Enlargement of the eurozone

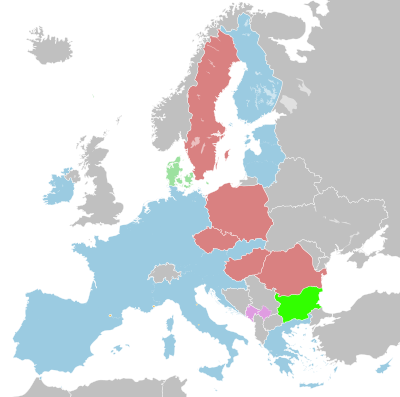

The enlargement of the eurozone is an ongoing process within the European Union (EU). All member states of the EU, except for Denmark, the United Kingdom and de facto Sweden, are obliged to adopt the euro as their sole currency when they meet the criteria. This includes two years in the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM II) and keeping inflation inline with the EU average.

Eleven EU states were part of the initial introduction in 1999. Greece joined in 2001 before the coins and notes were released and the other national currencies were retired. Slovenia joined the Eurozone on 1 January 2007, Cyprus and Malta joined on 1 January 2008, Slovakia joined on 1 January 2009,[1] and Estonia joined the eurozone on 1 January 2011.[2]

Of the remaining states on the agenda, the earliest expected accession is in 2014. Denmark is not obliged to join, but a referendum on the abolition of the opt-out from eurozone membership has been debated. Should the country decide to do so it may join the euro rapidly, as Denmark is already part of the ERM II. The United Kingdom and Sweden are outside of the ERM II.

Accession criteria

In order to join the eurozone officially, (thus being able to mint coins separately), a country must first be a member of the European Union, and then meet certain economic criteria, including accession to ERM II, which fixes the acceding country's national currency's exchange rate to the euro, within a specified band (normally ±15%).

European microstates that have monetary agreements with acceding countries can continue these agreements to mint separate coins on the accession of the larger state, but do not get a say in the economic affairs of the eurozone. This has been used to allow Monaco, San Marino and the Vatican City to mint their own coins, and Andorra is negotiating a similar agreement.

In 2009 the International Monetary Fund (IMF) suggested that countries should be allowed to "partially adopt" the euro, which would allow them to use the euro but would not give them a seat on the European Central Bank.[3]

| Country | HICP inflation rate[4][nb 1] | Excessive deficit procedure[5] | Exchange rate | Long-term interest rate[6][nb 2] | Compatibility of legislation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Budget deficit to GDP[7] | Debt-to-GDP ratio[8] | ERM II member[9] | Change in rate[10][11][nb 3] | ||||

| Reference values[nb 4] | Max. 3.3%[nb 5] (as of May 2024) |

None open (as of 19 June 2024) | Min. 2 years (as of 19 June 2024) |

Max. ±15%[nb 6] (for 2023) |

Max. 4.8%[nb 5] (as of May 2024) |

Yes[12][13] (as of 27 March 2024) | |

| Max. 3.0% (Fiscal year 2023)[12] |

Max. 60% (Fiscal year 2023)[12] | ||||||

| 5.1% | None | 3 years, 11 months | 0.0% | 4.0% | Yes | ||

| 1.9% | 23.1% | ||||||

| 6.3% | None | No | 2.3% | 4.2% | No | ||

| 3.7% (exempt) | 44.0% | ||||||

| 1.1% | None | 25 years, 5 months | 0.2% | 2.6% | Unknown | ||

| -3.1% (surplus) | 29.3% | ||||||

| 8.4% | None | No | 2.4% | 6.8% | No | ||

| 6.7% | 73.5% | ||||||

| 6.1% | None | No | 3.1% | 5.6% | No | ||

| 5.1% | 49.6% | ||||||

| 7.6% | Open | No | -0.3% | 6.4% | No | ||

| 6.6% | 48.8% | ||||||

| 3.6% | None | No | -8.0% | 2.5% | No | ||

| 0.6% | 31.2% | ||||||

- Notes

- ^ The rate of increase of the 12-month average HICP over the prior 12-month average must be no more than 1.5% larger than the unweighted arithmetic average of the similar HICP inflation rates in the 3 EU member states with the lowest HICP inflation. If any of these 3 states have a HICP rate significantly below the similarly averaged HICP rate for the eurozone (which according to ECB practice means more than 2% below), and if this low HICP rate has been primarily caused by exceptional circumstances (i.e. severe wage cuts or a strong recession), then such a state is not included in the calculation of the reference value and is replaced by the EU state with the fourth lowest HICP rate.

- ^ The arithmetic average of the annual yield of 10-year government bonds as of the end of the past 12 months must be no more than 2.0% larger than the unweighted arithmetic average of the bond yields in the 3 EU member states with the lowest HICP inflation. If any of these states have bond yields which are significantly larger than the similarly averaged yield for the eurozone (which according to previous ECB reports means more than 2% above) and at the same time does not have complete funding access to financial markets (which is the case for as long as a government receives bailout funds), then such a state is not to be included in the calculation of the reference value.

- ^ The change in the annual average exchange rate against the euro.

- ^ Reference values from the Convergence Report of June 2024.[12]

- ^ a b Belgium, Denmark, and the Netherlands were the reference states.[12]

- ^ The maximum allowed change in rate is ± 2.25% for Denmark.

Historical enlargements

The first enlargement, Greece, took place on 1 January 2001; before the euro entered its physical form in 2002, but after its formal creation in 1999. The first post-2002 enlargements were to the states who joined in 2004. First Slovenia, replacing the Slovenian tolar on 1 January 2007, then Cyprus and Malta on 1 January 2008. On 1 January 2009 Slovakia exchanged its koruna for the euro and on 1 January 2011 Estonia similarly exchanged its kroon for the euro.

The new EU members which joined bloc during the fifth enlargement wave (2004–2007) are all obliged to adopt the euro under the terms of their accession treaties, however in September 2011, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and Romania said the euro zone they thought they were going to join, a monetary union, may very well end up being a very different union entailing much closer fiscal, economic and political convergence. "All seven countries agree to state that a change in the euro zone's legal status could change the conditions of their adhesion treaties," which "could force them to stage new referenda" on euro take-up, said a diplomatic source close to the talks to AFP.[17]

ERM II members

| Non-eurozone member state | Currency (Code) |

Central rate per €1[18] | EU join date | ERM II join date[18] | Government policy on euro adoption | Convergence criteria compliance[19] (as of June 2024) |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lev (BGN) |

1.95583[nb 1] | 2007-01-01 | 2020-07-10 | Euro adoption on 1 July 2025[21] | Compliant with 4 out of 5 criteria (all except inflation)[22] | The Bulgarian government expects to be in compliance with all criteria by the end of 2024[22] | |

| Koruna (CZK) |

Free floating | 2004-05-01 | None | Assessment of joining ERM-II to be completed by October 2024[23] | Compliant with 2 out of 5 criteria | ||

| Krone (DKK) |

7.46038 | 1973-01-01 | 1999-01-01 | Not on government's agenda[24][25] | Not assessed due to opt-out from eurozone membership | Rejected euro adoption by referendum in 2000 | |

| Forint (HUF) |

Free floating | 2004-05-01 | None | Not on government's agenda[26] | Not compliant with any of the 5 criteria | ||

| Złoty (PLN) |

Free floating | 2004-05-01 | None | Not on government's agenda[27] | Not compliant with any of the 5 criteria | ||

| Leu (RON) |

Free floating | 2007-01-01 | None | ERM-II by 2026 and euro by 1 January 2029[28][29][30] | Not compliant with any of the 5 criteria | ||

| Krona (SEK) |

Free floating | 1995-01-01 | None | Not on government's agenda[31] | Compliant with 2 out of 5 criteria | Rejected euro adoption by referendum in 2003. Still obliged to adopt the euro once compliant with all criteria.[nb 2] |

Apart from Denmark and the United Kingdom, which have opt-outs under the Maastricht Treaty, all other EU members are legally obliged to join the eurozone. The following members have acceded to ERM II, in which they must spend two years, before they can adopt the euro.

Denmark

Denmark has pegged its krone to the euro (€1 = DKK 7.46038 ± 2.25%) and the krone remains in the ERM. In December 1992 Denmark negotiated a number of opt-out clauses from the Maastricht treaty via the Edinburgh Agreement, including not adopting the euro as currency. This was done in response to the Maastricht treaty having been rejected by the Danish people in a referendum earlier that year. As a result of the changes, the treaty was finally ratified in a subsequent referendum held in 1993. On 28 September 2000, another referendum was held in Denmark regarding the euro resulting in a 53.2% vote against joining.

On 22 November 2007, the newly re-elected Danish government declared its intention to hold a new referendum on the abolishment of the four opt-out clauses, including on the euro, by 2011.[32] Several polls have been done each year; in 2008 and 2009 they generally but did not always show support among the Danes for adopting the euro.

The economic crisis has also led to a debate within the Faroe Islands, an autonomous Danish dependency outside the EU, about whether the islands should adopt the currency along the lines of other non-EU euro users, as previously they would have maintained their currency if Denmark adopted the euro.[33][34][35]

Latvia

Latvia has been a member of the European Union since 1 May 2004 and is a member of the Economic and Monetary Union of the European Union. Its currency, the Latvian lats, is in ERM II, and floats within 1% of the central rate, Ls 0.702804 = €1. Latvia had originally planned to adopt the euro on 1 January 2008 but this has been put back several times[36][37] but after being elected in 2011, Latvian President Andris Bērziņš aims for his country to join in 2014: "Personally I'm very optimistic we'll join the euro on 1 January 2014. It's our goal and we are working hard to implement this process."[38]

Lithuania

The Lithuanian litas is part of ERM II and in practice it is pegged to the euro at a rate of 3.45280 litai = €1. Lithuania originally set 1 January 2007 as the target date for joining the euro, but their application was rejected by the European Commission because inflation was slightly higher (0.1%) than the permitted maximum. In December 2006 the government approved a new convergence plan which, whilst reaffirming that the government wanted to join the eurozone "as soon as possible", said that expected inflation increases in 2007–8 would mean the best period for joining the euro would be 2010 or after.[39] In December 2007, Prime Minister Gediminas Kirkilas said Lithuania would be able to join in 2010–11, but increasing inflation in 2008 led banking analysts to put back the expected date to 2013 at the earliest.[40][41] By the time of the 2010 European sovereign debt crisis, the expected date had been put further back to 2014.[42]

Lithuania has expressed interest in a suggestion from the IMF that countries who aren't able to meet the Maastricht criteria are able to "partially adopt" the euro, using the currency but not getting a seat at the European Central Bank.[3]

Obliged to join

The following members must first join ERM II before they can adopt the euro:

Bulgaria

The lev is not part of ERM II, but has been pegged to the euro since its launch (€1 = BGN 1.95583). It was previously pegged on a par to the German Mark. Hence, Bulgaria already fulfilled the great majority of the EMU membership criteria and must, from 2009, comply with the Maastricht criteria to join the eurozone in 2012, the tentative deadline set by Finance Minister Plamen Oresharski.[43]

While the currency board which pegs Bulgaria to the euro has been seen as beneficial to the country fulfilling EMU criteria so early,[44] the ECB has been pressuring Bulgaria to drop it as it did not know how to let a country using a currency board join the euro.[clarification needed] The Prime Minister has stated the desire to keep the currency board until the euro was adopted. However, factors such as a high inflation, an unrealistic exchange rate with the euro and the country's low productivity are negatively affected by the system.[45]

Bulgaria meets three and fails on one of the criteria in order to join the eurozone. It derogates on the price stability criterion, which envisages that its inflation does not exceed that of the three EU member states with the lowest inflation (Malta, the Netherlands and Denmark) by more than 1.5%. Bulgaria’s inflation in the 12 months to March 2008 reached 9.4%, well above the reference value of 3.2%, the report said.

On the upside, Bulgaria fulfills the state budget criterion, which foresees that the deficit does not exceed 3% of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP). Over the past few years, the report said, the country has consistently improved its budget fundamentals and since 2003, a break-even point, the budget ran surpluses and in 2007 was at 3.4% of GDP. The EC forecasts that it will remain at 3.2% of GDP in both 2008 and 2009.

In regard to public debt, Bulgaria has also been within the prescribed cap of up to 60% of GDP. Government debt has also been declining consistently, from 50% of GDP to 18% in 2007. The expectation is to reach 11% of GDP in 2009.[46]

Bulgaria was expected to enter ERM II in November 2009,[47] but that target date has been moved. On 22 December 2009 Simeon Dyankov, Bulgaria's finance minister, said that the country would apply to join the ERM II in March 2010, [48] but due to a high deficit Bulgaria won't apply to join the ERM II mechanism in 2010.[49]

A recent analysis says that Bulgaria will not be able to join the Eurozone earlier than 2015, due to the high inflation and the repercussions of the global financial crisis of 2008.[50]

Czech Republic

The Czech Republic is bound by the Treaty of Accession 2003 to join the euro at some point, but this is not likely to come soon. The koruna is not part of ERM II. Since joining the EU in 2004, the Czech Republic has adopted a fiscal and monetary policy that aims to align its macroeconomic conditions with the rest of the European Union. Currently, the most pressing issue is the large Czech fiscal deficit. Originally, the Czech Republic aimed for entry into the ERM II in 2008 or 2009, but the current government has officially dropped the 2010 target date, saying it will clearly not meet the economic criteria.

Although the country is economically better positioned than other EU Members to join the euro, it is not expected before 2015 due to the political reluctance in this subject.[51] Finance Minister of the interim government, Eduard Janota, said in Brussels in January 2010 that it was unrealistic for the Czech Republic to adopt the euro in 2015 without a profound public finance reform.[52] Central bank governor Zdeněk Tůma even speculated about 2019.[53] The debt crisis in the eurozone decreased interest in the Czech Republic towards it.[54]

In late 2010 a discussion arose within the Czech government about negotiating an opt-out from joining the Eurozone. This discussion was partially initiated by Euro-sceptic Czech President Václav Klaus. Czech Prime Minister Petr Nečas later stated that no opt-out is needed because Czech Republic can't be forced to join the ERM II mechanism and therefore will itself decide when or if to fulfill one of the obligatory criteria to join the Eurozone, which is approach very similar to the one of Sweden. Nečas also stated that his cabinet will not decide upon the joining during its term which is due to expire in 2014 and Czech Republic therefore will not be able to become a member of the Eurozone sooner than in 2017.[55][56]

Hungary

Hungary originally hoped to adopt the euro by 1 January 2010. Most financial studies, such as those produced by Standard & Poor's and by Fitch Ratings, suggested that Hungary would be unable to adopt the common European currency on schedule, due to the country's high deficit, which in 2006 exceeded 10% of the GDP. The deficit fell below 5% of GDP in 2007, and was expected to be 3.8% at the end of 2008.

According to Reuters, central bank Governor András Simor expected to sit down with the government in the first half of 2009 "to discuss euro adoption". In 2009, Hungary's finance minister said that Hungary may start talks on joining ERM II near the end of 2009, and enter the Eurozone in 2013–2014 at the earliest.[57]

Poland

Poland is bound by the Treaty of Accession 2003 to join the euro at some point, but current indications are that this will not be for several years to come as economic criteria must be met. The złoty is not part of ERM II, itself a requirement for euro membership.

The Finance Minister Dominik Radziwill said on 10 July 2009 that Poland could enter the Eurozone in 2014, meeting the fiscal criteria in 2012.[58] In 2010, the eurozone's debt crisis caused Poles' interest to cool, with nearly half of the population opposed to entry.[54] However in December 2011 Polish foreign minister Radosław Sikorski said that Poland could join the euro before 2016 as long as "the eurozone is reformed by then and the entrance is beneficial to us."[59] As of 2012, 60% of Poles are opposed to adopting the common currency.[60]

Romania

Romania is scheduled to replace the current national currency, the Romanian leu, with the euro once Romania fulfils the convergence criteria. The euro is scheduled to be adopted by Romania in 2015.[61] According to the Romanian government, it will not be able to join the European Exchange Rate Mechanism before 2013–2014.[62]

Sweden

According to the 1994 accession treaty,[63] approved by referendum (52% in favour of the treaty), Sweden is required to join the euro if, at some point, the convergence criteria are fulfilled. However, on 14 September 2003, 56% of Swedes voted against adopting the euro in a second referendum.[64] The Swedish government has argued that staying outside the euro is legal since one of the requirements for eurozone membership is a prior two-year membership of the ERM II; by simply choosing to stay outside the exchange rate mechanism, the Swedish government is provided a formal loophole avoiding the requirement of adopting the euro. Most of Sweden's major parties continue to believe that it would be in the national interest to join, but they have all pledged to abide by the result of the referendum for the time being and show no interest in raising the issue.

The parties seem to agree that Sweden would not adopt the euro until after a second referendum. Prime Minister Fredrik Reinfeldt stated in December 2007 that there will be no referendum until there is stable support in the polls.[65] The polls have generally showed stable support for the "no" alternative, except some polls in 2009 showing a support for "yes". In 2010 the polls showed strong support for "no" again.

Not obliged to join

Denmark

Denmark is not obliged to join but is an ERM II member. Read more about Denmark under the ERM II members headline.

United Kingdom

The British currency is the pound sterling and the country has an opt-out from eurozone membership. The Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government elected in 2010 has pledged not to join the euro during its term of office,[66] due to expire in 2015.

The United Kingdom redesigned most of its coinage in 2008. The German newspaper Der Spiegel saw this as an indication that the country has no intention of switching to the euro within the foreseeable future.[67] In December 2008, José Barroso, the President of the European Commission, told French radio that some British politicians were considering the move because of the effects of the global credit crisis; the office of the Prime Minister, Gordon Brown, denied that there was any such change in official policy.[68] In February 2009, Monetary Policy Affairs Commissioner Joaquin Almunia said "The chance that the British pound sterling will join: high."[69]

The Sovereign Base Areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia introduced the euro at the same time as Cyprus, on 1 January 2008. Previously, they used the Cypriot Pound. They do not have separate euro coins.

Outside the EU

Andorra

Andorra is currently making de facto use of the euro. In 2011 Andorra and the EU signed a monetary agreement. Subject to ratification of the agreement and fulfillment of several additional conditions related to money laundering, terrorist financing and other financial issues,[70] Andorra will be an official Eurozone member and mint its own coins as of 1 July 2013.

Croatia

Croatia is expected to become a member of the EU on 1 July 2013.[71] Croatia would then be obliged to eventually adopt the euro. In 2006, Croatia fulfilled the convergence criteria (inflation 2.6%, budget balance −3.0%, public debt 56.2%), however Croatia would still have to spend two years in ERM II after it acceded.

Iceland

Due to instability in the Icelandic króna there has been discussion in Iceland about adopting the euro. However, according to Jürgen Stark, a Member of the Executive Board of the European Central Bank, "Iceland would not be able to adopt the EU currency without first becoming a member of the EU".[72] Iceland has since applied for EU membership.

Iceland has a problem with the convergence criteria, from 2008 and on[citation needed]. Inflation 10–15% (2008–2009), budget deficit 24 Bn ISK, 6.9% of GNP, government debt 1400 Bn ISK (estimate end 2009, 400% of GNP).[73][74][75] There are hopes for improvements, much lower estimated inflation in 2010, but debt will remain a problem.

New Caledonia, French Polynesia and Wallis and Futuna

The French overseas collectivities French Polynesia and Wallis and Futuna have declared themselves in favour of joining the eurozone, replacing the CFP franc with the euro. However, New Caledonia has not yet made any decision, since an independence referendum may be held in 2014 or later, and opinions differ about whether the euro should be used or not in the future. The French government has required that all three entities will have to decide in favour to join. After such a decision, the government would make the application on their behalf at the European Council, and the switch to euro could be made after a couple of years.[76]

Summary of adoption progress

The new member states, who have joined the union in 2004 and later, shall adopt the euro as soon as they meet the criteria. For them, the single currency was "part of the package" of European Union membership. Unlike for the UK and Denmark, "opting out" is not permitted.

The remaining states are expected to enter the third stage of the EMU and adopt the euro at different paces: 2012 for Bulgaria and Latvia; early 2013 for Lithuania; 2014 or 2015 for Poland; 2015 for Romania. The Czech Republic was set to join on 1 January 2010, but can no longer do so due to economic conditions. A new date has not been set; it might not be before 2015. Hungary has also abandoned its original target date of 2010, without setting any new date.

On 16 May 2006, the European Commission recommended Slovenia to become a new member of the eurozone. This occurred on 1 January 2007. In May 2007, the European Commission recommended the same for Cyprus and Malta, and their accession to the eurozone took place on 1 January 2008. On 7 May 2008, the European Commission recommended the same for Slovakia, which joined the eurozone on 1 January 2009.

Showing the ability to move towards full economic and monetary union is one requisite of "good membership". The ECB and European Commission produce reports every two years analysing the economic and other conditions of non-eurozone EU members, reporting on their suitability for joining the eurozone. The first to include the 10 new members was published in October 2004.[77]

| State |

Target |

ERM entry |

Co- ordinating institution |

Changeover plan |

Intro- duction |

Dual circulation period |

Exchange till |

Dual price display |

National mint |

Coin design |

Currency needed |

Law |

Commu- nication strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 January 2015 | Unknown | Not yet approved | 15 days | Central bank: indefinitely | Yes | Approved 1 design |

|||||||

| Not set | Unknown | Big-Bang | Yes | Public survey under consideration |

|||||||||

| Not before 2014 | 28 June 2004 | Commission for the Coordination of the Adoption of the euro in Lithuania, created on 30 May 2005 | First version approved by the government on 27 September 2005 | Big-Bang [citation needed] |

60 calendar days before and after €-day | Yes | Approved 3 designs |

118.3 million banknotes, 290 million coins | Draft law on the adoption of the euro is prepared | Endorsed by the government on 27 September 2005 | |||

| 1 January 2015[61] | Expected in 2013–2014[62] | Inter-institutional working group MoF-NBP | 11 months[78] | Yes | Not yet decided |

||||||||

| Not before 2014 | 2 May 2005 | The Steering Committee for the preparation and coordination of the euro changeover was established on 18 July 2005 | Approved on 6 July 2005 | Big-Bang with possible phase out features | 2 weeks | October 2007 – June 2008 | No | Approved 3 designs |

87 million banknotes and 300 million coins | ||||

| Not set | Not before 2015 | Approved on 11 April 2007[citation needed] | Big-Bang | 5 months before adoption 12 months after adoption |

Yes | Competition under consideration |

230 million banknotes and 950 million coins | ||||||

| Not set | Unknown | Preparatory work is ongoing in the Ministry of Finance and Magyar Nemzeti Bank (Central Bank of Hungary) | Big-Bang with possible phase out features [citation needed] |

1 month | Yes | Not yet decided |

|||||||

| Possibility of a future referendum | 1 January 1999 | Yes | |||||||||||

| Not under consideration | Not under consideration | ||||||||||||

| Not under consideration | Not under consideration |

See also

Notes and references

Notes

- ^ The Bulgarian National Bank pursues its primary objective of price stability through an exchange rate anchor in the context of a Currency Board Arrangement (CBA), obliging them to exchange monetary liabilities and euro at the official exchange rate 1.95583 BGN/EUR without any limit. The CBA was introduced on 1 July 1997 as a 1:1 peg against German mark, and the peg subsequently changed to euro on 1 January 1999.[20]

- ^ Sweden, while obliged to adopt the euro under its Treaty of Accession, has chosen to deliberately fail to meet the convergence criteria for euro adoption by not joining ERM II without prior approval by a referendum.

References

- ^ Kubosova, Lucia (5 May 2008)). "Slovakia confirmed as ready for Euro". euobserver.com. Retrieved 25 January 2009.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Ministers offer Estonia entry to eurozone January 1". France24.com. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- ^ a b Lithuanian PM keen on fast-track euro idea, The Baltic Course, 8 April 2009

- ^ "HICP (2005=100): Monthly data (12-month average rate of annual change)". Eurostat. 16 August 2012. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ "The corrective arm/ Excessive Deficit Procedure". European Commission. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ "Long-term interest rate statistics for EU Member States (monthly data for the average of the past year)". Eurostat. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ "Government deficit/surplus, debt and associated data". Eurostat. 22 April 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ^ "General government debt". Eurostat. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ "ERM II – the EU's Exchange Rate Mechanism". European Commission. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ "Euro/ECU exchange rates - annual data". Eurostat. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ "Former euro area national currencies vs. euro/ECU - annual data". Eurostat. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d e "Convergence Report June 2024" (PDF). European Central Bank. 26 June 2024. Retrieved 26 June 2024.

- ^ "Convergence Report 2024" (PDF). European Commission. 26 June 2024. Retrieved 26 June 2024.

- ^ "Luxembourg Report prepared in accordance with Article 126(3) of the Treaty" (PDF). European Commission. 12 May 2010. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ "EMI Annual Report 1994" (PDF). European Monetary Institute (EMI). April 1995. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ a b "Progress towards convergence - November 1995 (report prepared in accordance with article 7 of the EMI statute)" (PDF). European Monetary Institute (EMI). November 1995. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ AFP

- ^ a b "Foreign exchange operations". European Central Bank. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- ^ "Convergence Report June 2024" (PDF). European Central Bank. 26 June 2024. Retrieved 27 June 2024.

- ^ "EUROPEAN ECONOMY 4/2014: Convergence Report 2014" (PDF). European Commission. 4 June 2014.

- ^ "The National Assembly adopted at first reading a bill for the introduction of the euro in the Republic of Bulgaria". Parliament.bg. National Assembly of Bulgaria. 26 July 2024. Retrieved 7 August 2024.

- ^ a b "България покрива всички критерии, остава само инфлацията за членство в еврозоната, според редовните конвергентни доклади за 2024 г. на Европейската комисия и на Европейската централна банка" [Bulgaria meets all criteria, only inflation remains for eurozone membership, according to the regular convergence reports for 2024 of the European Commission and the European Central Bank]. Evroto.bg (in Bulgarian). Ministry of Finance (Bulgaria). 26 June 2024.

- ^ "Czech Government to Evaluate Merits of Joining 'Euro Waiting Room'". Reuters. 7 February 2024. Retrieved 7 February 2024.

- ^ "Denmark's Zeitenwende". European Council on Foreign Relations. 7 June 2022. Retrieved 25 February 2024.

- ^ "Regeringsgrundlag December 2022: Ansvar for Danmark (Government manifest December 2022: Responsibility for Denmark)" (PDF) (in Danish). Danish Ministry of Finance. 14 December 2022.

- ^ "Orbán: Hungary will not adopt the euro for many decades to come". Hungarian Free Press. 3 June 2015.

- ^ "Poland is still not ready to adopt the euro, its finance minister says". Ekathimerini.com. 30 April 2024.

- ^ Smarandache, Maria (20 March 2023). "Romania wants to push euro adoption by 2026". Euractiv.com. Retrieved 27 February 2024.

- ^ Smarandache, Maria (24 March 2023). "Iohannis: No 'realistic' deadline for Romania to join eurozone". Euractiv.com. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ Balázs Márton (20 March 2023). "Románia előrébb hozná az euró bevezetését" [Romania would advance the introduction of the euro]. Telex.hu (in Hungarian). Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ "DN Debatt Repliker. 'Folkligt stöd saknas för att byta ut kronan mot euron'" [DN Debate Replicas. "There is no popular support for exchanging the krona for the euro"]. Dagens Nyheter (in Swedish). 3 January 2022. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ^ Stratton, Allegra (22 November 2007). "Danes to hold referendum on relationship with EU". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 22 November 2007.

- ^ "Løgtingsmál nr. 11/2009: Uppskot til samtyktar um at taka upp samráðingar um treytir fyri evru sum føroyskt gjaldoyra (Faroese)" (PDF). Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- ^ "Rich Faroe Islands may adopt euro". Fishupdate.com. 12 August 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- ^ "Euro wanted as currency in Faroe Islands". Icenews.is. 8 August 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- ^ "Don't look for the Euro until after 2012". New Europe. 18 August 2007. Archived from the original on 23 December 2007. Retrieved 27 December 2007.

- ^ "Bank targets 2013 as Latvia's 'E-day'". baltictimes.com. 26 October 2007. Retrieved 28 October 2007.

- ^ Pop, Valentina (15 September 2011). "Latvia aiming to join eurozone in 2014". EU Observer. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ^ Adoption of the euro in Lithuania, Bank of Lithuania. Retrieved 11 January 2007.

- ^ "Lithuanian PM says aiming for euro by 2010–2011". Forbes. 12 April 2007. Retrieved 3 January 20083.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Pavilenene, Danuta (8 December 2008). "SEB: no euro for Lithuania before 2013". The Baltic Course. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- ^ FEATURE – Crisis, not Greece, makes euro hopefuls cautious, Reuters, 18 January 2010

- ^ "Bulgaria's budget of reform". The Sofia Echo. 30 November 2007. Retrieved 3 January 2008.

- ^ "Bulgaria could join euro zone ahead of other eu countries".

- ^ "said to pressure Bulgaria into discontinuing currency board".

- ^ "The Sofia Echo". Retrieved 17 May 2008.

- ^ byDnevnik.bg (17 September 2009). "Bulgaria to seek eurozone entry within GERB's term – Finance Minister". Sofia Echo. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- ^ M3 Web – http://m3web.bg (22 December 2009). "Bulgaria: Bulgaria to Apply for ERM 2 in March". Sofia. Novinite. Retrieved 31 July 2010.

{{cite news}}: External link in|author= - ^ "Bulgaria delays eurozone application as deficit soars". Eubusiness.com. 9 April 2010. Retrieved 31 July 2010.

- ^ "Bulgaria's Eurozone accession drifts away". Retrieved 25 November 2008.

- ^ "Euros in the wallets of the Slovaks, but who will be next?" (Press release). Sparkasse.at. 5 August 2008. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- ^ Czech Republic – Factors To Watch, Reuters, 20 January 2010

- ^ For Czechs, euro adoption still a long way off, Czech Radio, 9 June 2008

- ^ a b "Czechs, Poles cooler to euro as they watch debt crisis". Reuters. 16 June 2010. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- ^ "Czech crown to stay long with no euro opt-out needed: PM". Reuters. 5 December 2010.

- ^ Laca, Peter. "Czech Republic Still Able to Opt Out of Adopting Euro, Prime Minister Says". Bloomberg. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- ^ "FACTBOX-Where Eastern Europeans stand on euro adoption". Forbes. 22 January 2009. Retrieved 31 July 2010.

- ^ "Poland may adopt euro before 2014-Deputy FinMin". Forbes. 10 July 2009. Retrieved 31 July 2010.

- ^ Bloomberg Businessweek. 2 December 2011. Official: Poland to be ready for euro in 4 years

- ^ "60 proc. Polaków nie chce euro" (in Polish). Wirtualna Polska. 14 February 2012. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ^ a b "Raport privind situația macroeconomică" (PDF). Government of Romania. Retrieved 31 December 2009.

- ^ a b http://business-review.ro/news/update-new-euro-adoption-target-to-be-set-by-the-end-of-the-month-pm/11455/

- ^ "European Union Agreement Details". Council of the European Union. Retrieved 26 December 2008.

- ^ "Folkomröstning 14 september 2003 om införande av euron" (in Swedish). Swedish Election Authority. Retrieved 2 February 2008.

- ^ "Glöm euron, Reinfeldt" (in Swedish). Aftonbladet. 2 December 2007. Retrieved 3 February 2008.

- ^ At-a-glance: Cameron coalition's policy plans, 13 May 2010, retrieved 13 September 2010

- ^ "Make Way for Britain's New Coin Designs". Retrieved 17 May 2008.

- ^ "No 10 denies shift in euro policy". BBC. 1 December 2008. Retrieved 1 December 2008.

- ^ "UPDATE 1-EU's Almunia: high chance UK to join euro in future" in.reuters.com, 2 February 2009, Link retrieved 2 February 2009

- ^ "Monetary Agreement between the European Union and the Principality of Andorra".

- ^ Croatia ready to join EU in 2013 – official reuters.com, 2011-06-10

- ^ Iceland cannot adopt the Euro with joining EU, says Stark (sic)

- ^ http://www.sedlabanki.is/?PageID=202

- ^ http://www.sedlabanki.is/?PageID=224

- ^ http://www.ministryoffinance.is/government-finance/debt-statistics/

- ^ "Nouvelle-Calédonie : Entre Émancipation, Passage A L'Euro Et Recherche De Ressources Nouvelles" (PDF). Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- ^ "Convergence Report". European Central Bank. 2006. Retrieved 12 September 2006.

- ^ "Guvernanţi: România poate adopta euro în 2015", in Evenimentul Zilei, 29 April 2011