Ettore Sottsass

Ettore Sottsass | |

|---|---|

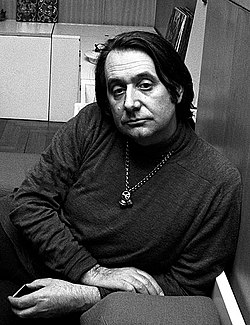

Ettore Sottsass in 1969 | |

| Born | 14 September 1917 |

| Died | 31 December 2007 (aged 90) |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Practice | Sottsass Associati |

| Buildings | Mayer-Schwarz Gallery Beverly Hills, California |

Ettore Sottsass (14 September 1917 – 31 December 2007) was an Italian architect and designer during the 20th century. His body of work included furniture, jewelry, glass, lighting, home objects and office machine design, as well as many buildings and interiors.

Early life

Sottsass was born on September 14, 1917, in Innsbruck, Austria, and grew up in Turin, where his father, also named Ettore Sottsass, was an architect.[1] The elder Sottsass belonged to the modernist architecture group Movimento Italiano per l'Architectura Razionale (MIAR), which was led by Giuseppe Pagano.

The younger Sottsass was educated at the Politecnico di Torino in Turin and graduated in 1939 with a degree in architecture. He served in the Italian military, in the Repubblica Sociale Italiana, and spent some of World War II in a prison and then in a labor camp in [Yugoslavia].[1]

Early career

After returning home, Ettore Sottsass worked as an architect with his father, often on new modernist versions of buildings that were destroyed during the war. In 1947, living in Milan, he set up his own architectural and industrial design studio,[2] where he began to create work in a variety of different media: ceramic, painting, sculpture, furniture, photography, jewelry, architecture and interior design.

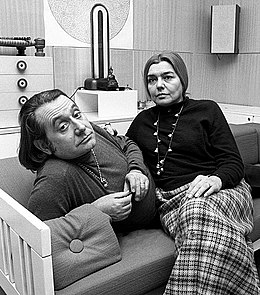

In 1949 Sottsass married Fernanda Pivano, a writer, journalist, translator and critic.[3] In 1956, Sottsass traveled to New York City and began working in the office of George Nelson. He and Pivano traveled widely while working for Nelson, and returned to Italy after a few months.

Also in 1956, Sottsass was commissioned by the American entrepreneur Irving Richards on an exhibition of his ceramics.[4]

Back in Italy in 1957, Sottsass joined Polotronova, a semi-industrial producer of contemporary furniture, as an artistic consultant[5]. Much of the furniture he worked on there influenced the design he would create later with Memphis Milano.

Olivetti

In 1958, Sottsass was hired by Adriano Olivetti as a design consultant for Olivetti, to design electronic devices and develop the first Italian mainframe computer, the Elea 9003 for which he was awarded the Compasso d'Oro in 1959. He also designed office equipment, typewriters, and furniture. There Sottsass made his name as a designer who, through colour, form and styling, managed to bring office equipment into the realm of popular culture.[6] His first typewriters, the Tekne 3 and the Praxis 48, were characterized by their sobriety and their angularity. With Perry A. King, Sottsass created the Valentine in 1969 which is considered today as a milestone in 20th century Design. Light, portable, which become a fashion accessory[6]

While continuing to design for Olivetti in the 1960s, Sottsass developed a range of objects which were expressions of his personal experiences traveling in the United States and India.[7] These objects included large altar-like ceramic sculptures and his "Superboxes", radical sculptural gestures presented within a context of consumer product, as conceptual statements.[8] Covered in bold and colorful, simulated custom laminates, they were precursors to Memphis, a movement which came more than a decade later.[9] Around this time, Sottsass said: "I didn’t want to do any more consumerist products, because it was clear that the consumerist attitude was quite dangerous."[10][11] As a result, his work from the late 1960s to the 1970s was defined by experimental collaborations with younger designers such as Superstudio and Archizoom Associati,[12] and association with the Radical movement, culminating in the foundation of Memphis at the turn of the decade.

In 1970s he designed the modular office equipment Synthesis 45.

Sottsass and Fernanda Pivano divorced in 1970, and in 1976 Sottsass married Barbara Radice, an art critic and journalist.

When Roberto Olivetti succeeded as head of the company, he named Sottsass artistic director and gave him a high salary, but Sottsass refused. Instead he created the Studio Olivetti independently, working Olivetti and became instantly the most creative international center of design associating research with creation and industrial strategy. The feeling that his creativity would have been stifled by corporate work is documented in his 1973 essay "When I was a Very Small Boy".[13]

In 1968, the Royal College of Art in London granted Sottsass an honorary doctoral degree.[14]

Throughout the 1960s, Sottsass travelled in the US and India and designed more products for Olivetti, culminating in the bright red plastic portable Valentine typewriter in 1970, Sotsass described the Valentine as "a brio among typewriters." Compared with the typical drab typewriters of the day, the Valentine was more of a design statement item than an office machine.

Memphis Group

With the rise of new groups (Global tools, Archizoom, Superstudio, UFO, Zzigurat, 9999...) the handmade appeared suddenly as the new game for experimentation, a lot of these new groups playing in this new/old path to renew creation. In October 1980, Sottsass was confronted with two proposals, one from Renzo Brugola, a dear old friend and carpenter, telling him his will "to make something together like in the good old times,” and the other one from Mario and Brunella Godani, owners of the Design Gallery Milano, who asked him to create "new furniture" for their gallery.

Ettore Sottsass founded the Memphis Group in Milan on December 11, 1980, after the Bob Dylan song "Stuck inside of Mobile with the Memphis blues again" played during the group's inaugural meeting. The group was active from 1981 to 1988.

By their second meeting in February 1981, members brought over a hundred drawings with them, outlining designs inspired by Art Deco, Bauhaus and Pop Art to create bold and colorful design.

Members

- Ettore Sottsass

- Martine Bedin

- Thomas Bley

- Andrea Branzi

- Aldo Cibic

- Massimo Iosa Ghini

- Michael Graves

- Hans Hollein

- Shiro Kuramata

- Michele de Lucchi

- Javier Mariscal

- Chung Eun Mo

- Nathalie du Pasquier

- Barbara Radice

- Maria Sanchez

- George J. Sowden

- Peter Shire

- Gerard Taylor

- Matteo Thun

- Masanori Umeda

- Marco Zanini

- Marco Zanuso

Impact

After having been successful since its first exhibition on September 18, 1981 at the gallery Arc74, bringing in more than 2500 visitors, the group was dismantled by Sottsass in 1988. Recently, there has been a revival of the group. Seen nowadays as a radical historic group, it served as inspiration for the Fall/Winter 2011-2012 Christian Dior haute couture collection and for the Fall/Winter 2015 Missoni collection.

The group most iconic work is the "Carlton" room divider designed by Sottsass in 1981.

Sottsass Associati

As the Memphis movement in the 1980s attracted attention worldwide for its energy and flamboyance, Ettore Sottsass began assembling a major design consultancy, which he named Sottsass Associati. Sottsass Associati was established in 1980 and gave the possibility to build architecture on a substantial scale as well as to design for large international industries. Besides Ettore Sottsass, the others founding members were Aldo Cibic, Marco Marabelli, Matteo Thun and Marco Zanini[15]. Later, also Johanna Grawunder, Marco Susani and Mike Ryan will join the firm. In 1985, Sottsass left Memphis to focus on the Associati.

Sottsass Associati, primarily an architectural practice, also designed elaborate stores and showrooms for Esprit, identities for Alessi, exhibitions, interiors, consumer electronics in Japan and furniture of all kinds. The studio was based on the cultural guidance of Ettore Sottsass and the work conducted by its many young associates, who often left to open their own studios. Sottsass Associati is now based in London and Milan and continue to sustain the work, philosophy and culture of the studio.

The studio works with former members of Memphis as well as with the architect Johanna Grawunder and the industrial designer James Irvine. It works for major companies like Apple, Philips, Siemens, Zanotta, Fiat, Alessi, and also realises the interior design of all the retail shops of Esprit (Esprit Holdings)

Notable achievements in design

- Valentine typewriter, Olivetti, 1969

- Superbox cabinet, Poltronova, 1966

- Ultrafragola mirror, Poltronova, 1970

- Tahiti lamp, Memphis, 1981

- Murmansk fruit bowl, Memphis, 1982

- Carlton bookcase, Memphis, 1981

- Malabar bookcase, Memphis, 1981

- Casablanca cabinet, Memphis, 1981

- Enorme phone, 1986

- Miss don't you like caviar chair, 1987

- Memories of China collection, the Gallery Mourmans, 1996

- Mandarin chair, Knoll, 1986

- Glass works for Venini

- Glass works for the CIRVA

- Twergi collection, Alessi, 1989

Notable achievements in architecture

- Fiorucci store, 1980

- Esprit showroom, Düsseldorf, 1985

- Esprit showroom, Zurich, 1985

- Esprit showroom, Hambourg, 1985

- Building, Marina di Massa, 1985

- Alessi showroom, Milan, 1985

- Wolf house, Ridgway (Colorado), 1985 with Johanna Grawunder

- Zibibbo bar, Fukuoka, 1989

- Olabuenaga house, Maui, 1989 with Johanna Grawunder

- Cei house, Empoli, 1989

- Bischofberger house, Zurich, 1989 with Johanna Grawunder

- Museum of Contemporary Art, Ravenne, 1992

- Ghella house, Roma, 1993

- Green house, London, 1993

- Motoryacht Amazon Express, 1994

- Golf and club resort, Zhaoqing, 1994

- Malpensa Airport, Milan, 1994

- Nanon house, Lanaken, 1995

- Van Impe house, Sint-Lievens-Houtem, 1996

- Alitalia waiting room, 1997

- Roppongi Island, Tokyo, 2004

- Sport house, Nanjing, 2004

Other works

As an industrial designer, his clients included Fiorucci, Esprit, the Italian furniture company Poltronova, Knoll International, Serafino Zani, Alessi and Brondi. As an architect, he designed the Mayer-Schwarz Gallery on Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills, California, with its dramatic doorway made of irregular folds and jagged angles, and the home of David M. Kelley, designer of Apple's first computer mouse, in Woodside, California. The interiors of the Malpensa Airport, in Milan, were designed by Sottsass in the late 1990s, but he did not architect the building.[16] In the mid-1990s, he designed the sculpture garden and entry gates of the W. Keith and Janet Kellogg Gallery at the campus of Cal Poly Pomona. He collaborated with well-known figures in the architecture and design field, including Aldo Cibic, James Irvine, Matteo Thun.

Sottsass created a vast body of work: furniture, jewelry, ceramics, glass, silver work, lighting, office machine design and buildings. He inspired generations of architects and designers. In 2006 the Los Angeles County Museum of Art held the first major museum survey exhibition of his work in the United States. A retrospective exhibition, Ettore Sottsass: Work in Progress, was held at the Design Museum in London in 2007. In 2009, the Marres Centre for Contemporary Culture in Maastricht presented a re-construction of a Sottsass' exhibition 'Miljö för en ny planet' (Landscape for a new planet), which took place in the National Museum in Stockholm in 1969.[8] In 2017, on the occasion of Sottsass' 100th birthday, the Met Breuer museum in New York City presented the retrospective Ettore Sottsass: Design Radical.[17]

One of his works—Telefono Enorme, designed with David M. Kelley for Brondi—is part of the MOMA Collection, as well as many drawings. Design objects and drawings by Sottsass are also in the permanent collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Design Museum in London, the Vitra Design Museum, the Brooklyn Museum, the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, the Stedelijk Museum.

In 1999, he was awarded the Sir Misha Black award and was added to the College of Medallists.[18]

Bibliography

- Hans Höger, Ettore Sottsass jr. – Designer, Artist, Architect, Wasmuth, Tübingen/Berlin 1993

- Barbara Radice, Ettore Sottsass, Electa, Milano, 1993

- F. Ferrari, Ettore Sottsass: tutta la ceramica, Allemandi, Torino, 1996

- M. Carboni (edited by), Ettore Sottsass e Associati, Rizzoli, Milano, 1999

- M. Carboni (edited by), Ettore Sottsass. Esercizi di Viaggio, Aragno, Torino, 2001

- M. Carboni e B. Radice (edited by), Ettore Sottsass. Scritti, Neri Pozza Editore, Milano 2002

- M. Carboni e B. Radice (edited by), Metafore, Skirà Editore, Milano 2002

- M. Carboni (edited by), Sottsass: fotografie, Electa, Napoli 2004

- M. Carboni (edited by), "Sottsass 700 disegni", Skirà Editore, Milano, 2005

- M. Carboni (edited by), "Sottsass '60/'70", Editions HYX, Orléans, 2006

References

- ^ a b Sudjic, Deyan (2015). Ettore Sottsass and the poetry of things. ISBN 0714869538.

- ^ Pogrebin, Robin J. (1 January 2008). "Ettore Sottsass, Designer, Is Dead at 90". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ^ Ettore Sottsass. The Telegraph. 2 January 2008

- ^ "Take Care: Ettore Sottsass and Jesse Wine". ARTUNER. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ^ "Ettore Sottsass Jr - Centro Studi Polotronova". Centro Studi Polotronova (in Italian). 1 January 1970. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ^ a b "Designer who helped to make office equipment fashionable and challenged the standard notion of tasteful interiors". Timesonline.co.uk. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- ^ Radice, Barbara (1993). Ettore Sottsass: A Critical Biography. London, Thames and Hudson.

- ^ a b "We Were Exuberant and Still Had Hope. Ettore Sottsass: works from Stockholm, 1969 – Marres Maastricht – Centre For Contemporary Culture". Marres.org. 10 January 2010. Archived from the original on 15 April 2013. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Home Content, Studio International". studio-international.co.uk. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- ^ "The most comprehensive archives of architecture and design content – Icon Magazine". iconeye.com. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "superunfoldedbox". Guykeulemans.com. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- ^ "Ettore Sottsass @ Art + Culture". Artandculture.com. 26 March 2009. Archived from the original on 20 August 2012. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "When I Was a Very Small Boy: Observatory". Design Observer. 31 December 2007. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- ^ "Ettore Sottsass". design-technology.org.

- ^ Sottsass, Ettore, ed. (1988). Sottsass Associates. New York: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc.

- ^ Muschamp, Herbert (6 July 1997). "Concerned More About People Than the Planes". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- ^ "Ettore Sottsass: Design Radical". The Metropolitan Museum of Art, i.e. The Met Museum. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- ^ "The Sir Misha Black Medal | Misha Black Awards". mishablackawards.org.uk. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

External links

- Ettore Sottsass : Designer of the world, Château de Montsoreau-Museum of Contemporary Art, 2017[1]

- Sottsass design collection and other Memphis design

- A conversation with designer Ettore Sottsass, television interview with Charlie Rose, 29 November 2004, video.

- Ettore Sottsass. Existential Design, published by Hans Höger in domusWeb, Milan 2005.

- Emeco Nine-0 by Ettore Sottsass

- The Life and Times of Ettore Sottsass

- Jennifer Kabat on Ettore Sottsass

- STORIES OF HOUSES: Ernest Mourmans' House in Belgium, by Ettore Sottsass

- Hans Höger on Ettore Sottsass: Existential Design, DomusWeb, April 2005.

- Olivetti official site

- Obituary in The Times, 2 January 2008

- Design Museum Collection

- Sottsass Associati