Lake Nipigon

| Lake Nipigon | |

|---|---|

View of the lake from Orient Bay | |

| Location | Ontario |

| Coordinates | 49°50′N 88°30′W / 49.833°N 88.500°W |

| Lake type | Glacial |

| Primary inflows | Gull, Wabinosh, Whitesand, Little Jackfish, Ombabika, Onaman, Namewaminikan Rivers |

| Primary outflows | Nipigon River |

| Catchment area | 24,560 km2 (9,484 sq mi)[1] |

| Basin countries | Canada |

| Surface area | 4,848 km2 (1,872 sq mi) |

| Average depth | 54.9 m (180 ft)[2] |

| Max. depth | 165 m (541 ft) |

| Water volume | 266 km3 (64 cu mi; 216×106 acre⋅ft)[2] |

| Shore length1 | 1,044 km (649 mi)[2] |

| Surface elevation | 260 m (850 ft) |

| Islands | Caribou Island, Geikie Island, Katatota Island, Kelvin Island, Logan Island, Murchison Island, Murray Island, and Shakespeare Island |

| 1 Shore length is not a well-defined measure. | |

Lake Nipigon (/ˈnɪpɪɡɒn/ NIP-ih-gon; French: lac Nipigon; Ojibwe: Animbiigoo-zaaga'igan) is part of the Great Lakes drainage basin. It is the largest lake entirely within the boundaries of the Canadian province of Ontario.

Etymology

[edit]In the Jesuit Relations the lake is called lac Alimibeg, and was subsequently known as Alemipigon or Alepigon. In the 19th century it was frequently spelled as Lake Nepigon. This may have originated from the Ojibwe word Animbiigoong, meaning 'at continuous water' or 'at waters that extend [over the horizon].' Though some sources claim the name may also be translated as 'deep, clear water,' this description is for Lake Temagami. Today, the Ojibwa bands call Lake Nipigon Animbiigoo-zaaga'igan.

The 1778 Il Paese de' Selvaggi Outauacesi, e Kilistinesi Intorno al Lago Superiore map by John Mitchell identifies the lake as Lago Nepigon and its outlet as F. Nempissaki. In the 1807 map A New Map of Upper & Lower Canada by John Cary, the lake was called Lake St. Ann or Winnimpig, while the outflowing river as Red Stone R. Today, the Red Rock First Nation located along the Nipigon River still bears the "Red Stone" name. In the 1827 map Partie de la Nouvelle Bretagne. by Philippe Vandermaelen, the lake was called L. St. Anne, while the outflowing river as R. Nipigeon. In the 1832 map North America sheet IV. Lake Superior. by the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, the lake was called St Ann or Red L., while the outflowing river as Neepigeon and the heights near the outlet of the Gull River as Neepigon Ho. By 1883, maps such as Statistical & General Map of Canada by Letts, Son & Co., consistently began identify the lake as Lake Nipigon.

Geography

[edit]

Lying 260 metres (853 ft) above sea level, the lake drains into the Nipigon River and thence into Nipigon Bay of Lake Superior. The lake and river are the largest tributaries of Lake Superior. It lies about 120 kilometres (75 mi) northeast of the city of Thunder Bay, Ontario.[3]

Lake Nipigon has a total area (including islands within the lake) of 4,848 square kilometres (1,872 sq mi), compared to 3,150 square kilometres (1,220 sq mi) for Lake of the Woods. It is the 32nd largest lake in the world by area. The largest islands are Caribou Island, Geikie Island, Katatota Island, Kelvin Island, Logan Island, Murchison Island, Murray Island, and Shakespeare Island. Maximum depth is 165 metres (541 ft).

Its original watershed area is 24,560 km2 (9,484 sq mi). This was increased by about 60% to 38,920 square kilometres (15,030 sq mi) after 14,360 square kilometres (5,545 sq mi) of the Ogoki River basin were diverted in 1943 to the headwaters of the Little Jackfish River, a tributary of Lake Nipigon.[1]

Geology

[edit]

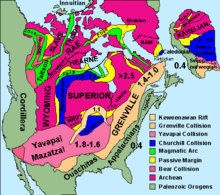

Lake Nipigon occupies a basin created by repeated and preferential erosion of relatively flat-lying and faulted, Proterozoic sedimentary strata and igneous sills by repeated Pleistocene glaciations. The Sibley Group consists of about 950 metres (3,120 ft) of unmetamorphosed Mesoproterozoic red beds that are typically flat-lying. These red beds consist of basal fluvial-lacustrine conglomerates, sandstones, and shales overlain by cyclic dolomite-siltstone layers, stromatolites and red mudstones, which represent a playa lake, sabkha, and mudflat environments; purple shales and siltstones interpreted as subaerial mudflat deposits; and an upper unit of cross-stratified sandstone beds, which are interpreted to be aeolian in origin. They accumulated in an intracratonic rift basin between 1450 and 1500 million years (Ma) ago.[4][5]

The Sibley Group unconformably overlies highly deformed and metamorphosed Archean turbiditic sandstones and metavolcanic and granitic rocks. The strata of the Sibley Group fill and are limited to a rift basin known as the Nipigon Embayment that underlies Lake Nipigon. Outside of the rift basin and east and west of Lake Nipigon, the Sibley Group is absent and erosion resistant Archean rocks are either exposed at the surface or blanketed by Pleistocene glacial sediments.[4][5][6]

The Archean and Proterozoic strata are intruded by a number of mafic and ultramafic intrusions, which define the current outline of the Nipigon Embayment. They consist of relatively flat-lying and undeformed diabase sills known as the Nipigon diabase sills. These sills range in thickness from a few meters to 150 metres (490 ft) thick in cliff sections to more than 250 metres (820 ft) thick in drill core. They are estimated to cover an area in excess of 20,000 square kilometres (7,700 sq mi). The Nipigon diabase sills give evidence of rift-related continental basaltic magmatism during the Midcontinent Rift System event, estimated at 1,109 Ma ago. Thick sills up to 150 to 200 metres (490–660 ft) thick are also related with the rifting event, forming cliffs that are up to 150 to 200 metres (490–660 ft) high. The mafic and ultramafic intrusions in and around the Nipigon Embayment have widely been interpreted to represent a failed arm of the Midcontinent Rift System, although the lack of dike intrusions, compared to the relative abundance of flat, saucer-shaped sills in the embayment, has led some researchers to question the dominant failed rift arm model.[6][7][8]

The Proterozoic rocks that underlie the Lake Nipigon region contain a variety of mineral resources. Although economic deposits have yet to be found, 1.53 billion-year-old anorogenic granites within the Lake Nipigon area potentially contain yttrium, zirconium, rare earth elements and tin mineralization. The clastic sedimentary rocks of the Sibley Group, are host to unconformity-related uranium and redbed-type copper ore deposits.[7][9]

History

[edit]As the last ice age was ending, Lake Nipigon was, at times, part of the drainage path for Lake Agassiz.[10]

French Era (Fort la Tourette)

[edit]The French Jesuit Claude Allouez celebrated the first Mass beside the Nipigon River May 29, 1667.[11][12] He visited the village of the Nipissing Indians who had fled there during the Iroquois onslaught of 1649-50.

In 1683, Daniel Greysolon, Sieur du Lhut, established a fur trading post on Lake Nipigon named Fort la Tourette after his brother, Claude Greysolon, Sieur de la Tourette. The Alexis Hubert Jaillot map of 1685 (Partie de la Nouvelle-France)[13] suggests that this fort was somewhere in Ombabika Bay at the northeast end of the lake where the Ombabika River and Little Jackfish River (Kabasakkandagaming) empty. This post, like most of the western French posts, was closed in 1696 by order of the king, when, due to a surplus of beaver pelts, the system of trading permits established in 1681 was abolished.[14]

On 17 April 1744, the Count of Maurepas, Minister of the Marine, informed the Canadian officials that Jean de La Porte was to be given the "fur ferme" (i.e. the profits) of Lac Alemipigon from that year forward as a reward for his services in New France.

Mid 18th and 19th century: British Era

[edit]After the Treaty of Paris (1763), the area passed into the hands of the British, and the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) expanded its trading area to include the Lake, to compete with the North West Company, who were already operating there. In 1784 and 1790, the HBC sent representatives to survey the lake, and set up their first trading post in 1792 on the north-east side. Around 1821, the HBC replaced the original post with a second one in the northwest, called Wabinosh House. It was nearly abandoned due to strife and murders between local indigenous groups. Once the dispute was resolved however, the post remained open.[15]

Although it was considered to be within British North America, it was not until 1850 that the watershed draining into Lake Superior was ceded formally by the Ojibwe Indians to the Province of Canada in the Robinson Treaty of 1850, also known as the Robinson Superior Treaty. A four square mile reservation was set aside on Gull River near Lake Nipigon on both sides of the river for the Chief Mishe-muckqua (from Mishi-makwa, "Great Bear"). That same year, the HBC moved its trading post there from Wabinosh Bay. The post, known as Nipigon or Fort Nipigon, was headquarters of the Nipigon District from 1881 to 1892. In 1900, the post was renamed to Nipigon House, and renamed again in 1954 to Gull Bay.[15]

In 1871 Lake Nipigon was included in the new Thunder Bay District.

20th Century

[edit]The Township of Nipigon was incorporated in 1908. The Municipality of Greenstone (pop 5662) was incorporated in 2001 and includes Orient Bay, MacDiarmid, Beardmore, Nakina, Longlac, Caramat, Jellicoe and Geraldton.

In 1943 Canada and the United States agreed to the Ogoki diversion which diverts water into Lake Superior that would normally flow into James Bay and thence into Hudson Bay. The diversion connects the upper portion of the Ogoki River to Lake Nipigon. This water was diverted to boost the Sir Adam Beck Hydroelectric Generating Stations at Niagara Falls.[16] The diversion is governed by the International Lake Superior Board of Control which was established in 1914 by the International Joint Commission.

First Nations

[edit]The aboriginal population (primarily Ojibwe) include the Animbiigoo Zaagi'igan Anishinaabek (Lake Nipigon Ojibway) First Nation, the Biinjitiwaabik Zaaging (Rocky Bay whose name changed in 1961 from McIntyre Bay Indian Band) Anishinaabek First Nation, the Bingwi Neyaashi (Sand Point) Anishinaabek First Nation, the Red Rock (Lake Helen) First Nation and the Gull Bay First Nation. Formerly, the Whitesand First Nation was also located along the northwestern shores of Lake Nipigon until they were relocated in 1942. The membership of these six First Nations total about 5,000. Additionally along Lake Nipigon, there are three Indian reserves : McIntyre Bay IR 54 (Rocky Bay First Nation), Jackfish Island IR 57 and Red Rock (Parmachene) IR 53 (Red Rock First Nation).

The first nations CBC TV series Spirit Bay was filmed on the lake at the Biinjitiwaabik Zaaging Anishinaabek First Nation Reserve in the mid-1980s.

Transportation

[edit]The main line of the Canadian National Railway runs to the north of the lake. Another branch of the CNR touches the southeastern section of the lake at Orient Bay and Macdiarmid before heading inland to Beardmore. Ontario Highway 11 also skirts the southeastern section of the lake.[17]

Water travel between Lake Nipigon and Lake Superior is impossible because of the existence of three dams that effectively hinders navigation.

Protected areas

[edit]Ontario Parks has designated the area as the Lake Nipigon Basin Signature Site, because of its remarkable range of natural and recreational values. The site includes many provincial parks, conservation reserves, and enhanced management areas around the lake and within its watershed.[18]

Protected areas on or at Lake Nipigon include:

- Lake Nipigon Provincial Park - located on the east side of Lake Nipigon. In 1999 the park boundary was amended to reduce the park area from 14.58 to 9.18 km2 (5.63 to 3.54 sq mi). The area removed from the park was deregulated and transferred to the Government of Canada for a reserve for the Sand Point First Nation.

- Lake Nipigon Conservation Reserve - 176,660 ha (436,500 acres) reserve, created in 2003, that includes all Crown islands and most of the shoreline of Lake Nipigon.[19]

- Black Sturgeon River Provincial Park - includes the southern-most end of Black Sturgeon Bay of Lake Nipigon.[20]

- Kabitotikwia River Provincial Park - 1,965 ha (4,860 acres) nature reserve at Gull Bay, created in 1985, protecting the wetlands at the mouth of the Kabitotikwia River.[21]

- Kopka River Provincial Park - includes the entire shore of and the islands in Wabinosh Bay, on the lake's western shore.[22]

- Livingstone Point Provincial Park - 1,800 ha (4,400 acres) nature reserve, created in 1985, protecting regionally rare arctic and alpine plants on a peninsula off the lake's eastern shore.[23]

- West Bay Provincial Park - 1,120 ha (2,800 acres) nature reserve, created in 1985, protecting geological features on the north shore of the namesake bay.[24]

- Windigo Bay Provincial Park - 8,378 ha (20,700 acres) nature reserve, created in 1989, protecting a migration corridor and wintering sites for woodland caribou on the north shore of the lake, west of the namesake bay.[25]

Other protected areas within the lake's basin:

- Garden Pakashkan Conservation Reserve - includes the Mooseland River (a tributary of the Gull River), its headwaters, Garden Lake, and Mooseland Lake. The 12,586 ha (31,100 acres) reserve, established in 2004, protects extremely rugged terrain and canyons in a remote area.[26]

- Gull River Provincial Park - protecting the Gull River, a tributary to Lake Nipigon.

- Obonga-Ottertooth Provincial Park - 21,157 ha (52,280 acres) waterway park that includes a system of lakes and rivers from Obonga Lake in the east to Kashishibog Lake in the west.[27]

- Kaiashk Provincial Park - 780 ha (1,900 acres) nature reserve, established in 1989, protecting post-glacial features such as a kame knoll, outwash plain, and troughs.[28]

- Nipigon Palisades Conservation Reserve - 11,588.8 ha (28,637 acres) reserve, established in 2003, protecting a prominent geological canyon/ravine and tablelands. It also includes a major moose migration corridor (Cash Creek).[29]

- Ottertooth Conservation Reserve - 28,793 ha (71,150 acres) reserve, established in 2003, protecting provincially-significant and unique geological features related to a spillway of glacial Lake Agassiz.[30]

- Pantagruel Creek Provincial Park - 2,685 ha (6,630 acres) nature reserve, established in 1989, protecting Pantagruel Creek that formed part of the spillway of glacial Lake Agassiz.[31]

- Whitesand Provincial Park - 11,337 ha (28,010 acres) waterway park, established in 2003, includes a system of lakes and rivers that links Wabakimi Provincial Park, Windigo Bay Provincial Park, and Lake Nipigon.[32]

References

[edit]- ^ a b United States Great Lakes Basin Commission (1976). Great Lakes Basin Commission Framework Study. Vol. 11–14. Public Information Office, Great Lakes Basin Commission. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ a b c "Lake Nipigon". World Lake Database. International Lake Environment Committee Foundation (ILEC). Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ^ "Lake Nipigon Region Geoscience Initiative". Archived from the original on 2012-07-24. Retrieved 2012-05-21.

- ^ a b Rogala, B., 2003. The Sibley Group: a lithostratigraphic, geochemical and paleomagnetic study. Unpublished MSc thesis, Lakehead University, Thunder Bay, Ontario, Canada, 254 pp.

- ^ a b Rogala, B., Fralick, P.W., Heaman, L.M. and Metsaranta, R., 2007. Lithostratigraphy and chemostratigraphy of the Mesoproterozoic Sibley Group, northwestern Ontario, Canada. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 44, pp. 1131–1149.

- ^ a b Hart, T.R. and MacDonald, C.A., 2007. Proterozoic and Archean geology of the Nipigon Embayment: implications for emplacement of the Mesoproterozoic Nipigon diabase sills and mafic to ultramafic intrusions. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 44(8), pp.1021-1040.

- ^ a b Sutcliffe, R.H., 1991. Proterozoic Geology of the Lake Superior Area, In P.C. Thurston, H.R. Williams, R.H. Sutcliffe, and G.M. Stott (eds.). Geology of Ontario, Ontario Geological Survey, Special Publication 4 (1), pp. 627-658.

- ^ Davis, D.W. and Sutcliffe, R.H., 1985. U-Pb ages from the Nipigon plate and northern Lake Superior. Geological Society of America Bulletin, 96(12), pp.1572-1579.

- ^ Thurston, P.C., Williams, H.R., Sutcliffe, R.H. and Stott, G.M., 1991. Geology of Ontario. Ontario Geological Survey Special Publication, 4(Part 1), 711 p

- ^ Leverington, DW; Teller JT (2003). "Paleotopographic reconstructions of the eastern outlets of glacial Lake Agassiz". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 40 (9): 1259–78. Bibcode:2003CaJES..40.1259L. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.468.8518. doi:10.1139/e03-043.

- ^ "Mission to the Nipissings 1667". Read the Plaque. Retrieved 2021-07-07.

- ^ "The Visit of Father Allouez to Lake Nipigon in 1667" (PDF). cchahistory. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- ^ Partie de la Nouvelle France "Partie de la Nouvelle France (Hubert Jaillot 1685) | Flickr". 12 December 2007. Archived from the original on 2017-01-20. Retrieved 2017-01-19.; also, "Partie de la Nouvelle France / Par Hubert Jaillot". Archived from the original on 2012-04-21. Retrieved 2012-04-19.

- ^ Nive Voisine, «Robutel de la Noue, Zacharie» Dictionnaire de biographie canadienne, v. 2 (1701-1740); Gratien Allaire, «Les engagements pour la traite des fourrures : évaluation de la documentation,» Revue d'histoire de l'Amérique française, 34 (juin 1980), 9-10.

- ^ a b "Hudson's Bay Company: Nipigon House". pam.minisisinc.com. Archives of Manitoba - Keystone Archives Descriptive Database. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ Annin, Peter (2009). The Great Lakes water wars (1st Island Press pbk. ed.). Washington: Island Press. ISBN 9781597266376. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ "CN - Transportation Services - Rail Shipping, Intermodal, trucking, warehousing and international transportation". www.cn.ca. Archived from the original on 22 April 2018. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- ^ "Lake Nipigon Basin Signature Site Park Management Parent Plan for Lake Nipigon, Kabitotikwia River, Livingstone Point, West Bay and Windigo Bay provincial parks". Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. 2003. Retrieved 1 March 2024.

- ^ "Policy Report C2247: LAKE NIPIGON CONSERVATION RESERVE". Crown Land Use Policy Atlas. Ministry of Natural Resources Ontario. 10 July 2006. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ "Black Sturgeon River Provincial Park". www.ontarioparks.com. Ontario Parks. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ "Kabitotikwia River Provincial Park". www.ontarioparks.com. Ontario Parks. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ "Kopka River Provincial Park". www.ontarioparks.com. Ontario Parks. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ "Livingstone Point Provincial Park". www.ontarioparks.com. Ontario Parks. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ "West Bay Provincial Park". www.ontarioparks.com. Ontario Parks. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ "Windigo Bay Provincial Park". www.ontarioparks.com. Ontario Parks. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ "Policy Report C2410: Garden Pakashkan Conservation Reserve". Crown Land Use Policy Atlas. Ministry of Natural Resources Ontario. 31 January 2006. Retrieved 4 March 2024.

- ^ "Obonga-Ottertooth Provincial Park". www.ontarioparks.com. Ontario Parks. Retrieved 4 March 2024.

- ^ "Kaiashk Provincial Park". www.ontarioparks.com. Ontario Parks. Retrieved 4 March 2024.

- ^ "Policy Report C2238: Nipigon Palisades Conservation Reserve". Crown Land Use Policy Atlas. Ministry of Natural Resources Ontario. 2 March 2009. Retrieved 4 March 2024.

- ^ "Policy Report C2262: Ottertooth Conservation Reserve". Crown Land Use Policy Atlas. Ministry of Natural Resources Ontario. 31 January 2006. Retrieved 4 March 2024.

- ^ "Pantagruel Creek Provincial Park". www.ontarioparks.com. Ontario Parks. Retrieved 4 March 2024.

- ^ "Whitesand Provincial Park". www.ontarioparks.com. Ontario Parks. Retrieved 4 March 2024.