Freedom for the Thought That We Hate

Cover art of the original publication | |

| Author | Anthony Lewis |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Cover: Brent Wilcox Jacket: Anita Van De Ven Jacket photo: Ken Cedeno |

| Language | English |

| Series | Basic Ideas |

| Subject | Freedom of speech – United States |

| Genre | Constitutional Law |

| Published | 2007 (Basic Books) |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Hardcover |

| Pages | 240 |

| ISBN | 978-0-465-03917-3 |

| OCLC | 173659591 |

| 342.7308/53 | |

| LC Class | KF4770.L49 |

Freedom for the Thought That We Hate: A Biography of the First Amendment is a 2007 non-fiction book by journalist Anthony Lewis about freedom of speech, freedom of the press, freedom of thought, and the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. The book starts by quoting the First Amendment, which prohibits the U.S. Congress from creating legislation which limits free speech or freedom of the press. Lewis traces the evolution of civil liberties in the U.S. through key historical events. He provides an overview of important free speech case law, including U.S. Supreme Court opinions in Schenck v. United States (1919), Whitney v. California (1927), United States v. Schwimmer (1929), New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964), and New York Times Co. v. United States (1971).

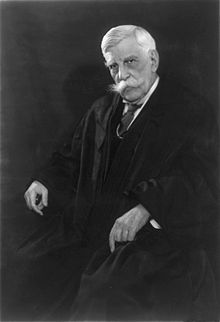

The title of the book is drawn from the dissenting opinion by Supreme Court Associate Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. in United States v. Schwimmer. Holmes wrote that "if there is any principle of the Constitution that more imperatively calls for attachment than any other, it is the principle of free thought—not free thought for those who agree with us but freedom for the thought that we hate."[1] Lewis warns the reader against the potential for government to take advantage of periods of fear and upheaval in a post-9/11 society to suppress freedom of speech and criticism by citizens.

The book was positively received by reviewers, including Jeffrey Rosen in The New York Times, Richard H. Fallon in Harvard Magazine, Nat Hentoff, two National Book Critics Circle members, and Kirkus Reviews. Jeremy Waldron commented on the work for The New York Review of Books and criticized Lewis' stance towards freedom of speech with respect to hate speech. Waldron elaborated on this criticism in his book The Harm in Hate Speech (2012), in which he devoted a chapter to Lewis' book. This prompted a critical analysis of both works in The New York Review of Books in June 2012 by former Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens.

Contents

Freedom for the Thought That We Hate analyzes the value of freedom of speech and presents an overview of the historical development of rights afforded by the First Amendment to the United States Constitution.[2] Its title derives from Justice Holmes' admonition, in his dissenting opinion in United States v. Schwimmer (1929),[1][3][4] that the First Amendment's guarantees are most worthy of protection in times of fear and upheaval, when calls for suppression of dissent are most strident and superficially appealing.[1][3][4] Holmes wrote that "if there is any principle of the Constitution that more imperatively calls for attachment than any other, it is the principle of free thought—not free thought for those who agree with us but freedom for the thought that we hate."[1][3][4]

The book starts by quoting the First Amendment, which prohibits the U.S. Congress from creating legislation that limits free speech or freedom of the press.[3][5] The author analyzes the impact of this clause and refers to the writer of the United States Constitution, James Madison, who believed that freedom of the press would serve as a form of separation of powers to the government.[5] Lewis writes that an expansive respect for freedom of speech informs the reader as to why citizens should object to governmental attempts to block the media from reporting about the causes of a controversial war.[5] Lewis warns that, in a state in which controversial views are not allowed to be spoken, citizens and reporters merely serve as advocates for the state itself.[5] He recounts key historic events in which fear led to overreaching acts by the government, particularly from the executive branch.[5] The author gives background on the century-long process by which the U.S. judicial system began defending publishers and writers from attempts at suppression of speech by the government.[4]

In 1798, the federal government, under President John Adams, passed the Alien and Sedition Acts, which deemed "any false, scandalous and malicious writing or writings against the government of the United States" a criminal act.[3][6] The Alien and Sedition Acts were used for political impact against members of the Republican Party in order to punish them for criticizing the government.[5] Thomas Jefferson was elected the next president in 1800; Lewis cites this as an example of the American public's dissatisfaction with Adams' actions against freedom of speech.[5][7] After taking office in 1801, Jefferson issued pardons to those convicted under the Alien and Sedition Acts.[3][7] Lewis interprets later historical events as affronts to freedom of speech, including the Sedition Act of 1918, which effectively outlawed criticism of the government's conduct of WW I; and the McCarran Internal Security Act and Smith Act, which were used to imprison American communists who were critical of the government during the McCarthy era.[5]

During World War I, with increased fear among the American public and attempts at suppression of criticism by the government, the First Amendment was given wider examination in the U.S. Supreme Court.[5] Lewis writes that Associate Justices Louis Brandeis and Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., began to interpret broader support for freedom of speech imparted by the First Amendment.[5] Holmes wrote in the case of Schenck v. United States that freedom of speech must be defended except for situations in which "substantive evils" are caused through a "clear and present danger" arising from such speech.[5][8] The author reflects on his view of speech in the face of imminent danger in an age of terrorism.[6] He writes that the U.S. Constitution permits suppression of speech in situations of impending violence, and cautions use of the law to suppress expressive acts including burning a flag or using offensive slang terms.[6] Lewis asserts that punitive measures can be taken against speech which incites terrorism to a group of people willing to commit such acts.[6]

The book recounts an opinion written by Brandeis and joined by Holmes in the 1927 case of Whitney v. California which further developed the notion of the power of the people to speak out.[4] Brandeis and Holmes emphasized the value of liberty, and identified the most dangerous factor to freedom as an apathetic society averse to voicing their opinions in public.[4][9]

"There will always be authorities who try to make their own lives more comfortable by suppressing critical comment. [...] But I am convinced that the fundamental American commitment to free speech, disturbing speech, is no longer in doubt."

—Anthony Lewis, Introduction,

Freedom for the Thought That We Hate[3]

In the 1964 Supreme Court case of New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, the court ruled that speech about issues of public impact should be unrestricted, vigorous and public, even if such discussion communicates extreme negative criticism of public servants and members of government.[3][10] Lewis praises this decision, and writes that it laid the groundwork for a press more able to perform investigative journalism concerning controversies, including the Watergate scandal and the Vietnam War.[3] He cites the New York Times Co. v. Sullivan decision as an example of "Madisonian" philosophy towards freedom of speech espoused by James Madison.[7] The author examines the 1971 U.S. Supreme Court case of New York Times Co. v. United States, and endorses the court's decision, which allowed the press to publish classified material relating to the Vietnam War.[5][11]

The author questions the actions of the media with respect to privacy. He observes that public expectations regarding morality and what constitutes an impermissible violation of the right to privacy has changed over time.[5] Lewis cites the dissenting opinion by Brandeis in Olmstead v. United States, which supported a right to privacy.[5][12]

Lewis warns that, during periods of heightened anxiety, the free speech rights of Americans are at greater risk: "there will always be authorities who try to make their own lives more comfortable by suppressing critical comment."[3] He concludes that the evolution of interpretation of the rights afforded by the First Amendment has created stronger support for freedom of speech.[3]

Themes

The book's central theme is a warning that, in times of strife and increased fear, there is a danger of repression and suppression of dissent by those in government who seek to limit freedom of speech.[13] In an interview with the author, Deborah Solomon of The New York Times Magazine wrote that American politics has frequently used fear to justify repression.[13] Lewis pointed out to Solomon that, under the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918, individuals who protested against President Woodrow Wilson's sending of soldiers to Russia were tried and given a twenty-year jail sentence.[13] The author explained that his motivation for writing the book was to recognize the unparalleled civil liberties in the U.S., including freedom of speech and freedom of the press.[13] He identified reductions in freedoms of citizens as a result of governmental action taken after the September 11 attacks.[14]

Freedom for the Thought That We Hate discusses the capability and liberty of citizens to criticize their government.[15] Lewis asserts that the U.S. has the most unreserved speech of any nation.[15][16] Law professor Jeremy Waldron gave the example of his ability to criticize the president or call the vice president and Secretary of Defense war criminals, without fear of retribution from law enforcement for such statements.[15] The book contrasts present-day free speech liberties afforded to Americans and those possessed by citizens in earlier centuries.[15] The author argues that the scope of civil liberties in the U.S. has increased over time owing to a desire for freedom among its people being held as an integral value.[16] Lewis observes in contemporary application of the law, presidents are the subject of satire and denunciation.[15] He notes that it is unlikely a vociferous critic would face a jail sentence simply for voicing such criticism.[15]

Release and reception

Freedom for the Thought That We Hate was first published by Basic Books, a member of the Perseus Books Group, in New York in 2007, with the subtitle, A Biography of the First Amendment.[18][19] For just the second printing, in both New York and London in 2008, the book's subtitle was simplified to Tales of the First Amendment. That change was reverted for the remaining printings, including the paperback edition in 2009 and a large print edition in 2010.[18][20][21] E-book versions were released for the first, third and fourth printings; an audiobook was released with the second printing, and re-released with the fourth.[18][22][23] The book has also been translated into Chinese, and was published in Beijing in 2010.[24]

The book was positively received by critics. Jeffrey Rosen, who reviewed the book for The New York Times, was surprised by the author's departure from traditional civil libertarian views.[25] Rosen pointed out that Lewis did not support absolute protection for journalists from breaking confidentiality with their anonymous sources, even in situations involving criminal acts.[25] Nat Hentoff called the book an engrossing and accessible survey of the First Amendment.[4] Kirkus Reviews considered the book an excellent chronological account of the First Amendment, subsequent legislation, and case law.[26]

Richard H. Fallon reviewed the book for Harvard Magazine, and characterized Freedom for the Thought That We Hate as a clear and captivating background education to U.S. freedom of speech legislation.[27] Fallon praised the author's ability to weave descriptions of historical events into an entertaining account.[27] Robyn Blumner of the St. Petersburg Times wrote that Lewis aptly summarized the development of the U.S. Constitution's protections of freedom of speech and of the press.[28] She observed that the book forcefully presented the author's admiration of brave judges who had helped to develop interpretation of the U.S. Constitution's protections of the rights of freedom of expression as a defense against censorship.[28]

Writing for the Hartford Courant, Bill Williams stated that the book should be mandatory reading for high school and college students.[3] Anne Phillips wrote in her review for The News-Gazette that the book is a concise and well-written description of the conflicts the country faces when grappling with the notions of freedom of expression, free speech, and freedom of the press.[29] Writing for The Christian Science Monitor, Chuck Leddy noted that the author helps readers understand the importance of freedom of speech in a democracy, especially during a period of military conflict when there is increased controversy over the appropriateness of dissent and open dialogue.[5]

Jeremy Waldron reviewed the book for The New York Review of Books, and was critical of Lewis' broad stance towards freedom of speech with respect to hate speech.[30] Waldron later elaborated this position in his 2012 book The Harm in Hate Speech, in which he devoted an entire chapter to Lewis' book.[31] Waldron emphasized that the problem with an expansive view of free speech is not the harm of hateful thoughts, but rather the negative impact resulting from widespread publication of the thoughts.[31] He questioned whether children of racial groups criticized by widely published hate speech would be able to succeed in such an environment.[31] Former U.S. Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens analyzed The Harm in Hate Speech and discussed Freedom for the Thought That We Hate, in a review for The New York Review of Books.[17] Justice Stevens recounted Lewis' argument that an acceptance of hate speech is necessary, because attempts to regulate it would cause encroachment upon expression of controversial viewpoints.[17] He pointed out that Lewis and Waldron agreed that Americans have more freedom of speech than citizens of any other country.[17] In his review, Stevens cited the 2011 decision in Snyder v. Phelps as evidence that the majority of the U.S. Supreme Court supported the right of the people to express hateful views on matters of public importance.[17] Stevens concluded that, although Waldron was unsuccessful in convincing him that legislators should ban all hate speech, The Harm in Hate Speech persuaded him that government leaders should refrain from using such language themselves.[17]

See also

- Censorship in the United States

- Civil liberties in the United States

- Free speech fights

- Freedom of speech in the United States

- Freedom of the press in the United States

References

- ^ a b c d e Holmes, Jr., Oliver Wendell (May 27, 1929). "Dissenting opinion". United States v. Schwimmer. Supreme Court of the United States. p. .

- ^ Esposito, Martha (January 13, 2008). "Book Beat: New books for the new year include county native's nonfiction". Burlington County Times. Willingboro, New Jersey. p. 3; Section: Outlook.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Williams, Bill (February 10, 2008). "The majesty of the First Amendment". Hartford Courant. p. G4; Section: Arts.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hentoff, Nat (January 30, 2008). "The right from which others flow". Tulsa World. Tulsa, Oklahoma. p. A13.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Leddy, Chuck (January 8, 2008). "A balance between free speech and fear". The Christian Science Monitor. p. 16; Section: Features, Books.

- ^ a b c d Mitchell, Thomas (February 10, 2008). "Freedom for – speech we hate". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Las Vegas, Nevada. p. 2D.

- ^ a b c Barcousky, Len (May 18, 2008). "'Freedom For the Thought That We Hate' by Anthony Lewis – How First Amendment survives". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Pennsylvania. p. E-4. Archived from the original on February 19, 2014. Retrieved November 6, 2012.

- ^ Holmes, Jr., Oliver Wendell (March 3, 1919). "Majority opinion". Schenck v. United States. Supreme Court of the United States. p. .

- ^ Brandeis, Louis; Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. (May 16, 1927). "Concurring opinion". Whitney v. California. Supreme Court of the United States. p. .

- ^ Brennan, Jr., William J. (March 9, 1964). "Majority opinion". New York Times Co. v. Sullivan. Supreme Court of the United States. p. .

- ^ Per curiam (June 30, 1971). "Majority opinion". New York Times Co. v. United States. Supreme Court of the United States. p. .

- ^ Brandeis, Louis (June 4, 1928). "Dissenting opinion". Olmstead v. United States. Supreme Court of the United States. p. .

- ^ a b c d Solomon, Deborah (December 23, 2007). "Questions for Anthony Lewis – Speech Rules". The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved November 6, 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ Neier, Aryeh (January 2008). "Review – May I Speak Freely? – Anthony Lewis on the First Amendment's march to victory". Columbia Journalism Review. Archived from the original on June 11, 2007. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f Waldron, Jeremy (May 29, 2008). "Free Speech & the Menace of Hysteria". The New York Review of Books. Vol. 55, no. 9. Archived from the original on October 18, 2013. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Williams, Juan (2011). Muzzled: The Assault on Honest Debate. New York: Crown. pp. 244–245, 248–250. ISBN 0307952010.

- ^ a b c d e f Stevens, John Paul (June 7, 2012). "Should Hate Speech Be Outlawed?". The New York Review of Books. Vol. 59, no. 10. Archived from the original on May 19, 2012. Retrieved November 6, 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c OCLC. "Formats and Editions of Freedom for the Thought That We Hate: A Biography of the First Amendment (Book, 2007)". WorldCat. OCLC 173659591. Archived from the original on September 23, 2013. Retrieved September 18, 2013.

- ^ Lewis, Anthony (2007). Freedom for the Thought That We Hate: A Biography of the First Amendment. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 9780465039173.

- ^ OCLC. "Formats and Editions of Freedom for the Thought That We Hate: Tales of the First Amendment (Book, 2008)". WorldCat. OCLC 181068910. Archived from the original on September 23, 2013. Retrieved September 18, 2013.

- ^ Lewis, Anthony (2008). Freedom for the Thought That We Hate: Tales of the First Amendment. London: Perseus Running (Distributor). ISBN 9780465039173.

- ^ Lewis, Anthony (2010). Freedom for the Thought That We Hate. New York: Perseus Books Group. ISBN 9780465012930.

- ^ "Freedom for the Thought That We Hate: A Biography of the First Amendment (Audiobook, 2010)". WorldCat. OCLC. 2013. OCLC 496960479. Archived from the original on September 23, 2013. Retrieved September 18, 2013.

- ^ "言论的边界 : 美国宪法第一修正案简史 / Yan lun de bian jie : Meiguo xian fa di yi xiu zheng an jian shi (Book, 2010)". WorldCat. OCLC. 2013. OCLC 657029139. Archived from the original on September 23, 2013. Retrieved September 18, 2013.

- ^ a b Rosen, Jeffrey (January 13, 2008). "Say What You Will – Freedom for the Thought That We Hate – Anthony Lewis – Book review". The New York Times. Retrieved November 6, 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ "Freedom for the Thought That We Hate". Kirkus Reviews. October 15, 2007. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013. Retrieved November 6, 2012.

- ^ a b Fallon, Richard H. (May–June 2008). "Book Review – Freeing Speech – How judge-made law gave meaning to the First Amendment". Harvard Magazine. pp. 27–30. Archived from the original on October 18, 2011. Retrieved November 6, 2012.

- ^ a b Blumner, Robyn (March 2, 2008). "Freedom Comes First". St. Petersburg Times. Florida. p. 10L; Section: Latitudes.

- ^ Phillips, Anne (September 20, 2009). "Manners and freedom taken for granted". The News-Gazette. Champaign-Urbana, Illinois. p. F–3.

- ^ Liptak, Adam (June 12, 2008). "Unlike Others, U.S. Defends Freedom to Offend in Speech". The New York Times. p. A–10. Retrieved September 21, 2013.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Waldron, Jeremy (2012). "Anthony Lewis's Freedom for the Thought That We Hate". The Harm in Hate Speech. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 18–34. ISBN 9780674065895.

Further reading

- Curtis, Michael Kent (2000). Free Speech, "The People's Darling Privilege": Struggles for Freedom of Expression in American History. Duke University Press. ISBN 0822325292.

- Godwin, Mike (2003). Cyber Rights: Defending Free Speech in the Digital Age. MIT Press. ISBN 0262571684.

- Grossman, Wendy M. (1997). Net.wars. New York University Press. ISBN 0814731031.

- McLeod, Kembrew; Lawrence Lessig (2007). Freedom of Expression: Resistance and Repression in the Age of Intellectual Property. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0816650314.

- Nelson, Samuel P. (2005). Beyond the First Amendment: The Politics of Free Speech and Pluralism. The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0801881730.

External links

- "About the book". Perseus Academic. The Perseus Books Group. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- "Anthony Lewis". Nieman Watchdog. President and Fellows of Harvard College. 2005. Archived from the original on October 23, 2005. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- "Freedom for the Thought That We Hate, Part I". PBS Video. PBS. January 17, 2008. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- James Goodale (May 18, 2008). "Digital Age: When Should The First Amendment Lose?". Goodale TV. YouTube. Archived from the original on October 17, 2013. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- "After Words with Anthony Lewis". C-SPAN. National Cable Satellite Corporation. February 11, 2008. Retrieved October 18, 2014.