Franco-Dutch War

| Franco–Dutch War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Painting of the capture of Coevorden by Dutch troops commanded by Carl von Rabenhaupt in December 1672 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

| Unknown | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

| 100,000 casualties[2] | ||||||||

| 175,000 dead[2] | |||||||||

The Franco-Dutch War (1672–78), often simply called the Dutch War (Template:Lang-fr; Template:Lang-nl), was a war fought by France, Sweden, Münster, Cologne and England against the Dutch Republic, which was later joined by the Austrian Habsburg lands, Brandenburg-Prussia and Spain to form a Quadruple Alliance. The war ended with the Treaty of Nijmegen, by which Spain ceded the Franche-Comté and some cities in Flanders and Hainaut to France, while France returned some of its conquests (Maastricht and the Principality of Orange) to the Dutch.

The year 1672, when a full invasion of English, French and German forces took much of the Dutch Republic by surprise, is often referred to as het Rampjaar ("the Disaster Year") in Dutch.[3]

Origins

In order to weaken its Hapsburg rivals in Spain and the Holy Roman Empire, largely Catholic France supported the Dutch Republic during the 1568-1648 Eighty Years War and in 1635, it entered the Thirty Years' War as part of the anti-Imperial Protestant alliance.[4] These ended with the 1648 Peace of Westphalia but the subsidiary Franco-Spanish War continued until the 1659 Treaty of the Pyrenees; this ended Spanish pre-eminence in Europe, while France emerged substantially stronger. During the 1667-1668 War of Devolution, France captured most of the Spanish Netherlands but under the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, it was forced to relinquish most of these gains by the Triple Alliance between the Dutch, England and Sweden.[5]

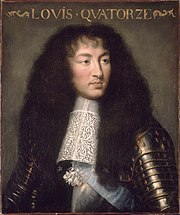

Louis XIV recognised the need to break up the Alliance before making another attempt on the Spanish Netherlands.[6] This was made easier by the ongoing commercial rivalry between England and the Dutch Republic, which caused the Anglo-Dutch Wars of 1652-1654 and 1665-1667.[7] In the 1670 Treaty of Dover signed by Charles II of England and Louis XIV, England agreed to an alliance against the Dutch Republic and to supply a Brigade of 6,000 troops for the French army.[8] The Treaty also contained secret provisions, which were not revealed until 1771; these included Charles' agreement to become a Catholic plus subsidies of £230,000 per year for the services of this Brigade.[9] Sweden, the third member of the Triple Alliance, indirectly supported France by agreeing to attack Brandenburg-Prussia if it attempted to intervene.

Preparations

Measures taken by Louvois, Louis' Secretary of War, allowed France to mobilise about 180,000 men. Of these about 120,000 would be used directly against the Republic. The bulk of the French army was divided into two bodies. The body led by field marshal Turenne was stationed in Charleroi, then France. The body led by Condé waited in Sedan.[10] Both would march through the pro-France Prince-Bishopric of Liège, join near Maastricht and gain the Rhine.

On the Rhine, a third body would be waiting. It had been created from the allied armies of Münster and Cologne and was placed under the command of Luxembourg. The combined armies would then attack the duchy of Cleves and the region of Nijmegen.[10] A fourth body was to be an English expeditionary force, but the English landings did not take place (see Third Anglo-Dutch War). The alliances clashed when England declared war on the Republic, on 7 April 1672.

The French Offensive; 1672-1674

The French offensive began after Louis arrived in Charleroi on 5 May 1672; avoiding a direct assault on Maastricht, they occupied the forts of Tongeren, Maaseik and Valkenburg, keeping its garrison bottled up.[10] On 11 May, Turenne's army of 50,000 advanced along the Rhine, supported by forces from Münster and the Electorate of Cologne. They captured Rheinberg, Wesel, Burick and Orsoy and by the middle of July, the major Dutch fortresses of Nijmegen and Fort Crèvecœur near 's-Hertogenbosch had also fallen.[11]

These losses initially caused panic and a divided States General asked Louis for peace terms. On 7 June, Dutch Admiral Michiel de Ruyter boldly attacked an Anglo-French fleet assembling off the English coast at Southwold; the Battle of Solebay was a tactical draw but a strategic Dutch victory, as it prevented an attempted Anglo-French blockade.[11]

The negotiations with France provided time to finish the Dutch Water Line; after the army of William of Orange withdrew behind them, the gates were opened on 22 June 1672, flooding the land. When French terms were received on 1 July, they caused outrage; in addition to their existing gains, the Dutch were given the choice of surrendering their southern fortresses, religious freedom for Catholics and a payment of six million guilders, or a single payment of sixteen million guilders.[12]

These events bolstered Dutch resistance and on 4 July, William was appointed Stadtholder. At Groningen in July, the Dutch repelled an invasion force from Münster, then recaptured most of the territory lost in June.[13]. In August, Johan and Cornelis de Witt, whose policies were blamed for the Dutch collapse, were lynched by an Orangist mob, leaving William in control.[14]

The Dutch position had stabilised, while concern at French gains brought support from Frederick William of Brandenburg-Prussia, Emperor Leopold and Charles II of Spain.[7] Instead of a rapid victory, Louis was forced into another war of attrition around the French frontiers; in August, Turenne ended his offensive against the Dutch and proceeded to Germany with 25,000 infantry and 18,000 cavalry.[15] Frederick William and Leopold combined their forces of around 25,000 under the Imperial general Raimondo Montecuccoli; he crossed the Rhine at Koblenz in January 1673 but Turenne forced him to retreat into northern Germany.[16]

Until the advent of railways in the 19th century, goods and supplies were largely transported by water, making rivers such as the Lys, Sambre and Meuse vital for trade and military operations.[17] In 1673, the primary French objective in Flanders was the Dutch fortress of Maastricht, which controlled a key access point on the Meuse.[18] As agreed by the Treaty of Dover, the French army of 45,000 included the Anglo-Scots Brigade, commanded by the Duke of Monmouth, Charles' illegitimate son.[19] Monmouth's troops included John Churchill, later Duke of Marlborough and John Graham, future Viscount Dundee.[20]

At Maastricht, Louis introduced an important innovation; in the past, engineers simply provided technical advice but he now put Vauban in charge of siege operations and despite repulsing several assaults, the city surrendered on 30 June.[21] French casualties included Charles d'Artagnan, while Churchill was wounded during an attack on the night of 27 June 1673.[22]

In June 1673, the French occupation of Kleve and lack of money temporarily drove Brandenburg-Prussia out of the war in the Peace of Vossem.[23] However, in August, the Dutch, Spain and Austria, supported by other German states, agreed the anti-French Alliance of the Hague, joined by Charles IV of Lorraine in October.[24]

Turenne was tasked with protecting French gains in the Rhineland, while preventing Montecuccoli combining with William but had insufficient strength to do both.[25] William recaptured Naarden in September; with the war expanding into the Rhineland and Spain, the French withdrew from the Dutch Republic in October, while Münster and Cologne left the war after the loss of Bonn in November.[26]

The alliance between England and Catholic France was unpopular from the start and although the real terms of the Treaty of Dover remained secret, many suspected them.[27] The Cabal ministry that managed government for Charles gambled on a short war but after the failure of the French offensive, opinion quickly turned against it. The Dutch published details of Louis' peace terms that effectively ignored the Treaty of Dover, while the French were accused of abandoning the English at Solebay.[28]

Discontent increased when Charles' heir, his Catholic brother James, was given permission to marry Mary of Modena, also a devout Catholic.[29] In February 1673, Parliament refused to fund the war unless Charles withdrew a proposed Declaration of Indulgence and accept a Test Act barring Catholics from public office.[30] After the Dutch defeated an Anglo-French fleet in August at Texel, the pressure to end the war became unstoppable.[31] In the February 1674 Treaty of Westminster, England signed a separate peace with the Dutch.[32]

In the Americas, Dutch naval forces captured the English settlement of New York City in 1673 and Port-Royal, capital of the French colony of Acadia in 1674. New York was returned to England after the Treaty of Westminster, while their claim to Acadia was simply abandoned.

The War Expands; 1674-1678

During the winter of 1673–1674, Turenne based his troops in Alsace and the Palatinate; the costs of quartering his army through the winter was so unpopular that the Electoral Palatinate later joined the Imperial forces.[33] He began his campaign on 12 June 1674 with 6,000 cavalry, 2,000 infantry and 6 cannons; despite England's withdrawal, this contained a number of English regiments. Under the Treaty of Dover, Charles received £230,000 per year for the Anglo-Scots Brigade and in order to keep his subsidies, members of the Brigade were encouraged to remain in French service; Monmouth and Churchill were among those who did so, but others enrolled in the Dutch Scots Brigade, including John Graham, later Viscount Dundee.[34]

Turenne marched on Philippsburg, crossing the Rhine on 14 June 1674, hoping to attack forces under Enea Caprara and Duke Charles IV before they could be reinforced by Alexander von Bournonville's Imperial army. On 16 June 1674, Turenne defeated an Imperial army at the Battle of Sinsheim but this delayed him long enough for Bournonville to join forces with Caprara and Charles at Heidelberg.[35]

Turenne arrived at Heidelberg but crossed to the western bank of the Rhine bank, where he received reinforcements near Neustadt. As he prepared to cross the Neckar river, memories of their defeat at Sinsheim led the Imperial troops on the other side to flee, exposing the Palatinate to the French.[36]

Bournonville marched south and captured Strasbourg, providing a base to attack Alsace but before doing so, he awaited the arrival of 20,000 troops under Frederick William. Determined to defeat him before this, Turenne made a night march on 2–3 October 1674, arriving at Molsheim where he left his army's baggage and advanced against Bournonville on 4 October.[37] At Entzheim, the Imperial army was taken by surprise and comprehensively defeated after Turenne's right wing under the Marquis de Boufflers captured a key position on the Imperial left; Boufflers' troops included three regiments led by Churchill.[38]

Also in 1674, there was fighting along the Pyrenees, as Frederick von Schomberg led a small French army against the Spanish in Roussillon.[39] Even with the 10,000 local militia troops that Louis added to Schomberg's army, Schomberg felt himself disadvantaged against the Spanish. The Spanish forces under the command of General San Germán took Fort Bellegarde on the spine of the Pyrenees. On 19 June 1674, the French suffered another defeat at Maureillas.[39] Things went somewhat better for the French after a revolt by the citizens of Messina, Sicily, against their Spanish overlords about an increase in taxes, required San Germán to hold back a number of his troops to be ready for shipment to Sicily.[39] In 1675, Schomberg was able to retake Fort Bellegarde.

By the end of 1675, even those English troops that had been serving in the French armies as mercenaries were being called home. By December 1675, Marlborough and all his troops were in Paris on their way home.[40] Also in 1675, the Great Condé was becoming so incapacitated with gout and other infirmities that he was unable to carry out all his duties without help. Consequently, Louis was required to raise a new army with a new general. Accordingly, between 5,000–6,000 men were raised and placed under the command of Marshal François-Joseph, marquis of Créqui.[41] In early December 1674, Turenne prepared to go out on this winter campaign. On 29 December 1674, he surprised and smashed the Imperial cavalry at Mulhouse.[42] Then, Turenne marched for Colmar where he expected to meet the army of Frederick William, who had managed to gather 30,000 to 40,000 of his men out of winter quarters and take up a defence line between Colmar and Turkheim. However, the latter army still had not gelled in place on 5 January 1674, when Turenne attacked with 30,000 French troops.[43] Turenne feigned an attack to the right and then to the center, while hidden by the terrain, some of his infantry moved around to the left and took the town of Turkheim on Frederick William's flank.[39] An attempt to retake Turkheim was defeated under heavy fire from the French and an infantry charge. Frederick William retreated back to Strasbourg and crossed over to the eastern Rhine bank.[39]

The Spanish wanted to cut the French supply route. They therefore had been attempting to retake Maastricht ever since its fall. The Prince-Bishopric of Liège refusing to join the anti-French coalition, the Spanish tried to support an anti-French uprising (January 1674) and took military control of the cities of Huy and Dinant.[44] Finally on 31 March 1675, just when an anti-French uprising seemed most imminent, Maastricht sent a garrison of 1,500 soldiers to the city of Liège.[45] From France, a fresh army marched in and retook Dinant (21–29 May 1675) and Huy (31 May–6 June 1675).[46] Likewise the town of Limbourg was taken by the French after a siege lasting from 13 June until 21 June 1675.[47] Meanwhile, Turenne was trying to protect the Alsace from invasion by Montecuccoli. On 27 July 1675, Turenne caught Montecuccoli's army (Battle of Salzbach). However, during an Imperial artillery barrage, a cannonball landed among a group of French officers and killed Turenne.[48] Though defeated in this battle, Montecuccoli and his imperial forces were victorious in the following campaign, driving the French back to the Vosges mountains. Meanwhile, Charles IV and the duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg managed to defeat a French army in the Battle of Konzer Brücke.

There were two other significant changes in the cast of military leaders during the year. On 17 August 1675, Charles IV died and was succeeded by his son, Charles V. He became the main Imperial commander and in this year managed to win the Siege of Philippsburg against the French. The city surrendered in September. At the end of the campaign season the Great Condé was forced to retire from all military duties because of his infirmities. After eleven years in retirement, he died on 11 December 1686.

In the last three years of the war, from 1676 through 1678 there was more siege activity than field battles. Furthermore, all the activity of the last three years achieved little change from what had already been achieved by the end of 1675. Louis had largely gone over to the defense in his aims for the war.[49] However, there also were some noteworthy naval actions in 1676. On 2 June 1676, the French navy under Louis-Victor Vivonne, duke de Rochechouart destroyed a Dutch fleet.[50] By this naval victory France, temporarily, achieved naval supremacy in the Mediterranean. In the previous naval action, Dutch admiral De Ruyter had already been killed during the inconclusive Battle of Augusta against a French fleet on 22 April 1676.[51] In the east, led by Marshal Crequy, the French army pushed the imperials back, retook most of Alsace and the front stabilized on the Rhine.

By 1678, Louis, once again, managed to break apart his opponents' coalition (as he had done to the Triple Alliance). However, Louis continued to be worried that the nations of Europe might still consolidate against him. In October 1677, Mary, daughter of James, Duke of York married William III, current the Stadtholder of the Republic. This was an ominous sign of a rapprochement between the Dutch and the English. So, Louis was in a hurry to shore up his military position before England re-entered the war, this time as enemy. Accordingly, the summer campaign of 1678 began very early in the spring. Louis moved his army into the Spanish Netherlands and besieged Ghent on 1 March 1678.[52] Louis was afraid that the anti-French parliament in England would act any day to force King Charles II of England back into the war. Ghent fell to the French on 10 March 1678. The French army then besieged Ypres on 15 March 1678. Ypres surrendered on 26 March 1678.[52]

The English sent an expeditionary force to Flanders in 1678, under the command of the Duke of Monmouth, to support the Dutch against the French; it did not see much action but some British units saw action at the Battle of Saint-Denis (the last battle of the war).[53]

The victories at Ghent and Ypres had gained Louis a strong bargaining position for France at the peace talks. France gained considerable territories under the terms of the Treaty of Nijmegen which was signed by the Dutch and France on 10 August 1678, but less than it aimed for.[54] Most notably, the French acquired the Franche-Comté and various territories in the Spanish Netherlands.[55] Nevertheless, the Dutch had thwarted the ambitions of two of the major royal dynasties of the time: the Stuarts and the Bourbons.

The war marked the beginning of a rivalry between two powerful men in Europe: William III (who would later invade England in support of the claims of himself and his wife, Queen Mary II, to the English throne, and Louis XIV. They, along with their respective allies, would be pitted against each other in a series of wars in the years that followed.

1678, peace and consequences

In 1678 Louis continued his conquests at the expense of the Spanish Netherlands, capturing Ghent and Ypres (25 March). The talks progressed in Nijmegen but were thwarted by the French decision to protect Swedish interests. With a new French victory in July, however, the United Provinces signed the Peace of Nijmegen in August 1678. Other peace treaties were signed with the other contenders in the coming months, where Spain lost the Franche-Comté and most of the various captured cities of the Spanish Netherlands to France.[55] The United Provinces, which ran the risk of being wiped out in 1672, could celebrate the reduction of some tariffs in its trade with France. Sweden, whose military tradition was not sufficient to stop the rise of Berlin, managed to leave the conflict with territorial losses negligible.

Although the outcome was at first glance inconclusive, it would have great importance for the events of the next 40 years. France, which in the final years of the war fought almost alone against a powerful coalition, left the episode as a great military power of continental Europe. Following the war, Louis XIV began to be referred to as the "Sun King".[56] Following the war, the United Provinces started to show signs of decay; their pre-eminence as a naval power would eventually be ceded to England. Ruled by William III after the Glorious Revolution, England was to become the sworn enemy of France. Spain and Sweden, shy participants in this conflict, lost importance and would suffer great territorial losses in the following decades.

The song "Auprès de ma blonde", or "Le Prisonnier de Hollande" ("The Prisoner of Holland"), in which a French woman grieves for her beloved who is held prisoner by the Dutch, appeared during or soon after the Franco-Dutch War – reflecting the contemporary situation of French sailors and soldiers being imprisoned in the Netherlands.

Chronological list of key events

- 1672 – Battle of Solebay (7 June – Third Anglo-Dutch War)

- 1673 – Battle of Schooneveld ( 7 and 14 June – Third Anglo-Dutch War)

- 1673 – Siege of Maastricht (13 – 26 June)

The Battle of Solebay, May 1672

The siege of Rheinberg by the French, 6 June 1672 - 1673 – Battle of Texel (21 August – Third Anglo-Dutch War)

The Battle of the Texel, August 1673 - 1673 – Siege of Bonn (end of October – 15 November)

The Siege of Besançon in 1674 - 1673 – Siege of Werl

- 1673 – Battle of Heringen

- 1674 – Occupation of Acadia

- 1674 – Siege of Besançon (April – May)

- 1674 – Battle of Sinsheim (or Sinzheim) (16 June)

- 1674 – Battle of Ladenburg (7 July)

- 1674 – Battle of Seneffe (11 August)

- 1674 – Battle of Enzheim (4 October)

- 1674 – Battle of Mulhouse (under Muehlhausen) (29 December)

- 1675 – Battle of Turckheim (5 January)

- 1675 – Battle of Fehrbellin (28 June – Brandenburg-Swedish War)

- 1675 – Battle of Nieder Sasbach (27 July)

- 1675 – Battle of Konzer Brücke (11 August)

- 1676 – Battle Alicudi (8 January)

- 1676 – Battle of Messina (25 March)

- 1676 – Battle of Golfo di Augusta (22 April)

- 1676 – Battle of Jasmund (25 May – Danish-Swedish (Scanian) War of 1675–1679)

- 1676 – Battle of Öland (11 June – Scanian War of 1675–1679)

- 1676 – Battle of Palermo (2 June)

- 1676 – Battle of Halmstad (17 August – Scanian War of 1675–1679)

- 1676 – Battle of Lund (4 December – Scanian War of 1675–1679)

- 1677 – Siege of Valenciennes (28 February – 17 March)

- 1677 – Siege of Cambrai (28 March – 17 April)

- 1677 – Battle of Cassel (11 April)

- 1677 – Battle of Køge Bay (1 July – Scanian War of 1675–1679)

- 1677 – Battle of Landskrona (24 July – Scanian War of 1675–1679)

- 1677 – Battle of Kochersberg (7 October)

- 1678 – Siege of Offenburg

- 1678 – Siege of Ypres (18 – 25 March)

- 1678 – Battle of Rheinfelden (6 July)

- 1678 – Battle of Gengenbach (23 July)

- 1678 – Battle of Saint-Denis (14 August)

See also

- War of Devolution (1667–68)

- War of the League of Augsburg or the War of the Grand Alliance (1688–97)

- War of the Spanish Succession (1701–14)

- For the "Dutch wars" of England, see Anglo–Dutch Wars

- For the quadruple alliance of 1718–1720, see War of the Quadruple Alliance

- Second Genoese-Savoyard War (1672–1673)

- Scanian War (1675–79)

- Auprès de ma blonde (French song derived from this war)

- Wars and battles involving Prussia

- Action of 1678

References

- ^ Stieve 1893, pp. 266–267.

- ^ a b c d Clodfelter 2017, p. 47.

- ^ 1672 Disaster Year, Rijksmuseum

- ^ Wolf 1962, p. 316.

- ^ Lynn, John (1996). The Wars of Louis XIV, 1667-1714 (Modern Wars In Perspective). Longman. p. 109. ISBN 978-0582056299.

- ^ Sommerville 2008.

- ^ a b Smith 1965, p. 200.

- ^ Lynn, John (1996). The Wars of Louis XIV, 1667-1714 (Modern Wars In Perspective). Longman. pp. 109–110. ISBN 978-0582056299.

- ^ J. P. Kenyon, The History Men. The Historical Profession in England since the Renaissance. Second Edition (Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1993), pp. 67-68.

- ^ a b c Lynn 1999, p. 113.

- ^ a b Lynn 1999, p. 115.

- ^ Reinders, Michel (2013). Printed Pandemonium: Popular Print and Politics in the Netherlands 1650-72. Brill. pp. 108–110. ISBN 978-9004243187.

- ^ Young, William (2004). International Politics and Warfare in the Age of Louis XIV and Peter the Great. iUniverse. p. 131. ISBN 978-0595329922.

- ^ Lynn 1999, p. 114.

- ^ Lynn 1999, p. 117.

- ^ Lynn 1999, p. 118.

- ^ Childs, John (1991). The Nine Years' War and the British Army, 1688-1697: The Operations in the Low Countries (2013 ed.). Manchester University Press. pp. 32–33. ISBN 0719089964.

- ^ Churchill 1933, p. 84.

- ^ Harris, Tim. "Scott [formerly Crofts], James, duke of Monmouth and first Duke of Buccleuch (1649–1685)". Oxford DNB. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- ^ Linklater, Magnus. "Graham, John, first viscount of Dundee [known as Bonnie Dundee". Oxford DNB. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- ^ Lynn 1999, p. 120.

- ^ Churchill 1933, p. 89.

- ^ Young, William (2004). International Politics and Warfare in the Age of Louis XIV and Peter the Great. iUniverse. p. 131. ISBN 978-0595329922.

- ^ Young, William (2004). International Politics and Warfare in the Age of Louis XIV and Peter the Great. iUniverse. p. 132. ISBN 978-0595329922.

- ^ Lynn 1999, p. 121.

- ^ Young, William (2004). International Politics and Warfare in the Age of Louis XIV and Peter the Great. iUniverse. p. 132. ISBN 978-0595329922.

- ^ Boxer, CR (1969). "Some Second Thoughts on the Third Anglo-Dutch War, 1672-1674". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 19: 74–75. doi:10.2307/3678740. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ^ Palmer, Michael (2005). Command at Sea: Naval Command and Control Since the Sixteenth Century (2007 ed.). Harvard University Press;. pp. 60–61. ISBN 978-0674024113.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Churchill 1933, p. 95.

- ^ Churchill 1933, p. 94.

- ^ Boxer, CR (1969). "Some Second Thoughts on the Third Anglo-Dutch War, 1672-1674". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 19: 88–90. doi:10.2307/3678740. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ^ Davenport, Frances (1917). "European Treaties bearing on the History of the United States and its Dependencies". p. 238. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- ^ Lynn 1999, p. 128.

- ^ Linklater, Magnus. "Graham, John, first viscount of Dundee [known as Bonnie Dundee". Oxford DNB. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- ^ Lynn. p. 129.

- ^ Lynn 1999, p. 129.

- ^ Lynn 1999, p. 131.

- ^ Lynn 1999, p. 132.

- ^ a b c d e Lynn 1999, p. 135.

- ^ Churchill 1933, p. 105.

- ^ Lynn 1999, pp. 132–133.

- ^ Lynn 1999, p. 133.

- ^ Lynn 1999, pp. 133–135.

- ^ Lynn 1999, p. 136-137.

- ^ Lynn 1999, p. 137.

- ^ Lynn 1999, pp. 138–139.

- ^ Lynn

- ^ Lynn 1999, p. 141.

- ^ Lynn 1999, p. 144.

- ^ Lynn 1999, pp. 148–149.

- ^ Lynn 1999, p. 148.

- ^ a b Lynn 1999, p. 153.

- ^ Childs 2013, pp. 185–190.

- ^ Lynn 1999, p. 154.

- ^ a b Mitford 1966, p. 32.

- ^ Lynn 1999, p. 159.

Bibliography

- Felix Stieve (1893), "Sporck, Johann Graf von", Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (in German), vol. 35, Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 264–267

- Childs, John (2013), Army of Charles II, Routledge, pp. 185–190, ISBN 978-1-134-52859-2

- Churchill, Winston S., Marlborough: His Life and Times, Book I (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1933). ISBN 0-226-10633-0.

- Clodfelter, M. (2017). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492-2015 (4th ed.). Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0786474707.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Koch, H. W., A History of Prussia (Dorset Press: New York, 1978).

- Lynn, John A., The Wars of Louis XIV: 1667–1714 (Longman Publishers: Harlow, England, 1999).

- Mitford, Nancy, The Sun King: Louis XIV at Versailles (Harper & Row Publishers: New York, 1966).

- Sommerville, J. P. (16 January 2008), The wars of Louis XIV

- Smith, Rhea Marsh, Spain: A Modern History (University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1965).

- Wolf, John B., The Emergence of European Civilization (Harper & Row: New York, 1962).

- Frost, Robert (2000), The Northern Wars: War, State and Society in Northeastern Europe 1558-1721, Pearson Education.

Further reading

- Bély, Lucien, La France Moderne (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1994).

- Eggenberger, David. An Encyclopedia of Battles (New York: Dover Publications, 1985). ISBN 0-486-24913-1.

- Pujo, Bernard, Le Grand Condé (Éditions Albin Michel, 1995)

- Souza, Marcos da Cunha e et al., História Militar Geral I (Palhoça: UnisulVirtual, 2009).

- Tarnstrom, Ronald, The Sword of Scandinavia (Lindsborg: Trogen Books, 1996).

- Weygand, General, Turenne (Paris: American Edition, 1929).

External links

- Use dmy dates from August 2013

- 1670s conflicts

- 1670s in France

- 1670s in the Dutch Republic

- Wars involving Brandenburg-Prussia

- Wars involving Cologne

- Wars involving England

- Wars involving France

- Wars involving the Holy Roman Empire

- Wars involving Spain

- Wars involving Sweden

- Wars involving the Dutch Republic

- Wars involving the Netherlands