Filippo Brunelleschi

Filippo Brunelleschi | |

|---|---|

Presumed depiction in Resurrection of the Son of Theophilus, Masaccio | |

| Born | Filippo di ser Brunellesco di Lippo Lapi[1] 1377 Florence, Italy |

| Died | April 15, 1446 (aged 68–69) 'Florence |

| Known for | Architecture, sculpture, mechanical engineering |

| Notable work | Dome of Santa Maria del Fiore |

| Movement | Early Renaissance |

Filippo Brunelleschi (Italian: [fiˈlippo brunelˈleski]; 1377 – April 15, 1446) was an Italian designer and a key figure in architecture, recognised to be the first modern engineer, planner and sole construction supervisor.[4] He was one of the founding fathers of the Renaissance. He is generally well known for developing a technique for linear perspective in art and for building the dome of the Florence Cathedral. Heavily depending on mirrors and geometry, to "reinforce Christian spiritual reality", his formulation of linear perspective governed pictorial depiction of space until the late 19th century.[5][6] It also had the most profound – and quite unanticipated – influence on the rise of modern science.[6] His accomplishments also include other architectural works, sculpture, mathematics, engineering, and ship design. His principal surviving works are to be found in Florence, Italy. Unfortunately, his two original linear perspective panels have been lost.

Brunelleschi was born in Florence, Italy.[7] Little is known about his early life, the only sources being Antonio Manetti and Giorgio Vasari.[8] According to these sources, Filippo's father was Brunellesco di Lippo, a notary, and his mother was Giuliana Spini. Filippo was the middle of their three children. The young Filippo was given a literary and mathematical education intended to enable him to follow in the footsteps of his father, a civil servant. Being artistically inclined, however, Filippo enrolled in the Arte della Seta, the silk merchants' Guild, which also included goldsmiths, metalworkers, and bronze workers. He became a master goldsmith in 1398. It was thus not a coincidence that his first important building commission, the Ospedale degli Innocenti, came from the guild to which he belonged.[9]

In 1401, Brunelleschi entered a competition to design a new set of bronze doors for the Florence Baptistery. Seven competitors each produced a gilded bronze panel, depicting the Sacrifice of Isaac. Brunelleschi's entry, which, with that of Lorenzo Ghiberti, is one of only two to have survived, made reference to the Greco-Roman Boy with Thorn. Brunelleschi's panel consists of several pieces bolted to the back plate.[10]

As an architect

Brunelleschi is considered a seminal figure of the Renaissance. Little biographical information about Brunelleschi's life exists to explain his transition from goldsmith to architect, nor of his training in the gothic or medieval manner or transition to the new classicism in architecture and urbanism. By 1400 there emerged an interest in humanitas, which contrasted with the formalism of the medieval period, but initially this new interest in Roman antiquity was restricted to a few scholars, writers and philosophers; it did not at first influence the visual arts. Apparently it was in this period (1402–1404) that Brunelleschi and his friend Donatello visited Rome to study the ancient Roman ruins. Donatello, like Brunelleschi, had received his training in a goldsmith's workshop, and had then worked in Ghiberti's studio. Although in previous decades the writers and philosophers had discussed the glories of Ancient Rome, it seems that until Brunelleschi and Donatello made their journey, no one had studied the physical fabric of these ruins in any great detail. They also gained inspiration from ancient Roman authors, especially Vitruvius, whose De Architectura provided an intellectual framework for the standing structures still visible.

Commissions

Brunelleschi's first architectural commission was the Ospedale degli Innocenti (1419–ca.1445), or Foundling Hospital. Its long loggia would have been a rare sight in the tight and curving streets of Florence, not to mention its impressive arches, each about 8 meters high. The building was dignified and sober; there were no displays of fine marble or decorative inlays.[11] It was also the first building in Florence to make clear reference—in its columns and capitals—to classical antiquity.

Soon other commissions came, such as the Ridolfi Chapel in the church of San Jacopo sopr'Arno, now lost, and the Barbadori Chapel in Santa Felicita, also modified since its building. For both, Brunelleschi devised elements already used in the Ospedale degli Innocenti, and which would also be used in the Pazzi Chapel and the Sagrestia Vecchia. At the same time he was using such smaller works as a sort of feasibility study for his most famous work, the dome of the Cathedral of Florence.

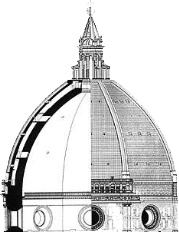

Florence Cathedral

Santa Maria del Fiore was the new cathedral of the city, and by 1418 the dome had yet to be defined. When the building was designed in the previous century, no one had any idea how such a dome was to be built, given that it was to be even larger than the Pantheon's dome in Rome and that no dome of that size had been built since antiquity. Because buttresses were forbidden by the city fathers, and because it was impossible to obtain rafters for scaffolding long and strong enough (and in sufficient quantity) for the task, it was unclear how a dome of that size could be constructed without it collapsing under its own weight. Also, the stresses of compression were not clearly understood, and the mortars used in the period would set only after several days, keeping the strain on the scaffolding for a very long time.[12]

In 1418, the Arte della Lana, the wool merchants' guild, held a competition to solve the problem. The two main competitors were Ghiberti and Brunelleschi, with Brunelleschi winning and receiving the commission. The competition consisted of the great architects attempting to stand an egg upright on a piece of marble. None could do it but Brunelleschi, who, according to Vasari:[13] "... giving one end a blow on the flat piece of marble, made it stand upright ...The architects protested that they could have done the same; but Filippo answered, laughing, that they could have made the dome, if they had seen his design." (This solution was also attributed to Columbus; see Egg of Columbus.)

The dome, the lantern (built 1446–ca.1461) and the exedra (built 1439–1445) would occupy most of Brunelleschi's life.[14] Brunelleschi's success can be attributed, in no small degree, to his technical and mathematical genius.[15] Brunelleschi used more than four million bricks in the construction of the dome. He invented a new hoisting machine for raising the masonry needed for the dome, a task no doubt inspired by republication of Vitruvius' De Architectura, which describes Roman machines used in the 1st century AD to build large structures such as the Pantheon and the Baths of Diocletian, structures still standing which he would have seen for himself. He also issued one of the first patents for the hoist in an attempt to prevent the theft of his ideas. Brunelleschi was granted the first modern patent for his invention of a river transport vessel.[16]

Brunelleschi kept his workers up in the building during their breaks and brought food and diluted wine, similar to that given to pregnant women at the time, up to them. He felt the trip up and down the hundreds of stairs would exhaust them and reduce their productivity.[17]

Other work

Brunelleschi's interests extended to mathematics and engineering and the study of ancient monuments. He invented hydraulic machinery and elaborate clockwork, none of which survives.

Brunelleschi also designed fortifications used by Florence in its military struggles against Pisa and Siena. In 1424, he was working in Lastra a Signa, a village protecting the route to Pisa, and in 1431 in the south of Italy on the walls of the village of Staggia. These walls are still preserved, but whether they are specifically by Brunelleschi is uncertain.

He also was active briefly in the world of shipmaking, when, in 1427, he built an enormous ship named Il Badalone to transport marble to Florence from Pisa up the Arno River. The ship sank on its maiden voyage, along with a sizable chunk of Brunelleschi's personal fortune.[18] Besides his accomplishments in architecture, Brunelleschi is also credited with inventing one-point linear perspective which revolutionized painting and paved the way for naturalistic styles to develop as the Renaissance digressed from the stylized figures of medieval art. In addition, he was somewhat involved in urban planning: he strategically positioned several of his buildings in relation to the nearby squares and streets for "maximum visibility". For example, demolitions in front of San Lorenzo were approved in 1433 in order to create a piazza facing the church. At Santo Spirito, he suggested that the façade be turned either towards the Arno so travelers would see it, or to the north, to face a large, prospective piazza.

Discovery of linear perspective

Brunelleschi is famous for two panel paintings illustrating geometric optical linear perspective made in the early 15th century. His biographer, Antonio Manetti, described this famous experiment in which Brunelleschi painted two panels: the first being the Florentine Baptistery as viewed frontally from the western portal of the unfinished cathedral, the other one is the Palazzo Vecchio seen obliquely from its northwest corner. These were not, however, the first paintings with accurate linear perspective, which may be attributed to Ambrogio Lorenzetti (Annunciation, 1344).

The first Baptistery panel was constructed with a hole drilled through the centric vanishing point. Curiously, Brunelleschi intended that it only be observed by the viewer facing the Baptistery, looking through the hole in the panel, from the unpainted backside. As a mirror was moved into and out of view, the observer saw the striking similarity between the actual view of the Baptistery, and the reflected view of the painted Baptistery image. Brunelleschi wanted his new perspective "realism" to be tested not by comparing the painted image to the actual Baptistery but to its reflection in a mirror according to the Euclidean laws of geometric optics. This feat showed artists vividly how they might paint their images, not merely as flat two-dimensional shapes, but looking more like three-dimensional structures, just as mirrors reflect them. Unfortunately, both panels have since been lost.[19]

Around this time linear perspective, as a novel artistic tool, spread not only in Italy but throughout Western Europe. It quickly became, and remains, standard studio practice.

Theatrical machinery

Brunelleschi also designed machinery for use in churches during theatrical religious performances that re-enacted Biblical miracle stories. Contrivances were created by which characters and angels were made to fly through the air in the midst of spectacular explosions of light and fireworks. These events took place during state and ecclesiastical visits. It is not known for certain how many of these Brunelleschi designed, but at least one, for the church of San Felice, is confirmed in the records.[9]

Death

Brunelleschi's body lies in the crypt of the Cathedral of Florence. As explained by Antonio Manetti, who knew Brunelleschi and who wrote his biography, Brunelleschi "was granted such honors as to be buried in the Basilica di Santa Maria del Fiore, and with a marble bust, which was said to be carved from life, and placed there in perpetual memory with such a splendid epitaph."[20] Inside the cathedral entrance is this epitaph: "Both the magnificent dome of this famous church and many other devices invented by Filippo the architect, bear witness to his superb skill. Therefore, in tribute to his exceptional talents, a grateful country that will always remember him buries him here in the soil below."

Principal works

The principal buildings and works designed by Brunelleschi or which included his involvement:

- Dome of the Cathedral of Florence, (1419–1436)

- Ospedale degli Innocenti, (1419–ca.1445)

- Basilica di San Lorenzo di Firenze, (1419–1480s)

- Meeting Hall of the Palazzo di Parte Guelfa, (1420s–1445)

- Sagrestia Vecchia, or Old Sacristy of S. Lorenzo, (1421–1440)

- Santa Maria degli Angeli: unfinished, (begun 1434)

- The lantern of the Florence Cathedral, (1436–ca.1450)

- The exedrae of the Florence Cathedral, (1439–1445)

- Santo Spirito di Firenze, (1441–1481)

- Pazzi Chapel, (1441–1460s)

See also

References

- ^ Walker, Paul Robert (2003). The Feud That Sparked the Renaissance: How Brunelleschi and Ghiberti Changed the Art World. HarperCollins. p. 5. ISBN 0-380-97787-7.

- ^ "The Duomo of Florence | Tripleman". tripleman.com. Retrieved March 25, 2010.

- ^ "brunelleschi's dome – Brunelleschi's Dome". Brunelleschisdome.com. Archived from the original on April 16, 2010. Retrieved March 25, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Bodart, Diane (2008). Renaissance & Mannerism. New York: Sterling. ISBN 978-1402759222.

- ^ "Filippo Brunelleschi". Encyclopedia.com.

- ^ a b Edgerton, Samuel. "Brunelleschi's mirror, Alberti's window, and Galileo's 'perspective tube'".

- ^ http://www.biography.com/people/filippo-brunelleschi-9229632

- ^ For an English version of Vasari's description of the life and work of Brunelleschi, see: http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/basis/vasari/vasari5.htm

- ^ a b Battisti, Eugenio (1981). Filippo Brunelleschi. New York: Rizzoli. ISBN 0-8478-5015-3.

- ^ Walker, Paul Robert (2002). The Feud that Sparked the Renaissance: How Brunelleschi and Ghiberti Changed the Art World. New York: William Morrow. ISBN 0-380-97787-7.

- ^ Klotz, Heinrich (1990). Filippo Brunelleschi: the Early Works and the Medieval Tradition. Translated by Hugh Keith. London: Academy Editions. ISBN 0-85670-986-7.

- ^ King, Ross (2001). Brunelleschi's Dome: The Story of the great Cathedral of Florence. New York: Penguin. ISBN 0-8027-1366-1.

- ^ From Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, published 1500. Quoted from 'Italian Renaissance', Martin Roberts for Longman, 1992

- ^ Saalman, Howard (1980). Filippo Brunelleschi: The Cupola of Santa Maria del Fiore. London: A. Zwemmer. ISBN 0-302-02784-X.

- ^ Prager, Frank (1970). Brunelleschi: Studies of his Technology and Inventions. Cambridge: The MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-16031-5.

- ^ The origins of the industrial property right. See: http://www.european-patent-office.org/wbt/pi-tour/tour.php Step 3.

- ^ "Medici: Godfathers of the Renaissance". February 18, 2004. PBS. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

{{cite episode}}: Missing or empty|series=(help) - ^ Brunelleschi's Monster Patent: Il Badalone

- ^ For proposed reconstructions of Brunelleschi's demonstration, see Edgerton, Samuel Y. (2009). The Mirror, the Window & the Telescope: How Renaissance Linear Perspective Changed Our Vision of the Universe. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-4758-7. And István Orosz, http://www.gallery-diabolus.com/gallery/artist.php?image=1612&id=utisz&page=214

- ^ Manetti, Antonio (1970). The Life of Brunelleschi. English translation of the Italian text by Catherine Enggass. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-271-00075-9.

Further reading

- Argan, Giulio Carlo; Robb, Nesca A (1946). "The Architecture of Brunelleschi and the Origins of Perspective Theory in the Fifteenth Century". J. Warburg and Courtauld Institutes. 9: 96–121. doi:10.2307/750311. JSTOR 750311.

- Fanelli, Giovanni (2004). Brunelleschi's Cupola: Past and Present of an Architectural Masterpiece. Florence: Mandragora.

- Heydenreich, Ludwig H. (1996). Architecture in Italy, 1400–1500. New Haven/London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-06467-4.

- Hyman, Isabelle (1974). Brunelleschi in perspective. Prentice-Hall.

- Kemp, Martin (1978). "Science, Non-science and Nonsense: The Interpretation of Brunelleschi's Perspective". Art History. 1 (2): 134–161.

- Prager, F. D. (1950). "Brunelleschi's Inventions and the 'Renewal of Roman Masonry Work'". Osiris. 9: 457–554. doi:10.1086/368537.

- Millon, Henry A.; Lampugnani, Vittorio Magnago, eds. (1994). The Renaissance from Brunelleschi to Michelangelo: the Representation of Architecture. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Trachtenberg, Marvin (1988). What Brunelleschi Saw: Monument and Site at the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence. New York.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - King, Ross (2000). Brunelleschi's Dome: How a Renaissance Genius Reinvented Architecture. New York: Walker. ISBN 0-8027-1366-1.

- Devémy, Jean-François (2013). Sur les traces de Filippo Brunelleschi, l'invention de la coupole de Santa Maria del Fiore à Florence. Suresnes: Les Editions du Net. ISBN 978-2-312-01329-9. (in line presentation)

- Saalman, Howard (1993). Filippo Brunelleschi: The Buildings. Penn State Press.

- Vereycken, Karel, "The Secrets of the Florentine Dome", Schiller Institute, 2013. (Translation from the French, "Les secrets du dôme de Florence", la revue Fusion, n° 96, Mai, Juin 2003)

- "The Great Cathedral Mystery", PBS Nova TV documentary, February 12, 2014

External links

Media related to Filippo Brunelleschi at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Filippo Brunelleschi at Wikimedia Commons- Free audio guide of Brunelleschi's Dome

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Filippo Brunelleschi", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- Italian Renaissance architects

- Italian civil engineers

- Renaissance engineers

- 1377 births

- 1446 deaths

- Architects of cathedrals

- Architects from Florence

- People of the Republic of Florence

- Italian Roman Catholics

- History of patent law

- 14th century in the Republic of Florence

- 15th century in the Republic of Florence

- 14th-century engineers

- 15th-century engineers

- 14th-century Italian architects

- 15th-century Italian architects