Food coloring

Food coloring, or color additive, is any dye, pigment or substance that imparts color when it is added to food or drink. They come in many forms consisting of liquids, powders, gels, and pastes. Food coloring is used both in commercial food production and in domestic cooking. Due to its safety and general availability, food coloring is also used in a variety of non-food applications including cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, home craft projects, and medical devices.[2]

Purpose of food coloring

People associate certain colors with certain flavors, and the color of food can influence the perceived flavor in anything from candy to wine.[3] Sometimes the aim is to simulate a color that is perceived by the consumer as natural, such as adding red coloring to glacé cherries (which would otherwise be beige), but sometimes it is for effect, like the green ketchup that Heinz launched in 1999. Color additives are used in foods for many reasons including:[4][5]

- Offset color loss due to exposure to light, air, temperature extremes, moisture and storage conditions

- Correct natural variations in color

- Enhance colors that occur naturally

- Provide color to colorless and "fun" foods

- Make food more attractive and appetizing, and informative

- Allow consumers to identify products on sight, like candy flavors or medicine dosages

- Food colorants, synthetic

-

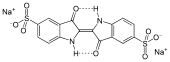

Indigo Carmine, which is blue.

-

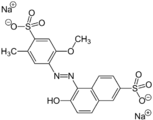

Allura Red AC, which is red.

-

Quinoline Yellow WS, which is yellow.

- Food colorants, natural

-

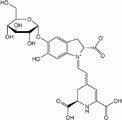

Betanin, a magenta dye, mainly produced from beets.

-

Anthocyanin, a red to blue dye depending on functional groups and pH.

-

beta-Carotene, a yellow to orange colorant.

Regulation

Past use and regulation history

The addition of colorants to foods is thought to have occurred in Egyptian cities as early as 1500 BC, when candy makers added natural extracts and wine to improve the products' appearance.[6] During the Middle Ages, the economy in the European countries was based on agriculture, and the peasants were accustomed to producing their own food locally or trading within the village communities. Under feudalism, aesthetic aspects were not considered, at least not by the vast majority of the generally very poor population.[7] This situation changed with urbanization at the beginning of the Modern Age, when trade emerged—especially the import of precious spices and colors. One of the very first food laws, created in Augsburg, Germany, in 1531, concerned spices or colorants and required saffron counterfeiters to be burned.[8]

With the onset of the industrial revolution, people became dependent on foods produced by others.[7] These new urban dwellers demanded food at low cost. Analytical chemistry was still primitive and regulations few. The adulteration of foods flourished.[7] Heavy metal and other inorganic element-containing compounds turned out to be cheap and suitable to "restore" the color of watered-down milk and other foodstuffs, some more lurid examples being:[9]

- Red lead (Pb3O4) and vermillion (HgS) were routinely used to color cheese and confectionery.

- Copper arsenite (CuHAsO3) was used to recolor used tea leaves for resale. It also caused two deaths when used to color a dessert in 1860.

Sellers at the time offered more than 80 artificial coloring agents, some invented for dyeing textiles, not foods.[9]

...Thus, with potted meat, fish and sauces taken at breakfast he would consume more or less Armenian bole, red lead, or even bisulphuret of mercury. At dinner with his curry or cayenne he would run the chance of a second dose of lead or mercury; with pickles, bottled fruit and vegetables he would be nearly sure to have copper administrated to him; and while he partook of bon-bons at dessert, there was no telling of the number of poisonous pigments he might consume. Again his tea if mixed or green, he would certainly not escape without the administration of a little Prussian blue...[10]

Many color additives had never been tested for toxicity or other adverse effects. Historical records show that injuries, even deaths, resulted from tainted colorants. In 1851, about 200 people were poisoned in England, 17 of them fatally, directly as a result of eating adulterated lozenges.[7] In 1856, mauveine, the first synthetic color, was developed by Sir William Henry Perkin and by the turn of the century, unmonitored color additives had spread through Europe and the United States in all sorts of popular foods, including ketchup, mustard, jellies, and wine.[11]

Concerns over food safety led to numerous regulations throughout the world,. German food regulations released in 1882 stipulated the exclusion of dangerous minerals such as arsenic, copper, chromium, lead, mercury and zinc, which were frequently used as ingredients in colorants.[12] In contrast to today, these first laws followed the principle of a negative listing (substances not allowed for use); they were already driven by the main principles of today's food regulations all over the world, since all of these regulations follow the same goal: the protection of consumers from toxic substances and from fraud.[7] In the United States, the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 reduced the permitted list of synthetic colors from 700 down to seven.[13] Even with updated food laws, adulteration continued for many years and this, together with more recent adverse press comments on food colors and health, has continued to contribute to consumer concern about color addition to foodstuffs.

In the 20th century, the improvement of chemical analysis and the development of trials to identify the toxic features of substances added to foods led to the replacement of the negative lists by lists of substances allowed to be used for the production and the improvement of foods. This principle is called a positive listing, and almost all recent legislations are based on it.[7] Positive listing implies that substances meant for human consumption have been tested for their safety, and that they have to meet specified purity criteria prior to their approval by the corresponding authorities. In 1962, the first EU directive (62/2645/EEC) approved 36 colorants, of which 20 were naturally derived and 16 were synthetic.[14] This directive did not list which food products the colorants could or could not be used in. At that time, each member state could designate where certain colors could and could not be used. In Germany, for example, quinoline yellow was allowed in puddings and desserts, but tartrazine was not. The reverse was true in France.[8] This was updated in 1989 with 89/107/EEC, which concerned food additives authorized for use in foodstuffs.[15]

Current regulation

While naturally derived colors are not required to be certified by a number of regulatory bodies throughout the world (including the U.S. FDA), they still need to be approved for use in that country. The FDA lists "color additives exempt from certification" for food in subpart A of the Code of Federal Regulations - Title 21 Part 73. However, this list contains substances which may have synthetic origins, such as nature identical beta-carotene. FDA's permitted colors are classified as subject to certification or exempt from certification, both of which are subject to rigorous safety standards prior to their approval and listing for use in foods.

- Certified colors are synthetically produced and are used widely because they impart an intense, uniform color, are less expensive, and blend more easily to create a variety of hues. There are nine certified color additives approved for use in the United States. Certified food colors generally do not add undesirable flavors to foods.

- Colors that are exempt from certification include pigments derived from natural sources such as vegetables, minerals or animals. Nature derived color additives are typically more expensive than certified colors and may add unintended flavors to foods. Examples of exempt colors include annatto, beet extract, caramel, beta-carotene, turmeric and grape skin extract.

Food colorings are tested for safety by various bodies around the world and sometimes different bodies have different views on food color safety. In the United States, FD&C numbers (which indicate that the FDA has approved the colorant for use in foods, drugs and cosmetics) are given to approved synthetic food dyes that do not exist in nature, while in the European Union, E numbers are used for all additives, both synthetic and natural, that are approved in food applications. The food colors are known by E numbers that begin with a 1, such as E100 (turmeric) or E161b (lutein).[16] The safety of food colors and other food additives in the EU is evaluated by the European Food Safety Authority. Color Directive 94/36/EC, enacted by the European Commission in 1994, outlines permitted natural and artificial colors with their approved applications and limits in different foodstuffs.[8] This is binding to all member countries of the EU. Any changes have to be implemented into their national laws within a given time frame. In non-EU member states, food additives are regulated by their national authorities, which usually, but not in all cases, try to harmonize with the laws adopted by the EU. Most other countries have their own regulations and list of food colors which can be used in various applications, including maximum daily intake limits.

Global harmonization

Global trade requires harmonization of food regulations on a world-wide basis in order to abolish barriers of trade and to ensure that the economic and nutritional demands of all nations are considered. Since the beginning of the 1960s, JECFA has played an important role in the development of international standards for food additives, not only by its toxicological assessments, which are continuously published by the WHO in a "Technical Report Series", but furthermore by elaborating appropriate purity criteria, which are laid down in the two volumes of the "Compendium of Food Additive Specifications" and their supplements. These specifications are not legally binding but very often serve as a guiding principle, especially in countries where no scientific expert committees have been established.[7]

In order to further regulate the use of these evaluated additives, in 1962 the WHO and FAO created an international commission, the Codex Alimentarius, which is composed of authorities, food industry associations and consumer groups from all over the world. Within the Codex organization, the Codex Committee for Food Additives and Contaminants is responsible for working out recommendations for the application of food additives, the General Standard for Food Additives. In the light of the World Trade Organizations General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), the Codex Standard, although not legally binding, influences food color regulations all over the world.[7]

Artificial coloring

As the 1900s began, a host of synthetic dyes and pigments became available.[5] Originally, these were dubbed `coal-tar' colors because the starting materials were obtained from bituminous coal.[17] Many synthesized dyes were easier and less costly to produce and were superior in coloring properties when compared to naturally derived alternatives of the time.[9]

Also known as "azo-dyes", synthetic colors are generally produced via a two-step chemical synthesis. The first step forms a diazo compound from the reaction of aromatic amines generally formed from nitrosamine and a diazonium compound. The second step couples these diazo compounds with various reactive aromatic hydrocarbons.[18] Due to the π-electrons across the two aromatic sections and the azo-groups, a conjugated system exists that is able to absorb light of specific wavelengths, leading to the color of the compounds (this principle also applies to naturally derived pigments as well).

The attractiveness of the synthetic dyes is that their color, lipophilicity, and other attributes can be engineered by the design of the specific molecule. The color of the dyes can be controlled selecting the number of azo-groups and various substituents. Yellow shades are achieved by using acetoacetanilide and heterocyclic compounds. Red colors result from the reaction between an aniline derivative (diazo) with a naphthol derivate. A blue results from replacing the aniline derivate with a benzidine derivate.[18] The pair indigo and indigo carmine exhibit the same color, but the former is soluble in lipids, and the latter is water soluble because it has been fitted with sulfonate functional groups.

In the United States

Only seven dyes were initially approved under the U.S. Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, but several have been delisted and replacements have been found.[19] Some of the food colorings have the abbreviation "FCF" in their names. This stands for "For Coloring Food" (US)[20] or "For Colouring of Food" (UK).[21]

In the United States, manufacturers must get FDA approval for every batch of certified colors produced. FDA personnel evaluate the color's physical appearance and chemically analyze it. Tests include purity (total color content), moisture, residual salts, unreacted intermediates, colored impurities other than the main color (called subsidiary colors), any other specified impurities, and heavy metals (lead, arsenic, and mercury). The results are reviewed for compliance with the identity and specifications described in the listing regulation for the color additive.[22] If the sample is found to meet these requirements, the FDA issues a certificate for the batch that identifies the color additive. For example, a batch of "tartrazine" becomes "FD&C Yellow No. 5."

Current seven generally permitted

In the US, the following seven artificial colorings are generally permitted in food (the most common in bold) as of 2016[update]. The lakes of these colorings are also permitted except the lake of Red No. 3.[23]

- FD&C Blue No. 1 – Brilliant Blue FCF, E133 (blue shade)

- FD&C Blue No. 2 – Indigotine, E132 (indigo shade)

- FD&C Green No. 3 – Fast Green FCF, E143 (turquoise shade)

- FD&C Red No. 3 – Erythrosine, E127 (pink shade, commonly used in glacé cherries)[24]

- FD&C Red No. 40 – Allura Red AC, E129 (red shade)

- FD&C Yellow No. 5 – Tartrazine, E102 (yellow shade)

- FD&C Yellow No. 6 – Sunset Yellow FCF, E110 (orange shade)

Permitted for limited use in foods

Two dyes are allowed by the FDA for limited applications:

- Citrus Red 2 (orange shade) - allowed only to color orange peels.

- Orange B (red shade) - allowed only for use in hot dog and sausage casings (not produced after 1978, but never delisted)

Delisted and banned in the US

- FD&C Red No. 2 – Amaranth, E123

- FD&C Red No. 4[25][26]

- FD&C Red No. 32 was used to color Florida oranges.[19][25][27]

- FD&C Orange Number 1 was one of the first water-soluble dyes to be commercialized, and one of seven original food dyes allowed under the Pure Food and Drug Act of June 30, 1906.[19][25]

- FD&C Orange No. 2 was used to color Florida oranges.[19]

- FD&C Yellow No. 1, 2, 3, and 4[25]

- FD&C Violet No. 1[25]

Approved in EU

E numbers 102-143 cover the range of artificial colors. For an overview of currently allowed additives see here [1]. Some artificial dyes approved for food use in the EU include:

- E104: Quinoline Yellow

- E122: Carmoisine

- E124: Ponceau 4R

- E131: Patent Blue V

- E142: Green S

Natural food dyes

Carotenoids (E160, E161, E164), chlorophyllin (E140, E141), anthocyanins (E163), and betanin (E162) comprise four main categories of plant pigments grown to color food products.[28] Other colorants or specialized derivatives of these core groups include:

- Annatto (E160b), a reddish-orange dye made from the seed of the achiote

- Caramel coloring (E150a-d), made from caramelized sugar

- Carmine (E120), a red dye derived from the cochineal insect, Dactylopius coccus

- Elderberry juice

- Lycopene (E160d)

- Paprika (E160c)

- Turmeric (E100)

Blue colors are especially rare.[29]

To ensure reproducibility, the colored components of these substances are often provided in highly purified form. For stability and convenience, they can be formulated in suitable carrier materials (solid and liquids). Hexane, acetone, and other solvents break down cell walls in the fruit and vegetables and allow for maximum extraction of the coloring. Traces of these may still remain in the finished colorant, but they do not need to be declared on the product label. These solvents are known as carry-over ingredients.

Dyes and lakes

Color additives are available for use in food as either "dyes" or lake pigments (commonly known as "lakes").

Dyes dissolve in water, but are not soluble in oil. Dyes are manufactured as powders, granules, liquids or other special purpose forms. They can be used in beverages, dry mixes, baked goods, confections, dairy products, pet foods, and a variety of other products. Dyes also have side effects that lakes lack. Consuming large amounts of dyes can color stools.

Lakes are made by combining dyes with salts (usually aluminum salts) to make insoluble compounds. Lakes tint by dispersion. Lakes are not oil-soluble, but are oil-dispersible. Lakes are more stable than dyes and are ideal for coloring products containing fats and oils or items lacking sufficient moisture to dissolve dyes. Typical uses include coated tablets, cake and doughnut mixes, hard candies and chewing gums, lipsticks, soaps, shampoos, talc, etc.

Other uses

Because food dyes are generally safer to use than normal artists' dyes and pigments, some artists have used food coloring as a means of making pictures, especially in forms such as body-painting. Red food dye is often used in theatrical blood.

Most artificial food colorings are a type of acid dye, and can be used to dye protein fibers and nylon with the addition of an acid. They are all washfast and most are also lightfast. They will not permanently bond to plant fibers and other synthetics.[30]

Criticism and health implications

Widespread public belief that artificial food coloring cause hyperactivity in children originated with Benjamin Feingold a pediatric allergist from California, who proposed in 1973 that salicylates, artificial colors, and artificial flavors cause hyperactivity in children;[31] however, there is no evidence to support broad claims that food coloring causes food intolerance and ADHD-like behavior in children.[32]: 452 [33] It is possible that certain food coloring may act as a trigger in those who are genetically predisposed, but the evidence is weak.[34][35]

After concerns were expressed that food colorings may cause ADHD-like behavior in children,[34] the collective evidence do not support this assertion.[36] The US FDA and other food safety authorities to regularly review the scientific literature, and led the UK Food Standards Agency (FSA) to commission a study by researchers at Southampton University of the effect of a mixture of six food dyes (Tartrazine, Allura Red, Ponceau 4R, Quinoline Yellow WS, Sunset Yellow and Carmoisine (dubbed the "Southampton 6")) on children in the general population. These colorants are found in beverages.[34][37] The study found "a possible link between the consumption of these artificial colours and a sodium benzoate preservative and increased hyperactivity" in the children;[34][37] the advisory committee to the FSA that evaluated the study also determined that because of study limitations, the results could not be extrapolated to the general population, and further testing was recommended".[34] The U.S. FDA did not make changes following the publication of the Southampton study, but following a citizen petition filed by the Center for Science in the Public Interest in 2008, requesting the FDA ban several food additives, the FDA reviewed the available evidence, and still made no changes.[34]

The European regulatory community, with an emphasis on the precautionary principle, required labelling and temporarily reduced the acceptable daily intake (ADI) for the food colorings; the UK FSA called for voluntary withdrawal of the colorings by food manufacturers.[34][37] However, in 2009 the EFSA re-evaluated the data at hand and determined that "the available scientific evidence does not substantiate a link between the color additives and behavioral effects" for any of the dyes.[34][38][39][40][41]

See also

References

- ^ Ian P. Freeman, "Margarines and Shortenings" Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 2005, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim doi:10.1002/14356007.a16_145

- ^ CFR Title 21 Part 70: Color Additive Regulations, FDA, retrieved Feb 15, 2012

- ^ Jeannine Delwiche (2003). "The impact of perceptual interactions on perceived flavor" (PDF). Food Quality and Preference. 14 (2): 137–146. doi:10.1016/S0950-3293(03)00041-7.

- ^ "Food Ingredients & Colors". International Food Information Council. June 29, 2010. Retrieved Feb 15, 2012.

- ^ a b Barrows, Julie N.; Lipman, Arthur L.; Bailey, Catherine J. (17 Dec 2009). "Color Additives: FDA's Regulatory Process and Historical Perspectives". FDA (Reprinted from Food Safety Magazine October/November 2003 issue). Retrieved 2 Mar 2012.

Although certifiable color additives have been called coal-tar colors because of their traditional origins, today they are synthesized mainly from raw materials obtained from petroleum.

- ^ Meggos, H. (1995). "Food colours: an international perspective". The Manufacturing Confectioner. pp. 59–65.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h Arlt, Ulrike (29 Apr 2011). "The Legislation of Food Colours in Europe". The Natural Food Colours Association. Retrieved 18 Feb 2014.

- ^ a b c Cook, Jim. "Colorants Compliance". The World of Food Ingredients (Sept 2013). Arnhem, The Netherlands: CNS Media BV: 41–43. ISSN 1566-6611.

- ^ a b c Downham, Alison; Collins, Paul (2000). "Colouring our foods in the last and next millennium" (PDF). International Journal of Food Science and Technology. 35. Blackwell Science Ltd: 5–22. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2621.2000.00373.x. Retrieved 18 Feb 2014.

- ^ Hassel, A.H. (1960). Amos, Arthur James (ed.). Pure Food and Pure Food Legislation. Butterworths, London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Walford, J. (1980). "Historical Development of Food Colouration". Developments in Food Colours. 1. London: Applied Science Publishers: 1–25.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Hastings, Robert W. (January–March 1898). Hamilton, John B. (ed.). "Human Food Laws". Journal of the American Medical Association. 30 (1–13). Chicago: American Medical Association: 419–421. doi:10.1001/jama.1898.72440600019002e. Retrieved 17 Feb 2014.

- ^ Meadows, Michelle (2006). "A Century of Ensuring Safe Foods and Cosmetics". FDA Consumer magazine (January–February). FDA. Retrieved 21 Feb 2014.

- ^ EEC: Council Directive on the approximation of the rules of the Member States concerning the colouring matters authorized for use in foodstuffs intended for human consumption OJ 115, 11.11.1962, p. 2645–2654 (DE, FR, IT, NL) English special edition: Series I Volume 1959-1962 p. 279–290

- ^ Council Directive 89/107/EEC of 21 December 1988 on the approximation of the laws of the Member States concerning food additives authorized for use in foodstuffs intended for human consumption OJ L 40, 11.2.1989, p. 27–33 (ES, DA, DE, EL, EN, FR, IT, NL, PT)

- ^ "Current EU approved additives and their E Numbers". Food Standards Agency. 26 Nov 2010. Retrieved 20 Feb 2012.

- ^ Hancock, Mary (1997). "Potential for Colourants from Plant Sources in England & Wales" (PDF). UK Central Science Laboratory. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

The use of natural dyes in the UK and the rest of the Western economies has been replaced commercially by synthetic dyes, based mainly on aniline and using petroleum or coal tar as the raw stock.

- ^ a b König, J. (2015), "Food colour additives of synthetic origin", in Scotter, Michael J. (ed.), Colour Additives for Foods and Beverages, Elsevier, pp. 35–60, doi:10.1016/B978-1-78242-011-8.00002-7, ISBN 978-1-78242-011-8

- ^ a b c d "News of Food; U.S. May Outlaw Dyes Used to Tint Oranges and Other Foods". New York Times. January 19, 1954.

The use of artificial colors to make foods more attractive to the eye may be sharply curtailed by action of the United States Food and Drug Administration. Three of the most extensively used coal tar dyes are being considered for removal from the Government's list of colors certified as safe for internal and external use and consumption.

(Subscription required.) - ^ Academic scientists and the pharmaceutical industry

- ^ Cannon, Geoffrey (1988). The politics of food. London: Century. p. 161. ISBN 0-7126-1717-5. [better source needed]

- ^ Barrows, Julie N.; Lipman, Arthur L.; Bailey, Catherine J. Cianci, Sebastian (ed.). "Color Additives: FDA's Regulatory Process and Historical Perspectives". Food Safety Magazine. No. October/November 2003. Food Safety Magazine. Retrieved 24 July 2016.

- ^ US FDA Color Additive Status List

- ^ "Red No. 3 and Other Colorful Controversies". FDA. Archived from the original on 2007-08-09. Retrieved 2007-08-26.

FDA terminated the provisional listings for FD&C Red No. 3 on January 29, 1990, at the conclusion of its review of the 200 straight colors on the 1960 provisional list. Commonly called erythrosine, FD&C Red No. 3 is a tint that imparts a watermelon-red color and was one of the original seven colors on Hesse's list.

- ^ a b c d e "Food coloring". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2007-08-21.

Among the colours that have been "delisted," or disallowed, in the United States are FD&C Orange No. 1; FD&C Red No. 32; FD&C Yellows No. 1, 2, 3, and 4; FD&C Violet No. 1; and FD&C Reds No. 2 and 4. Many countries with similar food colouring controls (including Canada and Great Britain) also ban the use of Red No. 40, and Yellow No. 5 is also undergoing testing.

- ^ CFR Title 21 Part 81.10: Termination of provisional listings of color additives.

- ^ Deshpande, S.S., ed. (2002), "8.5.3 Toxicological Characteristics of Colorants Subject to Certification", Handbook of Food Toxicology, Food Science and Technology, CRC Press, p. 234, ISBN 9780824707606

- ^ Delia B Rodriguez-Amaya "Natural food pigments and colorants" Current Opinion in Food Science 2016, Volume 7, Pages 20–26. doi:10.1016/j.cofs.2015.08.004

- ^ Newsome, A. G.,; Culver, C. A.;van Breemen, R. B. "Nature’s palette: the search for natural blue colorants" J Agric Food Chem 2014, volume 62, pp. 6498-6511. doi:10.1021/jf501419q

- ^ "Dye Wool Yarn With Food Colors".

- ^ Feingold, B.F. (1973). Introduction to clinical allergy. Charles C. Thomas. ISBN 0-398-02797-8.

- ^ Tomaska LD and Brooke-Taylor, S. Food Additives - General pp 449-454 in Encyclopedia of Food Safety, Vol 2: Hazards and Diseases. Eds, Motarjemi Y et al. Academic Press, 2013. ISBN 9780123786135

- ^ Kavale KA, Forness SR (1983). "Hyperactivity and Diet Treatment: A Meta-Analysis of the Feingold Hypothesis". Journal of Learning Disabilities. 16 (6): 324–330. doi:10.1177/002221948301600604. ISSN 0022-2194.

- ^ a b c d e f g h FDA. Background Document for the Food Advisory Committee: Certified Color Additives in Food and Possible Association with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Children: March 30-31, 2011

- ^ Millichap JG, Yee MM (February 2012). "The diet factor in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Pediatrics. 129 (2): 330–337. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-2199. PMID 22232312.

- ^ Amchova, Petra; Kotolova, Hana; Ruda-Kucerova, Jana "Health safety issues of synthetic food colorants" Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology (2015), 73(3), 914-922.doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2015.09.026

- ^ a b c Sarah Chapman of Chapman Technologies on behalf of Food Standards Agency in Scotland. March 2011 [Guidelines on approaches to the replacement of Tartrazine, Allura Red, Ponceau 4R, Quinoline Yellow, Sunset Yellow and Carmoisine in food and beverages]

- ^ EFSA Panel on Food Additives and Nutrient Sources added to food (ANS) Scientific Opinion on the re-evaluation of Sunset Yellow FCF (E 110) as a food additive. EFSA Journal 2009; 7(11):1330 doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2009.1330

- ^ EFSA Panel on Food Additives and Nutrient Sources added to Food (ANS) 091113 efsa.europa.eu Scientific Opinion on the re-evaluation of Ponceau 4R (E 124) as a food additive EFSA Journal 2009; 7(11):1328

- ^ EFSA Panel on Food Additives and Nutrient Sources added to food (ANS). Scientific Opinion on the re-evaluation of Quinoline Yellow (E 104) as a food additive. EFSA Journal 2009; 7(11):1329 [40 pp.]. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2009.1329

- ^ EFSA Panel on Food Additives and Nutrient Sources added to Food (ANS) (November 2009). "Scientific Opinion on the re-evaluation Tartrazine (E 102)". EFSA Journal. 7 (11): 1331–1382. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2009.1331.