Hugo Black

Hugo LaFayette Black (February 27, 1886 – September 25, 1971) was a Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States (1937 - 1971). He is noted for his advocacy of a "literal" reading of the United States Constitution, and for his advocacy of the position that the guarantees of liberties in the U.S. Bill of Rights were imposed on the states via their incorporation in the Fourteenth Amendment. His jurisprudence has been the focus of much discussion. Because of his insistence on a strict textual analysis of Constitutional issues, as opposed to the process-oriented jurisprudence of many of his colleagues, it is difficult to characterize Black as a "liberal" or a "conservative" as those terms are generally understood. Yet his theory of "incorporation" often translated into support for strengthening civil liberties. In the 1920's, Black (like Chief Justice Edward Douglass White) was a member of the Ku Klux Klan, and in 1921 he defended Klansmen accused of the murder of priest James Coyle. However, he later publicly disavowed the Klan, and his record on the Supreme Court bench clearly demonstrates strong anti-racism and support for the Civil Rights Movement.

Early years

Hugo LaFayette Black was born on February 27, 1886 in a small wooden farmhouse in Harlan, Alabama, a rural town in Clay County, Alabama. Harlan was a poor, isolated community in the Appalachian foothills.

Because his brother Orlando had become a medical doctor, Hugo decided to follow in his footsteps and at age 17 he left school in Ashland (where he had been whipped and beaten by the principal) and enrolled in the 1902-1903 term at Birmingham Medical School. However, it was his brother Orlando who suggested that Hugo should enroll in the University of Alabama to study law.

After graduating in June 1906 he moved back to Ashland and established a legal practice above a grocery shop. Black joined a Baptist church and applied for membership in the Freemasons. His legal practice was not a success and a year and a half after his law office on the first floor had opened, the entire building burned to the ground. Black then moved back to Birmingham in 1907 to continue his law practice, where at age 21 he was also initiated as a member of a Masonic lodge.

Following his involvement with a case involving the defense of an African-American who had been forced into a form of commercial slavery following incarceration, Hugo Black was befriended by a judge connected with the case. That same judge was later appointed as one of three Commissioners for the City of Birmingham; he asked Hugo Black to serve as the City Recorder (Police Court Judge.) Black's experience as a police court judge was his only judicial experience prior to his Supreme Court appointment.

On October 21, 1912 Black left the bench when he resigned as Recorder and returned to his full time legal practice. On December 1, 1914 after his election to a four-year term, he became the Prosecuting Attorney for Jefferson County, just seven years after leaving what he termed "Hillbilly Clay County".

On August 3, 1917 he resigned his elected office and joined the Officers Training School at Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia. On November 3 Captain Black was assigned for duty to the 81st Field Artillery Unit near Chattanooga, Tennessee, a short distance from Oglethorpe. He was a soldier until September 20, 1918 "and never fired a shot against the nation's enemy." He returned to private law practice in Birmingham.

Marriage

On February 23, 1921 he married Josephine Foster and had three children: Hugo, Jr., who was born in 1922; Sterling Foster, born in 1924 and Martha Josephine who born in 1933. They remained married until she died after a long illness on December 6, 1951. He later remarried the former Elizabeth Seay DeMeritte. Following his first marriage Black resumed his practice of law with an attorney who became head of the Ku Klux Klan in Alabama.

Stephenson Trial

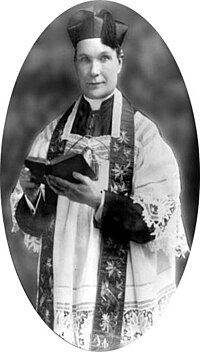

On August 11 of that same year, Black was asked to defend the Reverend Edwin R. Stephenson, a Ku Klux Klan member who had been accused of shooting to death Father James Coyle, leader of the large Catholic community at Saint Paul's Church in Birmingham. Stephenson was both a barber and a minister who added to his income by marrying couples at the Jefferson County Courthouse where he was known as the "marrying parson". In the previous two years he had married 1,140 couples, almost half of them in the courthouse.

Ruth Stephenson was Edwin's eighteen-year old daughter who had run away from home and become a Catholic. On August 11 she asked Father Coyle to perform her marriage to a Hispanic male from Puerto Rico named Pedro Gussman so that she would become independent of her parents. Gussman was a Catholic by faith and a paper hanger by trade; he had decorated the Stephenson home.

Edwin Stephenson knew of his daughter's conversion to Catholicism and of her romance with Pedro, but not of the marriage. Stephenson confronted Coyle at Saint Paul's who then informed Stephenson of the marriage.

According to Black's defense, Stephenson hurled racist abuse at Coyle who responded with his fists and then Stephenson shot him, following which he wandered back to the courthouse and asked the sheriff to jail him.

The presiding judge and several members of the courtroom staff were active Klan members and they helped to ensure that several members of the KKK were selected to jury service. Black is reported to have communicated with the Klansmen on the jury through the organization's hand signals in order to secure a verdict of not guilty for his client, but there is no clear documentation of this fact. According to page 87 of the biography by Roger K. Newman, no official records of this trial exist and their destruction is attributed to the power and influence of members of the Ku Klux Klan at that time.

Ku Klux Klan controversy

In the 1920s, the Ku Klux Klan, revived after a half-century of dormancy due to the release of The Birth of a Nation, became a dominant force in Alabama politics, as it did in several Northern states as well as the national Democratic Party, with its anti-black and anti-Catholic rhetoric. In those years there were as many as 85,000 members of the Ku Klux Klan in Alabama and the organization often wielded substantial influence in the state's elections.

On September 11, 1923 Black became a member of the Robert E. Lee Klan No. 1 of the Ku Klux Klan in Birmingham. He claimed that he remained in the KKK for only two years until 1925, during which time he alleged that he attended a maximum of no more than four meetings, and then he tendered a friendly resignation. However, in 1926 he not only attended a State Convention of the KKK, but he chose to address the delegates as well. Hugo Black is alleged to have said that what he liked about the Klan was "not the burning crosses ... not attempting to regulate anybody," but for keeping the door open "to the boy that comes up on the humble hillside, or in the lowly valley." The full text of this speech appeared 14 years later in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette on September 15, 1937, in page two and in column two.

According to the New York Times of November 26, 1926, page 15 and column 3, the Grand Dragon of Klan was the Assistant Attorney General of Alabama. The paper later reported that KKK members occupied city, county and state offices. According to the published version of the Hugo Black Symposium on pages 78-79 it is reported that:

Some of those who knew him (Black) offered additional reasons for his joining. Herman Beck, a leading Jewish merchant in Birmingham encouraged his young friend Black to become a Klansman so that he could help contain the trouble-making element just coming to the fore of the organization in Alabama.

Black resigned from the Klan the day before he announced his intention to seek election to the United States Senate and he did so under cloudy circumstances. According to page 103 of the biography of Black by Roger K. Newman (see details below), his resignation was contrived. (The Klan did not endorse Hugo Black and the KKK backed another candidate: New York Times, August 12, 1926, page 1, column 5.)

Election to U.S. Senate

In 1926 Black won his seat in the Senate, which he then retained for another eleven years. In the Senate during 1934 he headed a committee to investigate an event known as the Air Mail Scandal and as a result he drafted the 'Air Mail Act of 1934', which changed the nature of the American airline industry.

Black was a staunch supporter of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal. Black also supported Roosevelt's unsuccessful 1937 attempt to change the composition of the Supreme Court via the Court-packing Bill.

US Supreme Court Justice

Black was nominated by President Roosevelt to the Supreme Court in 1937 to replace Justice Willis Van Devanter. His nomination aroused controversy due to his previous affiliation with the Ku Klux Klan. However, he was confirmed by the Senate and was sworn in on August 19, 1937.

In the summer following his confirmation, the KKK controversy was rekindled due to a report by an investigative journalist. Public opinion was inflamed, and Black was obliged to deliver a radio address in which he disavowed the Klan and stated that he was not racist, anti-Semitic, or anti-Catholic.

On the bench Justice Black began to arouse interest by filing a continuing series of lengthy dissenting opinions. In 1940 Justice Black delivered the opinion of the Court in Chambers v. Florida, 309 US 227, in which four African-Americans who had been coerced by the police into making confessions to murder. His decision in favor of the defendants helped to underline the message of his broadcast in which he had disassociated himself from racism. In 1948 he joined in the Court's decision in Shelley v. Kraemer which invalidated judicial enforcement of a racial restriction on the sale of land. In 1954 he joined the unanimous decision in Brown v. Board of Education which proclaimed the end of de jure racial segregation in US public schools.

Constitutional theories

Black believed that the first eight amendments to the United States Constitution, which were originally intended to be amendments to the federal constitution of the United States of America, had become applicable to the individual States by the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment, and specifically the Privileges or Immunities Clause of Section 1 of that amendment. This view was very controversial and was vigorously challenged among proponents of federalism, including justices Felix Frankfurter and John Marshall Harlan II who insisted that Black's view was contrary to the original intention of the framers of the Fourteenth Amendment. Hugo Black began to seriously push his viewpoint via a long appendix attached to his dissent in Adamson v. California in 1947, which argued that the framers of the Fourteenth Amendment intended to make the Bill of Rights applicable to the states. His debate between Black and his critics remains unresolved and controversial, with conservative scholars such as Raoul Berger siding with Frankfurter and Harlan.

Black's views attracted the support of Justice William O. Douglas but were in a distinct minority on the Supreme Court. Most of the justices held the belief that the Fourteenth Amendment incorporated some provisions of the Bill of Rights but not others. Frankfurter believed that the Fourteenth Amendment incorporated none of the Bill of Rights but only substantively prohibited government actions that "shock the conscience" or are "inherent in the concept of ordered liberty," as had been held in 1938's Palko v. Connecticut.

While Black's position that the Bill of Rights had been incorporated against the states attracted some support, however, his view that the substantive meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment is limited to incorporating the Bill of Rights was adopted by no other justice. Thus, Black was the lone dissenter in 1971's In Re Winship, which declared that the Due Process Clause imposed on the prosecution a burden of proof beyond a reasonable doubt in criminal cases.

During the anti-Communist McCarthy era of the 1950s, Black became known as a defender of First Amendment rights, perhaps most notably in his dissent in Dennis v. United States, 341 US 494 during 1951. By the end of Black's term, however, he had become disenchanted with what he considered the vulgarity of the counterculture and dissented from the Court's decision in 1971's Cohen v. California which held that a person could not be punished for wearing a jacket emblazoned with the words "Fuck the Draft."

He took a dim view of government entanglement with religious practice, and he wrote the Court's ground-breaking opinion on school prayer in the 1962 case of Engel v. Vitale.

Black wrote the unanimous opinion handed down in 1963's Gideon v. Wainwright, which guaranteed the right of all defendants to be represented by an attorney in state criminal trials. This had been the result of a decade-long crusade by Black after the Court ruled in Betts v. Brady that counsel was required only in state criminal trials involving "special needs" on the part of defendants.

Black was noted for his consistent adherence to the theory that the text of the Constitution is absolutely determinative on any question calling for judicial interpretation. No other justice has adopted quite so dogmatic a view of the Constitution's text, leading to Black's reputation as a "strict constructionist."

Thus, Black refused to join in the efforts of the justices on the Court who sought to abolish capital punishment in the United States, which efforts succeeded (temporarily) in the term immediately following Black's death; Black claimed that the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendment's reference to takings of "life" meant approval of the death penalty was implicit in the Bill of Rights. He also was not persuaded that a right of privacy was implicit in the Ninth Amendment, and dissented from the Court's 1965 Griswold v. Connecticut decision which invalidated a conviction for the sale of banned contraceptives. Black claimed that there was no "right of privacy" in the text of the Constitution.

Although Black maintained his commitment to racial equality throughout his tenure on the Court, he voted to uphold the constitutionality of state-imposed poll taxes which, though nominally race-neutral, had a disparate impact on African-American voters. The key to Black's position in all of these cases was that there was no specific constitutional provision which restrained the governmental actions complained of.

Resignation and death

Black resigned from the Court on September 17, 1971. He died eight days after resigning. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery. President Nixon appointed Lewis F. Powell to fill the vacant seat.

Tributes

In 1987, the new courthouse building for the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Alabama in Birmingham, Alabama was designated the "Hugo L. Black United States Courthouse."

Template:Start U.S. Supreme Court composition Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1937–1938 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1938 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1939 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1940–1941 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition CJ Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1941–1942 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1943–1945 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1945–1946 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition CJ Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1946–1949 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1949–1953 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition CJ Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1953-1954 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1955-1956 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1956-1957 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1957-1958 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1958-1962 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1962-1965 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1965-1967 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1967-1969 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition CJ Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1969 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1970-1971 Template:End U.S. Supreme Court composition