Europa regina

Europa regina, Latin for Queen Europe, is the map-like depiction of the European continent as a queen.[1][2] Made popular in the 1500s, the map shows Europe standing upright, with the Iberian Peninsula forming her crowned head, and Bohemia her heart.

Origins

During the European Middle Ages, maps typically adhered to the Jerusalem-centered T-O scheme, depicting Europe, Asia and Africa.[3] Separate maps of Europe were extremely rare; the only known examples are a map from Lambert of Saint-Omer's Liber Floridus, published in 1112, and a 14th-century Byzantine map.[3] The next Europe-focussed map was published by cartographer Johannes Putsch in 1537, at the beginning of the Early Modern Age.[3]

The Putsch-map was the first to depict Europe as an Europa regina,[4][3][5] with the European regions forming a female human shape with crown, sceptre and globus cruciger.[3] The map was first printed by Calvinist Christian Wechel.[6] Though much about the origination and initial perception of this map is uncertain,[5] it is known that Putsch (whose name was Latinized as Johannes Bucius Aenicola, 1516-1542)[6] maintained close relations with Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand I of Habsburg,[5][6] and that the map's popularity increased significantly during the second half of the 16th century.[5] The modern term Europa regina was not yet used by Putsch's contemporaries, who instead used the Latin phrase Europa in forma virginis ("Europe in the shape of a maiden").[6]

In 1587, Jan Bußemaker published a copper engraving by Matthias Quad, showing an adaptation of Putsch's Europa regina, as "Europae descriptio".[5] Since 1588,[5] another adaption was included in all subsequent editions of Sebastian Münster's "Cosmographia",[3][5] earlier editions had it only sometimes included.[6] Heinrich Bünting's "Itenerarium sacrae scripturae", which had a map of Europe with female features included in its 1582 edition, switched to Europa regina in its 1589 edition.[5] Based on these and other examples, the year 1587 marks the point when many publications began adopting the imagery of Europa regina.[5]

Description

Europa regina is a young, graceful woman.[7] Her crown, placed on the Iberian peninsula, is shaped after the Carolingian hoop crown.[7] France and the Holy Roman Empire make up the upper part of her body, with Bohemia being the heart.[7] Her long gown stretches to Hungary, Poland, Lithuania, Livonia, Bulgaria, Muscovy, Macedonia and Greece. In her arms, formed by Italy and Denmark, she holds a sceptre and an orb (Sicily).[7] In most depictions, Africa, Asia and the Scandinavian peninsula are partially shown,[7] as are a schematized British Isles.

Symbolism

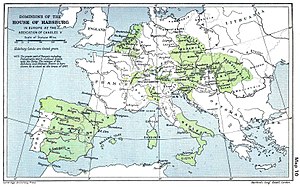

In 1537, when the Europa regina was introduced, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V of Habsburg had united the lands of the Habsburgs in his hands, including his country of origin, Spain.[6] Thus, the map is oriented westwards to have Spain as the crowned head,[6] pointing at the Habsburgs' claim to be universal emperors of Europe.[7] The most obvious connections to the Holy Roman Emperor are the Carolingian crown and the imperial insignia - sceptre and orb.[7] Another connection to Charles V is the gown, which resembles the contemporary dress code at the Habsburg court, and the face of the queen, which some say resembles Charles V's wife Isabella.[8] As in contemporary portraits of couples, Europa regina has her head turned to her right and also holds the orb with her right hand, which has been interpreted as facing and offering power to her imaginary husband, the emperor.[8]

More general, Europe is shown as the res publica christiana,[6] the united Christendom in medieval tradition,[7] and great[1] or even dominant power in the world.[8]

A third allegory is the attribution of Europe as the paradise by special placement of the water bodies.[6] As contemporary iconography depicted the paradise as a closed form, Europa regina is enclosed by seas and rivers.[6] The Danube river is depicted in a way that it resembles the course of the biblical river flowing through the paradise, with its estuary formed by four arms.[6]

That Europa regina is surrounded by water is also an allusion to the antique mythological Europe, who was abducted by Zeus and carried over the water.[8]

Europa regina belongs to the Early Modern allegory of Europa triumphans, as opposed to Europa deplorans.[9]

Related maps

The art of shaping a map in a human form can also be found in a map drawn by Opicino de Canistris, showing the Mediterranean Sea.[3] This map, published in 1340 and thus predating the Putsch map, showed Europe as a man and Northern Africa as a woman.[4]

While in Europa regina maps actual geography is subordinate to the female shape, the opposite approach is seen in a map drawn by Hendrik Kloekhoff and published by Francois Bohn in 1709. In this map, titled "Europa. Volgens de nieuwste Verdeeling" ("Europe, according to the newest classification"), a female is superimposed on a map showing a fairly accurate geography of Europe, and although the map is oriented westward with the Iberian Peninsula forming the head as in the Europa regina imagery, this is resulting in a ducked woman, corresponding with the Europa deplorans rather than the Europa triumphans allegory.[10]

Sources

References

- ^ a b Landwehr & Stockhorst (2004), p. 279

- ^ Werner (2009), p. 243

- ^ a b c d e f g Borgolte (2001), p. 16

- ^ a b Bennholdt-Thomsen (1999), p. 22

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Schmale (2004), p. 244

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Wendehorst & Westphal (2006), p. 63

- ^ a b c d e f g h Werner (2009), p. 244

- ^ a b c d Werner (2009), p. 245

- ^ Werner (2009), pp. 243ff

- ^ Bennholdt-Thomsen (1999), pp. 22-24

Bibliography

- Baridon, Laurent (2011). Un atlas imaginaire, cartes allégoriques et satiriques (in French). Paris: Citadelles & Mazenod. ISBN 978-2-85088-515-0.

- Bennholdt-Thomsen, Anke (1999). Bennholdt-Thomsen, Anke; Guzzoni, Alfredo (eds.). Zur Hermetik des Spätwerks. Analecta Hölderlianas (in German). Vol. 1. Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann. ISBN 3-8260-1629-7.

- Borgolte, Michael (2001). "Perspektiven europäischer Mittelalterhistorie an der Schwelle zum 21. Jahrhundert". In Lusiardi, Ralf; Borgolte (eds.). Das europäische Mittelalter im Spannungsbogen des Vergleichs. Europa im Mittelalter. Abhandlungen und Beiträge zur historischen Komparatistik (in German). Vol. 1. Berlin: Akademie Verlag. pp. 13–28. ISBN 3-05-003663-X.

- Werner, Elke Anna (2009). "Triumphierende Europa - Klagende Europa. Zur visuellen Konstruktion europäischer Selbstbilder in der Frühen Neuzeit". In Ißler, Roland Alexander; Renger, Almut-Barbara (eds.). Europa- Stier und Sternenkranz. Von der Union mit Zeus zum Staatenverbund. Gründungsmythen Europas in Literatur, Musik und Kunst (in German). Vol. 1. Bonn University Press, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. pp. 241–260. ISBN 3-89971-566-7.

- Landwehr, Achim; Stockhorst, Stefanie (2004). Einführung in die europäische Kulturgeschichte. UTB M (in German). Vol. 2562. Paderborn: Schöningh. ISBN 3-8252-2562-3.

- Schmale, Wolfgang (2004). "Europa, Braut der Fürsten. Politische Relevanz des Europamythos im 17. Jahrhundert". In Bussmann, Klaus; Werner, Elke Anna (eds.). Europa im 17. Jahrhundert. Ein politischer Mythos und seine Bilder. Kunstgeschichte (in German). Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag. ISBN 3-515-08274-3.

- Wendehorst, Stephan; Westphal, Siegrid (2006). Lesebuch altes Reich. Bibliothek Altes Reich (in German). Vol. 1. Munich: Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag. ISBN 3-486-57909-6.

External links

Media related to Europa regina at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Europa regina at Wikimedia Commons- Opicino de Canistris' map showing Europe as a man and Africa as a woman, hosted at mittelalter-server.de