Formation and evolution of the Solar System: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 174.28.105.206 (talk) to last version by Materialscientist |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

The formation and [[wikt:evolution|evolution]] of the [[Solar System]] is estimated to have begun 4.568 [[1000000000 (number)|billion]] years ago with the [[gravitation]]al collapse of a small part of a giant [[molecular cloud]].<ref>[http://www.nature.com/ngeo/journal/vaop/ncurrent/full/ngeo941.html Bouvier, Audrey and Meenakshi Wadhwa, "The age of the solar system redefined by the oldest Pb-Pb age of a meteoritic inclusion"]. ''Nature Geoscience,'' Nature Publishing Group, a division of Macmillan Publishers Limited. Published online 2010-08-22, retrieved 2010-08-26, doi: 10.1038/NGEO941.<br>Date based on oldest [[inclusion]]s found to date in [[meteorite]]s, thought to be among the first solid material to form in the collapsing [[Nebular hypothesis|solar nebula]].</ref> |

The formation and [[wikt:evolution|evolution]] of the [[Solar System]] is estimated to have begun 4.568 [[1000000000 (number)|billion]] years ago with the [[gravitation]]al collapse of a small part of a giant [[molecular cloud]].<ref>[http://www.nature.com/ngeo/journal/vaop/ncurrent/full/ngeo941.html Bouvier, Audrey and Meenakshi Wadhwa, "The age of the solar system redefined by the oldest Pb-Pb age of a meteoritic inclusion"]. ''Nature Geoscience,'' Nature Publishing Group, a division of Macmillan Publishers Limited. Published online 2010-08-22, retrieved 2010-08-26, doi: 10.1038/NGEO941.<br>Date based on oldest [[inclusion]]s found to date in [[meteorite]]s, thought to be among the first solid material to form in the collapsing [[Nebular hypothesis|solar nebula]].</ref> |

||

Most of the collapsing mass collected in the centre, forming |

Most of the collapsing mass collected in the centre, forming my butt, while the rest flattened into a [[protoplanetary disk]] out of which the [[planet]]s, [[Natural satellite|moons]], [[asteroid]]s, and other [[small Solar System bodies]] formed. |

||

This widely accepted model, known as the [[nebular hypothesis]], was first developed in the 18th century by [[Emanuel Swedenborg]], [[Immanuel Kant]], and [[Pierre-Simon Laplace]]. Its subsequent development has interwoven a variety of scientific disciplines including [[astronomy]], [[physics]], [[geology]], and [[planetary science]]. Since the dawn of the [[space age]] in the 1950s and the discovery of [[extrasolar planets]] in the 1990s, the models have been both challenged and refined to account for new observations. |

This widely accepted model, known as the [[nebular hypothesis]], was first developed in the 18th century by [[Emanuel Swedenborg]], [[Immanuel Kant]], and [[Pierre-Simon Laplace]]. Its subsequent development has interwoven a variety of scientific disciplines including [[astronomy]], [[physics]], [[geology]], and [[planetary science]]. Since the dawn of the [[space age]] in the 1950s and the discovery of [[extrasolar planets]] in the 1990s, the models have been both challenged and refined to account for new observations. |

||

Revision as of 14:29, 9 November 2010

The formation and evolution of the Solar System is estimated to have begun 4.568 billion years ago with the gravitational collapse of a small part of a giant molecular cloud.[1]

Most of the collapsing mass collected in the centre, forming my butt, while the rest flattened into a protoplanetary disk out of which the planets, moons, asteroids, and other small Solar System bodies formed.

This widely accepted model, known as the nebular hypothesis, was first developed in the 18th century by Emanuel Swedenborg, Immanuel Kant, and Pierre-Simon Laplace. Its subsequent development has interwoven a variety of scientific disciplines including astronomy, physics, geology, and planetary science. Since the dawn of the space age in the 1950s and the discovery of extrasolar planets in the 1990s, the models have been both challenged and refined to account for new observations.

The Solar System has evolved considerably since its initial formation. Many moons have formed from circling discs of gas and dust around their parent planets, while other moons are believed to have formed independently and later been captured by their planets. Still others, as the Earth's Moon, may be the result of giant collisions. Collisions between bodies have occurred continually up to the present day and have been central to the evolution of the Solar System. The positions of the planets often shifted, and planets have switched places.[2] This planetary migration now is believed to have been responsible for much of the Solar System's early evolution.

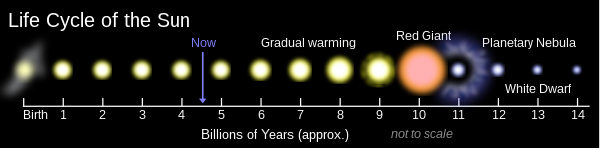

In roughly 5 billion years, the Sun will cool and expand outward to many times its current diameter (becoming a red giant), before casting off its outer layers as a planetary nebula, and leaving behind a stellar corpse known as a white dwarf. In the far distant future, the gravity of passing stars gradually will whittle away at the Sun's retinue of planets. Some planets will be destroyed, others ejected into interstellar space. Ultimately, over the course of trillions of years, it is likely that the Sun will be left alone with no bodies in orbit around it.[3]

History

Ideas concerning the origin and fate of the world date from the earliest known writings; however, for almost all of that time, there was no attempt to link such theories to the existence of a "Solar System", simply because it was not generally believed that the Solar System, in the sense we now understand it, existed. The first step toward a theory of Solar System formation and evolution was the general acceptance of heliocentrism, which placed the Sun at the centre of the system and the Earth in orbit around it. This conception had gestated for millennia (philosophers such as Aristarchus of Samos had suggested it as early as 600 BC), but was widely accepted only by the end of the 17th century. The first recorded use of the term "Solar System" dates from 1704.[4]

The current standard theory for Solar System formation, the nebular hypothesis, has fallen into and out of favour since its formulation by Emanuel Swedenborg, Immanuel Kant, and Pierre-Simon Laplace in the 18th century. The most significant criticism of the hypothesis was its apparent inability to explain the Sun's relative lack of angular momentum when compared to the planets.[5] However, since the early 1980s studies of young stars have shown them to be surrounded by cool discs of dust and gas, exactly as the nebular hypothesis predicts, which has led to its re-acceptance.[6]

Understanding of how the Sun will continue to evolve required an understanding of the source of its power. Arthur Stanley Eddington's confirmation of Albert Einstein's theory of relativity led to his realisation that the Sun's energy comes from nuclear fusion reactions in its core.[7] In 1935, Eddington went further and suggested that other elements also might form within stars.[8] Fred Hoyle elaborated on this premise by arguing that evolved stars called red giants created many elements heavier than hydrogen and helium in their cores. When a red giant finally casts off its outer layers, these elements would then be recycled to form other star systems.[8]

Formation

Pre-solar nebula

The nebular hypothesis maintains that the Solar System formed from the gravitational collapse of a fragment of a giant molecular cloud.[9] The cloud itself had a size of about 20 pc,[9] while the fragments were roughly 1 pc (three and a quarter light-years) across.[10] The further collapse of the fragments led to the formation of dense cores 0.01–0.1 pc (2,000–20,000 AU) in size.[note 1][9][11] One of these collapsing fragments (known as the pre-solar nebula) would form what became the Solar System.[12] The composition of this region with a mass just over that of the Sun was about the same as that of the Sun today, with hydrogen, along with helium and trace amounts of lithium produced by Big Bang nucleosynthesis, forming about 98% of its mass. The remaining 2% of the mass consisted of heavier elements that were created by nucleosynthesis in earlier generations of stars.[13] Late in the life of these stars, they ejected heavier elements into the interstellar medium.[14]

Studies of ancient meteorites reveal traces of stable daughter nuclei of short-lived isotopes, such as iron-60, that only form in exploding, short-lived stars. This indicates that one or more supernovae occurred near the Sun while it was forming. A shock wave from a supernova may have triggered the formation of the Sun by creating regions of over-density within the cloud, causing these regions to collapse.[15] Because only massive, short-lived stars produce supernovae, the Sun must have formed in a large star-forming region that produced massive stars, possibly similar to the Orion Nebula.[16][17] Studies of the structure of the Kuiper belt and of anomalous materials within it suggest that the Sun formed within a cluster of stars with a diameter of between 6.5 and 19.5 light-years and a collective mass equivalent to 3,000 Suns.[18] Several simulations of our young Sun interacting with close-passing stars over the first 100 million years of its life produce anomalous orbits observed in the outer Solar System, such as detached objects.[19]

Because of the conservation of angular momentum, the nebula spun faster as it collapsed. As the material within the nebula condensed, the atoms within it began to collide with increasing frequency, converting their kinetic energy into heat. The centre, where most of the mass collected, became increasingly hotter than the surrounding disc.[10] Over about 100,000 years,[9] the competing forces of gravity, gas pressure, magnetic fields, and rotation caused the contracting nebula to flatten into a spinning protoplanetary disc with a diameter of ~200 AU[10] and form a hot, dense protostar (a star in which hydrogen fusion has not yet begun) at the centre.[20]

At this point in its evolution, the Sun is believed to have been a T Tauri star.[21] Studies of T Tauri stars show that they are often accompanied by discs of pre-planetary matter with masses of 0.001–0.1 solar masses.[22] These discs extend to several hundred AU—the Hubble Space Telescope has observed protoplanetary discs of up to 1000 AU in diameter in star-forming regions such as the Orion Nebula[23]—and are rather cool, reaching only a thousand kelvins at their hottest.[24] Within 50 million years, the temperature and pressure at the core of the Sun became so great that its hydrogen began to fuse, creating an internal source of energy that countered gravitational contraction until hydrostatic equilibrium was achieved.[25] This marked the Sun's entry into the prime phase of its life, known as the main sequence. Main sequence stars derive energy from the fusion of hydrogen into helium in their cores. The Sun remains a main sequence star today.[26]

Formation of planets

The various planets are thought to have formed from the solar nebula, the disc-shaped cloud of gas and dust left over from the Sun's formation.[27] The currently accepted method by which the planets formed is known as accretion, in which the planets began as dust grains in orbit around the central protostar. Through direct contact, these grains formed into clumps up to 200 metres in diameter, which in turn collided to form larger bodies (planetesimals) of ~10 kilometres (km) in size.[28] These gradually increased through further collisions, growing at the rate of centimetres per year over the course of the next few million years.[28]

The inner Solar System, the region of the Solar System inside 4 AU, was too warm for volatile molecules like water and methane to condense, so the planetesimals that formed there could only form from compounds with high melting points, such as metals (like iron, nickel, and aluminium) and rocky silicates. These rocky bodies would become the terrestrial planets (Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars). These compounds are quite rare in the universe, comprising only 0.6% of the mass of the nebula, so the terrestrial planets could not grow very large.[10] The terrestrial embryos grew to about 0.05 Earth masses and ceased accumulating matter about 100,000 years after the formation of the Sun; subsequent collisions and mergers between these planet-sized bodies allowed terrestrial planets to grow to their present sizes (see Terrestrial planets below).[29]

When the terrestrial planets were forming, they remained immersed in a disk of gas and dust. The gas was partially supported by pressure and so did not orbit the Sun as rapidly as the planets. The resulting drag caused a transfer of angular momentum, and as a result the planets gradually migrated to new orbits. Models show that temperature variations in the disk governed this rate of migration, but the net trend was for the inner planets to migrate inward as the disk dissipated, leaving the planets in their current orbits.[30]

The gas giant planets (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune) formed further out, beyond the frost line, the point between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter where the material is cool enough for volatile icy compounds to remain solid. The ices that formed the Jovian planets were more abundant than the metals and silicates that formed the terrestrial planets, allowing the Jovian planets to grow massive enough to capture hydrogen and helium, the lightest and most abundant elements.[10] Planetesimals beyond the frost line accumulated up to four Earth masses within about 3 million years.[29] Today, the four gas giants comprise just under 99% of all the mass orbiting the Sun.[note 2] Theorists believe it is no accident that Jupiter lies just beyond the frost line. Because the frost line accumulated large amounts of water via evaporation from infalling icy material, it created a region of lower pressure that increased the speed of orbiting dust particles and halted their motion toward the Sun. In effect, the frost line acted as a barrier that caused material to accumulate rapidly at ~5 AU from the Sun. This excess material coalesced into a large embryo of about 10 Earth masses, which then began to grow rapidly by swallowing hydrogen from the surrounding disc, reaching 150 Earth masses in only another 1000 years and finally topping out at 318 Earth masses. Saturn may owe its substantially lower mass simply to having formed a few million years after Jupiter, when there was less gas available to consume.[29]

T Tauri stars like the young Sun have far stronger stellar winds than more stable, older stars. Uranus and Neptune are believed to have formed after Jupiter and Saturn did, when the strong solar wind had blown away much of the disc material. As a result, the planets accumulated little hydrogen and helium—not more than 1 Earth mass each. Uranus and Neptune are sometimes referred to as failed cores.[31] The main problem with formation theories for these planets is the timescale of their formation. At the current locations it would have taken a hundred million years for their cores to accrete. This means that Uranus and Neptune probably formed closer to the Sun—near or even between Jupiter and Saturn—and later migrated outward (see Planetary migration below).[31][32] Motion in the planetesimal era was not all inward toward the Sun; the Stardust sample return from Comet Wild 2 has suggested that materials from the early formation of the Solar System migrated from the warmer inner Solar System to the region of the Kuiper belt.[33]

After between three and ten million years,[29] the young Sun's solar wind would have cleared away all the gas and dust in the protoplanetary disc, blowing it into interstellar space, thus ending the growth of the planets.[34][35]

Subsequent evolution

The planets were originally believed to have formed in or near their current orbits. However, this view underwent radical change during the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Currently, it is believed that the Solar System looked very different after its initial formation: several objects at least as massive as Mercury were present in the inner Solar System, the outer Solar System was much more compact than it is now, and the Kuiper belt was much closer to the Sun.[36]

Terrestrial planets

At the end of the planetary formation epoch the inner Solar System was populated by 50–100 Moon- to Mars-sized planetary embryos.[37][38] Further growth was possible only because these bodies collided and merged, which took less than 100 million years. These objects would have gravitationally interacted with one another, tugging at each other's orbits until they collided, growing larger until the four terrestrial planets we know today took shape.[29] One such giant collision is believed to have formed the Moon (see Moons below), while another removed the outer envelope of the young Mercury.[39]

One unresolved issue with this model is that it cannot explain how the initial orbits of the proto-terrestrial planets, which would have needed to be highly eccentric to collide, produced the remarkably stable and near-circular orbits the terrestrial planets possess today.[37] One hypothesis for this "eccentricity dumping" is that the terrestrials formed in a disc of gas still not expelled by the Sun. The "gravitational drag" of this residual gas would have eventually lowered the planets' energy, smoothing out their orbits.[38] However, such gas, if it existed, would have prevented the terrestrials' orbits from becoming so eccentric in the first place.[29] Another hypothesis is that gravitational drag occurred not between the planets and residual gas but between the planets and the remaining small bodies. As the large bodies moved through the crowd of smaller objects, the smaller objects, attracted by the larger planets' gravity, formed a region of higher density, a "gravitational wake", in the larger objects' path. As they did so, the increased gravity of the wake slowed the larger objects down into more regular orbits.[40]

Asteroid belt

The outer edge of the terrestrial region, between 2 and 4 AU from Sun, is called the asteroid belt. The asteroid belt initially contained more than enough matter to form 2–3 Earth-like planets, and, indeed, a large number of planetesimals formed there. As with the terrestrials, planetesimals in this region later coalesced and formed 20–30 Moon- to Mars-sized planetary embryos;[41] however, the proximity of Jupiter meant that after this planet formed, 3 million years after the Sun, the region's history changed dramatically.[37] Orbital resonances with Jupiter and Saturn are particularly strong in the asteroid belt, and gravitational interactions with more massive embryos scattered many planetesimals into those resonances. Jupiter's gravity increased the velocity of objects within these resonances, causing them to shatter upon collision with other bodies, rather than accrete.[42]

As Jupiter migrated inward following its formation (see Planetary migration below), resonances would have swept across the asteroid belt, dynamically exciting the region's population and increasing their velocities relative to each other.[43] The cumulative action of the resonances and the embryos either scattered the planetesimals away from the asteroid belt or excited their orbital inclinations and eccentricities.[41][44] Some of those massive embryos too were ejected by Jupiter, while others may have migrated to the inner Solar System and played a role in the final accretion of the terrestrial planets.[41][45][46] During this primary depletion period, the effects of the giant planets and planetary embryos left the asteroid belt with a total mass equivalent to less than 1% that of the Earth, composed mainly of small planetesimals.[44] This is still 10–20 times more than the current mass in the main belt, which is about 1/2,000 the Earth's mass.[47] A secondary depletion period that brought the asteroid belt down close to its present mass is believed to have followed when Jupiter and Saturn entered a temporary 2:1 orbital resonance (see below).

The inner Solar System's period of giant impacts probably played a role in the Earth acquiring its current water content (~6×1021 kg) from the early asteroid belt. Water is too volatile to have been present at Earth's formation and must have been subsequently delivered from outer, colder parts of the Solar System.[48] The water was probably delivered by planetary embryos and small planetesimals thrown out of the asteroid belt by Jupiter.[45] A population of main-belt comets discovered in 2006 has been also suggested as a possible source for Earth's water.[48][49] In contrast, comets from the Kuiper belt or farther regions delivered not more than about 6% of Earth's water.[2][50] The panspermia hypothesis holds that life itself may have been deposited on Earth in this way, although this idea is not widely accepted.[51]

Planetary migration

According to the nebular hypothesis, the outer two planets are in the "wrong place". Uranus and Neptune (known as the "ice giants") exist in a region where the reduced density of the solar nebula and longer orbital times render their formation highly implausible.[52] The two are instead believed to have formed in orbits near Jupiter and Saturn, where more material was available, but to have migrated outward to their current positions over hundreds of millions of years.[31]

The migration of the outer planets is also necessary to account for the existence and properties of the Solar System's outermost regions.[32] Beyond Neptune, the Solar System continues into the Kuiper belt, the scattered disc, and the Oort cloud, three sparse populations of small icy bodies thought to be the points of origin for most observed comets. At their distance from the Sun, accretion was too slow to allow planets to form before the solar nebula dispersed, and thus the initial disc lacked enough mass density to consolidate into a planet.[52] The Kuiper belt lies between 30 and 55 AU from the Sun, while the farther scattered disc extends to over 100 AU,[32] and the distant Oort cloud begins at about 50,000 AU.[53] Originally, however, the Kuiper belt was much denser and closer to the Sun, with an outer edge at approximately 30 AU. Its inner edge would have been just beyond the orbits of Uranus and Neptune, which were in turn far closer to the Sun when they formed (most likely in the range of 15–20 AU), and in opposite locations, with Uranus farther from the Sun than Neptune.[2][32]

After the formation of the Solar System, the orbits of all the giant planets continued to change slowly, influenced by their interaction with large number of remaining planetesimals. After 500–600 million years (about 4 billion years ago) Jupiter and Saturn fell into a 2:1 resonance; Saturn orbited the Sun once for every two Jupiter orbits.[32] This resonance created a gravitational push against the outer planets, causing Neptune to surge past Uranus and plough into the ancient Kuiper belt. The planets scattered the majority of the small icy bodies inwards, while themselves moving outwards. These planetesimals then scattered off the next planet they encountered in a similar manner, moving the planets' orbits outwards while they moved inwards.[32] This process continued until the planetesimals interacted with Jupiter, whose immense gravity sent them into highly elliptical orbits or even ejected them outright from the Solar System. This caused Jupiter to move slightly inward.[note 3] Those objects scattered by Jupiter into highly elliptical orbits formed the Oort cloud;[32] those objects scattered to a lesser degree by the migrating Neptune formed the current Kuiper belt and scattered disc.[32] This scenario explains the Kuiper belt's and scattered disc's present low mass. Some of the scattered objects, including Pluto, became gravitationally tied to Neptune's orbit, forcing them into mean-motion resonances.[54] Eventually, friction within the planetesimal disc made the orbits of Uranus and Neptune circular again.[32][55]

In contrast to the outer planets, the inner planets are not believed to have migrated significantly over the age of the Solar System, because their orbits have remained stable following the period of giant impacts.[29]

Late Heavy Bombardment and after

Gravitational disruption from the outer planets' migration would have sent large numbers of asteroids into the inner Solar System, severely depleting the original belt until it reached today's extremely low mass.[44] This event may have triggered the Late Heavy Bombardment that occurred approximately 4 billion years ago, 500–600 million years after the formation of the Solar System.[2][56] This period of heavy bombardment lasted several hundred million years and is evident in the cratering still visible on geologically dead bodies of the inner Solar System such as the Moon and Mercury.[2][57] The oldest known evidence for life on Earth dates to 3.8 billion years ago—almost immediately after the end of the Late Heavy Bombardment.[58]

Impacts are believed to be a regular (if currently infrequent) part of the evolution of the Solar System. That they continue to happen is evidenced by the collision of Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 with Jupiter in 1994, the 2009 Jupiter impact event, and the impact feature Meteor Crater in Arizona. The process of accretion, therefore, is not complete, and may still pose a threat to life on Earth.[59][60]

Over the course of the Solar System's evolution, comets were ejected out of the inner Solar System by the gravity of the giant planets, and sent thousands of AU outward to form the Oort cloud, a spherical outer swarm of cometary nuclei at the farthest extent of the Sun's gravitational pull. Eventually, after about 800 million years, the gravitational disruption caused by galactic tides, passing stars and giant molecular clouds began to deplete the cloud, sending comets into the inner Solar System.[61] The evolution of the outer Solar System also appears to have been influenced by space weathering from the solar wind, micrometeorites, and the neutral components of the interstellar medium.[62]

The evolution of the asteroid belt after Late Heavy Bombardment was mainly governed by collisions.[63] Objects with large mass have enough gravity to retain any material ejected by a violent collision. In the asteroid belt this usually is not the case. As a result, many larger objects have been broken apart, and sometimes newer objects have been forged from the remnants in less violent collisions.[63] Moons around some asteroids currently can only be explained as consolidations of material flung away from the parent object without enough energy to entirely escape its gravity.[64]

Moons

Moons have come to exist around most planets and many other Solar System bodies. These natural satellites originated by one of three possible mechanisms:

- co-formation from a circum-planetary disc (only in the cases of the gas giants);

- formation from impact debris (given a large enough impact at a shallow angle); and

- capture of a passing object.

Jupiter and Saturn have a number of large moons, such as Io, Europa, Ganymede and Titan, which may have originated from discs around each giant planet in much the same way that the planets formed from the disc around the Sun.[65] This origin is indicated by the large sizes of the moons and their proximity to the planet. These attributes are impossible to achieve via capture, while the gaseous nature of the primaries make formation from collision debris another impossibility. The outer moons of the gas giants tend to be small and have eccentric orbits with arbitrary inclinations. These are the characteristics expected of captured bodies.[66][67] Most such moons orbit in the direction opposite the rotation of their primary. The largest irregular moon is Neptune's moon Triton, which is believed to be a captured Kuiper belt object.[60]

Moons of solid Solar System bodies have been created by both collisions and capture. Mars's two small moons, Deimos and Phobos, are believed to be captured asteroids.[68] The Earth's Moon is believed to have formed as a result of a single, large oblique collision.[69][70] The impacting object likely had a mass comparable to that of Mars, and the impact probably occurred near the end of the period of giant impacts. The collision kicked into orbit some of the impactor's mantle, which then coalesced into the Moon.[69] The impact was probably the last in the series of mergers that formed the Earth. It has been further hypothesized that the Mars-sized object may have formed at one of the stable Earth-Sun Lagrangian points (either L4 or L5) and drifted from its position.[71] Pluto's moon Charon may also have formed by means of a large collision; the Pluto-Charon and Earth-Moon systems are the only two in the Solar System in which the satellite's mass is at least 1% that of the larger body.[72]

Future

Astronomers estimate that the Solar System as we know it today will not change drastically until the Sun has fused all the hydrogen fuel in its core into helium, beginning its evolution from the main sequence of the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram and into its red giant phase. Even so, the Solar System will continue to evolve until then.

Long-term stability

The Solar System is chaotic,[73] with the orbits of the planets open to long-term variations. One notable example of this chaos is the Neptune-Pluto system, which lies in a 3:2 orbital resonance. Although the resonance itself will remain stable, it becomes impossible to predict the position of Pluto with any degree of accuracy more than 10–20 million years (the Lyapunov time) into the future.[74] Another example is Earth's axial tilt which, thanks to friction raised within Earth's mantle by tidal interactions with the Moon (see below) will be incomputable at some point between 1.5 and 4.5 billion years from now.[75]

The outer planets' orbits are chaotic over longer timescales, such that they possess a Lyapunov time in the range of 2–230 million years.[76] In all cases this means that the position of a planet along its orbit ultimately becomes impossible to predict with any certainty (so, for example, the timing of winter and summer become uncertain), but in some cases the orbits themselves may change dramatically. Such chaos manifests most strongly as changes in eccentricity, with some planets' orbits becoming significantly more—or less—elliptical.[77]

Ultimately, the Solar System is stable in that none of the planets will collide with each other or be ejected from the system in the next few billion years.[76] Beyond this, within five billion years or so Mars's eccentricity may grow to around 0.2, such that it lies on an Earth-crossing orbit, leading to a potential collision. In the same timescale, Mercury's eccentricity may grow even further, and a close encounter with Venus could theoretically eject it from the Solar System altogether[73] or send it on a collision course with Venus or Earth.[78]

Moon-ring systems

The evolution of moon systems is driven by tidal forces. A moon will raise a tidal bulge in the object it orbits (the primary) due to the differential gravitational force across diameter of the primary. If a moon is revolving in the same direction as the planet's rotation and the planet is rotating faster than the orbital period of the moon, the bulge will constantly be pulled ahead of the moon. In this situation, angular momentum is transferred from the rotation of the primary to the revolution of the satellite. The moon gains energy and gradually spirals outward, while the primary rotates more slowly over time.

The Earth and its Moon are one example of this configuration. Today, the Moon is tidally locked to the Earth; one of its revolutions around the Earth (currently about 29 days) is equal to one of its rotations about its axis, so it always shows one face to the Earth. The Moon will continue to recede from Earth, and Earth's spin will continue to slow gradually. In about 50 billion years, if they survive the Sun's expansion, the Earth and Moon will become tidally locked to each other; each will be caught up in what is called a "spin–orbit resonance" in which the Moon will circle the Earth in about 47 days and both Moon and Earth will rotate around their axes in the same time, each only visible from one hemisphere of the other.[79][80] Other examples are the Galilean moons of Jupiter (as well as many of Jupiter's smaller moons)[81] and most of the larger moons of Saturn.[82]

A different scenario occurs when the moon is either revolving around the primary faster than the primary rotates, or is revolving in the direction opposite the planet's rotation. In these cases, the tidal bulge lags behind the moon in its orbit. In the former case, the direction of angular momentum transfer is reversed, so the rotation of the primary speeds up while the satellite's orbit shrinks. In the latter case, the angular momentum of the rotation and revolution have opposite signs, so transfer leads to decreases in the magnitude of each (that cancel each other out).[note 4] In both cases, tidal deceleration causes the moon to spiral in towards the primary until it either is torn apart by tidal stresses, potentially creating a planetary ring system, or crashes into the planet's surface or atmosphere. Such a fate awaits the moons Phobos of Mars (within 30 to 50 million years),[83] Triton of Neptune (in 3.6 billion years),[84] Metis and Adrastea of Jupiter,[85] and at least 16 small satellites of Uranus and Neptune. Uranus' Desdemona may even collide with one of its neighboring moons.[86]

A third possibility is where the primary and moon are tidally locked to each other. In that case, the tidal bulge stays directly under the moon, there is no transfer of angular momentum, and the orbital period will not change. Pluto and Charon are an example of this type of configuration.[87]

Prior to the 2004 arrival of the Cassini–Huygens spacecraft, the rings of Saturn were widely thought to be much younger than the Solar System and were not expected to survive beyond another 300 million years. Gravitational interactions with Saturn's moons were expected to gradually sweep the rings' outer edge toward the planet, with abrasion by meteorites and Saturn's gravity eventually taking the rest, leaving Saturn unadorned.[88] However, data from the Cassini mission led scientists to revise that early view. Observations revealed 10 km-wide icy clumps of material that repeatedly break apart and reform, keeping the rings fresh. Saturn's rings are far more massive than the rings of the other gas giants. This large mass is believed to have preserved Saturn's rings since the planet first formed 4.5 billion years ago, and is likely to preserve them for billions of years to come.[89]

The Sun and planetary environments

In the long term, the greatest changes in the Solar System will come from changes in the Sun itself as it ages. As the Sun burns through its supply of hydrogen fuel, it gets hotter and burns the remaining fuel even faster. As a result, the Sun is growing brighter at a rate of ten percent every 1.1 billion years.[90] In one billion years' time, as the Sun's radiation output increases, its circumstellar habitable zone will move outwards, making the Earth's surface hot enough that liquid water can no longer exist there naturally. At this point, all life on land will become extinct.[91] Evaporation of water, a potent greenhouse gas, from the oceans' surface could accelerate temperature increase, potentially ending all life on Earth even sooner.[92] During this time, it is possible that as Mars's surface temperature gradually rises, carbon dioxide and water currently frozen under the surface soil will release into the atmosphere, creating a greenhouse effect that will heat the planet until it achieves conditions parallel to Earth today, providing a potential future abode for life.[93] By 3.5 billion years from now, Earth's surface conditions will be similar to those of Venus today.[90]

Around 5.4 billion years from now, the core of the Sun will become hot enough to trigger hydrogen fusion in its surrounding shell.[91] This will cause the outer layers of the star to expand greatly, and the star will enter a phase of its life in which it is called a red giant.[94][95] Within 7.5 billion years, the Sun will have expanded to a radius of 1.2 AU—256 times its current size. At the tip of the red giant branch, as a result of the vastly increased surface area, the Sun's surface will be much cooler (about 2600 K) than now and its luminosity much higher—up to 2,700 current solar luminosities. For part of its red giant life, the Sun will have a strong stellar wind that will carry away around 33% of its mass.[91][96][97] During these times, it is possible that Saturn's moon Titan could achieve surface temperatures necessary to support life.[98][99]

As the Sun expands, it will swallow the planets Mercury and, most likely, Venus.[100] Earth's fate is less clear; although the Sun will envelop Earth's current orbit, the star's loss of mass (and thus weaker gravity) will cause the planets' orbits to move farther out.[91] If it were only for this, Venus and Earth would probably escape incineration,[96] but a 2008 study suggests that Earth will likely be swallowed up as a result of tidal interactions with the Sun's weakly bound outer envelope.[91]

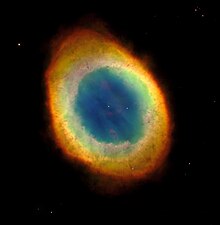

Gradually, the hydrogen burning in the shell around the solar core will increase the mass of the core until it reaches about 45% of the present solar mass. At this point the density and temperature will become so high that the fusion of helium into carbon will begin, leading to a helium flash; the Sun will shrink from around 250 to 11 times its present (main sequence) radius. Consequently, its luminosity will decrease from around 3,000 to 54 times its current level, and its surface temperature will increase to about 4770 K. The Sun will become a horizontal branch star, burning helium in its core in a stable fashion much like it burns hydrogen today. The helium-fusing stage will last only 100 million years. Eventually, it will have to again resort to the reserves of hydrogen and helium in its outer layers and will expand a second time, turning into what is known as an asymptotic giant branch star. Here the luminosity of the Sun will increase again, reaching about 2,090 present luminosities, and it will cool to about 3500 K.[91] This phase lasts about 30 million years, after which, over the course of a further 100,000 years, the Sun's remaining outer layers will fall away, ejecting a vast stream of matter into space and forming a halo known (misleadingly) as a planetary nebula. The ejected material will contain the helium and carbon produced by the Sun's nuclear reactions, continuing the enrichment of the interstellar medium with heavy elements for future generations of stars.[101]

This is a relatively peaceful event, nothing akin to a supernova, which our Sun is too small to undergo as part of its evolution. Any observer present to witness this occurrence would see a massive increase in the speed of the solar wind, but not enough to destroy a planet completely. However, the star's loss of mass could send the orbits of the surviving planets into chaos, causing some to collide, others to be ejected from the Solar System, and still others to be torn apart by tidal interactions.[102] Afterwards, all that will remain of the Sun is a white dwarf, an extraordinarily dense object, 54% its original mass but only the size of the Earth. Initially, this white dwarf may be 100 times as luminous as the Sun is now. It will consist entirely of degenerate carbon and oxygen, but will never reach temperatures hot enough to fuse these elements. Thus the white dwarf Sun will gradually cool, growing dimmer and dimmer.[103]

As the Sun dies, its gravitational pull on the orbiting bodies such as planets, comets and asteroids will weaken due to its mass loss. All remaining planets' orbits will expand; if Venus, Earth, and Mars still exist, their orbits will lie roughly at 1.4 AU (210,000,000 km), 1.9 AU (280,000,000 km), and 2.8 AU (420,000,000 km). They and the other remaining planets will become dark, frigid hulks, completely devoid of any form of life.[96] They will continue to orbit their star, their speed slowed due to their increased distance from the Sun and the Sun's reduced gravity. Two billion years later, when the Sun has cooled to the 6000–8000K range, the carbon and oxygen in the Sun's core will freeze, with over 90% of its remaining mass assuming a crystalline structure.[104] Eventually, after trillions more years, the Sun will finally cease to shine altogether, becoming a black dwarf.[105]

Galactic interaction

The Solar System travels alone through the Milky Way galaxy in a circular orbit approximately 30,000 light years from the galactic centre. Its speed is about 220 km/s. The period required for the Solar System to complete one revolution around the galactic centre, the galactic year, is in the range of 220–250 million years. Since its formation, the Solar System has completed at least 20 such revolutions.[106]

A number of scientists have speculated that the Solar System's path through the galaxy is a factor in the periodicity of mass extinctions observed in the Earth's fossil record. One hypothesis supposes that vertical oscillations made by the Sun as it orbits the galactic centre cause it to regularly pass through the galactic plane. When the Sun's orbit takes it outside the galactic disc, the influence of the galactic tide is weaker; as it re-enters the galactic disc, as it does every 20–25 million years, it comes under the influence of the far stronger "disc tides", which, according to mathematical models, increase the flux of Oort cloud comets into the Solar System by a factor of 4, leading to a massive increase in the likelihood of a devastating impact.[107]

However, others argue that the Sun is currently close to the galactic plane, and yet the last great extinction event was 15 million years ago. Therefore the Sun's vertical position cannot alone explain such periodic extinctions, and that extinctions instead occur when the Sun passes through the galaxy's spiral arms. Spiral arms are home not only to larger numbers of molecular clouds, whose gravity may distort the Oort cloud, but also to higher concentrations of bright blue giant stars, which live for relatively short periods and then explode violently as supernovae.[108]

Galactic collision and planetary disruption

Although the vast majority of galaxies in the Universe are moving away from the Milky Way, the Andromeda Galaxy, the largest member of our Local Group of galaxies, is heading towards it at about 120 km/s.[109] In 2 billion years, Andromeda and the Milky Way will collide, causing both to deform as tidal forces distort their outer arms into vast tidal tails. If this initial disruption occurs, astronomers calculate a 12% chance that the Solar System will be pulled outward into the Milky Way's tidal tail and a 3% chance that it will become gravitationally bound to Andromeda and thus a part of that galaxy.[109] After a further series of glancing blows, during which the likelihood of the Solar System's ejection rises to 30%,[110] the galaxies' supermassive black holes will merge. Eventually, in roughly 7 billion years, the Milky Way and Andromeda will complete their merger into a giant elliptical galaxy. During the merger, if there is enough gas, the increased gravity will force the gas to the centre of the forming elliptical galaxy. This may lead to a short period of intensive star formation called a starburst.[109] In addition the infalling gas will feed the newly formed black hole transforming it into an active galactic nucleus. The force of these interactions will likely push the Solar System into the new galaxy's outer halo, leaving it relatively unscathed by the radiation from these collisions.[109][110]

It is a common misconception that this collision will disrupt the orbits of the planets in the Solar System. While it is true that the gravity of passing stars can detach planets into interstellar space, distances between stars are so great that the likelihood of the Milky Way-Andromeda collision causing such disruption to any individual star system is negligible. While the Solar System as a whole could be affected by these events, the Sun and planets are not expected to be disturbed.[111]

However, over time, the cumulative probability of a chance encounter with a star increases, and disruption of the planets becomes all but inevitable. Assuming that the Big Crunch or Big Rip scenarios for the end of the universe do not occur, calculations suggest that the gravity of passing stars will have completely stripped the dead Sun of its remaining planets within 1 quadrillion (1015) years. This point marks the end of the Solar System. While the Sun and planets may survive, the Solar System, in any meaningful sense, will cease to exist.[3]

Chronology

The time frame of the Solar System's formation has been determined using radiometric dating. Scientists estimate that the Solar System is 4.6 billion years old. The oldest known mineral grains on Earth are approximately 4.4 billion years old.[112] Rocks this old are rare, as Earth's surface is constantly being reshaped by erosion, volcanism, and plate tectonics. To estimate the age of the Solar System, scientists use meteorites, which were formed during the early condensation of the solar nebula. Almost all meteorites (see the Canyon Diablo meteorite) are found to have an age of 4.6 billion years, suggesting that the Solar System must be at least this old.[113]

Studies of discs around other stars have also done much to establish a time frame for Solar System formation. Stars between one and three million years old possess discs rich in gas, whereas discs around stars more than 10 million years old have little to no gas, suggesting that gas giant planets within them have ceased forming.[29]

Timeline of Solar System evolution

Note: All dates and times in this chronology are approximate and should be taken as an order of magnitude indicator only.

| Phase | Time since formation of the Sun | Event |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-Solar System | Billions of years before the formation of the Solar System | Previous generations of stars live and die, injecting heavy elements into the interstellar medium out of which the Solar System formed.[14] |

| ~ 50 million years before formation of the Solar System | If the Solar System formed in an Orion nebula-like star-forming region, the most massive stars are formed, live their lives, die, and explode in supernovae. One particular supernova, called the primal supernova, possibly triggers the formation of the Solar System.[16][17] | |

| Formation of Sun | 0–100,000 years | Pre-solar nebula forms and begins to collapse. Sun begins to form.[29] |

| 100,000 – 50 million years | Sun is a T Tauri protostar.[9] | |

| 100,000 - 10 million years | Outer planets form. By 10 million years, gas in the protoplanetary disc has been blown away, and outer planet formation is likely complete.[29] | |

| 10 million - 100 million years | Terrestrial planets and the Moon form. Giant impacts occur. Water delivered to Earth.[2] | |

| Main sequence | 50 million years | Sun becomes a main sequence star.[25] |

| 200 million years | Oldest known rocks on the Earth formed.[112] | |

| 500 million – 600 million years | Resonance in Jupiter and Saturn's orbits moves Neptune out into the Kuiper belt. Late Heavy Bombardment occurs in the inner Solar System.[2] | |

| 800 million years | Oldest known life on Earth.[58] Oort cloud reaches maximum mass.[61] | |

| 4.6 billion years | Today. Sun remains a main sequence star, continually growing warmer and brighter by ~10% every 1 billion years.[90] | |

| 6 billion years | Sun's habitable zone moves outside of the Earth's orbit, possibly shifting onto Mars' orbit.[93] | |

| 7 billion years | The Milky Way and Andromeda Galaxy begin to collide. Slight chance the Solar System could be captured by Andromeda before the two galaxies fuse completely.[109] | |

| Post-main sequence | 10 billion – 12 billion years | Sun starts burning hydrogen in a shell surrounding its core, ending its main sequence life. Sun begins to ascend the red giant branch of the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram, growing dramatically more luminous (by a factor of up to 2,700), larger (by a factor of up to 250 in radius), and cooler (down to 2600 K): Sun is now a red giant. Mercury and possibly Venus and Earth are swallowed.[91][96] Saturn's moon Titan may become habitable.[98] |

| ~ 12 billion years | Sun passes through helium-burning horizontal branch and asymptotic giant branch phases, losing a total of ~30% of its mass in all post-main sequence phases. Asymptotic giant branch phase ends with the ejection of a planetary nebula, leaving the core of the Sun behind as a white dwarf.[91][101] | |

| Remnant Sun | > 12 billion years | The white dwarf Sun, no longer producing energy, begins to cool and dim continuously; this continues for trillions of years, eventually reaching a black dwarf state.[103][105] |

| ~ 1 quadrillion years (1015 years) | Sun cools to 5 K.[114] Gravity of passing stars detaches planets from orbits. Solar System ceases to exist.[3] |

See also

Notes

- ^ An astronomical unit, or AU, is the average distance between the Earth and the Sun, or ~150 million kilometres. It is the standard unit of measurement for interplanetary distances.

- ^ Combined mass of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune= 445.6 Earth masses. Mass of remaining material= ~5.26 Earth masses or 1.1% (see Solar System#Notes and List of Solar System objects by mass)

- ^ The reason that Saturn, Uranus and Neptune all moved outward whereas Jupiter moved inward is that Jupiter is massive enough to eject planetesimals from the Solar System, while the other three outer planets are not. To eject an object from the Solar System, Jupiter transfers energy to it, and so loses some of its own orbital energy and moves inwards. When Neptune, Uranus and Saturn perturb planetesimals outwards, those planetesimals end up in highly eccentric but still bound orbits, and so can return to the perturbing planet and possibly return its lost energy. On the other hand, when Neptune, Uranus and Saturn perturb objects inwards, those planets gain energy by doing so and therefore move outwards. More importantly, an object being perturbed inwards stands a greater chance of encountering Jupiter and being ejected from the Solar System, in which case the energy gains of Neptune, Uranus and Saturn obtained from their inwards deflections of the ejcted object become permanent.

- ^ In all of these cases of transfer of angular momentum and energy, the angular momentum of the two-body system is conserved. In contrast, the summed energy of the moon's revolution plus the primary's rotation is not conserved, but decreases over time, due to dissipation via frictional heat generated by the movement of the tidal bulge through the body of the primary. If the primary were a frictionless ideal fluid, the tidal bulge would be centered under the satellite, and no transfer would take place. It is the loss of dynamical energy through friction that makes transfer of angular momentum possible.

References

- ^ Bouvier, Audrey and Meenakshi Wadhwa, "The age of the solar system redefined by the oldest Pb-Pb age of a meteoritic inclusion". Nature Geoscience, Nature Publishing Group, a division of Macmillan Publishers Limited. Published online 2010-08-22, retrieved 2010-08-26, doi: 10.1038/NGEO941.

Date based on oldest inclusions found to date in meteorites, thought to be among the first solid material to form in the collapsing solar nebula. - ^ a b c d e f g h R. Gomes, H. F. Levison, K. Tsiganis, A. Morbidelli (2005). "Origin of the cataclysmic Late Heavy Bombardment period of the terrestrial planets" (PDF). Nature. 435 (7041): 466. doi:10.1038/nature03676. PMID 15917802.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Freeman Dyson (July 1979). "Time Without End: Physics and Biology in an open universe". Reviews of Modern Physics. 51 (3): 447. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.51.447. Retrieved 2008-04-02.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|work=and|journal=specified (help) - ^ ""Solar system"". Merriam Webster Online Dictionary. 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-15.

- ^ M. M. Woolfson (1984). "Rotation in the Solar System". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 313: 5. doi:10.1098/rsta.1984.0078.

- ^ Nigel Henbest (1991). "Birth of the planets: The Earth and its fellow planets may be survivors from a time when planets ricocheted around the Sun like ball bearings on a pinball table". New Scientist. Retrieved 2008-04-18.

- ^ David Whitehouse (2005). The Sun: A Biography. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-0470092972.

- ^ a b Simon Mitton (2005). "Origin of the Chemical Elements". Fred Hoyle: A Life in Science. Aurum. pp. 197–222. ISBN 978-1854109613.

- ^ a b c d e Thierry Montmerle, Jean-Charles Augereau, Marc Chaussidon (2006). "Solar System Formation and Early Evolution: the First 100 Million Years". Earth, Moon, and Planets. 98. Spinger: 39–95. doi:10.1007/s11038-006-9087-5.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e Ann Zabludoff (University of Arizona) (Spring 2003). "Lecture 13: The Nebular Theory of the origin of the Solar System". Retrieved 2006-12-27.

- ^ J. J. Rawal (1986). "Further Considerations on Contracting Solar Nebula" (PDF). Earth, Moon, and Planets. 34 (1). Springer Netherlands: 93–100. doi:10.1007/BF00054038. Retrieved 2006-12-27.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|work=and|journal=specified (help) - ^ W. M. Irvine (1983). "The chemical composition of the pre-solar nebula". In T. I. Gombosi (ed.) (ed.). Cometary Exploration. Vol. 1. pp. 3–12.

{{cite conference}}:|editor=has generic name (help); Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Zeilik & Gregory (1998, p. 207)

- ^ a b Charles H. Lineweaver (2001). "An Estimate of the Age Distribution of Terrestrial Planets in the Universe: Quantifying Metallicity as a Selection Effect". Icarus. 151: 307. doi:10.1006/icar.2001.6607. arXiv:astro-ph/0012399.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1080/00107511003764725, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1080/00107511003764725instead. - ^ a b J. Jeff Hester, Steven J. Desch, Kevin R. Healy, Laurie A. Leshin (21 May 2004). "The Cradle of the Solar System". Science. 304 (5674): 1116–1117. doi:10.1126/science.1096808. PMID 15155936.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Martin Bizzarro, David Ulfbeck, Anne Trinquier, Kristine Thrane, James N. Connelly, Bradley S. Meyer (2007). "Evidence for a Late Supernova Injection of 60Fe into the Protoplanetary Disk" (abstract page). Science. 316 (5828): 1178–1181. doi:10.1126/science.1141040. PMID 17525336.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Simon F. Portegies Zwart (2009). "The Lost Siblings of the Sun". Astrophysical Journal. 696 (L13 – L16): L13. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/696/1/L13.

- ^ Nathan A. Kaib and Thomas Quinn (2008). "The formation of the Oort cloud in open cluster environments". Icarus. 197 (1): 221–238. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2008.03.020.

- ^ Jane S. Greaves (2005). "Disks Around Stars and the Growth of Planetary Systems". Science. 307 (5706): 68. doi:10.1126/science.1101979. PMID 15637266.

- ^ Caffe, M. W.; Hohenberg, C. M.; Swindle, T. D.; Goswami, J. N. (February 1, 1987). "Evidence in meteorites for an active early sun". Astrophysical Journal, Part 2 - Letters to the Editor. 313: L31 – L35. Bibcode:1987ApJ...313L..31C. doi:10.1086/184826.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ M. Momose, Y. Kitamura, S. Yokogawa, R. Kawabe, M. Tamura, S. Ida (2003). "Investigation of the Physical Properties of Protoplanetary Disks around T Tauri Stars by a High-resolution Imaging Survey at lambda = 2 mm" (PDF). In Ikeuchi, S., Hearnshaw, J. and Hanawa, T. (eds.) (ed.). The Proceedings of the IAU 8th Asian-Pacific Regional Meeting, Volume I. Vol. 289. Astronomical Society of the Pacific Conference Series. p. 85.

{{cite conference}}:|editor=has generic name (help); Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Deborah L. Padgett, Wolfgang Brandner, Karl R. Stapelfeldt; et al. (1999). "Hubble Space Telescope/NICMOS Imaging of Disks and Envelopes around Very Young Stars". The Astronomical Journal. 117: 1490–1504. doi:10.1086/300781.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ M. Küker, T. Henning, G. Rüdiger (2003). "Magnetic Star-Disk Coupling in Classical T Tauri Systems". Astrophysical Journal. 589: 397. doi:10.1086/374408.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Sukyoung Yi, Pierre Demarque, Yong-Cheol Kim, Young-Wook Lee, Chang H. Ree, Thibault Lejeune, Sydney Barnes (2001). "Toward Better Age Estimates for Stellar Populations: The Isochrones for Solar Mixture". Astrophysical Journal Supplement. 136: 417. doi:10.1086/321795. arXiv:astro-ph/0104292.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zeilik & Gregory (1998, p. 320)

- ^ A. P. Boss, R. H. Durisen (2005). "Chondrule-forming Shock Fronts in the Solar Nebula: A Possible Unified Scenario for Planet and Chondrite Formation" (abstract page). The Astrophysical Journal. 621: L137 – L140. doi:10.1086/429160.

- ^ a b P. Goldreich, W. R. Ward (1973). "The Formation of Planetesimals". Astrophysical Journal. 183: 1051. doi:10.1086/152291. Retrieved 2006-11-16.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Douglas N. C. Lin (May 2008). "The Genesis of Planets" (fee required). Scientific American. 298 (5): 50–59. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0508-50. PMID 18444325.

- ^ Staff. "How Earth Survived Birth". Astrobiology Magazine. Retrieved 2010-02-04.

- ^ a b c E. W. Thommes, M. J. Duncan, H. F. Levison (2002). "The Formation of Uranus and Neptune among Jupiter and Saturn". Astronomical Journal. 123: 2862. doi:10.1086/339975. arXiv:astro-ph/0111290.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i Harold F. Levison, Alessandro Morbidelli, Crista Van Laerhoven; et al. (2007). "Origin of the Structure of the Kuiper Belt during a Dynamical Instability in the Orbits of Uranus and Neptune". Icarus. 196: 258. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2007.11.035. arXiv:0712.0553.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Emily Lakdawalla (2006). "Stardust Results in a Nutshell: The Solar Nebula was Like a Blender". The Planetary Society. Retrieved 2007-01-02.

- ^ B. G. Elmegreen (1979). "On the disruption of a protoplanetary disc nebula by a T Tauri like solar wind". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 80: 77. Retrieved 2006-11-19.

- ^ Heng Hao (24 November 2004). "Disc-Protoplanet interactions" (PDF). Harvard University. Retrieved 2006-11-19.

- ^ Mike Brown (California Institute of Technology). "Dysnomia, the moon of Eris". Personal web site. Retrieved 2008-02-01.

- ^ a b c Jean-Marc Petit, Alessandro Morbidelli (2001). "The Primordial Excitation and Clearing of the Asteroid Belt" (PDF). Icarus. 153: 338–347. doi:10.1006/icar.2001.6702.

- ^ a b Junko Kominami, Shigeru Ida (2001). "The Effect of Tidal Interaction with a Gas Disk on Formation of Terrestrial Planets". Icarus. 157 (1): 43–56. doi:10.1006/icar.2001.6811.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|work=and|journal=specified (help) - ^ Sean C. Solomon (2003). "Mercury: the enigmatic innermost planet". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 216: 441–455. doi:10.1016/S0012-821X(03)00546-6.

- ^ Peter Goldreich, Yoram Lithwick, Re’em Sari (10 October 2004). "Final Stages of Planet Formation". The Astrophysical Journal. 614: 497. doi:10.1086/423612.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c William F. Bottke, Daniel D. Durda, David Nesvorny; et al. (2005). "Linking the collisional history of the main asteroid belt to its dynamical excitation and depletion" (PDF). Icarus. 179: 63–94. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2005.05.017.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ R. Edgar, P. Artymowicz (2004). "Pumping of a Planetesimal Disc by a Rapidly Migrating Planet" (PDF). Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 354: 769–772. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2004.08238.x. Retrieved 2008-05-12.

- ^ E. R. D. Scott (2006). "Constraints on Jupiter's Age and Formation Mechanism and the Nebula Lifetime from Chondrites and Asteroids". Proceedings 37th Annual Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. League City, Texas: Lunar and Planetary Society. Retrieved 2007-04-16.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c David O’Brien, Alessandro Morbidelli, William F. Bottke (2007). "The primordial excitation and clearing of the asteroid belt—Revisited" (PDF). Icarus. 191: 434–452. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2007.05.005.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Sean N. Raymond, Thomas Quinn, Jonathan I. Lunine (2007). "High-resolution simulations of the final assembly of Earth-like planets 2: water delivery and planetary habitability". Astrobiology. 7 (1): 66–84. doi:10.1089/ast.2006.06-0126. PMID 17407404.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Susan Watanabe (20 July 2001). "Mysteries of the Solar Nebula". NASA. Retrieved 2007-04-02.

- ^ Georgij A. Krasinsky, Elena V. Pitjeva, M. V. Vasilyev, E. I. Yagudina (2002). "Hidden Mass in the Asteroid Belt". Icarus. 158 (1): 98–105. doi:10.1006/icar.2002.6837.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Henry H. Hsieh, David Jewitt (23 March 2006). "A Population of Comets in the Main Asteroid Belt" (abstract page). Science. 312 (5773): 561–563. doi:10.1126/science.1125150. PMID 16556801. Retrieved 2008-04-05.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|number=and|issue=specified (help) - ^ Francis Reddy (2006). "New comet class in Earth's backyard". astronomy.com. Retrieved 2008-04-29.

- ^ A. Morbidelli, J. Chambers, J. I. Lunine, J. M. Petit, F. Robert, G. B. Valsecchi, K. E. Cyr (2000). "Source regions and timescales for the delivery of water to the Earth". Meteoritics & Planetary Science. 35: 1309. ISSN 1086–9379.

{{cite journal}}: Check|issn=value (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Florence Raulin-Cerceau, Marie-Christine Maurel, Jean Schneider (1998). "From Panspermia to Bioastronomy, the Evolution of the Hypothesis of Universal Life". Origins of Life and Evolution of Biospheres. 28. Springer Netherlands: 597–612. doi:10.1023/A:1006566518046. Retrieved 2007-12-19.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b G. Jeffrey Taylor (21 August 2001). "Uranus, Neptune, and the Mountains of the Moon". Planetary Science Research Discoveries. Hawaii Institute of Geophysics & Planetology. Retrieved 2008-02-01.

- ^ Alessandro Morbidelli (3 February 2008). "Origin and dynamical evolution of comets and their reservoirs" (PDF). arxiv. Retrieved 2007-05-26.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|year=/|date=mismatch (help) - ^ R. Malhotra (1995). "The Origin of Pluto's Orbit: Implications for the Solar System Beyond Neptune". Astronomical Journal. 110: 420. doi:10.1086/117532. arXiv:astro-ph/9504036.

- ^ M. J. Fogg, R. P. Nelson (2007). "On the formation of terrestrial planets in hot-Jupiter systems". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 461: 1195. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20066171. arXiv:astro-ph/0610314.

- ^ Kathryn Hansen (2005). "Orbital shuffle for early solar system". Geotimes. Retrieved 2006-06-22.

- ^ "Chronology of Planetary surfaces". NASA History Division. Retrieved 2008-03-13.

- ^ a b "UCLA scientists strengthen case for life more than 3.8 billion years ago" (Press release). University of California-Los Angeles. 21 July 2006. Retrieved 2008-04-29.

- ^ Clark R. Chapman (1996). "The Risk to Civilization From Extraterrestrial Objects and Implications of the Shoemaker-Levy 9 Comet Crash" (PDF). Abhandlungen der Geologischen Bundeanstalt, Wien,. 53: 51–54. ISSN 0016-7800. Retrieved 2008-05-06.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ a b Craig B. Agnor, Hamilton P. Douglas (2006). "Neptune's capture of its moon Triton in a binary-planet gravitational encounter" (PDF). Nature. 441 (7090): 192–194. doi:10.1038/nature04792. PMID 16688170.

- ^ a b Alessandro Morbidelli (2008-02-03). "Origin and dynamical evolution of comets and their reservoirs" (PDF). arxiv. Retrieved 2007-05-26.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|year=/|date=mismatch (help) - ^ Beth E. Clark, Robert E. Johnson (1996). "Interplanetary Weathering: Surface Erosion in Outer Space". Eos, Transactions, American Geophysical Union. 77: 141. doi:10.1029/96EO00094. Archived from the original on March 6, 2008. Retrieved 2008-03-13.

- ^ a b William F. Bottke, D. Durba, D. Nesvorny; et al. (2005). "The origin and evolution of stony meteorites" (PDF). Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union. Dynamics of Populations of Planetary Systems. Vol. 197. pp. 357–374. doi:10.1017/S1743921304008865.

{{cite conference}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ H. Alfvén, G. Arrhenius (1976). "The Small Bodies". SP–345 Evolution of the Solar System. NASA. Retrieved 2007-04-12.

- ^ N. Takato, S. J. Bus; et al. (2004). "Detection of a Deep 3-m Absorption Feature in the Spectrum of Amalthea (JV)". Science. 306 (5705): 2224. doi:10.1126/science.1105427. PMID 15618511.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)

See also Fraser Cain (24 December 2004). "Jovian Moon Was Probably Captured". Universe Today. Archived from the original on 2008-01-30. Retrieved 2008-04-03. - ^ D. C. Jewitt, S. Sheppard, C. Porco (2004). "Jupiter's outer satellites and Trojans" (PDF). In Fran Bagenal, Timothy E. Dowling, William B. McKinnon (eds.) (ed.). Jupiter. The Planet, Satellites and Magnetosphere. Cambridge University Press. pp. 263–280. ISBN 0-521-81808-7.

{{cite conference}}:|editor=has generic name (help); Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Scott S. Sheppard (Carnegie Institution of Washington). "The Giant Planet Satellite and Moon Page". Personal web page. Retrieved 2008-03-13.

- ^ Zeilik & Gregory (1998, pp. 118–120)

- ^ a b R. M. Canup, E. Asphaug (2001). "Origin of the Moon in a giant impact near the end of the Earth's formation". Nature. 412 (6848): 708. doi:10.1038/35089010. PMID 11507633.

- ^ D. J. Stevenson (1987). "Origin of the moon – The collision hypothesis". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 15: 271. doi:10.1146/annurev.ea.15.050187.001415.

- ^ G. Jeffrey Taylor (31 December 1998). "Origin of the Earth and Moon". Planetary Science Research Discoveries. Hawaii Institute of Geophysics & Planetology. Retrieved 2007-07-25.

- ^ Robin M. Canup (28 January 2005). "A Giant Impact Origin of Pluto-Charon" (abstract page). Science. 307 (5709): 546–550. doi:10.1126/science.1106818. PMID 15681378. Retrieved 2008-05-01.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|number=and|issue=specified (help) - ^ a b J. Laskar (1994). "Large-scale chaos in the solar system". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 287: L9 – L12.

- ^ Gerald Jay Sussman, Jack Wisdom (1988). "Numerical evidence that the motion of Pluto is chaotic" (PDF). Science. 241 (4864): 433–437. doi:10.1126/science.241.4864.433. PMID 17792606.

- ^ O. Neron de Surgy, J. Laskar (February 1997). "On the long term evolution of the spin of the Earth". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 318: 975–989. Retrieved 2008-06-08.

- ^ a b Wayne B. Hayes (2007). "Is the outer Solar System chaotic?". Nature Physics. 3: 689–691. doi:10.1038/nphys728. arXiv:astro-ph/0702179.

- ^ Ian Stewart (1997). Does God Play Dice? (2nd ed.). Penguin Books. pp. 246–249. ISBN 0-14-025602-4.

- ^ David Shiga (23 April 2008). "The solar system could go haywire before the sun dies". NewScientist.com News Service. Retrieved 2008-04-28.

- ^ C.D. Murray & S.F. Dermott (1999). Solar System Dynamics. Cambridge University Press. p. 184.

- ^ Dickinson, Terence (1993). From the Big Bang to Planet X. Camden East, Ontario: Camden House. pp. 79–81. ISBN 0-921820-71-2.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ A. Gailitis (1980). "Tidal Heating of Io and orbital evolution of the Jovian satellites". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 201: 415. Retrieved 2008-03-27.

- ^ R. Bevilacqua, O. Menchi, A. Milani; et al. (1980). "Resonances and close approaches. I. The Titan-Hyperion case". Earth, Moon, and Planets. 22 (2): 141–152. doi:10.1007/BF00898423. Retrieved 2007-08-27.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bruce G. Bills, Gregory A. Neumann, David E. Smith, and Maria T. Zuber (2006). "Improved estimate of tidal dissipation within Mars from MOLA observations of the shadow of Phobos". Journal of Geophysical Research. 110: E07004. doi:10.1029/2004JE002376.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ C. F. Chyba, D. G. Jankowski, P. D. Nicholson (1989). "Tidal evolution in the Neptune-Triton system". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 219: 23. Retrieved 2007-03-03.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ J. A. Burns, D. P. Simonelli, M. R. Showalter, D. P. Hamilton, C. C. Porco, L. W. Esposito, H. Throop (2004). "Jupiter's Ring-Moon System" (PDF). In Fran Bagenal, Timothy E. Dowling, William B. McKinnon (eds.) (ed.). Jupiter: The planet, Satellites and Magnetosphere. Cambridge University Press. p. 241. ISBN 0-521-81808-7. Retrieved 2008-05-14.

{{cite conference}}:|editor=has generic name (help); Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Martin J. Duncan, Jack J. Lissauer (1997). "Orbital Stability of the Uranian Satellite System". Icarus. 125 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1006/icar.1996.5568.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Marc Buie, William Grundy, Eliot Young, Leslie Young, Alan Stern (2006). "Orbits and Photometry of Pluto's Satellites: Charon, S/2005 P1, and S/2005". The Astronomical Journal. 132: 290. doi:10.1086/504422. arXiv:astro-ph/0512491.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stefano Coledan (2002). "Saturn Rings Still A Mystery". Popular Mechanics. Retrieved 2007-03-03.

- ^ "Saturn's recycled rings". Astronomy Now: 9. February 2008.

- ^ a b c Jeff Hecht (2 April 1994). "Science: Fiery future for planet Earth". New Scientist. No. 1919. p. 14. Retrieved 2007-10-29.

- ^ a b c d e f g h K. P. Schroder, Robert Connon Smith (2008). "Distant future of the Sun and Earth revisited". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 386: 155–163. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2008.13022.x.

- ^ Knut Jørgen, Røed Ødegaard (2004). "Our changing solar system". Centre for International Climate and Environmental Research. Retrieved 2008-03-27.

- ^ a b Jeffrey Stuart Kargel (2004). Mars: A Warmer, Wetter Planet. Springer. ISBN 1852335688. Retrieved 2007-10-29.

- ^ Zeilik & Gregory (1998, p. 320–321)

- ^ "Introduction to Cataclysmic Variables (CVs)". NASA Goddard Space Center. 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-29.

- ^ a b c d I. J. Sackmann, A. I. Boothroyd, K. E. Kraemer (1993). "Our Sun. III. Present and Future". Astrophysical Journal. 418: 457. doi:10.1086/173407.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zeilik & Gregory (1998, p. 322)

- ^ a b Ralph D. Lorenz, Jonathan I. Lunine, Christopher P. McKay (1997). "Titan under a red giant sun: A new kind of "habitable" moon" (PDF). Geophysical Research Letters. 24 (22): 2905. doi:10.1029/97GL52843. PMID 11542268. Retrieved 2008-03-21.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Marc Delehanty. "Sun, the solar system's only star". Astronomy Today. Retrieved 2006-06-23.

- ^ K. R. Rybicki, C. Denis (2001). "On the Final Destiny of the Earth and the Solar System". Icarus. 151 (1): 130–137. doi:10.1006/icar.2001.6591.

- ^ a b Bruce Balick (Department of Astronomy, University of Washington). "Planetary nebulae and the future of the Solar System". Personal web site. Retrieved 2006-06-23.

- ^ B. T. Gänsicke, T. R. Marsh, J. Southworth, A. Rebassa-Mansergas (2006). "A Gaseous Metal Disk Around a White Dwarf". Science. 314 (5807): 1908–1910. doi:10.1126/science.1135033. PMID 17185598.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|number=and|issue=specified (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Richard W. Pogge (1997). "The Once & Future Sun" (lecture notes). New Vistas in Astronomy. Retrieved 2005-12-07.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^ T. S. Metcalfe, M. H. Montgomery, A. Kanaan (2004). "Testing White Dwarf Crystallization Theory with Asteroseismology of the Massive Pulsating DA Star BPM 37093". Astrophysical Journal. 605: L133. doi:10.1086/420884. arXiv:astro-ph/0402046.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b G. Fontaine, P. Brassard, P. Bergeron (2001). "The Potential of White Dwarf Cosmochronology". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 113: 409–435. doi:10.1086/319535. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stacy Leong (2002). Glenn Elert (ed.) (ed.). "Period of the Sun's Orbit around the Galaxy (Cosmic Year)". The Physics Factbook (self-published). Retrieved 2008-06-26.

{{cite web}}:|editor=has generic name (help); External link in|work= - ^ Michael Szpir. "Perturbing the Oort Cloud". American Scientist. The Scientific Research Society. Retrieved 2008-03-25.

- ^ Erik M. Leitch, Gautam Vasisht (1998). "Mass Extinctions and The Sun's Encounters with Spiral Arms". New Astronomy. 3: 51–56. doi:10.1016/S1384-1076(97)00044-4. Retrieved 2008-04-09.

- ^ a b c d e Fraser Cain (2007). "When Our Galaxy Smashes Into Andromeda, What Happens to the Sun?". Universe Today. Retrieved 2007-05-16.

- ^ a b J. T. Cox, Abraham Loeb (2007). "The Collision Between The Milky Way And Andromeda". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 386: 461. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2008.13048.x. arXiv:0705.1170. Retrieved 2008-04-02.

- ^ J. Braine, U. Lisenfeld, P. A. Duc, E. Brinks, V. Charmandaris, S. Leon (2004). "Colliding molecular clouds in head-on galaxy collisions". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 418: 419–428. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20035732. Retrieved 2008-04-02.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Simon A. Wilde, John W. Valley, William H. Peck, Colin M. Graham (2001). "Evidence from detrital zircons for the existence of continental crust and oceans on the Earth 4.4 Gyr ago" (PDF). Nature. 409 (6817): 175. doi:10.1038/35051550. PMID 11196637.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gary Ernst Wallace (2000). "Earth's Place in the Solar System". Earth Systems: Processes and Issues. Cambridge University Press. pp. 45–58. ISBN 0521478952.

- ^ Barrow, John D.; Tipler, Frank J. (1986). The Anthropic Cosmological Principle (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-282147-8. LCCN 87028148.

Bibliography

- Michael A. Zeilik, Stephen A. Gregory (1998). Introductory Astronomy & Astrophysics (4th ed.). Saunders College Publishing. ISBN 0030062284.

External links

- 7M animation from skyandtelescope.com showing the early evolution of the outer Solar System.

- Quicktime animation of the future collision between the Milky Way and Andromeda

- How the Sun Will Die: And What Happens to Earth (Video at Space.com)

Template:Link GA Template:Link GA Template:Link GA Template:Link GA