Fire of Moscow (1812)

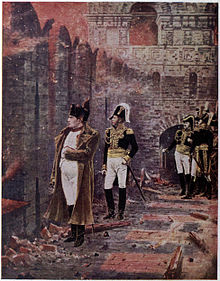

Fire of Moscow by Alexander Smirnov, 1813 | |

| Date | 14–18 September 1812 |

|---|---|

| Location | Moscow, Russian Empire |

| Outcome | Russian evacuation

|

During the French occupation of Moscow, a fire persisted from 14 to 18 September 1812 and all but destroyed the city. The Russian troops and most of the remaining civilians had abandoned the city on 14 September 1812 just ahead of French Emperor Napoleon's troops entering the city after the Battle of Borodino.[2][3][4] The Moscow military governor, Count Fyodor Rostopchin, has often been considered responsible for organising the destruction of the sacred former capital to weaken the French army in the scorched city even more.[5][6][7]

Background

[edit]After continuing Barclay's "delaying operation"[8] as part of his attrition warfare against Napoleon, Kutuzov used Rostopchin to burn most of Moscow's resources as part of a scorched earth strategy, guerilla warfare by the Cossacks against French supplies and total war by the peasants against French foraging.[9] This kind of war without major battles weakened the French army at its most vulnerable point: military logistics.[10] On 19 October 1812 the French army, lacking provisions and being warned by the first snow, abandoned the city voluntarily.[11]

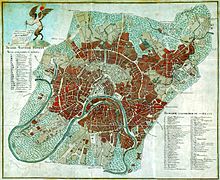

Regarding the state of Moscow itself, the city was mostly deserted, at least in comparison to its normal levels of population: At the beginning of 1812 Moscow had around 270,184 inhabitants according to a contemporary police survey;[12] of these, somewhere between 6,200 and 10,000 civilians chose to remain in the city after the arrival of the French, in addition to between 10,000 and 15,000 sick or wounded Russian soldiers.[13]

Causes

[edit]

Search had been made for the fire-engines since the previous day, but some of them had been taken away and the rest put out of action...The Poles reported that they had already caught some incendiaries and shot them, ...they had extracted the information that orders had been given by the Governor of the city and the police that the whole city should be burnt during the night.[14][15]

Before leaving Moscow, Count Rostopchin supposedly gave orders to the head of police (and released convicts) to have the Kremlin and major public buildings (including churches and monasteries) set on fire.[citation needed] During the following days, the fires spread. According to Germaine de Staël, who left the city a few weeks before Napoleon arrived, and afterward corresponded with Kutuzov, it was Rostopchin who ordered his own mansions to be set on fire, so no Frenchmen should lodge in it.[16] The French actress Louise Fusil, who was living in Moscow, wrote that the fire started at Petrovka Street and offers more details in her memoires. Today, the majority of historians blame the initial fires on the Russian strategy of scorched earth.[17][6]

Furthermore, a Moscow police officer was captured trying to set the Kremlin on fire where Napoleon was staying at the time. Brought before Napoleon, the officer admitted he and others had been ordered to set the city on fire, after which he was bayonetted by guardsmen on the spot on the orders of a furious Napoleon.[18]

The sight of the fire deeply disturbed Napoleon who was horrified and intimidated at the Russian resolution to destroy their most sacred and beloved city before surrendering it. According to him most churches, monasteries and palaces survived as they were made out of stone. A witness records him as remaining transfixed watching the fire from the Kremlin while saying: "What a terrible sight! And they did this themselves! So many palaces! What an incredible solution! What kind of people! These are Scythians!"[19]

The catastrophe started as many small fires, which promptly grew out of control and formed a massive blaze from the northeast, according to Larrey.[20] The fires spread quickly since most buildings in Moscow were made of wood, except in the German Quarter. Although Moscow had had a fire brigade, their equipment had previously either been removed or destroyed on Rostopchin's orders. The flames spread into the Kremlin's arsenal, and was put out by French Guardsmen. The burning of Moscow is reported to have been visible up to 215 km, or 133 miles, away.[21]

Tolstoy, in his book War and Peace, suggests that the fire was not deliberately set, either by the Russians or the French, but was the natural result of placing a deserted and mostly wooden city in the hands of invading troops. Before the invasion, fires would have started nearly every day even with the owners present and a fully functioning fire department, and the soldiers would start additional fires for their own needs, from smoking their pipes, cooking their food twice a day, and burning enemies' possessions in the streets. Some of those fires would inevitably get out of control, and without an efficient firefighting action, these individual building fires can spread to become neighborhood fires, and ultimately a citywide conflagration.[22][23]

Timeline of events

[edit]

- 7 September – Battle of Borodino;

- 8 September – Russian army began retreating east from Borodino.[24] They camped outside Mozhaysk.[25][26] When the village of Mozhaysk was captured by the French on the 9th, the Grande Armée rested for two days to recover.[27]

- 9 September Napoleon asked Berthier to send reinforcements from Minsk to Smolensk and from Smolensk to Moscow.

- 10 September – The main quarter of the Russian army was situated at Bolshiye Vyazyomy.[28] Kutuzov settled in a manor on the high road to Moscow. The owner was Dmitry Golitsyn, who entered military service again. Russian sources suggest Mikhail Kutuzov wrote a number of orders and letters to Rostopchin about saving the city or the army.[29][30]

- 11 September – Tsar Alexander signed a document that Kutuzov was promoted General Field Marshall, the highest military rank. Napoleon, still in Mozhaysk, wrote Marshal Victor to hurry to Moscow.[31]

- 12 September – the main forces of Kutuzov departed from the village, now Golitsyno and camped near Odintsovo, 20 km to the west, followed by Mortier and Joachim Murat's vanguard.[32] Eugene de Beauharnais attacked Savvino-Storozhevsky Monastery. Napoleon Bonaparte, who suffered from a cold and lost his voice, spent the night at Vyazyomy Manor (on the same sofa in the library) within 24 hours.[33]

- 13 September – Napoleon leaves the manor house and heads east.[34] Napoleon and Józef Poniatowski also camped near Odintsovo and invited Murat for dinner. Russian army set camp at Fili; Russian vanguard lodged nearby in Dorogomilovo. On Sunday afternoon the Russian military council at Fili discussed the risks and agreed to abandon Moscow without fighting. Leo Tolstoy wrote Rostopchin was invited also and explained the difficult decision in quite a few remarkable chapters. The troops started at once. "They were passing through Moscow from two o'clock at night, till two in the afternoon and bore away with them the wounded and the last of the inhabitants who were leaving."[35] The civilian flight from Moscow was organized by Miloradovich while Kutuzov kept a low profile during the retreat using side streets.[36]

- 14 September – The Russian army crossed the Moskva river near Sparrow Hills and marched through Moscow into a southeast bound road to Ryazan, followed by masses of civilians.[37] Napoleon arrived at Poklonnaya Hill. After a ceasefire Murat's corps was the first to ride through the city, taking the Kremlin in the afternoon, leaving the inhabitants enough time to depart. First fires broke out in the evening.[3]

- 15 September – More wind and massive fires. Napoleon arrives at Kremlin.[38] It was seven o'clock in the evening when suddenly a shot rang out from the Kaluga Gate. The enemy blew up a powder magazine, which must have been the signal agreed upon; several rockets shoot up at once, and half an hour later a fire appeared in several blocks of the city.[39] The wind changed direction and reached hurricane strength. Six or seven thousand little shops caught fire again.[17][40]

- 16 September – By four in the morning the firestorm threatens Kremlin.[41] Watching the fire from Kremlin Hill, Napoleon relocated to the suburban and empty Petrovsky Palace (located on the road to Saint Petersburg) in the afternoon.[38][42] According to sergeant Adrien Bourgogne: "Orders had been given to shoot everyone found setting fire to houses. This order was executed at once. A little open space next to the Place du Gouvernement was called by us the Place des Pendus, as here a number of incendiaries were shot and hung on the trees."[43]

- 18 September – Fire destroys three-quarters of the city and settling down; when it begins to rain, Napoleon returns to the Kremlin.[44]

- 19 September – Murat lost sight of Kutuzov who changed direction and turned west to Podolsk and Tarutino where he would be more protected by the surrounding hills and the Nara river.[45][46][47]

- 20 September – Napoleon sends a message to propose peace to the Tsar who is based in Saint Petersburg.

- 21 September – The fires are finally subsided.

- 23 September – Order given for the two battalions of the 33rd Regiment to break away. As they were daily bothered by numerous pulks of Cossacks' Napoleon ordered to clean the area and forage with the assistance of the Dutch flying squadron. On 25 September, in collaboration with German infantrymen and French dragoons, it had to sweep the area around Malye Vyaziomy.[48]

- 24 September – Dinners were held at the Kremlin, with promotions and ribbons, and a theatre was set up.

- 26 September – After losing sight of the Russian army, Murat finally detects them near Podolsk.

- 27 September – A ball was held. Everyone put on their newly acquired clothes and drank rum punch. First snowfall of the season; the French army is suffering from famine and the cold.[49][50]

- 28 September – A large supply of foodstuffs was seized at Malye Vyaziomy by Johan Frederik Wilhelm Veeren and loaded onto 26 wagons. They were pursued by Cossacks who managed to take 15 wagons.[51][52]

- 3 October – Kutuzov and his entire staff arrived at Tarutino. He wanted to go even further in order to control three-pronged roads from Obninsk, so that Napoleon could not turn south or southwest.

Kutuzov avoided frontal battles involving large masses of troops. This tactic was sharply criticized by Chief of Staff Bennigsen and others, but also by the Autocrat and Emperor Alexander.[55] Barclay de Tolly interrupted his service for five months and settled in Nizhny Novgorod.[56][57] Each side avoided the other and seemed no longer to wish to get into a fight.Kutuzov's food supplies and reinforcements were mostly coming up through Kaluga from the fertile and populous southern provinces, his new deployment gave him every opportunity to feed his men and horses and rebuild their strength. He refused to attack; he was happy for Napoleon to stay in Moscow for as long as possible, avoiding complicated movements and maneuvers.[53][54]

- 4 October – A plan to march the French army to Saint Petersburg was given up; absolute lack of forage, limited cavalry and artillery as horses died on the spot. Murat and his cavalry arrived at Winkovo and settled near a lake,[49][58] watching the Russian army, but he was forced to withdraw into a ravine. A network of Cossacks and armed peasants were killing all isolated men.[59][60][61][62][63]

- 5 October – On order of Napoleon, the French ambassador Jacques Lauriston leaves Moscow to meet Kutuzov at his headquarters near Tarutino. Kutuzov agreed to meet, despite the orders of the Tsar.[64] Rostopchin owned an estate near Tarutino, Russia. Robert Wilson was with him, when Rostopchin set fire to his estate.[65][66]

- 7 October – Although the weather was fine and the temperature mild, not a single (French) courier from Moscow reached Vilnius, due to a lack of horses.[67]

- 8 October – Murat personally asked Miloradovich to let his cavalry go foraging.[68][69]

- 15 October – Napoleon ordered evacuation of the 12,000 sick and wounded to Smolensk.[70][71]

- 17 October – French columns again passed the Nara river and proceeded to their respective destinations.

- 18 October – At dawn during breakfast, Murat's camp in a forest was surprised by an attack by forces led by Bennigsen, known as Battle of Winkovo. Bennigsen was supported by Kutuzov from his headquarters at distance. Murat loses 12 guns, 3,000 men, and 20 of his baggage carts. Bennigsen asked Kutuzov to provide troops for the pursuit. However, the General Field Marshal refused.[72]

- 19 October – After 36 days, the French army (around 108,000) leaves Moscow at seven in the morning. Before he left, Mortier was to blow up the Kremlin, but the marshal did not have enough time to complete this task and only managed a small explosion. Napoleon made camp in the village of Troitsk, Moscow on the Desna River. Napoleon's goal was to get around Kutuzov, but on the 24th he was stopped at Maloyaroslavets on his way to Medyn and forced to go north on the 26th.

Extent of the disaster

[edit]

...In 1812, there had been approximately 4,000 stone structures and 8,000 wooden houses in Moscow. Of these, there remained after the fires only about 200 of the stone buildings and some 500 wooden houses along with about half of the 1,600 (?) churches, although nearly every church was damaged to some extent...the large number of churches that escaped total destruction by the flames is probably explained by the fact that altar implements and other paraphernalia were made of precious metals, which immediately attracted the attention of the looters. Indeed, Napoleon had a systematic sweep made for the church silver, which ended up in his war chest, the mobile treasury.[3]

The treatment of these Russians left behind, civilians or soldiers, by the French was mixed: According to a Russian source, they destroyed monasteries and blew up architectural monuments. Moscow churches were deliberately turned into stables and latrines. Priests who did not give up church shrines were murdered savagely, nuns were raped, and stoves were fired using ancient icons. On the other hand, Napoleon personally made sure that enough food was delivered to Moscow to feed all the Russians left behind who were fed regardless of sex or age.[73][74]

Still, the remaining buildings had enough space for the French army. As General Marcellin Marbot reasoned:

"It is often claimed that the fire of Moscow... was the principal cause of the failure of the 1812 campaign. This assertion seems to me to be contestable. To begin with, the destruction of Moscow was not so complete that there did not remain enough houses, palaces, churches, and barracks to accommodate the entire army [for a whole month]."[75]

Reconstruction of the city

[edit]

The process of rebuilding after the fire under military governor Alexander Tormasov (1814–1819) and Dmitry Golitsyn (1820–ca 1840) was gradual, lasting well over a decade.[76][77][78]

In culture

[edit]- Leo Tolstoy describes the occupation and fire in his novel War and Peace (Book XI).

Tolstoy portrays the decision-making after Borodino in the first four chapters of book 11 of War and Peace. This opens with an essay on the difficulty, or maybe even the impossibility, or determining cause and effect in history. He attacks, in particular, the 'great man' theory of history, which says that events can be explained by "the actions of some one man – a king or a commander": that Kutuzov, for example, gave the order for the army to abandon Moscow to the French, and therefore they did so.[79]

- Louise Fusil, a French actress, who was living in Russia for six years, witnessed the fire and described in her memoir the retreat.

- Kutuzov, Russian movie (1943) with English subtitles, describes also the Fire of Moscow (1812).

- The fire was adapted into 1965–67 Soviet film War and Peace; the film crew planned out the scenes for 10 months and shot the fires with six ground cameras while also filming from helicopters.[80]

- The fire is depicted in the 1955 film Napoléon, as well as in the 2023 film Napoleon.

Notes

[edit]- ^ (in Russian) Kataev, I.M. (1912) "The Fire of Moscow in 1812 "(Moscow, 1911)

- ^ Haythornthwaite 2012, pp. 40–72, The Battle of Borodino.

- ^ a b c Riehn 1990, p. 285.

- ^ Mikaberidze 2014, pp. 96–111, Chapter 6: The Great Conflagration.

- ^ Mikaberidze 2014, pp. 68–95, Chapter 5: 'And Moscow, Mighty City, Blaze!'.

- ^ a b Mikaberidze 2014, pp. 145–165, Chapter 8: 'By Accident or Malice?' Who Burned Moscow.

- ^ Zemtsov, Vladimir Nikolaevich (2012). "French Jesuit Abbot A. Surugue and the 1812 Fire of Moscow Historic Myth". Izvestiya Uralskogo Federalnogo Universiteta – Seriya 2 – Gumanitarnye Nauki. 14 (2). Yekaterinburg, Russia: Ural Federal University: 118–133. ISSN 2227-2283.

- ^ US DOD 2021.

- ^ Chandler 2009, pp. 749–766, 68. War Plans and Preparations (Part Thirteen. The Road to Moscow).

- ^ Chandler 2009, pp. 813–822, 71. Precarious Position (Part Fourteen. Retreat).

- ^ Riehn 1990, p. 321.

- ^ Martin, Alexander M. (2002). "The Response of the Population of Moscow to the Napoleonic Occupation of 1812". In Lohr, Eric; Poe, Marshall (eds.). The Military and Society in Russia: 1450–1917. History of warfare. Vol. XIV. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill. pp. 469–490. ISBN 978-9004122734.

- ^ Mikaberidze, Alexander (2014). Masséna, Victor-André; Lentz, Thierry; de Bruchard, Marie; Boulant, Antoine; Delage, Irène (eds.). "Napoleon's Lost Legions. The Grande Armée Prisoners of War in Russia". Napoleonica. La Revue. Spécial prisonniers de guerre. 21 (3). Paris, Ile de France, France: Fondation Napoléon: 35–44. doi:10.3917/napo.153.0035. ISSN 2100-0123 – via Cairn.INFO.

- ^ Caulaincourt 1935, p. 118, VI. The Fire.

- ^ Vionnet 2013, pp. 73–97, 12. The Great Fire.

- ^ Staël-Holstein 1821, p. 352.

- ^ a b Austin 2012, pp. 26–28, Chapter 1: "Fire! Fire!".

- ^ Ludwig 1927, p. 408, Book Four: The Sea.

- ^ Ludwig 1927, p. 430, Book Four: The Sea.

- ^ "Surgical memoirs of the campaigns of Russia, Germany, and France", pp. 43–45

- ^ Luhn, Alec (14 September 2012). Richardson, Paul E.; Widmer, Scott; Shine, Eileen; Matte, Caroline (eds.). "Moscow's Last Great Fire". Russian Life. Montpelier, Vermont, United States of America: StoryWorkz. Archived from the original on 18 June 2020. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- ^ War and Peace, Vol. 3, Book XI, chapter 26

- ^ Russia: A Short History by Abraham Ascher

- ^ Riehn 1990, p. 260.

- ^ "The Burning of Moscow". 31 August 2015.

- ^ Haythornthwaite 2012, p. 74, The End of the Campaign.

- ^ Wilson 2013, p. 159, Uncandid Despatch of Kutusow.

- ^ Wolzogen und Neuhaus, Justus Philipp Adolf Wilhelm Ludwig (1851). Wigand, O. (ed.). Memoiren des Königlich Preussischen Generals der Infanterie Ludwig Freiherrn von Wolzogen [Memoirs of the Royal Prussian General of the Infantry Ludwig Freiherrn von Wolzogen] (in German). Leipzig, Germany: Wigand. LCCN 16012211. OCLC 5034988.

- ^ https://www.nivasposad.ru/school/homepages/all_kurs/konkurs2013/web-pages/web/filippov_andreji/html/bolshie_vyazemi.html Archived 2021-05-13 at the Wayback Machine Russian: Большие Вязёмы

- ^ Lieven 2009, pp. 210–211, 5. The Retreat.

- ^ de Segúr, Philip (23 April 1825). "Segur's History of Napoleon's Expedition". The Literary Gazette, and Journal of Belles Lettres, Arts, Sciences, Etc. IX (431). London: Whiting & Branston: 262–263. Retrieved 26 September 2021 – via Google Books.

- ^ Adam, Albrecht (2005) [1990]. North, Jonathan (ed.). Napoleon's Army in Russia: The Illustrated Memoirs of Albrecht Adam, 1812. Pen & Sword Military. Translated by North, Jonathan (2nd ed.). Barnsley, England: Pen & Sword Books Limited. ISBN 978-1-84415-161-5.

- ^ https://architecturebest.com/usadba-bolshie-vjazemy/ Russian: Усадьба Большие Вяземы

- ^ Austin 2012, pp. 69–70, Chapter 4: A Desconsolate Advance Guard.

- ^ War and Peace, Vol. 3, Book XI, chapter 19

- ^ War and Peace, Vol. 3, Book XI, chapter 19

- ^ Riehn 1990, p. 290.

- ^ a b Riehn 1990, p. 286.

- ^ Dedem van de Gelder, Anton Boudewijn Gijsbert van (1900). van Dedem Lecky, Elisabeth (ed.). Un général hollandais sous le premier empire: Mémoires du général Bon de Dedem de Gelder, 1774–1825 [A Dutch general under the First Empire: Memoirs of general Bon de Dedem de Gelder, 1774–1825] (in French). Paris: Libraire Plon, Nourrit et Cie, Imprimeurs-Éditeurs. p. 250. LCCN 01017275. OCLC 1007804088 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Austin 2012, p. 223, Chapter 13: "That's Enough, Gentlemen. I Shall Decide".

- ^ "Moscow's Last Great Fire".

- ^ Zamoyski 2004, p. 300, 14. Hollow Triumph.

- ^ Bourgogne 1899, p. 31, Chapter II. The Fire at Moscow.

- ^ Zamoyski 2004, p. 304, 14. Hollow Triumph.

- ^ Wilson 2013, p. 170, Position of the Russian Army on the road to Kalouga.

- ^ Wilson 2013, p. 175, Manoeuvres of hostile armies.

- ^ Wilson 2013, p. 177, Manoeuvres of the hostile armies.

- ^ 1812: Napoleon in Moscow by Paul Britten Austin

- ^ a b Austin 2012, p. 73, Chapter 4: A Desconsolate Advance Guard.

- ^ Austin 2012, p. 85, Chapter 5: Settling in for the Winter.

- ^ A Dutch officer of the 33rd Light Infantry Regiment, Russia 1812

- ^ F.H.A. Sabron (1910) Geschiedenis van het 33e regiment Lichte Infanterie (het Oud-Hollandsche 3e regiment Jagers) onder Keizer Napoleon I, p. 64

- ^ Lieven 2009, p. 214, 5. The Retreat.

- ^ Lieven 2009, p. 252, 6. Borodino and the Fall of Moscow.

- ^ Wilson 2013, p. 203, Letter of reproof from Alexander to Kutusow.

- ^ Lieven 2009, p. 253, 6. Borodino and the Fall of Moscow.

- ^ Lieven 2009, p. 296, 7. The Home Front in 1812.

- ^ Austin 2012, p. 79, Chapter 4: A Desconsolate Advance Guard.

- ^ Austin 2012, p. 93, Chapter 5: Settling in for the Winter.

- ^ Austin 2012, p. 102, Chapter 6: Marauding Parties.

- ^ Austin 2012, p. 104, Chapter 7: Lovely Autumn Weather.

- ^ Austin 2012, p. 152, Chapter 8: A Lethal Truce.

- ^ Austin 2012, p. 174, Chapter 10: Battle at Waterloo.

- ^ Wilson 2013, p. 181, Contemplated treachery of Kutusow.

- ^ Austin 2012, pp. 141–142, Chapter 8: A Lethal Truce.

- ^ Wilson 2013, pp. 178–180, Patriotism of Rostopchin.

- ^ Austin 2012, pp. 107–108, Chapter 7: Lovely Autumn Weather.

- ^ Austin 2012, p. 123, Chapter 8: A Lethal Truce.

- ^ Austin 2012, p. 114, Chapter 7: Lovely Autumn Weather.

- ^ Austin 2012, p. 202, Chapter 12: "Where Our Conquest of the World Ended".

- ^ Wilson 2013, p. 209, Combat of Czenicznia and brilliant conduct of Murat.

- ^ Zemtsov, Vladimir Nikolaevich (15 August 2015). Glantz, David (ed.). "The Fate of the Russian Wounded Abandoned in Moscow in 1812". The Journal of Slavic Military Studies. 28 (3). Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States of America: Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies/Taylor & Francis or Routledge: 502–523. doi:10.1080/13518046.2015.1061824. ISSN 1351-8046. LCCN 93641610. OCLC 56751630. S2CID 142674272.

- ^ Zakharov, Arthur (2004). Napoleon v Rossii glazami russkikh [Napoleon in Russia through the eyes of the Russians] (in Russian) (1st ed.). Moscow, Russia.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Marbot 1913, p. 602, Vol. II, Chapter LXXIV.

- ^ Luhn 2012.

- ^ Alekseevna, Molokova Tatyana (1 June 2012). Telichenko, Valery Ivanovich; Korol, Elena Anatolievna; Dyadicheva, Anna A.; Bernikova, Tat'yana V. (eds.). "Восстановление Москвы после пожара 1812 г.: новый облик города" [Reconstruction of Moscow after the 1812 fire of Moscow: New look of the city]. Vestnik MGSU. Архитектура и градостроительство. Реконструкция и реставрация (in Russian). 7 (6). Moscow, Russia: Moscow State University of Civil Engineering/ASB Publishing House, LLC.: 17–22. doi:10.22227/1997-0935.2012.6.17-22. ISSN 1997-0935.

- ^ Shvidkovsky, Dmitry; Yesoulov, Georgy (28 August 2017). The classical models brought by European architects to the development of the St. Petersburg and the reconstruction of Mosco after the Great Fire of 1812. 4th International Multidisciplinary Scientific Conference on Social Sciences and Arts SGEM 2017. International Multidisciplinary Scientific Conference on Social Sciences & Arts Sgem. Vol. 17. Sofia, Bulgaria: SWS International Scientific Conferences on Social Sciences, Arts & Humanities. pp. 59–66. doi:10.5593/sgemsocial2017/62/S22.007 (inactive 2024-11-02). ISBN 978-619-7408-24-9. ISSN 2367-5659. Archived from the original on 2022-02-09. Retrieved 2022-02-09.

{{cite conference}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ "Russian literature – in War and Peace, why do all the generals and Kutuzov consider it "impossible" to defend Moscow?".

- ^ Taylor 2019.

Bibliography

[edit]- Austin, Paul Britten (2012). 1812: Napoleon in Moscow (2nd ed.). Barnsley, England: Frontline Books. ISBN 978-1-4738-1139-3. Retrieved 26 September 2021 – via Google Books.

- Bourgogne, Adrien Jean Baptiste François (1899). Cottin, Paul (ed.). Memoirs of Sergeant Bourgogne, 1812–1813 (2nd ed.). New York: Doubleday & McClure Company. LCCN 99001646. Retrieved 26 September 2021 – via Internet Archive.

- Caulaincourt, Armand-August-Louis de (1935). Libaire, George; Morrow, William (eds.). With Napoleon in Russia: The memoirs of General de Caulaincourt, Duke of Vicenza. New York: William Morrow and Company, Inc. Retrieved 26 September 2021 – via Internet Archive.

- Haythornthwaite, Philip; et al. (Illustrations and graphics by Peter Dennis) (2012). Cowper, Marcus (ed.). Borodino 1812: Napoleon's great gamble. Campaign. Vol. 246. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84908-697-4. Retrieved 26 September 2021 – via Google Books.

- Lieven, Dominic (2009). Dohle, Markus; Wright, Deborah; Weldon, Tom; Prior, Joanna (eds.). Russia Against Napoleon: The Battle for Europe, 1807 to 1814. London: Allen Lane (Penguin Books). ISBN 978-0-14-194744-0. OCLC 419644822 – via Google Books.

- Marbot, Jean-Baptiste Antoine Marcelin (1913) [1891]. The memoirs of General Baron de Marbot, late lieutenant-general in the French army. Vol. I. Translated by Butler, Arthur John (5th ed.). London: Longmans, Green, and Co. Retrieved 26 September 2021 – via Internet Archive.

- Ludwig, Emil (1927). Allen, George (ed.). Napoleon. Translated by Eden, Paul; Cedar, Paul (7th ed.). London: Unwin Brothers Ltd. Retrieved 26 September 2021 – via Internet Archive.

- Riehn, Richard K. (1990). 1812: Napoleon's Russian campaign. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-052731-7. LCCN 89028432. OCLC 20563997. Retrieved 26 September 2021 – via Internet Archive.

- Taylor, Ella (27 June 2019). Mulvaney, John; Turell, Saul J.; Becker, William J. (eds.). "War and Peace: Saint Petersburg Fiddles, Moscow Burns". The Criterion Collection. Essays. New York: The Criterion Collection, Inc. (Janus Films). Archived from the original on 3 July 2019. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- Staël-Holstein, Anne Louise Germain de (1821). de Staël-Holstein, Augustus (ed.). Ten Years' Exile; or Memoirs of that Interesting Period of the Life of the Baroness de Staël-Holstein. London: Treuttel and Würtz/Hewlett & Brimmer, Printers. OCLC 5938603. Retrieved 26 September 2021 – via Internet Archive.

- Vionnet, Louis Joseph (2013). With Napoleon's Guard in Russia: The Memoirs of Major Vionnet, 1812. Casemate Publishers. ISBN 978-1-78340-898-6 – via Google Books.

- Zamoyski, Adam (2004) [1980]. Moscow 1812: Napoleon's Fatal March (2nd ed.). New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-107558-2. LCCN 2004047575. OCLC 55067008. Retrieved 26 September 2021 – via Internet Archive.

- US DOD (2021). "delaying operation".

Further reading

[edit]- Chambray, George de, Histoire de l'expédition de Russie [1] Chambray, George de, Histoire de l'expédition de Russie access-date=7 March 2021

- Chandler, David G.; et al. (Graphics and illustrations by Shelia Waters, design by Abe Lerner) (2009) [1966]. Lerner, Abe (ed.). The Campaigns of Napoleon: The mind and method of history's greatest soldier. Vol. I (4th ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4391-3103-9. OCLC 893136895. Retrieved 26 September 2021 – via Google Books.

- Clausewitz, Carl von, "Der Feldzug 1812 in Russland und die Befreiungskriege von 1813–15", 1906, [2]

- Franceschi, Michel; Weider, Ben (2008). The wars against Napoleon: Debunking the myth of the Napoleonic Wars. Translated by House, Jonathan M. (2nd ed.). New York: Savas Beatie. ISBN 978-1-61121-029-3. Retrieved 26 September 2021 – via Google Books.

- V. Fillipov, "Dynamics of ethnic and confessional identity of Moscow population", citing Russian edition of: На пути к переписи / Под редакцией Валерия Тишкова – М.: "Авиаиздат", 2003 с. 277–313 "Как менялся этнический состав москвичей". Demoscope.ru. Retrieved 2013-09-28.

- Холодковский В.М., Наполеон ли поджёг Москву?, «Вопросы истории», 1966, No. 4.

- Kataev, I.M. "Fire of Moscow", citing Russian edition of "Отечественная война и русское общество", в 7тт, т.4, М, издание т-ва И.Д.Сытина, 1911 "╚Нревеярбеммюъ Бнимю Х Псяяйне Наыеярбн╩. Рнл Iv. Лняйбю Опх Тпюмжсгюу. Онфюп Лняйбш". Museum.ru. Retrieved 2013-09-28.

- Martin, Alexander, Enlightened Metropolis: Constructing Imperial Moscow, 1762–1855, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2013.

- Martin, Alexander, From the Holy Roman Empire to the Land of the Tsars: One Family's Odyssey, 1768–1870, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2022.

- Mikaberidze, Alexander (2014). The Burning of Moscow: Napoleon's Trial By Fire 1812. Pen & Sword Military. Barnsley, England: Pen & Sword Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1-78159-352-3 – via Google Books.

- Olivier, Daria, The Burning of Moscow 1812, London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd. 1966 (JSTOR – The Scholarly Journal Archive review)

- Rosenstrauch, J.A., "Historische Ereignisse in Moskau im Jahre 1812 zur Zeit der Anwesenheit des Feindes in dieser Stadt" (German-language memoir text), in: И.А. Розенштраух, Исторические происшествия в Москве 1812 года во время присутствия в сем городе неприятеля, М., Новое Литературное Обозрение, 2015, pp. 169–220 – ISBN 978-5-4448-0270-0.

- Ruchinskaya, Tatiana (1994). "The Scottish architectural traditions in the plan for the reconstruction of Moscow after the fire of 1812: A rare account of the influence of Scottish architect William Hastie on town planning in Moscow". Building Research & Information. 22 (4): 228–233. doi:10.1080/09613219408727386.

- Schmidt, Albert J. (21 March 1981). Koenker, Diane P. (ed.). "The Restoration of Moscow after 1812". Slavic Review. 40 (1). Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies (ASEEES)/University of Pittsburgh/Cambridge University Press: 37–48. doi:10.2307/2496426. ISSN 0037-6779. JSTOR 2496426. LCCN 47006565. OCLC 818900629. S2CID 163600450. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- Sytin, P.V. "History of Moscow Streets", citing original Russia edition: Сытин, П.В., "Из истории московских улиц", М, 1948.* Полосин И.И., Кутузов и пожар Москвы 1812 г., «Исторические записки», 1950, т. 34.

- Tarle, Yevgeny, "Napoleon's Invasion of Russia", citing Russian edition of: Тарле, Е.В., "Нашествие Наполеона на Россию", гл.VI "Пожар Москвы" at "Е.Б. Рюпке ╚Мюьеярбхе Мюонкенмю Мю Пняяхч╩". Museum.ru. Retrieved 2013-09-28.

- Тартаковский А.Г., Обманутый Герострат. Ростопчин и пожар Москвы, «Родина», 1992, No. 6–7.

- Wilson, Robert Thomas (2013) [1860]. Randolph, Herbert (ed.). Narrative of events during the Invasion of Russia by Napoleon Bonaparte, and the Retreat of the French Army, 1812. Cambridge Library Collection (3rd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-05400-3. Retrieved 26 September 2021 – via Google Books.