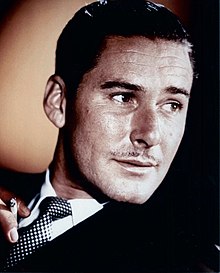

Errol Flynn

Errol Flynn | |

|---|---|

Errol Flynn c.1940 | |

| Born | Errol Leslie Thomson Flynn[1] 20 June 1909[1] |

| Died | 14 October 1959 (aged 50) Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada |

| Cause of death | Heart attack (or pulmonary embolism) |

| Resting place | Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Glendale, California |

| Education | The Hutchins School |

| Occupation | Actor |

| Years active | 1932–1959 |

| Children | Sean (born 31 May 1941; disappeared 6 April 1970) Deirdre (born 1945) Rory (born 1947) Arnella Roma (1953–98) |

Errol Leslie Thomson Flynn (20 June 1909 – 14 October 1959)[1] was an Australian-American actor.[2] He was known for his romantic swashbuckler roles in Hollywood films and his playboy lifestyle. He became a naturalized American citizen in 1942.[3]

Early life

Errol Flynn was born on 20 June 1909 in Hobart, Tasmania, where his father, Theodore Thomson Flynn, was a lecturer (1909) and later professor (1911) of biology at the University of Tasmania. Flynn was born at the Queen Alexandra Hospital in Battery Point. His mother was born Lily Mary Young, but dropped the first names Lily Mary shortly after she was married and changed her name to Marelle.[4] Flynn described his mother's family as "seafaring folk"[5] and this appears to be where his lifelong interest in boats and the sea originated. Despite Flynn's claims, the evidence indicates that he was not descended from any of the Bounty mutineers.[6][7] Married at St. John's Church of England, Birchgrove, Sydney, on 23 January 1909,[8][9] both of his parents were native-born Australians of Irish, English, and Scottish descent.[10] After early schooling in Hobart, from 1923 to 1925 Flynn was in England receiving his education at South-West London College, a private boarding school in Barnes, London,[11] and in 1926 returned to Australia to attend Sydney Church of England Grammar School (Shore School)[12] where he was the classmate of future Australian Prime Minister, John Gorton.[13] He concluded his formal education with being expelled from Shore for theft,[14] and—according to his own account—having been caught in a romantic assignation with the school's laundress.[15] After being dismissed from a job as a junior clerk with a Sydney shipping company for pilfering petty cash, he went to Papua New Guinea at the age of eighteen, seeking and failing to find his fortune in tobacco planting and metals mining. He spent the next five years oscillating between the New Guinea frontier territory and Sydney.[16]

Actor

In early 1933, Flynn appeared as an amateur actor in the Australian film In the Wake of the Bounty, in the lead role of Fletcher Christian. Later that year he headed back to England intent upon pursuing a career in acting, and shortly after arriving secured a job with the Northampton Repertory Company at the town's Royal Theatre (now part of Royal & Derngate), where he worked and received his training as a professional actor for seven months. (Northampton's art-house cinema, the Errol Flynn Filmhouse, is named after him).[17] He also performed at the 1934 Malvern Festival and in Glasgow and London's West End fleetingly.[18]

In 1934, Flynn was dismissed from Northampton Rep. after a violent fracas with a female stage manager, which involved her being tumbled down a stairwell, and he headed to Warner Brothers' Teddington Studios in Middlesex where he had worked briefly as an extra (actor) in the movie I Adore You before going to Northampton.[19] With his new-found acting skills he was cast as the lead in Murder at Monte Carlo (currently a lost film),[20] during the filming of which he was signed by Warner Bros. and emigrated to America as a contract actor.

Hollywood career

Flynn was an overnight sensation in his first starring role soon after arriving in Hollywood,[21] Captain Blood (1935). Quickly typecast as a swashbuckler, he followed it with a succession of films over the next six years that re-invented the sophistication of the action-adventure genre, most of them under the direction of Michael Curtiz, viz., The Charge of the Light Brigade (1936),The Prince and the Pauper (1937), The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938; his first Technicolor film), The Dawn Patrol (1938), Dodge City (1939), The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex (1939) and The Sea Hawk (1940).

Working throughout his career with a cross-section of Hollywood's best fight arrangers, Flynn became noted for his fast-paced sword fights as seen in The Adventures of Robin Hood, The Sea Hawk and Captain Blood.[22] He also showed an acting range beyond purely action-adventure roles, both at light contemporary social comedy via performances in The Perfect Specimen (1937) and Four's a Crowd (1938), and melodrama in The Sisters (1938).

Flynn co-starred with Olivia de Havilland a total of eight times, and together they made the most successful on-screen romantic partnership in Hollywood in the late 1930s-early '40s in Captain Blood (1935), The Charge of the Light Brigade (1936), The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938), Four's a Crowd (1938), Dodge City (1939), The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex (1939), Santa Fe Trail (1940), and They Died with Their Boots On (1941). While Flynn acknowledged his personal attraction to de Havilland, assertions by film historians that they were privately romantically involved during the filming of Robin Hood[23] have been refuted by de Havilland. In an interview for Turner Classic Movies she said that their relationship was platonic, primarily because Flynn was already married to Lili Damita.

During the shooting of The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex (1939) Flynn was co-starred for a second time with Bette Davis, but their personal relationship was quarrelsome offscreen, causing Davis allegedly to slap him across the face far harder than necessary while filming a scene. Flynn thought that the cause of Davis' wrath was her being romantically interested in him, a feeling that was not reciprocated on his part.[24] Other reports said Davis was upset to be sharing equal billing with a man she thought was not a real actor but just playing the same dashing adventurer time after time. Olivia de Havilland recounted a story where she visited Davis and they watched a private copy of Elizabeth and Essex; halfway through Davis brought her hand crashing down on her chair arm rest and declared, "Damn it! The man could act!"

In 1940, he was voted the fourth most popular star in the US according to Variety and the seventh most popular in Britain, and was at the zenith of his career.[25][26]

Flynn was a member of the Hollywood Cricket Club with David Niven, and a talented tennis player on the California Club circuit. His suave, debonair, and devil-may-care attitude toward both women and life has been immortalised in the English language by author Benjamin S. Johnson as, "Errolesque," in his treatise on the subject, An Errolesque Philosophy on Life.[27]

When Flynn became a naturalized American citizen on 15 August 1942 he also became eligible for the military draft, as the United States had entered World War II eight months earlier. Grateful to the country that had given him fame and wealth,[28] he attempted to join the armed services but he had several health problems, his heart was enlarged, with a murmur, and he had already suffered at least one heart attack; he had recurrent malaria (contracted in New Guinea), chronic back pain (for which he self-medicated with morphine and later, with heroin), lingering chronic tuberculosis, and numerous venereal diseases. Flynn, famous for his athletic roles and promoted as a paragon of male physical perfection, was classified 4-F – unqualified for military service because of not meeting the minimum physical fitness standards.[28][29] This created a public image problem for both Flynn and Warner Brothers as he was often criticized for his failure to enlist in the Armed Forces for war service as many other Hollywood actors of service age had, and yet while not apparently enlisting he continued to play war heroes in flag-waver productions such as Dive Bomber (1941), Desperate Journey (1942) and Objective Burma (1945). The Studio's failure to counter the criticism was due to a decision professionally to conceal the state of Flynn's health as he was an expensive asset – in the late 1940s his fee was $200,000 a film.[30]

After WWII the taste of the American moviegoing audience changed from its pre-war cosmopolitan interest in European-themed material and the English history-based escapist epics that Flynn had excelled at, to more gritty urban realism and film noir reflecting modern American life, and more domestically sourced subject-matter generally. Flynn, having tried unsuccessfully to make the transition with productions like Uncertain Glory (1944) and Cry Wolf (1947), and backed into an artistic corner of relying on increasingly passe Westerns such as Silver River (1948) (in which he showed his frustration with increasingly disruptive behavior on set) and Montana (1950), found himself released from his primary Warner Bros Studio contract in 1950 by Jack Warner in a stable-clearing of 1930s glamor generation stars.[24] This essentially marked the end of Flynn's Hollywood career and the money that went with it, and his descent financially and physically after it was rapid.

After Hollywood

In the 1950s, after losing his savings from the Hollywood years in a series of financial disasters, one of which was The Story of William Tell (1954),[24] he spent his time sailing aimlessly around the Western Mediterranean and its ports aboard his yacht Zaca, becoming a parody of himself with heavy alcohol use leaving him prematurely aged and overweight, and staving off financial ruin by performing in forgettable productions such as King's Rhapsody (1955) in the UK's failing movie industry (which he had attempted to return to after Hollywood's door had closed), abortive attempts or commercially unsuccessful self-production in Europe, Hello God (1951), Crossed Swords (1954), occasional roles in also-ran Hollywood movies such as Mara Maru (1952), Istanbul (1957) and television appearances.[31] As early as 1952 he had been seriously ill with hepatitis resulting from liver damage.[32] In 1956 he presented and sometimes performed in the television anthology series The Errol Flynn Theatre that was filmed in England. His acting career received a brief flare of interest once more in response to his appearance in The Sun Also Rises (1957), and in Too Much, Too Soon (1958), which had, perhaps, more to do with an audience curious to see evidence of the sensationalist stories that they had read in the press intermittently through the decade about Flynn's physical deterioration than the quality of these productions themselves. On the back of the publicity about his performance in The Sun Also Rises he made a fleeting return to Hollywood mainstream film making in The Roots of Heaven (1958). Flynn and Beverly Aadland met with Stanley Kubrick to discuss appearing together in Lolita, but nothing came of it.[33] Flynn went to Cuba in late 1958 to film the self-produced b-movie Cuban Rebel Girls and met Fidel Castro, and was initially an enthusiastic supporter of the Cuban Revolution. He narrated a short film titled Cuban Story: The Truth About Fidel Castro Revolution (1959), his last known work as an actor.[34]

Writing

Beam Ends (1937), Flynn's first published book, was an autobiographical account of his sailing experiences as a youth around Australia.

Flynn went to Spain in 1937 as a war correspondent to report for the United States during the Spanish Civil War.[35]

In 1946, he published the adventure novel Showdown.

Sundry newspaper and magazine articles, including some written for the New York Journal American by Flynn documenting his time in Cuba with Fidel Castro and his rebels went unpublished, and were to remain missing until 2009, when they were discovered in the University of Texas at Austin's Center for American History.[36]

His final book My Wicked, Wicked Ways was written between August and October 1958 with the aid of ghostwriter Earl Conrad, as Flynn was suffering from depression and alcoholism at that time, and had lost the discipline to write. Published shortly after his death, the book contains scant details of his Hollywood movie career, concentrating instead mainly on the story of his life apart from it, with odd scandalous paragraphs thrown in for shock value, which caused the inevitable media uproar upon publication, but doing no harm at all to its sales figures. In the view of one literary critic the book "remains one of the most compelling and appalling autobiographies written by a Hollywood star, or anyone else for that matter".[37] As a nod to the expression "in like Flynn" (popularly believed to reference his ease with women), Flynn wanted to call the book In Like Me, but the publisher refused.[38] In 1985 CBS produced a television film based on the book.

Personal life

Lifestyle

Flynn had a reputation for womanizing, hard drinking, and for a while in the 1940s, narcotic abuse. His lifestyle caught up with him in public in 1942 when two underage girls, Betty Hansen and Peggy Satterlee, accused him of statutory rape,[39] alleging that the event occurred at the Bel Air, Los Angeles home of Flynn's friend Frederick McEvoy.[40] The scandal received immense press attention with many of Flynn's movie fans refusing to accept that the charges were true (one such group that publicly organized to this end was "The American Boys' Club for the Defense of Errol Flynn (ABCDEF)" who counted in its number William F. Buckley, Jr.),[41] taking the image that they had of Flynn's screen persona as a reflection of his actual character in real life. The trial took place over January and February 1943, and Flynn was acquitted after a successfully aggressive defense by his lawyer castigated the accusing girls' morals and characters. Although Flynn was acquitted of the charges, the trial's sexually lurid nature played out day by day by the media, created a notorious public reputation of Flynn as a ladies' man, and permanently damaged his screen image as an idealized romantic lead player, which Warner Bros had expended much time and resources establishing in the eyes of female moviegoing audiences.

Marriages and family

Flynn was married three times: to actress Lili Damita from 1935 until 1942 (one son, Sean Flynn, born 1941, reported missing in Cambodia in 1970 and presumed dead); to Nora Eddington from 1944 until 1949 (two daughters, Deirdre born 1945 and Rory born 1947); and to actress Patrice Wymore from 1950 until his death (one daughter, Arnella Roma, 1953–98). In Hollywood, he tended to refer to himself as Irish rather than Australian (his father Theodore Thomson Flynn had been a biologist and a professor at the Queen's University of Belfast in Northern Ireland during the latter part of his career). After quitting Hollywood Flynn lived with Wymore in Port Antonio, Jamaica in the early 1950s. He was largely responsible for developing tourism to this area, and for a while owned the Titchfield Hotel, which was decorated by the artist Olga Lehmann. He also popularized trips down rivers on bamboo rafts.[42]

Flynn was a longtime friend of the painter Boris Smirnoff, who painted his portrait several times, as well as those of Lili Damita, Patrice Wymore and celebrity friends such as Edward G. Robinson, Jean Harlow, Norma Shearer and Barbara Stanwyck.[43]

The gossips took note of his close friendships with Marlene Dietrich, Dolores del Río and Carole Lombard. Lombard is said to have resisted his advances. She had already met and fallen in love with Clark Gable, but she liked Flynn and invited him to her extravagant soirees.[44]

In the late 1950s, Flynn met and courted the 15-year-old Beverly Aadland at the Hollywood Professional School, casting her in his final film, Cuban Rebel Girls (1959). According to Aadland, he planned to marry her and move to a new house in Jamaica but he died of a heart attack before this came to pass.

His only son, Sean, an actor and later a noted war correspondent, disappeared in Cambodia in 1970 during the Vietnam War while working as a freelance photojournalist for Time magazine.[45] Sean was presumed dead in 1971, probably murdered by the Khmer Rouge. In 1984, he was officially declared dead in a granted petition of declaration sought by his mother, Lili Damita. Sean's life was recounted in Inherited Risk by Jeffrey Meyers (Simon & Schuster), and he is also mentioned on page 194 in the Colleagues section of Dispatches by Michael Herr.

Flynn's daughter Rory has one son, Sean Rio Flynn, named after her half-brother. He is an actor.[46] Rory Flynn has written a book about her father entitled The Baron of Mulholland: A Daughter Remembers Errol Flynn.

Death

Flynn, in financial difficulties, flew to Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, on 9 October 1959, to try to lease his yacht Zaca to the businessman George Caldough. After spending several days at Caldough's home at 1026 Eyremont Drive, on 14 October Caldough was driving him back to the airport for a Los Angeles-bound flight when Flynn began complaining of back and leg pains, which had been getting worse for two days. He was taken to the Vancouver home of Caldough's friend, Dr. Grant Gould, at Apartment No. 201, 1310 Burnaby Street, seeking pain-killing medication before the flight. Flynn had difficulty negotiating the stairs to the apartment as his legs were troubling him and was in considerable discomfort, but in good spirit, and after receiving a pain relief injection for what the doctor diagnosed as the symptoms of degenerative disc disease (Flynn was suffering from spinal osteoarthritis at this time) Flynn began regaling those present with extended stories about his life, but refused a drink when offered it. After receiving a leg massage and manipulation while lying on the floor of the apartment's bedroom the doctor suggested that he rest the leg there for a while before attempting to walk on it again, Flynn responding that he felt "ever so much better." At this point, he was left on his own on the bedroom's floor to rest while the doctor retired to an adjacent room to re-join the other members of the small traveling party Flynn had arrived with consisting of Beverly Aadland, Caldough and his wife; also present were two friends of the doctor's – Mr. and Mrs. A.D. Cameron – whose social visit had been interrupted by Flynn's impromptu medical stop-over. After 20 minutes (6:45 P.M.) Aadland checked in on Flynn and discovered him not responsive or breathing; he had suffered a heart attack and was unconscious. Despite receiving immediate emergency medical treatment from the doctor and a swift transferral to Vancouver General Hospital by ambulance, he did not regain consciousness and was pronounced dead there at 7:45 P.M.[47] There are many conspiracy theories about Flynn's death on the Internet. However, this account of his death appears to be accurate as Flynn's personal lawyer, Justin M Golenbock, related an almost identical story of his death to his children in the late 1960s. The cause of death, based on this story, was most likely pulmonary embolism (and not a heart attack) caused by a deep venous thrombosis in one or both of his legs.

According to the Vancouver Sun (16 December 2006), "When Errol Flynn came to town in 1959 for a week-long binge that ended with him dying in a West End apartment, his local friends propped him up at the Hotel Georgia lounge so that everyone would see him." The story is a myth; immediately following the death the body was turned over to the Vancouver Coroner's Office which performed an autopsy, and then legally released to the next of kin for dispatch by railway transit to California. The results of the autopsy revealed a number of ailments including heart disease and degeneration and cirrhosis of the liver.[48] Years of alcoholism had apparently taken a toll on Flynn's body and an unnamed official from the Coroner's Office said it was that "of a tired old man – old before his time, and sick."[48]

Flynn's body was buried in Forest Lawn Memorial Park Cemetery, in Glendale, California.[49] Both of his parents survived him.

Film portrayals

- Duncan Regehr portrayed Flynn in a 1985 American TV movie My Wicked, Wicked Ways, loosely based on Flynn's autobiography of the same name.

- Guy Pearce played Errol Flynn in the 1996 Australian film Flynn, which covers Flynn's youth and early manhood, ending before the start of his Hollywood career.

- Flynn was portrayed by Jude Law in Martin Scorsese's 2004 film The Aviator.

- Kevin Kline played Flynn in a movie about his final days, The Last of Robin Hood, made in 2013.[50]

- The character of Alan Swann, portrayed by Peter O'Toole in the 1982 film My Favorite Year, was based on Flynn.[51]

- The character of Neville Sinclaire (portrayed by Timothy Dalton in the 1991 film The Rocketeer [based on the graphic novel by Dave Stevens]) is based on Flynn, with his being a Nazi agent being based on speculations made in Charles Higham's book Errol Flynn, the Untold Story.

Posthumous allegations

In 1961, Florence Aadland co-authored with Tedd Thomey The Big Love, a book alleging Flynn was involved in a sexual relationship with her 15-year-old daughter, actress Beverly.[52][53] It was later made into a play starring Tracey Ullman.[54][55]

Charles Higham allegations

In 1980, author Charles Higham published a controversial biography, Errol Flynn: The Untold Story, in which he alleged that Flynn was a fascist sympathiser who spied for the Nazis before and during World War II, and also that he was bisexual.[56][57] Higham did confess to the New York Times, however, that he had no documents proving Flynn was a Nazi agent.[58] Flynn's ex-wife Nora Eddington Black denounced the allegations and members of Flynn's family subsequently attempted to sue Higham and his publisher Doubleday for libel, but since the actor had died in 1959 the suit was dismissed.[59][60]

Other biographers accused Higham of altering FBI documents to sustain his charges against Flynn.[61] That Flynn was bisexual was also claimed by David Bret in Errol Flynn: Satan's Angel (2000), although Bret denounced the Nazi claims.

Flynn's former housemate David Niven criticised Charles Higham for his claims in 1980; Higham responded that Niven was ignorant of his friend's activities.[62]

In a 1982 interview with Penthouse magazine, Ronald DeWolf, previously known as L. Ron Hubbard Jr, claimed that his father had a strong friendship with Flynn, who was considered a family friend to the point of being looked upon as an adoptive father to DeWolf. He claimed Flynn and his father were alike, and engaged in various illegal activities together, including indulging in sexual acts with young underage girls and also drug smuggling. Flynn, however never became a practitioner of Hubbard's religious group, Scientology.[63]

In 2000, Higham wrote an article that also claimed that Flynn was previously accused of sympathising with Adolf Hitler based on his association with Dr. Hermann Erben, an Austrian who served in the German military intelligence. Unreleased MI5 files held by the British Home Office were claimed in 2000 to demonstrate Flynn worked for the Allies during the war.[64] Flynn offered to spy on Ireland for America during the war but was turned down because of FDR's fear that he sympathised with the Nazis.[65]

Subsequent biographies – notably Tony Thomas' Errol Flynn: The Spy Who Never Was (Citadel, 1990) and Buster Wiles' My Days With Errol Flynn: The Autobiography of a Stuntman (Roundtable, 1988) – have rejected Higham's claims as pure fabrication. Flynn's political leanings, say these biographies, appear to have been leftist: he was a supporter of the Spanish Republic in the Spanish Civil War and of the Cuban Revolution, even narrating a documentary titled Cuban Story shortly before his death. Flynn also wrote, financed and starred in the film Cuban Rebel Girls in which his character helps Castro's revolution. Flynn defended his visit to Cuba in an appearance on a Canadian Broadcasting Corp. (CBC) television show Front Page Challenge early in 1959. According to his autobiography, he considered Fidel Castro a close personal friend and drinking partner.[citation needed]

In June 2013, it was discovered that Errol Flynn had an unpaid debt to the Northampton menswear shop, Montague Jeffery.[66]

Posthumous cultural references

- Iron Man debuted in Tales of Suspense #39 (March 1963), published by Marvel Comics. Comic book artist Don Heck based Tony Stark's look on Errol Flynn.

- The 1965 Marvel Comics character Fandral, a companion of the Norse God Thor and a member of the Warriors Three, was based on the likeness of Flynn by co-creator Stan Lee.[67] Actor Joshua Dallas, who played the character in Thor, based his portrayal on Flynn.[68]

- According to artist Howard Chaykin, his character Ironwolf was based on Errol Flynn.

- In 1976, British rock quartet 10cc recorded a song, "Don't Hang Up," written by band members Kevin Godley and Lol Creme, for their How Dare You album. The song references Flynn in the lyric line, "I know I never had the style or the dash of Errol Flynn/but I love you."

- Errol Flynn's life was the subject of the opera Flynn (1977–78) by British composer Judith Bingham. The score is titled: Music-theatre on the life and times of Errol Flynn, in three scenes, three solos, four duets, a mad song and an interlude.[69]

- "Errol" was the title of a 1981 hit pop song by the band Australian Crawl. It appeared on their album Sirocco, which was itself named after Flynn's yacht.[70]

- Roman Polanski's 1986 film, Pirates was intended to pay homage to the beloved Errol Flynn swashbucklers of his childhood.[71]

- In 1989 UK rock band "The Dogs D'amour" release an album titled "Errol Flynn" that charted at No. 26 on the UK charts.

- In 2005, a small waterfront reserve in Sandy Bay, a suburb of Flynn's hometown of Hobart, was renamed from Short Beach to the "Errol Flynn Reserve".[72]

- The Pirate's Daughter, a 2008 novel by Margaret Cezair-Thompson, is a fictionalised account of Flynn's later life.[73]

- In June 2009 the Errol Flynn Society of Tasmania Inc. organised the Errol Flynn Centenary Celebration, a 10-day series of events designed to celebrate the 100th anniversary of his birth[74] On the actual centenary, 20 June 2009, his daughter Rory Flynn unveiled a star with his name on the footpath outside Hobart's heritage State Cinema.[75]

- In 2009, the Port Antonio mega-yacht marina in the northeastern coast of Jamaica underwent a name change to the Errol Flynn Marina.[76][77]

- The 2010 novel Errol, Fidel and the Cuban Rebel Girls by Boyd Anderson is a fictionalised account of the last year of Flynn's life in Cuba.[78]

- Jay Electronica song "2-Step" Lyrics: "Chillin' in the circle, Errol Flynnin' it up" [79]

- In the 1991 film The Rocketeer, the characterization of Neville Sinclair was inspired by Flynn, or rather by the image of Flynn that had been popularized by Charles Higham's unauthorized and fabricated biography of the actor,[80] in which he asserted that Flynn was, among other things, a Nazi spy. The film's Neville Sinclair is, like Higham's Flynn, a movie star known for his work in swashbuckler roles, and who is secretly a Nazi spy. Because Higham's biography of Flynn was not refuted until the late 1980s, the image of Flynn as a closet Nazi remained current all through the arduous process of writing and re-writing the script.[81]

- "The trouble was started by a young Errol Flynn" is a line in the song Blood on the Rooftops from the 1976 Genesis album, Wind and Wuthering.

- "Errol Flynn" is the name of a song by Australian indie band Jinja Safari.

- In the fourth episode of the second season of Breaking Bad, Walter White(Bryan Cranston) makes a reference to Errol Flynn while discussing the nickname chosen by his son.

- In the Doctor Who episode "Robot of Sherwood", the 12th Doctor (Peter Capaldi) makes reference to having trained with Errol Flynn (among others) in the art of swordplay while fighting Robin Hood.

Bibliography

- Beam Ends (1937)

- Showdown (1946)

- Flynn, Errol. My Wicked, Wicked Ways: the Autobiography of Errol Flynn. Intro. by Jeffrey Meyers. New York: Cooper Square Press, 2003. Rpt. of My Wicked, Wicked Ways. New York: G.P. Putnam's sons, 1959. ISBN 0-8154-1250-9.

- Flynn, Errol "The Quest for an Oscar." by James Turiello, BearManor Media, Duncan, OK. 2012. ISBN 978-1-59393-695-2.

Filmography

Select radio performances

Flynn appeared in numerous radio performances:[82]

| Year | Title | Venue | Dates performed |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1937 | Captain Blood | Lux Radio Theatre | 22 February[83] |

| 1937 | British Agent | Lux Radio Theatre | 7 June[84] |

| 1937 | These Three | Lux Radio Theatre | 6 December[85] |

| 1938 | Green Light | Lux Radio Theatre | 31 January |

| 1939 | The Perfect Specimen | Lux Radio Theatre | 2 January[86] |

| 1939 | Lives of a Bengal Lancer | Lux Radio Theatre | 10 April[87] |

| 1940 | Trade Winds | Lux Radio Theatre | 4 March[88] |

| 1941 | Virginia City | Lux Radio Theatre | 26 May[89] |

| 1941 | They Died With Their Boots On | Cavalcade of America | 17 November[90] |

| 1944 | Command Performance | Armed Forces Radio Network | 30 July[91] |

| 1946 | Gentleman Jim | Theatre of Romance | 5 February |

| 1952 | The Modern Adventures of Casanova | 22 May |

Theatre performances

Flynn appeared on stage in a number of performances, particularly early in his career:[92]

- The Thirteenth Chair – Dec 1933 – Northampton Rep

- Jack and the Beanstalk – Dec 1933 – Northampton Rep

- Sweet Lavendar – January 1934 – Northampton Rep

- Bulldog Drummond – January 1934 –Northampton Rep

- A Doll's House – January 1934 – Northampton Rep

- On the Spot – January 1934 – Northampton Rep

- Pygmalion – January–February 1934 – Northampton Rep

- Crime at Blossoms – February 1934 – Northampton Rep

- Yellow Sands – February 1934 – Northampton Rep

- The Grain of Mustard Seed – February 1934 – Northampton Rep

- Seven Keys to Baldpate – March 1934 – Northampton Rep

- Othello – March 1934 – Northampton Rep

- The Green Bay Tree – March 1934 – Northampton Rep

- The Fake – March 1934 – Northampton Rep

- The Farmer's Wife – March–April 1934 – Northampton Rep

- The Wind and the Rain – April 1934 – Northampton Rep

- Sheppey – April 1934 – Northampton Rep

- The Soul of Nicholas Snyders – April 1934 – Northampton Rep

- The Devil's Disciple – May 1934 – Northampton Rep

- Conflict – May 1934 – Northampton Rep

- Paddy the Next Best Thing – May 1934 – Northampton Rep

- 9:45 – May–June 1934 – Northampton Rep

- Malvern festival – July–August 1934 – appeared in A Man's House, History of Dr Faustus, Marvelous History of Saint Bernard, The Moon in Yellow River, Mutiny

- A Man's House – August – September1934 – Glasgow, St Martin's Lane

- Master of Thornfield – February 1958 – adaptation of Jane Eyre

References

- ^ a b c d McNulty, Thomas (2004). "One: from Tasmania to Hollywood 1909–1934". Errol Flynn: the life and career. McFarland. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-7864-1750-6.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Obituary Variety, 21 October 1959, page 87.

- ^ "In August 1942 I received my naturalisation papers. I was an American citizen." in: Flynn, My Wicked, Wicked Ways. New York 1959, p. 267

- ^ Flynn always calls her Marelle in his autobiography.

- ^ Flynn, My Wicked, Wicked Ways, p.33.

- ^ Fasano, Debra (2009). Young Blood – The Making of Errol Flynn. ISBN 978-0-9806703-0-1.

- ^ Flynn, My Wicked, Wicked Ways, p.33

- ^ "Flynn, Errol Leslie (1909–1959)". Australian Dictionary of Biography Online. Retrieved 7 June 2008.

- ^ "Biography for Errol Flynn". imdb.com. Retrieved 24 December 2008.

- ^ Flynn, My Wicked, Wicked Ways, p.25.

- ^ Bardrick, Ajax (2008) 'Errol Flynn's Barnes Period', published by 'the-vu'

- ^ Moore, John Hammond: "Young Errol Flynn before Hollywood", 1975. ISBN 0-207-13158-9

- ^ Shaw, John (22 May 2002). "Sir John Gorton, 90, Australian Who Vetoed Himself as Premier". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ Moore, John Hammond 'The Young Errol Flynn Before Hollywood' (2nd Edition, 2011, Trafford Publishing),

- ^ Flynn, Errol 'My Wicked, Wicked Ways' (Pub. 1959)

- ^ Moore, John Hammond 'The Young Errol Flynn Before Hollywood' (2nd Edition, Trafford Publishing, 2011)

- ^ "New art-house cinema to be named after Hollywood legend Errol Flynn – Northampton Chronicle and Echo". northamptonchron.co.uk. Retrieved 20 February 2014.

- ^ Connelly, Gerry (1998). Errol Flynn in Northampton. Domra Publications. ISBN 978-0-9524417-2-4.

- ^ Connelly, Gerry (1998) 'Errol Flynn in Northampton'

- ^ "Murder at Monte Carlo | BFI Most Wanted BFI National Archive". BFI. 23 December 2010. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- ^ Caterson, Simon, "Errol Flynn, man in tights", On Line Opinion, 10 June 2009. Retrieved 14 June 2012 http://www.onlineopinion.com.au/view.asp?article=9021&page=0

- ^ "TheOneRing.net, TORn exclusive with 'Reclaiming The Blade,' Director, May 15th, 2009 by MrCere". Theonering.net. 15 May 2009. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ Rudy Behlmer in the Special Edition release of Robin Hood (2003)

- ^ a b c Flynn, Errol (1959) 'My Wicked, Wicked Ways'

- ^ "FILM WORLD". The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879–1954). Perth, WA: National Library of Australia. 14 February 1941. p. 16. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ "FILM WORLD". The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879–1954). Perth, WA: National Library of Australia. 21 February 1941. p. 14. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ My Wicked, Wicked Ways (essay)

- ^ a b Basinger, Jeanine: The Star Machine, p. 247.

- ^ Thomas, Tony Errol Flynn: The Spy Who Never Was

- ^ "STAR SYSTEM 'ON THE WAY OUT'". The Mail (Adelaide, SA : 1912–1954). Adelaide, SA: National Library of Australia. 14 October 1950. p. 8 Supplement: Sunday Magazine. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ^ 'Errol Flynn', 'Secret Lives Series' (1996), documentary made for Channel 4 Television by Hart-Ryan Productions, England.

- ^ Flynn, Errol My Wicked, Wicked Ways (1959) p. 14

- ^ Robert Osborne (5 September 2007). "Errol Flynn's daughter remembers notorious dad". Reuters. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ "The Truth About Fidel Castro Revolution". IMDB. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ Tasmanian Devil: The Fast and Furious Life of Errol Flynn Retrieved 23/05/12

- ^ Errol Flynn's Cuban adventures Retrieved 23/05/12

- ^ Caterson, Simon, "Genius for living driven by lust for death", Australian Literary Review, 3 June 2009. Retrieved 6 June 2009 http://www.theaustralian.news.com.au/story/0,25197,25542210-25132,00.html

- ^ ERROL FLYNN PROFILE Retrieved 23/05/12

- ^ "Statutory Rape Charges". MSNBC. 1 March 2005. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ Flynn's Host Sued For Divorce. The Advertiser. 28 October 1942. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- ^ Valenti, Peter Errol Flynn: A Bio-Bibliography

- ^ "The History of Jamaica – Captivated by Jamaica (Dr. Rebecca Tortello)". Jamaica-gleaner.com. 27 August 2002. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ Napier-Ford, Noel: Smirnoff biography for Sir Peter Michael's restaurant "The Vineyard"

- ^ Thomas McNulty Errol Flynn: The Life and Career

- ^ "Twilight of an Idol". mensvogue.com. Archived from the original on 29 December 2008. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- ^ "Sean Rio Flynn". Seanflynn.org. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ Vancouver Coroner's Office report on Errol Flynn's death

- ^ a b John Mackie, the Vancouver Sun 14 October 1959; Today in History: The Vancouver Sun, Saturday 13 October 2012, p.A2

- ^ Errol Flynn at Find a Grave

- ^ Jeff Sneider, "Kevin Kline to play Errol Flynn", Variety, 10 October 2012 accessed 23 November 2012

- ^ p.19 Film British Federation of Film Societies 1984

- ^ Smith, Jack (30 December 1985). "A few more literary favorites among the best of the firsts and the best of the lasts". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Aadland, Florence; Thomey, Tedd (1986). The Big Love (reprint ed.). Grand Central Pub. ISBN 0-446-30159-0.

- ^ Richards, David (14 April 1991). "Secret Sharers: Solo Acts in a Confessional Age". New York Times. Retrieved 15 February 2009.

- ^ Simon, John (18 March 1991). "Two from the Heart, Two from Hunger". New York Magazine. pp. 76–77. Retrieved 15 February 2009.

- ^ Higham, Charles (1980). Errol Flynn: The Untold Story. Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-13495-9.

- ^ Charles Higham "The missing Errol Flynn file", New Statesman, 17 April 2000

- ^ Biographer Charles Higham, who wrote about Errol Flynn, dies Retrieved 23/05/12

- ^ Charles Higham, Celebrity Biographer, Dies at 81 Retrieved 23/05/12

- ^ Fighting for Errol Flynn's Reputation, His Daughters Sue Over Charges He Was a Bi Spy Retrieved 23/05/12

- ^ Charles Higham, who has died aged 81, was a much-feared and notoriously bitchy celebrity biographer whose works fell squarely in the "unauthorised" category Retrieved 23/05/12

- ^ Higham, Charles. "Who's sitting on Errol Flynn's grave?" Sunday Times [London, England] 13 Jan 1980: 15. The Sunday Times Digital Archive. Web. 21 Apr 2014.

- ^ "Inside The Church of Scientology: An Exclusive Interview with L. Ron Hubbard, Jr". Penthouse. June 1983.

- ^ Bamber, David (19 June 2001). "Errol Flynn 'spied for Allies, not the Nazis'". The Daily Telegraph. UK. Retrieved 25 May 2009.

- ^ McCann, Naula (25 April 2012). "Make me a spy in Ireland says Errol Flynn". BBC. UK. Retrieved 25 May 2009.

- ^ "Errol Flynn had 'unpaid debt' to Northampton menswear shop". BBC News. 21 June 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- ^ Cooke, Jon B. (Editor); Thomas, Roy (Interviewer). "Stan the Man & Roy the Boy: A Conversation Between Stan Lee and Roy Thomas ", TwoMorrows. reprinted from Comic Book Artist No. 2. Retrieved 8 May 2011.

- ^ Weintraub, Steve (10 December 2010). "Ray Stevenson (Volstag) and Joshua Dallas (Fandril) On Set Interview THOR". Collider. Archived from the original on 5 July 2011. Retrieved 10 December 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ 'Judith Bingham in Interview', Tempo, No.58 (2004), pp.20–36

- ^ McFarlane, Ian (1999). Encyclopedia of Australian Rock and Pop (doc). Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86448-768-2. Retrieved 1 March 2008.

- ^ Pirates review by Roger Ebert, 18 July 1986

- ^ "Errol Flynn Reserve wins the duel". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 15 April 2005. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Jamaica beguiles as fact inspires fiction

- ^ "Errol Flynn Centenary". Errol Flynn Society of Tasmania Inc. June 2009. Retrieved 19 June 2009. Be 'in like Flynn' to 10 days of events!

- ^ Cuddihy, Martin (21 June 2009). "ABC News". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ Welcome To The Errol Flynn Marina by Gareth Davis, Gleaner Writer

- ^ Celebrating With Patrice Wymore Flynn by Gareth Davis Sr, Gleaner Writer

- ^ Anderson, Boyd (2010). Errol, Fidel and the Cuban Rebel Girls. University of Queensland Press. ISBN 978-0-7022-3856-7.

- ^ "Jay Electronica – 2 Step Lyrics | Rap Genius". rapgenius.com. Retrieved 20 February 2014.

- ^ Sachs, Andrea. "Critics' Voices." Time, 5 August 1991. Retrieved: 31 October 2010.

- ^ Capshaw, Ron. "Review of: 'Errol Flynn: The True Adventures of a Real-Life Rogue', by Lincoln Hurst." Bright Lights Journal, Issue 69, August 2010 via brightlightsfilm.com, 2010.Retrieved: 1 November 2010.

- ^ 'Errol Flynn Radio Shows' at The Errol Flynn Blog

- ^ "Captain Blood" at Lux Radio Theatre on Internet Archive

- ^ "British Agent", Lux Video Theatre at Internet Archive

- ^ "These Three", Lux Radio Theatre at Internet Archive

- ^ "The Perfect Specimen" Lux Radio Theatre at Internet Archive

- ^ "Lives of a Bengal Lancer", Lux Radio Theatre at Internet Archive

- ^ "Trade Winds" Lux Radio Theatre at Internet Archive

- ^ "Virginia City", Lux Radio Theatre at Internet Archive

- ^ "They Died With Their Boots On", Cavalcade of America at Internet Archive

- ^ Errol Flynn in Command Performance at Internet Archive

- ^ Gerry Connelly, Errol Flynn in Northampton, Domra Publications, 1998.

External links

- Errol Flynn at IMDb

- Flynn, Errol (1909–1959) National Library of Australia, Trove, People and Organisation record for Errol Flynn

- Errol Flynn at the National Film and Sound Archive

- Errol Flynn's official web site, owned by daughter, Rory Flynn

- Errol Flynn centenary 1909–2009 article by Nick Thomas in Washington Post

- Profile @ Turner Classic Movies

- Errol Flynn Resource Website Flynn resource website, filmography & photographs.

- Programs and related material in the National Library of Australia's PROMPT collection

- His Wicked Wicked Ways: Flynn's 100th Birthday[dead link]

- Errol Flynn segment from The Collectors

- Errol Flynn's Cuban Adventures by BBC News

- Errol Flynn & Patrice Wymore Marry in Monaco – TCM Movie Morlocks[dead link]

- 1909 births

- 1959 deaths

- 20th-century American male actors

- American expatriates in Jamaica

- American male film actors

- American male radio actors

- American people of Australian descent

- American people of English descent

- American people of Irish descent

- American people of Scottish descent

- Australian expatriate male actors in the United States

- Australian expatriates in Jamaica

- Australian expatriates in the United Kingdom

- Australian male film actors

- Australian emigrants to the United States

- Australian people of English descent

- Australian people of Irish descent

- Australian people of Scottish descent

- Burials at Forest Lawn Memorial Park (Glendale)

- Deaths from myocardial infarction

- People educated at Sydney Church of England Grammar School

- Male actors from Hobart

- Male actors from Sydney

- Male Western (genre) film actors

- Warner Bros. contract players

- 20th-century Australian male actors