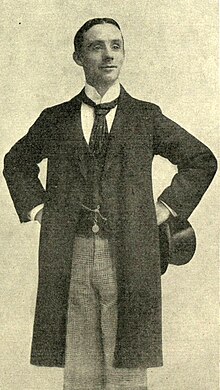

Dan Leno

Dan Leno (20 December 1860 – 31 October 1904), born George Wild Galvin, was a leading English music hall comedian and musical theatre actor during the late Victorian era. He was best known, aside from his music hall act, for his dame roles in the annual pantomimes that were popular at London's Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, from 1888 to 1904.

Leno was born in St Pancras, London, and began to entertain as a child. In 1864, he joined his parents on stage in their music hall act, and he made his first solo appearance, aged nine, at the Britannia Music Hall in Coventry. As a youth, he was famous for his clog dancing, and in his teen years, he became the star of his family's act. He adopted the stage name Dan Leno and, in 1884, made his first performance under that name in London. As a solo artist, he became increasingly popular during the late 1880s and 1890s, when he was one of the highest-paid comedians in the world. He developed a music hall act of talking about life's mundane subjects, mixed with comic songs and surreal observations, and created a host of mostly working-class characters to illustrate his stories. In 1901, still at the peak of his career, he performed his "Huntsman" sketch for Edward VII at Sandringham. The monarch was so impressed that Leno became publicly known as "the king's jester".

Leno also appeared in burlesque and, every year from 1888 to 1904, in the Drury Lane Theatre's Christmas pantomime spectacles. He was generous and active in charitable causes, especially to benefit performers in need. Leno continued to appear in musical comedies and his own music hall routines until 1902, although he suffered increasingly from alcoholism. This, together with his long association with dame and low comedy roles, prevented him from being taken seriously as a dramatic actor, and he was turned down for Shakespearean roles. Leno began to behave in an erratic and furious manner by 1902, and he suffered a mental breakdown in early 1903. He was committed to a mental asylum, but was discharged later that year. After one more show, his health declined, and he died aged 43.

Biography

Family background and early life

Leno was born in St Pancras, London. He was the youngest of six children, including two elder brothers, John and Henry, and an elder sister, Frances. Two other siblings died in infancy.[1] His parents, John Galvin (1826–1864) and his wife Louisa, née Dutton (1831–1891), performed together in a music hall double act called "The Singing and Acting Duettists". They were known professionally as Mr. and Mrs. Johnny Wild.[2] They were not very successful, and the family struggled in poverty.[3][n 1]

Having had very little schooling, and being raised by performers, Leno learned to entertain as a child.[3] In 1862, Leno's parents and elder brothers appeared at the Surrey Music Hall in Sheffield, then performed in northern cities later in the year.[5] In 1864, at the age of four, Leno joined his parents on stage for the first time, at the Cosmotheca Music Hall in Paddington, under the billing "Little George, the Infant Wonder, Contortionist, and Posturer".[3][6]

When Leno was still four, his father, an alcoholic, died at the age of 37. The family moved to Liverpool a few months later, where his mother married William Grant (1837–1896),[7] on 7 March 1866.[8] Grant was a comedian of Lancastrian and Irish descent, who performed in music halls throughout the British provinces under the stage name of William Leno.[3][9] He was a seasoned actor and had previously been employed by Charles Kean in his theatre company at the Princess's Theatre in London.[10] In 1866, the family home in Marylebone was demolished to make way for St Pancras railway station[11] and, as a result, Leno's sister Frances was sent to live with an uncle, while his brother John, who performed occasionally with his parents, took full-time employment.[3] Leno, his mother, stepfather and brother Henry moved north and settled in Liverpool, where they performed in various halls and theatres, including the Star Music Hall, but often returned to London to perform in the capital's music halls.[3][9]

Early career

In 1865, Leno and his brother Henry, who first taught Leno to dance, formed a clog dancing double act known as "The Great Little Lenos". This was the first time that Leno used his stepfather's stage name, "Leno", which he never registered legally.[12] The same year, Leno also appeared in his first pantomime, in Liverpool, where he had a supporting part as a juvenile clown in Fortunatus; or, The Magic Wishing Cap alongside his parents, who appeared as "Mr and Mrs Leno – Comic Duettists".[13] On 18 July 1866, Leno, Henry and their parents appeared on the opening night of the Cambridge Music Hall in Toxteth, Liverpool, under the billing "Mr. and Mrs. Leno, the Great, Sensational, Dramatic and Comic Duettists and The Brothers Leno, Lancashire Clog, Boot and Pump Dancers".[14] The following year, the brothers made their first appearance without their parents at the Britannia music hall in Hoxton.[3] Although initially successful, the pair would experience many bouts of unemployment and often busked outside London pubs to make a living.[12] Tired of surviving on little or no money, Henry left the clog dancing act to take up a trade in London, forcing Leno to consider a future as a solo performer. Henry later founded a dance school.[n 2] Soon, however, Henry was replaced intermittently in the act by the boys' uncle, Johnny Danvers, who was a week older than Leno.[12][n 3] Leno and Danvers were close from an early age.[16]

Leno made his debut as a solo performer in 1869, returning to the Britannia music hall in Hoxton, where he became known as "The Great Little Leno, the Quintessence of Irish Comedians".[n 4] The name was suggested by his stepfather, William, who thought the Irish connection would appeal to audiences on their upcoming visit to Dublin.[15] Arriving in Ireland the same year, the Lenos were struggling financially and stayed with William's relatives. In addition to his performances as part of the family act, young Leno appeared as a solo act under an Irish-sounding stage name, "Dan Patrick".[1] This allowed him to earn a separate fee of 23 shillings per performance plus living expenses.[15] The name "Dan" was chosen to honour Dan Lowery, a northern music hall comedian and music hall proprietor whom the Lenos had met a few months earlier.[17] During this tour of Ireland, the Lenos appeared in Dublin in a pantomime written by Leno's father: Old King Humpty; or, Harlequin Emerald Isle and Katty of Killarney (1869), in which Leno received praise from Charles Dickens, who was in the audience and told him: "Good little man, you'll make headway!"[18]

In 1870, the Lenos appeared in another pantomime by Leno's father, Jack the Giant Killer; or, Harlequin Grim Gosling, or the Good Fairy Queen of the Golden Pine Grove, in which Leno played the title character and also featured in the variety entertainment that preceded the pantomime. This was his last theatrical role until 1886.[19] Throughout the 1870s, Leno and his parents performed as "The Comic Trio (Mr. & Mrs. Leno and Dan Patrick) In Their Really Funny Entertainments, Songs and Dances".[1] In the family act with his parents and Danvers, young Leno often took the leading role in such sketches as his stepfather's The Wicklow Wedding. Another of their sketches was Torpedo Bill, in which Leno played the title role, an inventor of explosive devices. His parents played a "washerwoman" and a "comic cobbler".[15] This was followed by another sketch, Pongo the Monkey.[20] Opening at Pullan's Theatre of Varieties in Bradford on 20 May 1878, this burlesque featured Leno as an escaped monkey; it became his favourite sketch of the period.[15]

The teenage Leno's growing popularity led to bookings at, among others, the Varieties Theatre in Sheffield and the Star Music Hall in Manchester.[21] At the same time, Leno's clog dancing continued to be so good that in 1880 he won the world championship at the Princess's Music Hall in Leeds,[1] for which he received a gold and silver belt weighing 44.5 oz (1.26 kg).[6][9] His biographer, the pantomime librettist J. Hickory Wood, described his act: "He danced on the stage; he danced on a pedestal; he danced on a slab of slate; he was encored over and over again; but throughout his performance, he never uttered a word".[22]

1880s

In 1878, Leno and his family moved to Manchester.[23] There, he met Lydia Reynolds, who, in 1883, joined the Leno family theatre company, which already consisted of his parents, Danvers and Leno. The following year, Leno and Reynolds married; around this time, he adopted the stage name "Dan Leno".[23] On 10 March 1884, the Leno family took over the running of the Grand Varieties Theatre in Sheffield.[24] The Lenos felt comfortable with their working class Sheffield audiences. On their opening night, over 4,000 patrons entered the theatre, paying sixpence to see Dan Leno star in Doctor Cut 'Em Up. In October 1884, facing tough competition, the Lenos gave up the lease on the theatre.[25]

In 1885, Leno and his wife moved to Clapham Park, London, and Leno gained new success with a solo act that featured comedy patter, dancing and song.[23] On the night of his London debut, he appeared in three music halls: the Foresters' Music Hall in Mile End, Middlesex Music Hall in Drury Lane and Gatti's-in-the-Road, where he earned £5 a week in total (£682 in 2024 adjusted for inflation).[26][27] Although billed as "The Great Irish Comic Vocalist and Clog Champion" at first, he slowly phased out his dancing in favour of character studies, such as "Going to Buy Milk for the Twins",[9] "When Rafferty Raffled his Watch" and "The Railway Guard".[1] His dancing had earned him popularity in the provinces, but Leno found that his London audiences preferred these sketches and his comic songs.[6][28] Leno's other London venues in the late 1880s included the Collins Music Hall in Islington, the Queen's Theatre in Poplar and the Standard in Pimlico.[29]

Leno was a replacement in the role of Leontes in the 1888 musical burlesque of the ancient Greek character Atalanta at the Strand Theatre, directed by Charles Hawtrey.[30] It was written by Hawtrey's brother, George P. Hawtrey, and it starred Frank Wyatt, Willie Warde and William Hawtrey.[31] The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News praised Leno's singing and dancing and reported that: "He brings a good deal of fun and quaintness to the not very important part of Leontes."[32] Leno accepted the role at short notice, with no opportunity to learn the script. But his improvised comedy helped to extend the life of the show. When Leno and another leading actor left a few months later, the production closed.[33]

Music hall

During the 1890s, Leno was the leading performer on the music hall stage, rivalled only by Albert Chevalier, who moved into music hall from the legitimate theatre.[34][35] Their styles and appeal were very different: Leno's characters were gritty working-class realists, while Chevalier's were overflowing in romanticism, and his act depicted an affluent point of view. The two represented the opposite poles of cockney comedy.[34][n 5]

For his music hall acts, Leno created characters that were based on observations about life in London, including shopwalkers, grocer's assistants, beefeaters, huntsmen, racegoers, firemen, fathers, henpecked husbands, garrulous wives, pantomime dames, a police officer, a Spanish bandit, a fireman and a hairdresser.[1] One such character was Mrs. Kelly, a gossip. Leno would sing a verse of a song, then begin a monologue, often his You know Mrs. Kelly? routine, which became a well-known catchphrase: "You see we had a row once, and it was all through Mrs. Kelly. You know Mrs. Kelly, of course. ... Oh, you must know Mrs. Kelly; everybody knows Mrs. Kelly."[6][37][38]

For his London acts, Leno purchased songs from the foremost music hall writers and composers. One such composer was Harry King, who wrote many of Leno's early successes.[39] Other well-known composers of the day who supplied Leno with numbers included Harry Dacre and Joseph Tabrar.[39] From 1890, Leno commissioned George Le Brunn to compose the incidental music to many of his songs, including "The Detective", "My Old Man", "Chimney on Fire", "The Fasting Man", "The Jap", "All Through A Little Piece of Bacon" and "The Detective Camera".[39] Le Brunn also provided the incidental music for three of Leno's best-known songs that depicted life in everyday occupations: "The Railway Guard" (1890), "The Shopwalker" and "The Waiter" (both from 1891).[40] The songs in each piece became instantly distinctive and familiar to Leno's audiences, but his occasional changes to the characterisations kept the sketches fresh and topical.[41]

"The Railway Guard" featured Leno in a mad characterisation of a railway station guard dressed in an ill-fitting uniform, with an unkempt beard and a whistle. The character was created by exaggerating the behaviour that Leno saw in a real employee at Brixton station who concerned himself in other people's business while, at the same time, not doing any work.[42] "The Shopwalker" was full of comic one-liners and was heavily influenced by pantomime. Leno played the part of a shop assistant, again of manic demeanour, enticing imaginary clientele into the shop before launching into a frantic selling technique sung in verse.[43] Leno's depiction of "The Waiter", dressed in an over-sized dinner jacket and loose-fitting white dickey, which would flap up and hit his face, was of a man consumed in self-pity and indignation. Overworked, overwrought and overwhelmed by the number of his customers, the waiter gave out excuses for the bad service faster than the customers could complain:[43][38]

Yes, sir! No, sir! Yes, sir! When I first came here these trousers were knee-breeches. Legs worn down by waiting. Sir! What did you say? How long would your steak be? Oh, about four inches I should say, about four inches. No, sir! sorry sir. Can't take it back now, sir. You've stuck your fork in and let the steam out!

Pantomime

Leno's first London appearance in pantomime was as Dame Durden in Jack and the Beanstalk, which he performed at London's Surrey Theatre in 1886, having been spotted singing "Going to Buy Milk" by the Surrey Theatre manager, George Conquest.[44] Conquest also hired Leno's wife to star in the production.[45] The pantomime was a success, and Leno received rave reviews; as a result, he was booked to star as Tinpanz the Tinker in the following year's pantomime, which had the unique title of Sinbad and the Little Old Man of the Sea; or, The Tinker, the Tailor, the Soldier, the Sailor, Apothecary, Ploughboy, Gentleman Thief.[45]

After these pantomime performances proved popular with audiences, Leno was hired in 1888 by Augustus Harris, manager at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, to appear in that year's Christmas pantomime, Babes in the Wood.[46] Harris's pantomime productions at the huge theatre were known for their extravagance and splendour. Each one had a cast of over a hundred performers, ballet dancers, acrobats, marionettes and animals, and included an elaborate transformation scene and an energetic harlequinade. Often they were partly written by Harris.[47][48] Herbert Campbell and Harry Nicholls starred with Leno in the next fifteen Christmas productions at Drury Lane. Campbell had appeared in the theatre's previous five pantomimes and was a favourite of the writer of those productions, E. L. Blanchard. Blanchard left the theatre when Leno was hired, believing that music hall performers were unsuitable for his Christmas pantomimes.[46] This was not a view shared by audiences or the critics, one of whom wrote:

I am inclined to think "the cake" for frolicsome humour is taken by the dapper new-comer, Mr. Dan Leno, who is sketched as the galvanic baroness in the wonderfully amusing dance which sets the house in a roar. The substantial "babes", Mr. Herbert Campbell and Mr. Harry Nicholls, would have no excuse if they did not vie in drollery with the light footed Dan Leno.[49]

Babes in the Wood was a triumph: the theatre reported record attendance, and the run was extended until 27 April 1889.[50] Leno considerably reduced his music-hall engagements as a consequence.[50][51] Nevertheless, between April and October 1889, Leno appeared simultaneously at the Empire Theatre and the Oxford Music Hall, performing his one-man show.[51] By this time, Leno was much in demand and had bookings for the next three years. On 9 May 1889 he starred for George P. Hawtrey in a matinee of Penelope, a musical version of a famous farce The Area Belle, to benefit the Holborn Lodge for Shop Girls. In this benefit, he played the role of Pitcher opposite the seasoned Gilbert and Sullivan performer Rutland Barrington.[51] The Times considered that his performance treated the piece "too much in the manner of pantomime".[52] During Leno's long association with the Drury Lane pantomimes, he appeared chiefly as the dame.[53] After Harris died in 1896, Arthur Collins became manager of the theatre and oversaw (and often helped to write) the pantomimes.[50]

In their pantomimes, the diminutive Leno and the massive Campbell were a visually comic duo.[54] They would often deviate from the script, improvising freely. This was met with some scepticism by producers, who feared that the scenes would not be funny to audiences and observed that, in any event, they were rarely at their best until a few nights after opening.[1] George Bernard Shaw wrote of one appearance: "I hope I never again have to endure anything more dismally futile",[55] and the English essayist and caricaturist Max Beerbohm stated that "Leno does not do himself justice collaborating with the public". He noted, however, that Leno "was exceptional in giving each of his dames a personality of her own, from extravagant queen to artless gossip".[56] In Sleeping Beauty, Leno and Campbell caused the audience to laugh even when they could not see them: they would arrive on stage in closed palanquins and exchange the lines, "Have you anything to do this afternoon, my dear?" – "No, I have nothing on", before being carried off again.[1] Leno and Campbell's pantomimes from 1889 were Jack and the Beanstalk (1889 and 1899), Beauty and the Beast (1890 and 1900), Humpty Dumpty (1891 and 1903), Little Bo-peep (1892), Robinson Crusoe (1893), Dick Whittington and His Cat (1894), Cinderella (1895), Aladdin (1896), The Babes in the Wood (1897) and the Forty Thieves (1898).[57]

Leno considered the dame roles in two of his last pantomimes, Bluebeard (1901) and Mother Goose (1902), written by J. Hickory Wood, to be his favourites. He was paid £200 (£27,426 in 2024 adjusted for inflation)[26] for each of the pantomime seasons.[58][59] Leno appeared at Drury Lane as Sister Anne in Bluebeard, a character described by Wood as "a sprightly, somewhat below middle aged person who was of a coming on disposition and who had not yet abandoned hope"[60] The Times drama critic noted: "It is a quite peculiar and original Sister Anne, who dances breakdowns and sings strange ballads to a still stranger harp and plays ping-pong with a frying-pan and potatoes and burlesques Sherlock Holmes and wears the oddest of garments and dresses her hair like Miss Morleena Kenwigs, and speaks in a piping voice – in short it is none other than Dan Leno whom we all know".[61] Mother Goose provided Leno with one of the most challenging roles of his career, in which he was required to portray the same woman in several different guises. Wood's idea, that neither fortune nor beauty would bring happiness, was illustrated by a series of magical character transformations.[62] The poor, unkempt and generally ugly Mother Goose eventually became a rich and beautiful but tasteless parvenu, searching for a suitor. The production was one of Drury Lane's most successful pantomimes, running until 28 March 1903.[62]

Later career

In 1896, the impresario Milton Bode approached Leno with a proposal for a farcical musical comedy vehicle devised for him called Orlando Dando, the Volunteer, by Basil Hood with music by Walter Slaughter. Leno's agent declined the offer, as his client was solidly booked for two years. Bode offered Leno £625 (£116,081 in 2024 adjusted for inflation)[26] for a six-week appearance in 1898. Upon hearing this, the comedian overrode his agent and accepted the offer.[63] Leno toured the provinces in the piece and was an immediate success. So popular was his performance that Bode re-engaged him for a further two shows: the musical farce In Gay Piccadilly! (1899), by George R. Sims, in which Leno's uncle, Johnny Danvers appeared (The Era said that Leno was "attracting huge houses" and called him "excruciatingly funny");[64] and the musical comedy Mr. Wix of Wickham (1902). Both toured after their original runs.[63][65][66] In 1897, Leno went to America and made his debut on 12 April of that year at Hammerstein's Olympia Music Hall on Broadway, where he was billed as "The Funniest Man On Earth". Reviews were mixed: one newspaper reported that the house roared its approval, while another complained that Leno's English humour was out of date.[67] His American engagement came to an end a month later, and Leno said that it was "the crown of my career".[68] Despite his jubilation, Leno was conscious of the few negative reviews he had received and rejected all later offers to tour the United States and Australia.[68]

The same year, the comedian lent his name and writing talents to Dan Leno's Comic Journal. The paper was primarily aimed at young adults and featured a mythologised version of Leno – the first comic paper to take its name from, and base a central character on, a living person. Published by C. Arthur Pearson, Issue No. 1 appeared on 26 February 1898, and the paper sold 350,000 copies a year.[63] Leno wrote most of the paper's comic stories and jokes, and Tom Browne contributed many of the illustrations.[69] The comedian retained editorial control of the paper, deciding which items to omit.[70] The Journal was known for its slogans, including "One Touch of Leno Makes the Whole World Grin" and "Won't wash clothes but will mangle melancholy". The cover always showed a caricature of Leno and his editorial staff at work and play. Inside, the features included "Daniel's Diary", "Moans from the Martyr", two yarns, a couple of dozen cartoons and "Leno's Latest – Fresh Jokes and Wheezes Made on the Premises".[71] After a run of nearly two years the novelty wore off, and Leno lost interest. The paper shut down on 2 December 1899.[69][70]

A journalist wrote, in the late 1890s, that Leno was "probably the highest paid funny man in the world".[72] In 1898, Leno, Herbert Campbell and Johnny Danvers formed a consortium to build the Granville Theatre in Fulham, which was demolished in 1971.[73] Leno published an autobiography, Dan Leno: Hys Booke, in 1899, ghostwritten by T. C. Elder.[9] Leno's biographer J. Hickory Wood commented: "I can honestly say that I never saw him absolutely at rest. He was always doing something, and had something else to do afterwards; or he had just been somewhere, was going somewhere else, and had several other appointments to follow."[74] That year, Leno performed the role of "waxi omo" (a slang expression for a black-face performer)[75] in the Doo-da-Day Minstrels, an act that included Danvers, Campbell, Bransby Williams, Joe Elvin and Eugene Stratton. The troupe's only performance was at the London Pavilion on 29 May 1899 as part of a benefit. Leno's song "The Funny Little Nigger" greatly amused the audience. His biographer Barry Anthony considered the performance to be "more or less, the last gasp of black-face minstrelsy in Britain".[75]

Between 1901 and 1903, Leno recorded more than twenty-five songs and monologues on the Gramophone and Typewriter Company label.[76] He also made 14 short films towards the end of his life, in which he portrayed a bumbling buffoon who struggles to carry out everyday tasks, such as riding a bicycle or opening a bottle of champagne.[77] On 26 November 1901, Leno, along with Seymour Hicks and his wife, the actress Ellaline Terriss, was invited to Sandringham House to take part in a Royal Command Performance to entertain King Edward VII, Queen Alexandra, their son George and his wife, Mary, the Prince and Princess of Wales. Leno performed a thirty-five minute solo act that included two of his best-known songs: "How to Buy a House" and "The Huntsman". After the performance, Leno reported, "The King, the Queen and the Prince of Wales all very kindly shook hands with me and told me how much they had enjoyed it. The Princess of Wales was just going to shake hands with me, when she looked at my face, and couldn't do it for some time, because she laughed so much. I wasn't intending to look funny – I was really trying to look dignified and courtly; but I suppose I couldn't help myself."[78][79] As a memento, the king presented Leno with a jewel-encrusted royal tie pin, and thereafter, Leno became known as "the King's Jester". Leno was the first music hall performer to give a Royal Command Performance during the king's reign.[78][80]

Personal life

In 1883, Leno met Sarah Lydia Reynolds (1866–1942), a young dancer and comedy singer from Birmingham, while both were appearing at King Ohmy's Circus of Varieties, Rochdale.[81] The daughter of a stage carpenter,[82] Lydia, as she was known professionally, was already an accomplished actress as a teenager: of her performance in Sinbad the Sailor in 1881, one critic wrote that she "played Zorlida very well for a young artiste. She is well known at this theatre and with proper training will prove a very clever actress."[83] She and Leno married in 1884 in a discreet ceremony at St. George's Church, in Hulme, Manchester, soon after the birth of their first daughter, Georgina.[84] A second child died in infancy,[85] and John was born in 1888.[1] Their three youngest children – Ernest (b. 1889), Sidney (b. 1891) and May (b. 1896) – all followed their father onto the stage. Sidney later performed as Dan Leno, Jr.[86] After Leno's mother and stepfather retired from performing, Leno supported them financially until their deaths.[87]

Leno owned 2 acres (8,100 m2) of land at the back of his house in Clapham Park, and was self-sufficient, producing cabbages, potatoes, poultry, butter and eggs. He would also send these as gifts to friends and family at Christmas.[88] In 1898, Leno and his family moved to 56 Akerman Road, Lambeth, where they lived for several years. A blue plaque was erected there in 1962 by the London County Council.[89]

Charity and fundraising

The Terriers Association was established in 1890 to help retired artists in need of financial help. Leno was an active fundraiser in this and in the Music Hall Benevolent Fund, of which he became President.[1] He was an early member of the entertainment charity Grand Order of Water Rats, which helps performers who are in financial need, and served as its leader, the King Rat, in 1891, 1892 and 1897.[35] Near the end of his life, Leno co-founded The Music Hall Artistes Railway Association, which entered a partnership with the Water Rats to form music hall's first trade union.[90] Some of Leno's charity was discreet and unpublicised.[91]

In the late 1890s, Leno formed a cricket team called the "Dainties", for which he recruited many of the day's leading comedians and music hall stars.[92] They played for charity against a variety of amateur teams willing to put up with their comedic mayhem, such as London's Metropolitan Police Force; Leno's and his teammates' tomfoolery on the green amused the large crowds that they drew.[93][94] From 1898 to 1903, the Dainties continued to play matches across London. Two films of action from the matches were produced in 1900 for audiences of the new medium of cinema. In September 1901, at a major charity match, the press noted the carnival atmosphere. The comedians wore silly costumes – Leno was dressed as an undertaker and later as a schoolgirl riding a camel. Bands played, and clowns circulated through the crowd. The rival team of professional Surrey cricketers were persuaded to wear tall hats during the match. 18,000 spectators attended, contributing funds for music hall and cricketers' charities, among others.[94][95]

Decline and mental breakdown

Leno began to drink heavily after performances, and, by 1901, like his father and stepfather before him, he had become an alcoholic.[1] He gradually declined physically and mentally and displayed frequent bouts of erratic behaviour that began to affect his work.[96] By 1902, Leno's angry and violent behaviour directed at fellow cast members, friends and family had become frequent. Once composed, he would become remorseful and apologetic.[96] His erratic behaviour was often a result of his diminishing ability to remember his lines and inaudibility in performance.[1] Leno also suffered increasing deafness, which eventually caused problems on and off stage. In 1901, during a production of Bluebeard, Leno missed his verbal cue and, as a result, was left stuck up a tower for more than twenty minutes. At the end of the run of Mother Goose in 1903, producer Arthur Collins gave a tribute to Leno and presented him, on behalf of the Drury Lane Theatre's management, with an expensive silver dinner service. Leno rose to his feet and said: "Governor, it's a magnificent present! I congratulate you and you deserve it!"[96]

Frustrated at not being accepted as a serious actor, Leno became obsessed with the idea of playing Richard III and other great Shakespearean roles, inundating the actor–manager Herbert Beerbohm Tree with his proposals.[1] After his final run of Mother Goose at the Drury Lane Theatre in early 1903, Leno's delusions overwhelmed him. On the closing evening, and again soon afterwards, he travelled to the home of Constance Collier, who was Beerbohm Tree's leading lady at His Majesty's Theatre, and also followed her to rehearsal there.[97] He attempted to persuade her to act alongside him in a Shakespearean season that Leno was willing to fund. On the second visit to her home, Leno brought Collier a jewellery box holding a diamond-encrusted plaque. Recognising that Leno was having a mental breakdown, she sadly and gently refused his offer, and Leno left distraught.[97]

Two days later, he was admitted into an asylum for the insane.[98] Leno spent several months in Camberwell House Asylum, London, under the care of Dr. Savage, who treated Leno with "peace and quiet and a little water colouring".[99] On his second day, Leno told a nurse that the clock was wrong. When she stated that it was right, Leno remarked, "Well if it's right, then what's it doing here?" Leno made several attempts to leave the asylum, twice being successful. He was found each time and promptly returned.[100]

Last year and death

Upon Leno's release from the institution in October 1903, the press offered much welcoming commentary and speculated as to whether he would appear that year in the Drury Lane's pantomime, scheduled to be Humpty Dumpty. Concerned that Leno might suffer a relapse, Arthur Collins employed Marie Lloyd to take his place.[101] By the time of rehearsals, however, Leno persuaded Collins that he was well enough to take part, and the cast was reshuffled to accommodate him. Leno appeared with success. Upon hearing his signature song, the audience reportedly gave him a standing ovation that lasted five minutes.[102] He received a telegram from the King congratulating him on his performance.[103] Leno's stage partner Herbert Campbell died in July 1904, shortly after the pantomime, following an accident at the age of fifty-seven. The death affected Leno deeply, and he went into a decline. At that time, he was appearing at the London Pavilion, but the show had to be cancelled owing to his inability to remember his lines.[96] So harsh were the critics that Leno wrote a statement, published in The Era, to defend the show's originality.[104] On 20 October 1904, Leno gave his last performance in the show. Afterwards, he stopped at the Belgrave Hospital for Children in Kennington to leave a donation of £625 (£84,773 in 2024 adjusted for inflation).[26][105]

Leno died at his home in London on 31 October 1904, aged 43, and was buried at Lambeth cemetery, Tooting.[106][107] The cause of death is not known.[n 6] His death and funeral were national news. The Daily Telegraph wrote in its obituary: "There was only one Dan. His methods were inimitable; his face was indeed his fortune ... Who has seen him in any of his disguises and has failed to laugh?"[108] Max Beerbohm later said of Leno's death: "So little and frail a lantern could not long harbour so big a flame".[109] His memorial is maintained by the Grand Order of Water Rats, which commissioned the restoration of his grave in 2004.[110][n 7]

Notes and references

- Notes

- ^ Louisa and John married at St. John's Church, Waterloo, London, on 2 January 1850 and lived in Ann Street, near Waterloo. John was born in Middlesex, and Louisa was born in Worthing in Sussex. John's father was Maurice Galvin, an Irish bricklayer. Louisa's father, Richard Dutton, was an artist, who ended up as a patient in the Middlesex Pauper Lunatic Asylum.[4]

- ^ The dance school was advertised as: "Clog dancing taught by H. Wild, Brother and Tutor of Dan Leno, J. H. Haslam, etc."[15]

- ^ Born in Sheffield, Danvers moved to Glasgow as a boy and later became a "silver plater".[16]

- ^ Comedian, here, refers to a performer of comic songs.[12]

- ^ Chevalier wrote all his own songs, while Leno bought songs from established song writers and composers.[34][36]

- ^ No medical records survive. At least three theories for the cause of death have been given by various sources: The New York Times stated he had died of heart disease "Dan Leno Dead", 1 November 1904. The Oxford Dictionary National Biography, on the other hand, states that he died of tertiary syphilis.[1] Finally, his biographer Gyles Brandreth claimed that Leno had succumbed to a brain tumour, which Brandreth thought would help explain his erratic behaviour. Leno stated in 1904: "the cause of my brain trouble was attributed to a fall off my bicycle".[79]

- ^ Arthur Roberts, a close friend, commented after Leno's death: "It seems an extraordinary thing to say, but I really believe that King Edward's kindness was the unconscious means of hastening Dan Leno's mind over the borderline of insanity ... Poor Dan had been fluttering outside the cage of the madhouse for some years, and the great honour and dignity which he received at the hands of the King just tilted the scales of divine injustice. He went inside".[80]

- References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Hogg, James. "Leno, Dan", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, accessed November 2011 (subscription required)

- ^ Brandreth, p. 1

- ^ a b c d e f g Brandreth, p. 2

- ^ Anthony, pp. 5–7

- ^ Anthony, pp. 12–13

- ^ a b c d "Biography of Dan Leno", Victoria and Albert Museum website, accessed 20 January 2012

- ^ Anthony, pp. 15 and 92

- ^ Anthony, p. 16

- ^ a b c d e Leno, Dan. Dan Leno: Hys Booke, Greening & Co. (1901), accessed 19 November 2011

- ^ The Era, 12 February 1860. Records show William Leno appearing as Clown in Harlequin and the Yellow Dwarf at the Theatre Royal, South Shields.

- ^ "History and Restoration", Stpancras.com, accessed 28 March 2012

- ^ a b c d Brandreth, p. 3

- ^ Anthony, p. 16

- ^ Anthony, p. 17

- ^ a b c d e Brandreth, p. 4

- ^ a b Anthony, p. 33

- ^ Anthony, p. 31

- ^ Brandreth, p. 12

- ^ Anthony, pp. 22–71

- ^ Wood, pp. 83–84

- ^ Brandreth, p. 20

- ^ Wood, p. 13

- ^ a b c Brandreth, p. 22

- ^ Anthony, pp. 45–47. Sheffield's Lyceum Theatre was built on the site in 1897. See Anthony, p. 54

- ^ Anthony, p. 53

- ^ a b c d UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved May 7, 2024.

- ^ Brandreth, p. 23

- ^ Wood, p. 14

- ^ Brandreth, p. 24

- ^ Leeds Times, 3 November 1888, p. 6

- ^ "Tonight's Entertainment", Pall Mall Gazette, 11 December 1888, p. 12

- ^ Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, 30 November 1888, p. 24

- ^ Anthony, p. 86

- ^ a b c Anthony, p. 97

- ^ a b "King Rat Dan Leno", History: Grand Order of Water Rats, Gowr.net, accessed 17 November 2011

- ^ Booth (1944), p. 53

- ^ Partridge, p. 563

- ^ a b Short, pp. 47–48

- ^ a b c Anthony, p. 100

- ^ Anthony, p. 101

- ^ Anthony, p. 106

- ^ Anthony, p. 103

- ^ a b Anthony, p. 105

- ^ Brandreth, p. 26

- ^ a b Brandreth, p. 27

- ^ a b Anthony, p. 88

- ^ "Mr. Pitcher's Art", Obituary, The Times, 3 March 1925

- ^ Anthony, p. 87

- ^ Penny Illustrated Paper, 5 January 1887, pp. 12–13

- ^ a b c Brandreth, p. 28

- ^ a b c Anthony, p. 90

- ^ The Times, 10 May 1889, p. 30

- ^ Disher, p. 56

- ^ Shaw, G. B. Saturday Review, 1897, edition 83, pp. 87–89

- ^ Brandreth, p. 45

- ^ Beerbohm, p. 350

- ^ Anthony, pp. 215–216

- ^ "Dan Leno's Salary", Manchester Evening News, 27 December 1901, p. 5

- ^ Anthony, p. 190

- ^ Wood, p. 33

- ^ The Times, 27 December 1901, p. 4

- ^ a b Anthony, p. 191

- ^ a b c Brandreth, p. 69

- ^ "Amusements in Birmingham: Grand Theatre", The Era, 11 November 1899, p. 23a

- ^ "Dan Leno at The Theatre Royal", Sheffield Independent, 31 October 1899, p. 11

- ^ Booth (1996), p. 203; the latter musical was revived on Broadway in 1904 with many of the songs composed or re-set with new music by the young Jerome Kern.

- ^ Brandreth, p. 64

- ^ a b Brandreth, p. 66

- ^ a b Anthony, p. 170

- ^ a b Brandreth, p. 70

- ^ Brandreth, pp. 69–70

- ^ Blumenfeld, p. 167

- ^ "From the Archives: The Granville Theatre", Hammersmith and Fulham News, 6 October 2009, p. 66

- ^ Wood, p. 277

- ^ a b Anthony, p. 71

- ^ Brandreth, pp. 96–97

- ^ Flanders, Judith. "1901 census", Who Do You Think You Are magazine, accessed 27 June 2013

- ^ a b "Actors at Sandringham", The New York Times, 1 December 1901, p. 7

- ^ a b Brandreth, p. 80

- ^ a b Brandreth, p. 81

- ^ "Dan Leno's Widow", Hull Daily Mail, 30 April 1942, p. 4

- ^ Anthony, p. 43

- ^ The Stage, 20 May 1881, p. 44

- ^ Anthony, pp. 53–54

- ^ Anthony, p. 96

- ^ Anthony, p. 200

- ^ Wood, p. 99

- ^ Blumenfeld, p. 166

- ^ "Leno, Dan (1860–1904)", Blue Plaques, English Heritage on line, accessed 28 March 2012

- ^ Anthony, p. 120

- ^ Anthony, p. 121

- ^ "Dan Leno's Cricketers", Sheffield Evening Telegraph, 20 June 1899, p. 4

- ^ "Dan Leno and His Cricket Team", Illustrated Police News, 8 October 1898, p. 3

- ^ a b Williamson, Martin. "Lions, camels and clowns at The Oval", ESPN Cricinfo online, 18 October 2008, accessed 16 February 2012

- ^ "Dan Leno's Cricket", Falkirk Herald, 24 June 1899, p. 6

- ^ a b c d Brandreth, p. 84

- ^ a b Anthony, pp. 192–193

- ^ Brandreth, pp. 85–89

- ^ " Dan Leno Improving", Evening Telegraph, 24 July 1903, p. 2

- ^ Brandreth, p. 89

- ^ "Dan Leno's Successor", Evening Telegraph, 24 July 1903, p. 3

- ^ Brandreth, p. 90

- ^ "The King and Dan Leno", Manchester Evening News, 28 December 1903, p. 2

- ^ "Mr Dan Leno. Pavillion, where I am singing Two New Songs of my own, copied from no one. The "Boy" song, which an unkind critic compared to another, I beg to say I wrote and Sang in Glasgow Thirty-one years ago. Who is copying now? All my Thirty-four Minutes' Gags are copied from no one." "Dan Leno", The Era, 22 October 1904, p. 7

- ^ Anthony, p. 197

- ^ Brandreth, p. 91

- ^ "Death of Dan Leno", Western Times, 1 November 1904, p. 5

- ^ "Obituary", Daily Telegraph, 1 November 1904, p. 2

- ^ Beerbohm, p. 349

- ^ Anthony, p. 10

Sources

- Anthony, Barry (2010). The King's Jester. London: I. B. Taurus & Co. ISBN 978-1-84885-430-7.

- Beerbohm, Max (1954). Around Theatres. London: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-246-63509-9.

- Blumenfeld, R. D. (1930). RDB's Diary 1887–1914. London: Heinemann. OCLC 68136714.

- Booth, J. B. (1944). The Days We Knew. London: T. W. Laurie. OCLC 4238609.

- Booth, Michael (1996). The Edwardian Theatre: Essays on Performance and the Stage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52145-375-2.

- Brandreth, Gyles (1977). The Funniest Man on Earth: The Story of Dan Leno. London: Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 978-0-241-89810-9.

- Disher, M.W. (1942). Fairs, Circuses and Music Halls. London: William Collins. OCLC 604161468.

- Leno, Dan (1901). Hys Booke. London: Greening and Co. OCLC 467629.

- Partridge, Eric (1986). A Dictionary of Catchphrases. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-05916-9.

- Short, Henry, Ernest (1938). Ring Up the Curtain: Being a Pageant of English Entertainment Covering Half a Century. London: Ayer. OCLC 1411533.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Wood, Hickory, J. (1905). Dan Leno. London: Methuen. ISBN 978-0-217-81849-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- Dan Leno at IMDb

- Dan Leno profile and recordings of "The Huntsman" (1901) and "Going To The Races" (1903)

- The legacy of Dan Leno at Ward's Book of Days

- Lions, camels, and clowns at the oval: 1901 ... one of cricket's most unusual matches

- Photo of the young Leno at the Victoria & Albert Museum website

- Photo of Leno's "Champion Clog Dancers Belt" at the Victoria & Albert Museum website

- Books by/about Dan Leno at Internet Archive (scanned books)