occurs, the diode enters a region of negative dynamic resistance, leading to a decrease in the voltage drop across the diode and, usually, a sharp increase in current through the diode. The diode remains in conduction until the current through it drops below a value characteristic for the device, called the holding current, IH. Below this value, the diode switches back to its high-resistance, non-conducting state. This behavior is bidirectional, meaning typically the same for both directions of current.

Most DIACs have a three-layer structure with breakover voltage of approximately 30 V. Their behavior is similar to that of a neon lamp, but it can be more precisely controlled and takes place at a lower voltage.

DIACs have no gate electrode, unlike some other thyristors that they are commonly used to trigger, such as TRIACs. Some TRIACs, like Quadrac, contain a built-in DIAC in series with the TRIAC's gate terminal for this purpose.

DIACs are also called "symmetrical trigger diodes" due to the symmetry of their characteristic curve. Because DIACs are bidirectional devices, their terminals are not labeled as anode and cathode but as A1 and A2 or main teminal MT1 and MT2.

SIDAC

A Silicon Diode for Alternating Current (SIDAC) is a less commonly used device, electrically similar to the DIAC, but having, in general, a higher breakover voltage and greater current handling capacity.

The SIDAC is another member of the thyristor family. Also referred to as a SYDAC (Silicon thYristor for Alternating Current), bi-directional thyristor breakover diode, or more simply a bi-directional thyristor diode, it is technically specified as a bilateral voltage triggered switch. Its operation is similar to that of the DIAC, but SIDAC is always a five-layer device with low-voltage drop in latched conducting state, more like a voltage triggered TRIAC without a gate. In general, SIDACs have higher breakover voltages and current handling capacities than DIACs, so they can be directly used for switching and not just for triggering of another switching device.

The operation of the SIDAC is functionally similar to that of a spark gap, but is unable to reach its higher temperature ratings. The SIDAC remains nonconducting until the applied voltage meets or exceeds its rated breakover voltage. Once entering this conductive state going through the negative dynamic resistance region, the SIDAC continues to conduct, regardless of voltage, until the applied current falls below its rated holding current. At this point, the SIDAC returns to its initial nonconductive state to begin the cycle once again.

Somewhat uncommon in most electronics, the SIDAC is relegated to the status of a special purpose device. However, where part-counts are to be kept low, simple relaxation oscillators are needed, and when the voltages are too low for practical operation of a spark gap, the SIDAC is an indispensable component.

Similar devices, though usually not functionally interchangeable with SIDACs, are the Thyristor Surge Protection Devices (TSPD), Trisil, SIDACtor®, or the now-obsolete[when?] Surgector. These are designed to tolerate large surge currents for the suppression of overvoltage transients. In many applications this function is now served by metal oxide varistors (MOVs), particularly for trapping voltage transients on the power mains. .

See also

References

External links

- Strobe circuit containing a SIDAC

- What is a DIAC Description of the DIAC with its operation, applications, use with TRIAC, etc