Exelon Pavilions

| Exelon Pavilions | |

|---|---|

The Northwest Exelon Pavilion is the Millennium Park Welcome Center and houses the park's office. | |

| General information | |

| Type | Municipal |

| Architectural style | Modern |

| Location | 151 and 201 E. Randolph St. (North) Monroe St. (South) Millennium Park, Chicago, Illinois United States |

| Coordinates | 41°53′2.67″N 87°37′20.54″W / 41.8840750°N 87.6223722°W |

| Current tenants | Millennium Park Welcome Center (NW) Chicago Shop at Millennium Park (NE) Parking garage access (NE, SE, SW) |

| Construction started | January 2004 |

| Completed | July 2004 (South) November 2004 (North) (April 30, 2005 opening) |

| Owner | City of Chicago |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | three (NW), two (NE), one (SW, SE) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Thomas H. Beeby (North) Renzo Piano (South) |

| Engineer | Environmental Systems Design, Inc. (North) |

| Structural engineer | Thorton Tomasetti Engineers (North) |

| Main contractor | Walsh Construction |

The Exelon Pavilions are four buildings that generate electricity from solar energy and provide access to underground parking in Millennium Park in the Loop community area of Chicago in Cook County, Illinois, United States.[1] The Northeast Exelon Pavilion and Northwest Exelon Pavilion (jointly the North Exelon Pavilions) are located on the northern edge of the park along Randolph Street, and flank the Harris Theater. The Southeast Exelon Pavilion and Southwest Exelon Pavilion (jointly the South Exelon Pavilions) are located on the southern edge of the park along Monroe Street, and flank the Lurie Garden. Together the pavilions generate 19,840 kilowatt-hours (71,400 MJ) of electricity annually,[2] worth about $2,350 per year.[3]

The four pavilions, which cost $7 million,[4] were designed in January 2001; construction began in January 2004. The South Pavilions were completed and opened in July 2004, while the North Pavilions were completed in November 2004, with a grand opening on April 30, 2005.[5] In addition to producing energy, three of the four pavilions provide access to the parking garages below the park,[6] while the fourth serves as the park's welcome center and office.[7] Exelon, a company that generates the electricity transmitted by its subsidiary Commonwealth Edison,[4] donated $5.5 million for the pavilions.[2][8][9] Chicago Tribune architecture critic Blair Kamin praised the South Pavilions as "minor modernist jewels", but criticized the North Pavilions as "nearly all black and impenetrable".[4] The North Pavilions have received the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) silver rating from the United States Green Building Council, as well as an award from the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE).[10]

Background

Lying between Lake Michigan to the east and the Loop to the west, Grant Park has been Chicago's front yard since the mid-19th century. Its northwest corner, north of Monroe Street and the Art Institute, east of Michigan Avenue, south of Randolph Street, and west of Columbus Drive, had been Illinois Central rail yards and parking lots until 1997, when it was made available for development by the city as Millennium Park.[11] As of 2009, Millennium Park trailed only Navy Pier as a Chicago tourist attraction.[12]

In 1836, a year before Chicago was incorporated,[13] the Board of Canal Commissioners held public auctions for the city's first lots. Citizens with the foresight to keep the lakefront as public open space convinced the commissioners to designate the land east of Michigan Avenue between Randolph Street and Park Row (11th Street) "Public Ground—A Common to Remain Forever Open, Clear and Free of Any Buildings, or Other Obstruction, whatever."[14] Grant Park has been "forever open, clear and free" since, protected by legislation that has been affirmed by four previous Illinois Supreme Court rulings.[15][16][17] In 1839, United States Secretary of War Joel Roberts Poinsett decommissioned the Fort Dearborn reserve and declared the land between Randolph Street and Madison Street east of Michigan Avenue "Public Ground forever to remain vacant of buildings".[13]

Aaron Montgomery Ward, who is known both as the inventor of mail order and the protector of Grant Park, twice sued the city of Chicago to force it to remove buildings and structures from Grant Park, and to keep it from building new ones.[18][19] In 1890, arguing that Michigan Avenue property owners held easements on the park land, Ward commenced legal actions to keep the park free of new buildings. In 1900, the Illinois Supreme Court concluded that all landfill east of Michigan Avenue was subject to dedications and easements.[20] In 1909, when he sought to prevent the construction of the Field Museum of Natural History in the center of the park, the courts affirmed his arguments and the museum was built elsewhere.[21][22][23]

As a result, the city has what are termed the Montgomery Ward height restrictions on buildings and structures in Grant Park; structures over 40 feet (12 m) tall are not allowed in the park, with the exception of bandshells.[24] However, within Millennium Park, the 50-foot (15 m) Crown Fountain and the 139-foot (42 m) Jay Pritzker Pavilion were exempt from the height restrictions, because they were classified as works of art and not buildings or structures. Shorter structures do not run afoul of the height restrictions. The Harris Theater, which lies between the North Pavilions, was built mostly underground to avoid the restrictions.[25][26] The Northwest Pavilion, tallest of the four, is three stories high; the Northeast Pavilion is two stories, and the South Pavilions are each one story.[5]

Design and construction

The pavilions are named for Exelon, a Chicago-based company that generates the electricity transmitted by its subsidiary Commonwealth Edison (ComEd).[4] The city of Chicago has collaborated with Exelon and ComEd on a variety of environmental projects, including the installation of solar power in buildings, support for sustainable design and renewable energy, and furthering educational and social awareness of green architecture in the city.[10] The pavilions cost $7 million,[4] $5.5 million of which was donated by Exelon and ComEd.[2]

The lead designer for the North Pavilions was Thomas H. Beeby of Hammond Beeby Rupert Ainge Architects.[5] Beeby's designs for the North Pavilions are "in harmony with the Harris Theater",[27] for which he was the architect as well. The North Pavilions are along Randolph Street on either side of the theater, which is Millennium Park's indoor performing-arts venue.[5]

The South Pavilions were designed by architect Renzo Piano of Renzo Piano Building Workshop.[5] Piano designed the Art Institute of Chicago's Modern Wing, which is across Monroe Street from the South Pavilions and opened in 2009. The facades of the South Pavilions are limestone and glass in order to complement the Modern Wing, even though it was not completed until several years after the pavilions were finished.[2] Piano also designed the Nichols Bridgeway, which connects Millennium Park and the Art Institute, and is next to the Southwest Pavilion.[28]

The design process for the Exelon Pavilions began in September 2001, with construction starting in January 2004. The general contractor for all four pavilions was Walsh Construction. The South Pavilions were completed in July 2004 and opened when Millennium Park celebrated its grand opening on July 16, 2004. The North Pavilions were not finished in July 2004, but were completed in November of that year. All four Exelon Pavilions were officially opened to the public on April 30, 2005.[4][5]

Structures

The North Pavilions were designed as minimalist black cubes,[7] and together are capable of producing 16,000 kilowatt-hours (58,000 MJ) of electricity annually.[2] The outermost layer of the exterior of each pavilion is a curtain wall made of recycled aluminum. These walls contain specially designed "mono-crystalline photovoltaic modules and insulated glass".[29] Convection from radiant solar heat gain causes air to cycle within air cavities covered by the photovoltaic modules. A "highly heat-reflective thermoplastic membrane" is used to waterproof each roof, and helps mitigate the urban heat island effect.[29]

The photovoltaic modules generate electricity to power much of the pavilions' lighting.[29] The North Pavilions are the first Chicago buildings to use building integrated photovoltaic cells, which are a solar energy system incorporated into the building's structural elements.[10] Millennium Park's planners claimed that the pavilions had the first electricity-generating curtain walls in the Midwest.[4]

Northwest Pavilion

The Northwest Pavilion, located at 151 E. Randolph Street,[30] houses the Millennium Park Welcome Center and an Exelon energy display.[7] It contains the Millennium Park offices, and public restrooms.[2] The three-story Northwest Pavilion is the largest of the four pavilions, with 6,100 square feet (570 m2),[5] and is the only pavilion that does not provide access to the parking garage below.[7] The Northwest Pavilion has 460 photovoltaic modules to harness solar energy, houses recycling facilities, and its "interior finishes and construction materials are derived from renewable resources".[2]

The Millennium Park Welcome Center in the Northwest Pavilion offers guides to the park and wheelchairs. It houses exhibitions on parks and energy, and has interactive displays on how the pavilions' solar panels function and on renewable energy. There are exhibits with interactive web-based touch screens that depict the city's use of solar energy, and a dynamic multi-screen video presentation on electricity generation and usage. The building's atrium includes a sculpture by Chicago-based artists Patrick McGee and Adelheid Mers with three backlit 9-foot (2.7 m) two-way mirrors. The sculpture, titled Heliosphere, Biosphere, Technosphere, is "designed to interpret the links between the Earth's atmosphere, the solar system and scientific applications".[2] It is the only permanent work of art by Chicago artists within the park.[31]

Northeast Pavilion

The Northeast Pavilion houses a pedestrian entrance to the Millennium Park parking garage,[2] and provides access to the Harris Theater's rooftop terrace.[10][30] It is at 201 E. Randolph Street, east of the theater and west of the McDonald's Cycle Center. The pavilion's second floor has the Chicago Shop, which offers a self-guided Millennium Park audio tour for rental and sells official Millennium Park and Chicago souvenirs.[32] The two-story Northeast Pavilion is the second-largest, with 4,100 square feet (380 m2) of surface area,[5] and also has 460 photovoltaic modules to generate electricity from sunlight.[2]

South Pavilions

The south pavilions are east and west of the Lurie Garden along Monroe Street, and their glass walls allow views of the garden.[4] Both of the South Pavilions provide access to the parking garage below the park. The 550-square-foot (51 m2) Southwest Pavilion is the smallest of the four pavilions,[5] and has the least number of photovoltaic modules with 16 on its roof.[2] It is west of the garden and east of the Nichols Bridgeway. The Southeast Pavilion is east of the garden, has the second smallest area at 750 square feet (70 m2),[5] and has 24 rooftop photovoltaic modules. Together these two pavilions are capable of producing 3,840 kilowatt-hours (13,800 MJ) of electricity annually.[2]

Reception and recognition

Pulitzer Prize-winning Chicago Tribune architecture critic Blair Kamin praised the decision to have architects design the pavilions as an "inspired stroke", speculating that if their designs had been left to contractors, visitors to Millennium Park could have instead seen unimpressive "blunt utilitarian huts".[4] Kamin was pleased with Piano's South Pavilions, describing them as "minor modernist jewels, almost house-like".[4] He lauded the way their limestone walls complement the transparent glass by way of contrast, and noted that they anticipated Piano's then-forthcoming addition to the Art Institute of Chicago Building. Kamin gave the South Pavilions a rating of three stars out of a possible four, or "very good".[4]

Kamin was less pleased with Beeby's North Pavilions, which he described as "nearly all black and impenetrable" and compared to Darth Vader's helmet.[4] He acknowledged the pavilions' innovative technology, and their "urban design function" as wings for the Harris Theater, which Kamin felt "allows the theater to better stand up to the Frank Gehry-designed Pritzker Pavilion to its south".[4] Because they were not finished when he wrote his review in July 2004, Kamin did not give the North Pavilions an overall star rating; he did express the hope that they would have a more pleasant appearance once completed.[4]

The pavilions have been recognized for their innovative use of renewable energy and green design. In 2005, the North Pavilions received the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) silver rating from the United States Green Building Council.[10][33] They received a Technology Award Honorable Mention in the category of "Alternative and/or Renewable Energy Use – New Construction" from the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE).[10][34] The United States Department of Energy has recognized all the pavilions as part of its Million Solar Roofs Initiative. In 2005 Chicago ranked fourth among U.S. cities in solar installations;[2] the completion of the Exelon Pavilions took the city to a total of 1 MW of installed photovoltaic systems.[35] The pavilions together generate 19,840 kilowatt-hours (71,400 MJ) of electricity annually,[2] worth $2,353 per year at 2010 average Illinois electricity prices.[3] According to the City of Chicago, this is enough energy to power the equivalent of 14 Energy Star-rated efficient houses in Chicago.[7]

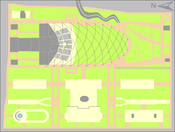

Image map

- Northwest Exelon Pavilion 41°53′2.67″N 87°37′20.54″W / 41.8840750°N 87.6223722°W

- Northeast Exelon Pavilion 41°53′2.72″N 87°37′16.90″W / 41.8840889°N 87.6213611°W

- Southwest Exelon Pavilion 41°52′51.70″N 87°37′20.10″W / 41.8810278°N 87.6222500°W

- Southeast Exelon Pavilion 41°52′51.62″N 87°37′17.02″W / 41.8810056°N 87.6213944°W

Notes

- ^ "North Exelon Pavilions: Chicago, IL". www.hpbmagazine.org. Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "The Millennium Park Welcome Center Opens in the Northwest Exelon Pavilion" (Press release). Brownsey, Anne. Exelon Corporation. April 30, 2005. Archived from the original on November 11, 2006. Retrieved June 7, 2008.

- ^ a b "Average Retail Price of Electricity to Ultimate Customers by End-Use Sector, by State". Energy Information Administration, United States Department of Energy. November 15, 2010. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Kamin, Blair (July 18, 2004). "Exelon Pavilions". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved June 24, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Art & Architecture: Exelon Pavilions Facts and Figures". City of Chicago. Archived from the original on July 24, 2008. Retrieved June 7, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Exelon Pavilions at Millennium Park - Randolph St". www.illinoissolarschools.org. Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e "Art & Architecture: Exelon Pavilions: Millennium Park Welcome Center and Garage Entrances". City of Chicago. Archived from the original on May 26, 2008. Retrieved June 7, 2008.

- ^ Herrmann, Andrew (July 15, 2004). "Sun-Times Insight". Chicago Sun-Times. p. 16.

- ^ "Dawn of the Millennium". Chicago Tribune. July 16, 2004. Retrieved July 20, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f Ryan, Karen (December 15, 2005). "Millennium Park's North Exelon Pavilions Receive a "LEED Silver" Rating" (Press release). City of Chicago, Department of Environment. Retrieved August 31, 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Gilfoyle, Timothy J. (August 6, 2006). "Millennium Park". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved June 24, 2008.

- ^ "Crain's List: Chicago's Largest Tourist Attractions (Sightseeing): Ranked by 2009 attendance". Crain's Chicago Business. Crain Communications Inc. March 22, 2010. p. 21.

- ^ a b Macaluso, pp. 12–13

- ^ Gilfoyle, pp. 3–4

- ^ Spielman, Fran (June 12, 2008). "Mayor gets what he wants – Council OKs move 33–16 despite opposition". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved November 16, 2009.

- ^ "The taking of Grant Park". Chicago Tribune. June 8, 2008. Retrieved July 29, 2008.

- ^ Spielman, Fran; Art Golab (May 16, 2008). "13–2 vote for museum – Decision on Grant Park sets up Council battle". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved July 29, 2008.

- ^ Grinnell, Max (2005). "Grant Park". The Electronic Encyclopedia of Chicago. Chicago Historical Society. Retrieved July 28, 2008.

- ^ Macaluso, pp. 23–25

- ^ City of Chicago v. A. Montgomery Ward, 169 Ill. 392 (1897).

- ^ Gilfoyle, p. 16

- ^ E. R. Bliss v. A. Montgomery Ward, 104 198 Ill. (1902).; A. Montgomery Ward v. Field Museum of Natural History, 241 Ill. 496 (1909).; and South Park Commissioners v. Ward & Co., 248 Ill. 299 (1911).

- ^ Ward chose not to challenge the Art Institute of Chicago building in the park. For an overview of the legal cases involving Grant Park and structures within it, please see: Ward, Richard F. (November 18, 2008). "Illinois Supreme Court Decisions". NewEastside.org. Retrieved September 17, 2010..

- ^ Flanagan, p. 141.

- ^ Gilfoyle, p. 181

- ^ "In a fight over Grant Park, Chicago's mayor faces a small revolt" (subscription required). The Economist. The Economist Newspaper Limited. October 4, 2007. Retrieved July 31, 2008.

- ^ "Millennium Park Inc.: Exelon Pavilions Series". Chicago Public Library. 2008. Retrieved July 9, 2008.

- ^ "The Modern Wing" (PDF). The Art Institute of Chicago. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2008. Retrieved August 31, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c "Hammond Beeby Rupert Ainge: Exelon Pavilions". Chicago Architecture Foundation. Archived from the original on August 12, 2007. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

- ^ a b "Exelon Pavilions at Millennium Park – Randolph St". The Chicago Solar Partnership. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

- ^ Flanagan, p. 139.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions". City of Chicago. Archived from the original on June 22, 2007. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Millennium Park brochure, "Exelon Pavilions,"" (PDF). City of Chicago. p. 39. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 12, 2010. Retrieved September 3, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Jalayerian, Mehdi; Steven Eich (September 2006). "Blending Architecture And Renewable Energy" (PDF). ASHRAE Journal. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 11, 2010. Retrieved September 26, 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Exelon Energy Solutions: Supply and Demand". Pew Center on Global Climate Change. Archived from the original on July 6, 2010. Retrieved July 20, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

References

- Flanagan, Regina M. (2008). "The Millennium Park Effect: A Tale of Two Cities". In Cartiere, Cameron; Shelley Willis (eds.). The Practice of Public Art. New York, New York: Routledge Research in Cultural and Media Studies. ISBN 978-0-415-96292-6.

- Gilfoyle, Timothy J. (2006). Millennium Park: Creating a Chicago Landmark. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-29349-3.

- Macaluso, Tony; Julia S. Bachrach; Neal Samors (2009). Sounds of Chicago's Lakefront: A Celebration Of The Grant Park Music Festival. Chicago's Book Press. ISBN 978-0-9797892-6-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)

External links