Ernest J. King

Ernest J. King | |

|---|---|

Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King, USN | |

| Birth name | Ernest Joseph King |

| Nickname(s) | "Ernie" "Rey" |

| Born | 23 November 1878 Lorain, Ohio |

| Died | 25 June 1956 (aged 77) Kittery, Maine |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1901–1956[1] |

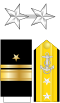

| Rank | |

| Commands | United States Fleet |

| Battles / wars | Spanish–American War Mexican Revolution World War II |

| Awards | Navy Cross Navy Distinguished Service Medal (3) Sampson Medal |

| Other work | Naval Historical Foundation, President |

Ernest Joseph King (23 November 1878 – 25 June 1956) was Commander in Chief, United States Fleet (COMINCH) and Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) during World War II. As COMINCH-CNO, he directed the United States Navy's operations, planning, and administration and was a member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. He was the U.S. Navy's second most senior officer after Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy, and the second admiral to be promoted to five star rank.

Historian Michael Gannon blamed King for the heavy American losses during the Second Happy Time. Others however blamed the belated institution of a convoy system, partly due to a severe shortage of suitable escort vessels, without which convoys were seen as more vulnerable than lone ships.[2]

Early life

King was born in Lorain, Ohio, on 23 November 1878, the son of James Clydesdale King and Elizabeth Keam King.[3] He attended the United States Naval Academy from 1897 until 1901, graduating fourth in his class. During his senior year at the Academy, he attained the rank of Midshipman Lieutenant Commander, the highest midshipman ranking at that time.[4]

Surface ships

While still at the Academy, he served on the USS San Francisco during the Spanish–American War. After graduation, he served as a junior officer on the survey ship USS Eagle, the battleships USS Illinois, USS Alabama and USS New Hampshire, and the cruiser USS Cincinnati.[5]

King returned to shore duty at Annapolis in 1912. He received his first command, the destroyer USS Terry in 1914, participating in the United States occupation of Veracruz.[6] He then moved on to a more modern ship, USS Cassin.

During World War I he served on the staff of Vice Admiral Henry T. Mayo, the Commander in Chief, Atlantic Fleet. As such, he was a frequent visitor to the Royal Navy and occasionally saw action as an observer on board British ships. It appears that his Anglophobia developed during this period,[7] although the reasons are unclear. He was awarded the Navy Cross "for distinguished service in the line of his profession as assistant chief of staff of the Atlantic Fleet."[8] It was after World War I that King affected his signature manner of wearing his uniform, with a breast-pocket handkerchief under his ribbons (see image, top right). Officers serving alongside the Royal Navy did this in emulation of Admiral David Beatty, RN. King was the last to continue.[9]

After the war, King, now a captain, became head of the Naval Postgraduate School. Along with Captains Dudley Wright Knox and William S. Pye, King prepared a report on naval training that recommended changes to naval training and career paths. Most of the report's recommendations were accepted and became policy.[10]

Submarines

Before World War I he served in the surface fleet. From 1923 to 1925, he held several posts associated with submarines. As a junior captain, the best sea command he was able to secure in 1921 was the store ship USS Bridge. The relatively new submarine force offered the prospect of advancement.[11]

King attended a short training course at the Naval Submarine Base New London before taking command of a submarine division, flying his commodore's pennant from USS S-20. He never earned his Submarine Warfare insignia, although he did propose and design the now-familiar dolphin insignia. In 1923, he took over command of the Submarine Base itself.[12] During this period, he directed the salvage of USS S-51, earning the first of his three Distinguished Service Medals.

Aviation

In 1926, Rear Admiral William A. Moffett, Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics (BuAer), asked King if he would consider a transfer to naval aviation. King accepted the offer and took command of the aircraft tender USS Wright with additional duties as senior aide on the staff of Commander, Air Squadrons, Atlantic Fleet.[13]

That year, the United States Congress passed a law (10 USC Sec. 5942) requiring commanders of all aircraft carriers, seaplane tenders, and aviation shore establishments be qualified naval aviators or naval aviation observers. King therefore reported to Naval Air Station Pensacola, Florida for aviator training in January 1927. He was the only captain in his class of twenty, which also included Commander Richmond K. Turner. King received his wings as Naval Aviator No. 3368 on 26 May 1927 and resumed command of Wright. For a time, he frequently flew solo, flying down to Annapolis for weekend visits to his family, but his solo flying was cut short by a naval regulation prohibiting solo flights for aviators aged 50 or over.[14] However, the history chair at the Naval Academy from 1971 to 1976 disputes this assertion, stating that after King soloed, he never flew alone again.[15] His biographer described his flying ability as "erratic" and quoted the commander of the squadron with which he flew as asking him if he "knew enough to be scared?"[16] Between 1926 and 1936 he flew an average of 150 hours annually.[17]

King commanded Wright until 1929, except for a brief interlude overseeing the salvage of USS S-4. He then became Assistant Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics under Moffett. The two fell out over certain elements of Bureau policy, and he was replaced by Commander John Henry Towers and transferred to command of Naval Station Norfolk.[18]

On 20 June 1930, King became captain of the carrier USS Lexington—then one of the largest aircraft carriers in the world—which he commanded for the next two years.[19] During his tenure aboard the Lexington, Captain King was the commanding officer of notable science fiction author Robert A. Heinlein, then Ensign Heinlein, prior to his medical retirement from the US Navy. During that time, Ensign Heinlein dated one of King's daughters.[20]

In 1932, King attended the Naval War College. In a war college thesis entitled "The Influence of National Policy on Strategy", King expounded on the theory that America's weakness was Representative democracy:

Historically ... it is traditional and habitual for us to be inadequately prepared. This is the combined result of a number factors, the character of which is only indicated: democracy, which tends to make everyone believe that he knows it all; the preponderance (inherent in democracy) of people whose real interest is in their own welfare as individuals; the glorification of our own victories in war and the corresponding ignorance of our defeats (and disgraces) and of their basic causes; the inability of the average individual (the man in the street) to understand the cause and effect not only in foreign but domestic affairs, as well as his lack of interest in such matters. Added to these elements is the manner in which our representative (republican) form of government has developed as to put a premium on mediocrity and to emphasise the defects of the electorate already mentioned.[21]

Following the death of Admiral Moffet in the crash of the airship USS Akron on 4 April 1933, King became Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics, and was promoted to rear admiral on 26 April 1933.[22] As bureau chief, King worked closely with the chief of the Bureau of Navigation, Rear Admiral William D. Leahy, to increase the number of naval aviators.[23]

At the conclusion of his term as bureau chief in 1936, King became Commander, Aircraft, Base Force, at Naval Air Station North Island, California.[24] He was promoted to Vice Admiral on 29 January 1938 on becoming Commander, Aircraft, Battle Force – at the time one of only three vice admiral billets in the US Navy.[25] Among his accomplishments was to corroborate Admiral Harry E. Yarnell's 1932 war game findings in 1938 by staging his own successful simulated naval air raid on Pearl Harbor, showing that the base was dangerously vulnerable to aerial attack, although he was taken no more seriously than his contemporary until Dec. 7, 1941 when the Imperial Japanese Navy attacked the base by air for real.[26]

King hoped to be appointed as either CNO or COMINCH, but on 15 June 1939, he was posted to the General Board, an elephants' graveyard where senior officers spent the time remaining before retirement. A series of extraordinary events would alter this outcome.[27]

World War II

King's career was resurrected by his friend, the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO), Admiral Harold "Betty" Stark, who realized King's talent for command was being wasted on the General Board. Stark appointed King as Commander-in-Chief, Atlantic Fleet in the fall of 1940, and he was promoted to admiral in February 1941. On 30 December 1941 he became Commander-in-Chief, United States Fleet (COMINCH). On 18 March 1942, he was appointed Chief of Naval Operations, relieving Stark. He is the only person to hold this combined command. After turning 64 on 23 November 1942, he wrote a message to President Roosevelt to say he had reached mandatory retirement age. Roosevelt replied with a note reading "So what, old top?".[28] On 17 December 1944 King was promoted to the newly created rank of fleet admiral. He left active duty on 15 December 1945 but was recalled as an advisor to the Secretary of the Navy in 1950.

Retirement and death

After retiring, King lived in Washington, D.C.. He was active in his early post-retirement (serving as president of the Naval Historical Foundation from 1946 to 1949), but suffered a debilitating stroke in 1947, and subsequent ill-health ultimately forced him to stay in naval hospitals at Bethesda, Maryland, and at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in Kittery, Maine. He died of a heart attack in Kittery on 25 June 1956.[29] After lying in state at the National Cathedral in Washington, King was buried in the United States Naval Academy Cemetery at Annapolis, Maryland. His wife who survived him, was buried beside him in 1969.

Analysis

King was highly intelligent and extremely capable, but controversial. Some consider him to have been one of the greatest admirals of the 20th century;[30] others, however, point out that he never commanded ships or fleets at sea in war time, and that his Anglophobia led him to make decisions which cost many Allied lives.[31] Others see as indicative of strong leadership his willingness and ability to counter both British and U.S. Army influence on American World War II strategy, and praise his sometimes outspoken recognition of the strategic importance of the Pacific War.[30] His instrumental role in the decisive Guadalcanal Campaign has earned him admirers in the United States and Australia, and some also consider him an organizational genius.[32] He was demanding and authoritarian, and could be abrasive and abusive to subordinates. King was widely respected for his ability, but not liked by many of the officers he commanded. John Ray Stakes described him as:

…perhaps the most disliked Allied leader of World War II. Only British Field Marshal Montgomery may have had more enemies... King also loved parties and often drank to excess. Apparently, he reserved his charm for the wives of fellow naval officers. On the job, he "seemed always to be angry or annoyed."[33]

There was a tongue-in-cheek remark about King, made by one of his daughters, repeated by Naval personnel at the time, that "he is the most even-tempered person in the United States Navy. He is always in a rage." Roosevelt once described King as a man who "shaves every morning with a blow torch."[34]

It is commonly reported when King was called to be COMINCH, he remarked, "When they get in trouble they send for the sons-of-bitches." However, when he was later asked if he had said this, King replied he had not, but would have if he had thought of it.[35] On the other hand, King's view of press relations for the US Navy in World War II is well documented. When asked to state a public relations policy for the Navy, King replied "Don't tell them anything. When it's over, tell them who won." [36]

Response to Operation Drumbeat

At the start of US involvement in World War II, blackouts on the U.S. eastern seaboard were not in effect, and commercial ships traveling the coastal waterways were not travelling under convoy. King's critics attribute the delay in implementing these measures to his Anglophobia, as the convoys and seaboard blackouts were British proposals, and King was supposedly loath to have his much-beloved U.S. Navy adopt any ideas from the Royal Navy. He also refused, until March 1942, the loan of British convoy escorts when the Americans had only a handful of suitable vessels. He was, however, aggressive in driving his destroyer captains to attack U-boats in defense of convoys and in planning counter-measures against German surface raiders, even before the formal declaration of war in December 1941.[37]

Instead of convoys, King had the U.S. Navy and U.S. Coast Guard perform regular anti-submarine patrols, but these patrols followed a regular schedule. U-boat commanders learned the schedule, and coordinated their attacks to these schedules. Leaving the lights on in coastal towns back-lit merchant ships for the U-Boats. As a result, there was a period of disastrous shipping losses—two million tons lost in January and February 1942 alone, and urgent pressure applied from both sides of the Atlantic. However, King resisted the use of convoys because he was convinced the Navy lacked sufficient escort vessels to make them effective. The formation of convoys with inadequate escort would also result in increased port-to-port time, giving the enemy concentrated groups of targets rather than single ships proceeding independently. Furthermore, blackouts were a politically sensitive issue—coastal cities resisted, citing the loss of tourism revenue.[citation needed]

It was not until May 1942 that King marshalled resources—small cutters and private vessels that he had previously scorned—to establish a day-and-night interlocking convoy system running from Newport, Rhode Island, to Key West, Florida.[38]

By August 1942, the submarine threat to shipping in U.S. coastal waters had been contained. The U-boats' "second happy time" ended, with the loss of seven U-boats and a dramatic reduction in shipping losses. The same effect occurred when convoys were extended to the Caribbean. Despite the ultimate defeat of the U-boat, some of King's initial decisions in this theatre could be viewed as flawed.[39]

In King's defense, noted naval historian Professor Robert W. Love has stated that:

Operation Drumbeat (or Paukenschlag) off the Atlantic Coast in early 1942 succeeded largely because the U.S. Navy was already committed to other tasks: transatlantic escort-of-convoy operations, defending troop transports, and maintaining powerful, forward-deployed Atlantic Fleet striking forces to prevent a breakout of heavy German surface forces. Navy leaders, especially Admiral King, were unwilling to risk troop shipping to provide escorts for coastal merchant shipping. Unscheduled, emergency deployments of Army units also created disruptions to navy plans, as did other occasional unexpected tasks. Contrary to the traditional historiography, neither Admiral King's unproven yet widely alleged Anglophobia, an equally undocumented navy reluctance to accept British advice, nor a preference for another strategy caused the delay in the inauguration of coastal escort-of-convoy operations. The delay was due to a shortage of escorts, and that resulted from understandably conflicting priorities, a state of affairs that dictated all Allied strategy until 1944.[40][page needed]

Context for the US Navy's and Admiral King's Response to Operation Drumbeat

AUTHORITY: Admiral King assumed the appointment as COMINCH, US Fleet on December 20, 1941 from Admiral Kimmel. While the command provided operational control of the three US Navy Fleets and coastal vessels, Admiral Stark was the Chief of Naval Operations which included responsibilities under Article 392 and Article 433, US Navy Regulations (“The Chief of Naval Operations shall, under the direction of the Secretary of the Navy, be charged with the operations of the fleet and with the preparation and readiness of plans for its use in war, Act of 3 Mar. 1915").[[41]] Admiral King was not appointed to the dual role of Chief of Naval Operations until the issuance of the General Order No. 170, dated March 23, 1942.

AVAILABILITY of VESSELS (based on a variety of sources[[42]]): An analysis of the disposition of US Naval vessels in December, 1941 highlights a total of about 300 “patrol capable vessels” (DD, PG, PC, Coast Guard Cutters, PY and PYc types) including those in overhauls, major repairs and fitting-out. The inventory includes 171 destroyers of which over 40% were WWI era types, about 52 “Patrol Types” (PG, PY, PYc) including Spanish American War trophies and a collection of about 76 Coast Guard Cutters (not including the 10 of the 21 larger 250+’ cutters given to the British).

The US Atlantic Fleet contained 100% of the newer Sims, Benson and Gleaves destroyer classes. Of the 91 destroyers deployed in US Atlantic Fleet (leaving only 66 in the US Pacific and 13 in the US Asiatic Fleets), 52 US Atlantic Fleet destroyers were deployed either on Atlantic Convoy duty (including a squadron escorting British Troop transports around Cape Town), in Iceland or Newfoundland; only 24 were either in US Atlantic ports (including those be fitted-out, repairs) or serving as capital ship escorts; four were stationed in Bermuda; and the remaining 8 were stationed at the Canal Zone working convoys or in port. The US Atlantic Fleet accounted for 37 Patrol type (leaving a handful for the Pacific and Asiatic Fleets) vessels with 7 assigned to the Caribbean and the 54 of the Coast Guard Cutters with 26 assigned to Greenland/Newfoundland/Iceland Patrols.[[43]]

If one looks at the building programs for FY39 and FY40, the US Navy had 194 destroyers (some ordered in June and July 1940), 140 Patrol Craft (PC's 173', 165', 110'), 78 Sub Chasers (SC’s) and 129 YMS’s (which could be utilized for anti-sub role if necessary).[[44]] Of the Destroyers laid down in 1940-1 that were not commissioned on December 7, twenty-eight were commissioned between January and June of 1942 with 16 assigned to the US Atlantic Fleet or the European Theater of Operations (ETO) and 12 assigned to the US Pacific Fleet (and of the 12, 1/3 conducted anti-submarine/convoy duty in the Atlantic/Caribbean prior to reporting to the Pacific Fleet) and, of the remaining fifty-two of the classes of 1940-1, 35 were commissioned and assigned to the US Atlantic Fleet and/or the ETO.

As for coastal class escorts, the US Navy commissioned 126 vessels in the period January to June 1942 with 83 being assigned to the US Atlantic Fleet. The bulk of the vessels were of the new 173’ PC and 110’ SC (some 110' PC reassigned as SC types) classes. During the same period, the Coast Guard commissioned 11 vessels with 10 being assigned to the Greenland/Newfoundland Patrols. For the period July–December 1943, the Navy commissioned an additional 52 Patrol Craft and, while the data on the 110’ SC’s is a little lacking, the pattern seems to remain with the bulk of the vessels being assigned to the US Atlantic Fleet while the US Coast Guard commissioned 21 vessels with 19 going to the Greenland/Newfoundland Patrols. In addition, a number of other vessels types were being launched configured for escorts like the seven Cactus Class Lighthouse Tenders in 1942 (as well as the follow-on Cactus and Mesquite Classes); the Admirable class minesweepers; and the YMS class minesweepers. The US Coast Guard drafted almost every vessel type including sea going tugs, weather ships, icebreakers, and converted freighters into the Greenland Patrol.

Prior and during WWII, the US Navy instituted the procurement and modification of civilian/commercial vessels as it has in times of conflict since the Revolution. The effort began in earnest with the efforts to enforce the Neutrality Patrols and continued past December 1941. In fact of the “Patrol” types available prior to December 1941, the majority of them were acquired, converted craft (PG, PY, PYc). The Navy extended the acquisitions especially of fishing vessels to fill mine-sweeping and harbor patrol duties (AM, AMc types). The US Coast Guard (under the command of the US Navy) continued to acquire commercial and fishing vessel types as Patrol Cutters (WPG, WYP, WYPc, WAK) into early stages of the war with 95% being utilized to the east coast but the majority assigned to the Greenland Patrol.

As to Escort Carriers, two “Escort Carriers” (AVG/CVE Types) following the general design of the USS Long Island (acquired March 1941) were built prior to December 1941 with one being siphoned-off by the UK. During the first half of 1942, four CVE’s were commissioned with two going to the UK with the other two being assigned to the US Navy with one each to the Pacific and Atlantic. In the last half of 1942, fifteen CVE’s were commissioned with six going to the UK, and all but one of the US Navy units initially assigned to the Atlantic Fleet. The US manned CVE’s carried a more robust air wing the previous UK-built/manned vessels and, obviously, the UK units were not assigned to the daunting tasks facing the US Navy.

AVAILABILITY of Naval Patrol Aircraft (based on a variety of sources[45]]): As to Naval aviation, a review of the “Dictionary American Naval Aviation Squadrons” and the declassified “Location of U.S. Naval Aircraft” show on February 2, 1942 the US Navy had 102 “primary” patrol aircraft (PBY-5, PV-1, PB4Y-1 (B-24), and PBM-3) deployed in nine squadrons in the US Atlantic Fleet (Gulf, Caribbean and the Atlantic) including about 33% of the squadrons deployed to Newfoundland or Iceland (and net of VP-72 and VP-71). The Navy had 110 aircraft (post the losses to the Japanese and with the US Asiatic Fleet and with the inclusion of the two transferred squadrons from the Atlantic) in fourteen squadrons in the greater Pacific. Of course, one can point to the transfer after Pearl Harbor of VP-72 and VP-71 from the Atlantic as bias, but one must consider the losses inflicted by the Japanese. In addition, 51 shorter range in-shore patrol aircraft were assigned to the US Atlantic Fleet while 42 were posted in the Pacific.

By June 25, 1942, the US Navy had 168 “primary” patrol aircraft in the “Battle for the Atlantic” zones in 15 squadrons while 176 aircraft (including the remainder of the US Asiatic Squadrons) in the greater Pacific. The US Navy assigned 148 in-shore patrol aircraft in the Atlantic Fleet while 86 were assigned in the Greater Pacific. By December 8, 1942, the US Navy increased the “primary” patrol aircraft to 174 in the Atlantic with a net of 164 in the Pacific (net of headquarters and training commands and squadrons being trained). Actually, the US Atlantic Fleet training commands which conducted anti-submarine and convoy escort missions had more aircraft than the Pacific units.

INTER-SERVICE CHALLENGES: As put forward in the Army Antisubmarine Command History, there were “conflicts” between the Navy and the Army addressing defense from seaborne treats along the coasts. Under the Joint Action of the Army and Navy (FTP-155, 1935), the Navy had responsibility for seaborne coastal patrols and there was no debate over the Navy operating seaplanes and carrier-class aircraft. General Arnold was opposed to the Navy operating land-based bombers and to Admiral King’s request of 200 B-24’s and 400 B-25’s for long range patrol. On the Army Air Forces side, little was done to provide the necessary air assets when the US Navy requested the US Army Air Force (AAF) assign I Bomber Command to support the Atlantic Fleet. The Command was thrown into the gap stripped of most of its long-range aircraft. If fact by January 1943, the two AAF commands tasked to support the US Navy’s effort could put together only 139 operational aircraft (given strains of the build-up in the ETO).[[46]]

STAFFING: The US Navy had about 160,000 personnel in 1940 building to 640,570 plus 56,716 USCG in 1942 to over 3.3 million by the end of the war. Thus in 1941 into early 1942, the meager availability of trained officers and NCOs had to be metered out to crews for new capital ships, supply operations, medical operations, repair and maintenance operations, air wings, etc. Patrol craft and Destroyers assignments were some of the most challenging non-flight assignments given the reliance on junior officers.[[47]]

BLACK-OUTS/DIM-OUTS: There is some support for Admiral King’s reliance on FDR to order blackouts/dim-outs along the coasts. The order could have very quickly come from FDR (as an Executive Order); FDR could have expedited a request Congress to enact emergency legislation; or quickly contacted the Governors of the relevant states to address the situation.

THREATS IN THE PACIFIC: In the first six months to a year of 1942, the Japanese could have utilized their 65[[48]] (63 ocean-going submarines) submarines to conduct anti-shipping campaign either to cut-off Hawaii or Australia/New Zealand (remember, Japanese subs were present at Pearl Harbor and sited in the Philippines) especially from their newly won bases.

There is no statistical evidence Admiral King stripped the Atlantic Fleet to fill the gaps in the Pacific nor is the evidence the US Navy had neglected the preparation for anti-submarine warfare or ignored the learning from WWI, the Neutrality Patrols or the early Battle of the Atlantic. The attack on Pearl Harbor caught the US Navy in the early stages of operationalization. One can praise the US Navy for its ability to implement convoys so quickly with a bevy of essentially “green” crews, new vessels and new aircraft coming “on line.” If the war had started six months later the Germans would have been facing a very different US Navy.

A lesser leader could have pointed to the intense commitment to the Atlantic convoys system to the UK and Russia; augment the British Home Fleet; and/or support Australia and New Zealand (as the British Navy had) and would have demanded relocation of experienced crews and vessels back to US waters (as well as fought to eliminate any further lead-lease deployment of naval escort-grade vessels). Admiral King stayed the course and the US Navy reasserted itself both in the “Battle of the Atlantic” and, with no help from the British, in a string of great victories in the Pacific. The bottom line is if FDR thought Admiral King was incompetent Admiral King would have been fired.

Other decisions

Other decisions widely regarded as questionable were his resistance to the employment of long-range USAAF B-24 Liberator on Atlantic maritime patrols (thus allowing the U-boats a safe area in the middle of the Atlantic — the "Atlantic Gap")(see "INTER-SERVICE CHALLENGES" as well as the fact of the 13 PB4Y Naval Aviation Squadrons commissioned in 1943, 8 were initially deployed to the Atlantic Fleet), the denial of adequate numbers of landing craft to the Allied invasion of Europe (a very broad assertion since the US war production was in civilian hands and the Joint Chiefs recommended to the President the deployment priorities as well as the fact of the added drain on landing craft caused by Battle of Anzio), and the reluctance to permit the Royal Navy's Pacific Fleet any role in the Pacific (again, a broad assertion which has been treated in depth in a variety of recent histories of the War in the Pacific pointing to the complexities of integrating a British naval force which did not have an adequate supply infrastructure nor proven ability to operate with the US Navy's Fast Carrier groups). In all of these instances, circumstances forced a re-evaluation or he was overruled. It has also been pointed out that King did not, in his post-war report to the Secretary of the Navy, accurately describe the slowness of the American response to the off-shore U-boat threat in early 1942.[49]

It should be noted, however, employment of long-range maritime patrol aircraft in the Atlantic was complicated by inter-service squabbling over command and control (the aircraft belonged to the Army; the mission was the Navy's; Secretary of War Stimson and General Arnold initially refused to release the aircraft).[50] This was later mitigated later in 1942 and into 1943 by the assignment of Navy-owned and operated PB4Y-1 Liberators, and by late 1944, the PB4Y-2 Privateer aircraft. Although King had certainly used the allocation of ships to the European Theatre as leverage to get the necessary resources for his Pacific objectives, he provided (at General Marshall's request) an additional month's production of landing craft to support Operation Overlord. Moreover, the priority for landing craft construction was changed, a factor outside King's remit. The level of sea lift for Overlord turned out to be more than adequate.

The employment of British and Empire forces in the Pacific was a political matter. The measure was forced on Churchill by the British Chiefs of Staff, not only to re-establish British presence in the region, but to mitigate any impression in the U.S. that the British were doing nothing to help defeat Japan. King was adamant that naval operations against Japan remain 100% American, and angrily resisted the idea of a British naval presence in the Pacific at the Quadrant Conference in late 1944, citing (among other things) the difficulty of supplying additional naval forces in the theatre (for much the same reason, Hap Arnold resisted the offer of RAF units in the Pacific). In addition, King (along with Marshall) had continually resisted operations that would assist the British agenda in reclaiming or maintaining any part of her pre-war colonial holdings in the Pacific or the Eastern Mediterranean. Roosevelt, however, overruled him and, despite King's reservations, the British Pacific Fleet accounted itself well against Japan in the last months of the war.[51]

General Hastings Ismay, chief of staff to Winston Churchill, described King as:[52]

...tough as nails and carried himself as stiffly as a poker. He was blunt and stand-offish, almost to the point of rudeness. At the start, he was intolerant and suspicious of all things British, especially the Royal Navy; but he was almost equally intolerant and suspicious of the American Army. War against Japan was the problem to which he had devoted the study of a lifetime, and he resented the idea of American resources being used for any other purpose than to destroy the Japanese. He mistrusted Churchill's powers of advocacy, and was apprehensive that he would wheedle President Roosevelt into neglecting the war in the Pacific.

Contrary to British opinion, King was a strong believer in the Germany first strategy. However, his natural aggression did not permit him to leave resources idle in the Atlantic that could be utilized in the Pacific, especially when "it was doubtful when — if ever — the British would consent to a cross-Channel operation".[53] King once complained that the Pacific deserved 30% of Allied resources but was getting only 15%. When, at the Casablanca Conference, he was accused by Field-Marshal Sir Alan Brooke of favoring the Pacific war, the argument became heated. The combative General Joseph Stilwell wrote: "Brooke got nasty, and King got good and sore. King almost climbed over the table at Brooke. God, he was mad. I wished he had socked him."[54]

Following Japan's defeat at the Battle of Midway, King advocated (with Roosevelt's tacit consent) the invasion of Guadalcanal. When General Marshall resisted this line of action (as well as who would command the operation), King stated the Navy (and Marines) would then carry out the operation by themselves, and instructed Admiral Nimitz to proceed with preliminary planning. King eventually won the argument, and the invasion went ahead with the backing of the Joint Chiefs. It was ultimately successful, and was the first time the Japanese lost ground during the war. For his attention to the Pacific Theatre he is highly regarded by some Australian war historians.[55]

In spite of (or perhaps partly because of) the fact the two men did not get along,[56] the combined influence of King and General Douglas MacArthur increased the allocation of resources to the Pacific War.[57]

Another controversy involving King was his role in the court-martial of Captain Charles B. McVay III.[58]

Personal life

While at the Naval Academy, King met Martha Rankin ("Mattie") Egerton, a Baltimore socialite, whom he married in a ceremony at the Naval Academy Chapel on 10 October 1905.[59] They had six daughters, Claire, Elizabeth, Florence, Martha, Eleanor and Mildred; and then a son, Ernest Joseph King, Jr. (Commander, USN ret.).[60]

Dates of rank

- Midshipman – June 1901

| Ensign | Lieutenant (junior grade) | Lieutenant | Lieutenant Commander | Commander | Captain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O-1 | O-2 | O-3 | O-4 | O-5 | O-6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 7 June 1903 | Never Held | 7 June 1906 | 1 July 1913 | 1 July 1917 | 21 September 1918 |

| Rear Admiral (lower half) | Rear Admiral | Vice Admiral | Admiral | Fleet Admiral |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O-7 | O-8 | O-9 | O-10 | O-11 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Never Held | 26 April 1933 | 29 January 1938 | 1 February 1941 | 17 December 1944 |

King never held the rank of lieutenant (junior grade) although, for administrative reasons, his service record annotates his promotion to both lieutenant (junior grade) and lieutenant on the same day.

- All DOR referenced from Buell's "Master of Sea Power", pp. xii–xv.

Awards and decorations

| |||

Foreign awards

King was also the recipient of several foreign awards and decorations (shown in order of acceptance and if more than one award for a country, placed in order of precedence):

| Grand Cross of the National Order of the Légion d'honneur (France) 1945 | |

| Croix de guerre (France) 1944 (attachment(s) unknown) | |

| Commander of the Order of Vasco Nunez de Balboa (Panama) 1929 | |

| Officer of the Order of the Crown of Italy 1933 | |

| Knight of the Grand Cross of the Military Order of Italy 1948 | |

| Order of Merit, Grande Official (Brazil) 1943 | |

| Order of Naval Merit (Cuba) 1943 | |

| Estrella Abdon Calderon (Ecuador) 1943 | |

| Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath (United Kingdom) 1945 | |

| Order of the Sacred Tripod (China) 1945 | |

| Grand Cross of the Order of George I (Greece) 1946 | |

| Grand Officer of the Order of the Crown (1948) | |

| Croix de Guerre (Belgium) (1948) (attachment(s) unknown) | |

| Knight Grand Cross with Swords of the Order of Orange-Nassau (Netherlands) 1948 |

Namesakes

The guided missile destroyer USS King was named in his honor. A major high school in his hometown of Lorain, Ohio, also bore his name (Admiral King High School) until it was merged with the city's other high school in 2010. In 2011 Lorain dedicated a Tribute Space at Admiral King's birthplace, and new elementary school in Lorain will bear his name. Also named after him is the Department of Defense high school on Sasebo Naval Base, in Japan. The dining hall at the U.S. Naval Academy, King Hall, is named after him. The auditorium at the Naval Postgraduate School, King Hall, is also named after him. In 1956, schools located on the U.S. Naval Bases and Air Stations were given names of U.S. heroes of the past. The Sasebo Dependents School was named after the famed World War II Hero, Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King. Thus, the official name of Ernest J. King School, Navy 3912, FPO San Francisco, California, became effective School Year 1956/57. Recognizing King's great personal and professional interest in maritime history, the Secretary of the Navy named in his honor an academic chair at the Naval War College to be held with the title of the Ernest J. King Professor of Maritime History. King Dr at Arlington National Cemetery is named in honor of Fleet Admiral King

References

- ^ U.S. officers holding five-star rank never retire; they draw full active duty pay for life.Spencer C. Tucker (2011). The Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. pp. 1685. ISBN 978-1-85109-961-0.

- ^ Timothy J. Ryan and Jan M. Copes To Die Gallantly – The Battle of the Atlantic, 1994 Westview Press, Chapter 7.

- ^ Buell, Master of Sea Power, p. 3.

- ^ Morison, The Battle of the Atlantic, p. 51.

- ^ Buell, Master of Sea Power, 1980, pp. 10–12, 15–41.

- ^ Martin Folly, Historical Dictionary of US Diplomacy

- ^ Gannon, Operation Drumbeat, p. 168.

- ^ "Full Text Citations For Award of The Navy Cross to Members of the US Navy World War I".

- ^ Young, Frank Pierce. "Pearl Harbor History: Building The Way To A Date Of Infamy". Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ^ Buell, Master of Sea Power, 1980, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Buell, Master of Sea Power, 1980, p. 58.

- ^ Buell, Master of Sea Power, 1980, pp. 62–64.

- ^ King and Whitehill, A Naval Record, p. 187.

- ^ King and Whitehill, A Naval Record, pp. 190–193.

- ^ Huston, John W. (2002). Maj. Gen. John W. Huston, USAF (ed.). American Airpower Comes of Age: General Henry H. "Hap" Arnold's World War II Diaries. Air University Press. p. 359. ISBN 1-58566-093-0.

- ^ Buell, Master of Sea Power, p. 76.

- ^ King and Whitehill, A Naval Record, p. 228.

- ^ King and Whitehill, A Naval Record, p. 211.

- ^ King and Whitehill, A Naval Record, p. 214.

- ^ William H. Patterson, Robert A. Heinlein: A Learning Curve'

- ^ King and Whitehill, A Naval Record, pp. 226–227.

- ^ King and Whitehill, A Naval Record, pp. 240–242.

- ^ King and Whitehill, A Naval Record, p. 249.

- ^ King and Whitehill, A Naval Record, p. 266.

- ^ King and Whitehill, A Naval Record, p. 279.

- ^ Rebekah. "The Day that Will Live in Infamy…but it didn't have to". The USS Flier Project. Retrieved 7 August 2012.

- ^ King and Whitehill, A Naval Record, p. 295.

- ^ David B. Woolner, Warren F. Kimball, David Reynolds: FDR's World: War, Peace, and Legacies (Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), p.70.

- ^ Borneman. Page 463.

- ^ a b "Sea Classics. Mike Coppock. September 2007. ''ERNEST J. KING: WWII'S SALTIEST SEA DOG?'' page 5". Findarticles.com. Retrieved 2013-03-20.

- ^ Gannon, Michael (1990). Operation Drumbeat. Harper. pp. 388–389 & 414–415. ISBN 0-06-092088-2.

- ^ "Sea Classics. Mike Coppock. September 2007. ''Ernest J. King: WWII'S Saltiest Sea Dog?'' page 6". Findarticles.com. Retrieved 2013-03-20.

- ^ Skates, John Ray (2000). The Invasion of Japan: Alternative to the Bomb. University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 0-87249-972-3.

- ^ Buell, Master of Sea Power, 1980, p. 223.

- ^ Buell, Master of Sea Power, 1980, p. 573.

- ^ Heinl, Robert (1966). Dictionary of Military and Naval Quotations. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. p. 258. ISBN 0-87021-149-8.

- ^ Clay Blair (2000). Hitler's U-Boat War: The Hunters, 1939–1942. Random House Digital, Inc. pp. 653–54.

- ^ Graybar, Lloyd J. (1996). Quarterdeck and Bridge: Two Centuries of American Naval Leaders. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-096-7.

- ^ Morison, Samuel Eliot (1947). History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Vol. I: The Battle of the Atlantic: 1939–1943. Little, Brown and Company. pp. 135–148. ISBN 0-316-58311-1.

- ^ Timothy J. Ryan and Jan M. Copes To Die Gallantly – The Battle of the Atlantic, 1994 Westview Press, Chapter 7.

- ^ Drawn from Section III. THE CHIEF OF NAVAL OPERATIONS—HIS STAFF AND DUTIES; “PROCEEDINGS OF HEWITT INQUIRY”; http://www.ibiblio.org/pha/pha/narrative/

- ^ Vessels records drawn from http://www.navsource.org/archives/12/01idx.htm ; List of patrol vessels of the United States Navy#SC.2C Submarine Chaser ; https://www.uscg.mil/history/cutters/docs/Flynn_USCG-W-Numbers2014.pdf ; http://www.navsource.org/archives/11/19idx.htm ; http://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs.html; http://www.uboatarchive.net/ ; https://www.fold3.com/browse/251/hsEUS91acSooI8J03phoCCIMq0P0Jm5gE ; http://ww2db.com/ship.php?list=D ; unique vessel histories in https://en.wikipedia.org and https://www.uscg.mil/history/AssetsIndex.asp .

- ^ http://www.navsource.org/Naval/usf05.htm plus references as noted in footnote #37

- ^ “U. S. NAVY BUILDING PROGRAMS DURING WORLD WAR II: FY 1939-41”; http://shipscribe.com/shiprefs/usnprog/fy3941.html

- ^ Drawn from the “Dictionary of American Naval Aviation Squadrons Volume 2 The History of VP, VPB, VP(H) and VP(AM) Squadrons”, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/naval-aviation-history/dictionary-of-american-naval-aviation-squadrons-volume-2.html and “Location of U.S. Naval Aircraft, World War II” » 1942, http://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/naval-aviation-history/location-of-us-naval-aircraft-world-war-ii/1942.html

- ^ Drawn from “AAF ANTISUBMARINE COMMAND”, http://www.uboatarchive.net/AAF/AAFHistory.htm

- ^ Drawn from “US Military Personnel (1939-1945)”,http://www.nationalww2museum.org/learn/education/for-students/ww2-history/ww2-by-the-numbers/us-military.html

- ^ Drawn from “Imperial Japanese Navy Battle Order – 1941”, http://pacific.valka.cz/forces/ijn/1941.htm

- ^ Gannon, Operation Drumbeat, 1990, pp. 391, 414–415.

- ^ Buell ch 22

- ^ Buell ch 30

- ^ Lord Ismay, The Memoirs of General Lord Ismay (1974) p. 253

- ^ Morison, Samuel Eliot (1957). History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Vol. XI: Invasion of France & Germany: 1944–1945. Little, Brown and Company. pp. 13–14. ISBN 0-316-58311-1.

- ^ Pogue, Forrest C. (1973). George C. Marshall: Organizer of Victory 1943–1945. Viking Adult. p. 305. ISBN 0-670-33694-7.

- ^ Bowen, James. Despite Pearl Harbor, America adopts a 'Germany First' strategy. The Pacific War from Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal. Pacific War Historical Society.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Simkin, John. "Ernest King". Spartacus Educational. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

- ^ Gray, Anthony W., Jr. (1997). "Chapter 6: Joint Logistics in the Pacific Theater". In Alan Gropman (ed.). The Big 'L' — American Logistics in World War II. Washington, D.C.: National Defense University Press. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Captain McVay". USS Indianapolis.org. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

- ^ Buell, Master of Sea Power, 1980, pp. 12, 17, 26.

- ^ Buell, Master of Sea Power, 1980, pp. 56, 452.

Bibliography

- Borneman, Walter R. (2012). The Admirals: Nimitz, Halsey, Leahy and King – The Five-Star Admirals Who Won the War at Sea. New York: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-09784-0.

{{cite book}}:|format=requires|url=(help) - Buell, Thomas B. (1995). Master of Sea Power: A Biography of Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-092-4.

- Gannon, Michael (1991). Operation Drumbeat. New York: Harper Collins. ISBN 0-06-092088-2.

- Jordan, Jonathan W. (2015), American Warlords: How Roosevelt's High Command Led America to Victory in World War II (NAL/Caliber 2015).

- King, Ernest; Whitehill, Walter Muir (1952). Fleet Admiral King: A Naval Record. New York City: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-7858-1302-0.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1947). Volume I. The Battle of the Atlantic, September 1939 – May 1943. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 0-7858-1302-0.

External links

- "Fleet Admiral Ernest Joseph King". Naval Historical Center, Department of the Navy. 1 June 1996. Retrieved 2007-12-30. Ernest King's biography on official U.S Department of the Navy website.

- O'Connor, Jerome (February 2004). "FDR's Undeclared War". Naval History magazine. U.S. Naval Institute. Retrieved 2007-12-30. An article documenting the "sons of bitches" quote and other relevant facts.

- 24 Armed Trawlers of the RNPS 'Churchill's Pirate's' were sent to protect the US coast in 1942.

- Ernest J. King Papers 1897-1981 (bulk 1897-1953), MS 437 held by Special Collections & Archives, Nimitz Library at the United States Naval Academy

- 1878 births

- 1956 deaths

- American 5 star officers

- American military personnel of World War I

- United States Navy World War II admirals

- Burials at the United States Naval Academy Cemetery

- Chiefs of Naval Operations

- Naval War College alumni

- United States Naval Academy alumni

- United States Navy admirals

- United States Naval Aviators

- People from Lorain, Ohio

- Recipients of the Navy Cross (United States)

- Congressional Gold Medal recipients

- Recipients of the Croix de guerre (Belgium)

- Recipients of the Croix de guerre 1939–1945 (France)

- Recipients of the Navy Distinguished Service Medal

- Knights Grand Cross of the Order of Orange-Nassau

- Honorary Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath

- Grand Croix of the Légion d'honneur

- Recipients of the Order of the Sacred Tripod

- Recipients of the Military Order of Italy

- Recipients of the Order of Abdon Calderón

- Grand Crosses of the Order of George I

- Grand Officers of the Order of the Crown (Belgium)

- Anti-British sentiment