General Data Protection Regulation

| European Union regulation | |

| |

| Title | Regulation on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (Data Protection Directive) |

|---|---|

| Made by | European Parliament and Council |

| Journal reference | L119, 4/5/2016, p. 1–88 |

| History | |

| Date made | 14 April 2016 |

| Implementation date | 25 May 2018 |

| Preparative texts | |

| Commission proposal | COM/2012/010 final - 2012/0010 (COD) |

| Other legislation | |

| Replaces | Data Protection Directive |

| Current legislation | |

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) (EU) 2016/679 is a regulation in EU law on data protection and privacy for all individuals within the European Union and the European Economic Area. It also addresses the export of personal data outside the EU and EEA. The GDPR aims primarily to give control to citizens and residents over their personal data and to simplify the regulatory environment for international business by unifying the regulation within the EU.[1]

Superseding the Data Protection Directive, the regulation contains provisions and requirements pertaining to the processing of personally identifiable information of data subjects inside the European Union. Business processes that handle personal data must be built with privacy by design and by default, meaning that personal data must be stored using pseudonymisation or full anonymization, and use the highest-possible privacy settings by default, so that the data is not available publicly without explicit consent, and cannot be used to identify a subject without additional information stored separately. No personal data may be processed unless it is done under a lawful basis specified by the regulation, or if the data controller or processor has received explicit, opt-in consent from the data's owner. The business must allow this permission to be withdrawn at any time.

A processor of personal data must clearly disclose what data is being collected and how, why it is being processed, how long it is being retained, and if it is being shared with any third-parties. Users have the right to request a portable copy of the data collected by a processor in a common format, and the right to have their data erased under certain circumstances. Public authorities, and businesses whose core activities centre around regular or systematic processing of personal data, are required to employ a data protection officer (DPO), who is responsible for managing compliance with the GDPR. Businesses must report any data breaches within 72 hours if they have an adverse effect on user privacy.

It was adopted on 14 April 2016,[2] and after a two-year transition period, becomes enforceable on 25 May 2018.[3][4] Because the GDPR is a regulation, not a directive, it does not require national governments to pass any enabling legislation and is directly binding and applicable.[5]

Content

The regulation contains the following key requirements:[6][7]

Scope

The regulation applies if the data controller (an organisation that collects data from EU residents), or processor (an organisation that processes data on behalf of a data controller like cloud service providers), or the data subject (person) is based in the EU. Under certain circumstances[8], the regulation also applies to organisations based outside the EU if they collect or process personal data of individuals located inside the EU.

According to the European Commission, "personal data is any information relating to an individual, whether it relates to his or her private, professional or public life. It can be anything from a name, a home address, a photo, an email address, bank details, posts on social networking websites, medical information, or a computer’s IP address."[9]

The regulation does not purport to apply to the processing of personal data for national security activities or law enforcement of the EU; however, industry groups concerned about facing a potential conflict of laws have questioned whether Article 48[10] of the GDPR could be invoked to seek to prevent a data controller subject to a third country's laws from complying with a legal order from that country's law enforcement, judicial, or national security authorities to disclose to such authorities the personal data of an EU person, regardless of whether the data resides in or out of the EU. Article 48 states that any judgement of a court or tribunal and any decision of an administrative authority of a third country requiring a controller or processor to transfer or disclose personal data may not be recognised or enforceable in any manner unless based on an international agreement, like a mutual legal assistance treaty in force between the requesting third (non-EU) country and the EU or a member state. The data protection reform package also includes a separate Data Protection Directive for the police and criminal justice sector[11] that provides rules on personal data exchanges at national, European, and international levels.

A single set of rules will apply to all EU member states. Each member state will establish an independent supervisory authority (SA) to hear and investigate complaints, sanction administrative offences, etc. SAs in each member state will co-operate with other SAs, providing mutual assistance and organising joint operations. If a business has multiple establishments in the EU, it will have a single SA as its "lead authority", based on the location of its "main establishment" where the main processing activities take place. The lead authority will act as a "one-stop shop" to supervise all the processing activities of that business throughout the EU[12][13] (Articles 46–55 of the GDPR). A European Data Protection Board (EDPB) will coordinate the SAs. EDPB will replace the Article 29 Data Protection Working Party. There are exceptions for data processed in an employment context or in national security that still might be subject to individual country regulations (Articles 2(2)(a) and 88 of the GDPR).

Lawful basis for processing

Data may not be processed unless there is at least one lawful basis to do so:[14]

- The data subject has given consent to the processing of personal data for one or more specific purposes.

- Processing is necessary for the performance of a contract to which the data subject is party or to take steps at the request of the data subject prior to entering into a contract.

- Processing is necessary for compliance with a legal obligation to which the controller is subject.

- Processing is necessary to protect the vital interests of the data subject or of another natural person.

- Processing is necessary for the performance of a task carried out in the public interest or in the exercise of official authority vested in the controller.

- Processing is necessary for the purposes of the legitimate interests pursued by the controller or by a third party unless such interests are overridden by the interests or fundamental rights and freedoms of the data subject, which require protection of personal data, in particular if the data subject is a child.

If consent is used as the lawful basis for processing, consent must be explicit for data collected and the purposes data is used for (Article 7; defined in Article 4). Consent for children[15] must be given by the child’s parent or custodian, and verifiable (Article 8). Data controllers must be able to prove "consent" (opt-in) and consent may be withdrawn.[16]

The area of GDPR consent has a number of implications for businesses who record calls as a matter of practice. The typical “calls are recorded for training and security purposes” warnings will no longer be sufficient to gain assumed consent to record calls. Additionally, when recording has commenced, should the caller withdraw their consent then the agent receiving the call must be able to stop a previously started recording and ensure the recording does not get stored.[17]

Responsibility and accountability

To be able to demonstrate compliance with the GDPR, the data controller must implement measures which meet the principles of data protection by design and by default. Privacy by design and by default (Article 25) require data protection measures to be designed into the development of business processes for products and services. Such measures include pseudonymising personal data, by the controller, as soon as possible (Recital 78). It is the responsibility and the liability of the data controller to implement effective measures and be able to demonstrate the compliance of processing activities even if the processing is carried out by a data processor on behalf of the controller (Recital 74).

When data is collected, users must be clearly informed about the extent of data collection, the legal basis for processing of personal data, how long data is retained, if data is being transferred to a third-party and/or outside the EU, and disclosure of any automated decision-making that is made on a solely-algorithmic basis. Users must be provided with contact details for the data controller and their designated Data Protection Officer, where applicable. Users must also inform users of their rights under GDPR, including their right to revoke their consent for data processing at any time, their right to view their personal data and access an overview of how it is being processed, the right to obtain a copy of the stored data, erasure of data under certain circumstances, the right to contest any automated decision-making that was made on a solely-algorithmic basis, and the right to file complaints with a Data Protection Authority.[18][19]

Many media outlets have commented on the introduction of a "right to explanation" of algorithmic decisions,[20][21] but legal scholars have since argued that the existence of such a right is highly unclear without judicial tests and is limited at best.[22][23]

Data protection impact assessments (Article 35) have to be conducted when specific risks occur to the rights and freedoms of data subjects. Risk assessment and mitigation is required and prior approval of the national data protection authorities (DPAs) is required for high risks.

Data protection by design and by default

Data protection by design and by default (Article 25) requires data protection to be designed into the development of business processes for products and services. Privacy settings must therefore be set at a high level by default, and technical and procedural measures should be taken by the controller to make sure that the processing, throughout the whole processing lifecycle, complies with the regulation. Controllers should also implement mechanisms to ensure that personal data is not processed unless necessary for each specific purpose.

A report[24] by the European Union Agency for Network and Information Security elaborates on what needs to be done to achieve privacy and data protection by default. It specifies that encryption and decryption operations must be carried out locally, not by remote service, because both keys and data must remain in the power of the data owner if any privacy is to be achieved. The report specifies that outsourced data storage on remote clouds is practical and relatively safe if only the data owner, not the cloud service, holds the decryption keys.

Pseudonymisation

The GDPR refers to pseudonymisation as a process that is required when data is stored (as an alternative to the other option of complete data anonymization)[25] to transform personal data in such a way that the resulting data cannot be attributed to a specific data subject without the use of additional information. An example is encryption, which renders the original data unintelligible and the process cannot be reversed without access to the correct decryption key. The GDPR requires for the additional information (such as the decryption key) to be kept separately from the pseudonymised data.

Another example of pseudonymisation is tokenization, which is a non-mathematical approach to protecting data at rest that replaces sensitive data with non-sensitive substitutes, referred to as tokens. The tokens have no extrinsic or exploitable meaning or value. Tokenization does not alter the type or length of data, which means it can be processed by legacy systems such as databases that may be sensitive to data length and type.

That requires much fewer computational resources to process and less storage space in databases than traditionally-encrypted data. That is achieved by keeping specific data fully or partially visible for processing and analytics while sensitive information is kept hidden.

Pseudonymisation is recommended to reduce the risks to the concerned data subjects and also to help controllers and processors to meet their data protection obligations (Recital 28).

The GDPR encourages the use of pseudonymisation to "reduce risks to the data subjects" (Recital 28).[26]

Right of access

The right of access (Article 15) is a data subject right.[27] It gives citizens the right to access their personal data and information about how this personal data is being processed. A data controller must provide, upon request, an overview of the categories of data that are being processed (Article 15(1)(b)) as well as a copy of the actual data (Article 15(3)). Furthermore, the data controller has to inform the data subject on details about the processing, such as the purposes of the processing (Article 15(1)(a)), with whom the data is shared (Article 15(1)(c)), and how it acquired the data (Article 15(1)(g)).

A data subject must be able to transfer personal data from one electronic processing system to and into another, without being prevented from doing so by the data controller. Data that has been sufficiently anonymised is excluded, but data that has been only de-identified but remains possible to link to the individual in question, such as by providing the relevant identifier, is not.[28] Both data being 'provided' by the data subject and data being 'observed', such as about behaviour, are included. In addition, the data must be provided by the controller in a structured and commonly used standard electronic format. The right to data portability is provided by Article 20 of the GDPR.[7] Legal experts see in the final version of this measure a "new right" created that "reaches beyond the scope of data portability between two controllers as stipulated in [Article 20]".[29]

Right to erasure

A right to be forgotten was replaced by a more limited right of erasure in the version of the GDPR that was adopted by the European Parliament in March 2014.[30][31] Article 17 provides that the data subject has the right to request erasure of personal data related to them on any one of a number of grounds, including noncompliance with Article 6(1) (lawfulness) that includes a case (f) if the legitimate interests of the controller is overridden by the interests or fundamental rights and freedoms of the data subject, which require protection of personal data (see also Google Spain SL, Google Inc. v Agencia Española de Protección de Datos, Mario Costeja González).

Records of processing activities

Records of processing activities must be maintained that include purposes of the processing, categories involved and envisaged time limits. The records must be made available to the supervisory authority on request (Article 30).[32]

Data protection officer

If the processing is carried out by a public authority, except for courts or independent judicial authorities when acting in their judicial capacity or if, in the private sector, processing is carried out by a controller whose core activities consist of processing operations that require regular and systematic monitoring of the data subjects, or processing on a large scale of special categories of data pursuant to Article 9 and personal data relating to criminal convictions and offences referred to in Article 10[33] a person with expert knowledge of data protection law and practices should assist the controller or processor to monitor internal compliance with this regulation.

The DPO is similar to a compliance officer and is also expected to be proficient at managing IT processes, data security (including dealing with cyberattacks) and other critical business continuity issues around the holding and processing of personal and sensitive data. The skill set required stretches beyond understanding legal compliance with data protection laws and regulations.

The appointment of a DPO in a large organization will be a challenge for the board as well as for the individual concerned.[citation needed] There are myriad governance and human factor issues that organisations and companies will need to address given the scope and nature of the appointment. In addition, the DPO must have a support team and will also be responsible for continuing professional development to be independent of the organization that employs them, effectively as a "mini-regulator."

More details on the function and the role of data protection officer were given on 13 December 2016 (revised 5 April 2017) in a guideline document.[34]

Data breaches

Under the GDPR, the data controller is under a legal obligation to notify the supervisory authority without undue delay unless the breach is unlikely to result in a risk to the rights and freedoms of the individuals. There is a maximum of 72 hours after becoming aware of the data breach to make the report (Article 33). Individuals have to be notified if adverse impact is determined (Article 34). In addition, the data processor will have to notify the controller without undue delay after becoming aware of a personal data breach (Article 33).

However, the notice to data subjects is not required if the data controller has implemented appropriate technical and organisational protection measures that render the personal data unintelligible to any person who is not authorised to access it, such as encryption (Article 34).

Sanctions

The following sanctions can be imposed:

- a warning in writing in cases of first and non-intentional noncompliance

- regular periodic data protection audits

- a fine up to €10 million or up to 2% of the annual worldwide turnover of the preceding financial year in case of an enterprise, whichever is greater, if there has been an infringement of the following provisions: (Article 83, Paragraph 5 & 6[35])

- the obligations of the controller and the processor pursuant to Articles 8, 11, 25 to 39, and 42 and 43

- the obligations of the certification body pursuant to Articles 42 and 43

- the obligations of the monitoring body pursuant to Article 41(4)

- a fine up to €20 million or up to 4% of the annual worldwide turnover of the preceding financial year in case of an enterprise, whichever is greater, if there has been an infringement of the following provisions: (Article 83, Paragraph 4[35])

- the basic principles for processing, including conditions for consent, pursuant to Articles 5, 6, 7, and 9

- the data subjects' rights pursuant to Articles 12 to 22

- the transfers of personal data to a recipient in a third country or an international organisation pursuant to Articles 44 to 49

- any obligations pursuant to member state law adopted under Chapter IX

- noncompliance with an order or a temporary or definitive limitation on processing or the suspension of data flows by the supervisory authority pursuant to Article 58(2) or failure to provide access in violation of Article 58(1)

B2B marketing

Within GDPR there is a distinct difference between B2C (business to consumer) and B2B (business to business) marketing. Under GDPR there are six grounds to process personal data, these are equally valid. There are two of these which are relevant to direct B2B marketing, they are consent or legitimate interest. Recital 47 of the GDPR states that “The processing of personal data for direct marketing purposes may be regarded as carried out for a legitimate interest.” [36]

Using legitimate interest as the basis for B2B marketing involves ensuring key conditions are met:

- “The processing must relate to the legitimate interests of your business or a specified third party, providing that the interests or fundamental rights of the data subject do not override the business’ legitimate interest."

- "The processing must be necessary to achieve the legitimate interests of the organisation.”[37]

Additionally, Article 6.1(f) of the GDPR states that the processing is lawful if it is: “Necessary for the purposes of the legitimate interests pursued by the controller or by a third-party, except where such interests are overridden by the interests or fundamental rights and freedoms of the individual which require protection of personal information, in particular where the individual is a child”[37]

The EU Commission stated that, “Unified data privacy laws will create extraordinary opportunities and motivating innovation for businesses not only within Europe but also for the organization who are willing to do business with European states.” The commission aims for companies to maintain communications and build regulation supporting relationships with each other to ensure best data practices through legitimate balance checks[38]

Restrictions

The following cases are not covered by the regulation:[14]

- Lawful interception, national security, military, police, justice

- Statistical and scientific analysis

- Deceased persons are subject to national legislation

- There is a dedicated law on employer-employee relationships

- Processing of personal data by a natural person in the course of a purely personal or household activity

Discussion and challenges

The proposal for the new regulation gave rise to much discussion and controversy.[39][40] Thousands of amendments were proposed.[41] The single set of rules and the removal of administrative requirements were both supposed to save money; however, as a May 2017 study conducted by Dimensional Research and TrustArc shows,[42] IT professionals expect that compliance with the GDPR will require additional investment overall: over 80 percent of those surveyed expected GDPR-related spending to be at least $100,000.[43] The concerns were echoed in a report commissioned by the law firm Baker & McKenzie that found that "around 70 percent of respondents believe that organizations will need to invest additional budget/effort to comply with the consent, data mapping and cross-border data transfer requirements under the GDPR."[44] The total cost for EU companies is estimated at around €200 billion while for US companies the estimate is for $41.7 billion. [45] Critics[who?] pointed to other issues as well.

- The requirement to have a data protection officer (DPO) is new for many EU countries and is criticised[by whom?] for its administrative burden.

- The GDPR was developed with a focus on social networks and cloud providers but did not consider enough requirements for handling employee data.[46][failed verification]

- Data portability is not seen as a key aspect for data protection but more a functional requirement for social networks and cloud providers although data portability creates transparency to evaluate privacy concerns of controllers.[citation needed]

- Although data minimisation is a requirement, with pseudonymisation being one of the possible means, the regulation provide no guidance on how or what constitutes an effective data de-identification scheme, with a grey area on what would be considered as inadequate pseudonymisation subject to Section 5 enforcement actions.[47][48][49]

- The protection against automated decisions in Article 22, brought forward from the Data Protection Directive's Article 15, has been claimed to provide protection against growing numbers of algorithmic decisions online and offline, including potentially a right to explanation. Whether the old provisions do provide any meaningful protection is a subject of ongoing debate.[23]

- Language and staffing challenges for the national data protection authorities (DPAs), as EU citizens no longer have a single DPA to contact for their concerns but have to deal with the DPA chosen by the company involved.

- Personal data cannot be transferred to countries outside the European Union unless they guarantee the same level of data protection.[50][failed verification]

- There is concern regarding the implementation of the GDPR in blockchain systems, as the transparent and fixed record of blockchain transactions contradicts the very nature of the GDPR.[51]

- The biggest challenges might be in the implementation of the GDPR:

- The implementation of the GDPR will require comprehensive changes to business practices for companies that had not implemented a comparable level of privacy before the regulation entered into force, especially non-European companies handling EU personal data.[citation needed]

- There is already a lack of privacy experts and knowledge and so new requirements might worsen the situation. Therefore, education in data protection and privacy legislation, particularly to keep in compliance with new rules as they arise, will be a critical factor for the success of the GDPR.[52] "Privacy by Design" and related topics were known to specialists only before the GDPR, and were mainly discussed in communities at law schools and in cryptography research. Recent university offerings just began to spread knowledge about designing for privacy from the legal, technological and managerial perspective, for example Karlstad university's free and open on-line course at master level.[53]

- The European Commission and DPAs must provide sufficient resources and power to enforce the implementation.

- A unique level of data protection has to be agreed upon by all European DPAs, as a different interpretation of the regulation might still lead to different levels of privacy.[citation needed]

- Europe's international trade policy is not yet in line with the GDPR.[54]

Timeline

- 25 January 2012: The proposal[13] for the GDPR was released.

- 21 October 2013: The European Parliament Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs (LIBE) had its orientation vote.

- 15 December 2015: Negotiations between the European Parliament, Council and Commission (Formal Trilogue meeting) resulted in a joint proposal.

- 17 December 2015: The European Parliament's LIBE Committee voted for the negotiations between the three parties.

- 8 April 2016: Adoption by the Council of the European Union.[55] The only member state voting against was Austria, which argued that the level of data protection in some respects falls short compared to the 1995 directive.[56][57]

- 14 April 2016: Adoption by the European Parliament.[58]

- 24 May 2016: The regulation entered into force, 20 days after its publication in the Official Journal of the European Union.[27]

- 25 May 2018: Its provisions will be directly applicable in all member states, two years after the regulations enter into force.[27]

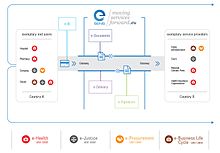

EU Digital Single Market

The EU Digital Single Market strategy aims to open up digital opportunities for people and business and enhance Europe's position as a world leader in the digital economy.[59] As part of the strategy, the GDPR and the NIS Directive will all apply from 25 May 2018. The proposed ePrivacy Regulation is also planned to be applicable from 25 May 2018. The eIDAS Regulation is also part of the strategy.

See also

References

- ^ Presidency of the Council: "Compromise text. Several partial general approaches have been instrumental in converging views in Council on the proposal for a General Data Protection Regulation in its entirety. The text on the Regulation which the Presidency submits for approval as a General Approach appears in annex," 201 pages, 11 June 2015, PDF, http://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-9565-2015-INIT/en/pdf

- ^ "GDPR Portal: Site Overview". General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- ^ "Art. 99 GDPR – Entry into force and application | General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)". General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- ^ "EUR-Lex - 31995L0046 - EN - EUR-Lex". eur-lex.europa.eu.

- ^ Blackmer, W.S. (5 May 2016). "GDPR: Getting Ready for the New EU General Data Protection Regulation". Information Law Group. InfoLawGroup LLP. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ "Inofficial [sic] consolidated version GDPR". Rapporteur Jan Philipp Albrecht. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- ^ a b Proposal for the EU General Data Protection Regulation. European Commission. 25 January 2012. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- ^ Article 3(2): This Regulation applies to the processing of personal data of data subjects who are in the Union by a controller or processor not established in the Union, where the processing activities are related to: (a) the offering of goods or services, irrespective of whether a payment of the data subject is required, to such data subjects in the Union; or (b) the monitoring of their behaviour as far as their behaviour takes place within the Union.

- ^ European Commission’s press release announcing the proposed comprehensive reform of data protection rules. 25 January 2012. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- ^ "EUR-Lex - 32016R0679 - EN - EUR-Lex". eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- ^ "Directive (EU) 2016/680 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data by competent authorities for the purposes of the prevention, investigation, detection or prosecution of criminal offences or the execution of criminal penalties, and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Council Framework Decision 2008/977/JHA". 4 May 2016.

- ^ The Proposed EU General Data Protection Regulation. A guide for in-house lawyers, Hunton & Williams LLP, June 2015, p. 14

- ^ a b "Data protection" (PDF). European Commission - European Commission.

- ^ a b "EUR-Lex - 32016R0679 - EN - EUR-Lex". eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 7 November 2017. Material has been copied from this source. Reuse of the EUR-Lex data for commercial or non-commercial purposes is authorised provided the source is acknowledged.

- ^ Regulation article 8 (1):"For the purposes of this Regulation, in relation to the offering of information society services directly to a child, the processing of personal data of a child below the age of 13 years shall only be lawful if and to the extent that consent is given or authorised by the child's parent or custodian."

- ^ "How the Proposed EU Data Protection Regulation Is Creating a Ripple Effect Worldwide". Judy Schmitt, Florian Stahl. 11 October 2012. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- ^ "How Smart Businesses Can Avoid GDPR Penalties When Recording Calls". www.xewave.io. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ^ "Privacy notices under the EU General Data Protection Regulation". ico.org.uk. 19 January 2018. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ^ "What information must be given to individuals whose data is collected?". European Commission - European Commission. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ^ editor, Ian Sample Science (27 January 2017). "AI watchdog needed to regulate automated decision-making, say experts". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ "EU's Right to Explanation: A Harmful Restriction on Artificial Intelligence". www.techzone360.com. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ^ Wachter, Sandra; Mittelstadt, Brent; Floridi, Luciano (28 December 2016). "Why a Right to Explanation of Automated Decision-Making Does Not Exist in the General Data Protection Regulation" – via SSRN.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Edwards, Lilian; Veale, Michael (2017). "Slave to the algorithm? Why a "right to an explanation" is probably not the remedy you are looking for". Duke Law and Technology Review. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2972855. SSRN 2972855. Material has been copied from this source. Reuse of the EUR-Lex data for commercial or non-commercial purposes is authorised provided the source is acknowledged.

- ^ "Privacy and Data Protection by Design — ENISA". www.enisa.europa.eu. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ Data science under GDPR with pseudonymization in the data pipeline Published by Dativa, 17 April, 2018

- ^ "Looking to comply with GDPR? Here's a primer on anonymization and pseudonymization". iapp.org.

- ^ a b c EU Official Journal issue L 119 "EU Journal". eur-lex.europa.eu.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Article 29 Working Party (2017). Guidelines on the right to data portability. European Commission.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Final European Union General Data Protection Regulation, by Cedric Burton, Laura De Boel, Christopher Kuner, Anna Pateraki, Sarah Cadiot and Sára G. Hoffman, Section II, 4". Bloomberg BNA. 12 February 2016.(Note that the Article 18 in the draft GDPR became Article 20 in the final version.)

- ^ Baldry, Tony; Hyams, Oliver. "The Right to Be Forgotten". 1 Essex Court.

- ^ "European Parliament legislative resolution of 12 March 2014 on the proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the protection of individuals with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data (General Data Protection Regulation)". European Parliament.

- ^ "REGULATION (EU) 2016/679 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL (article 30)".

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ "EUR-Lex – Art. 37". eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 23 January 2017. Material has been copied from this source. Reuse of the EUR-Lex data for commercial or non-commercial purposes is authorised provided the source is acknowledged.

- ^ "Guidelines on Data Protection Officers". Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- ^ a b "L_2016119EN.01000101.xml". eur-lex.europa.eu.

- ^ "What's new under the GDPR?". ico.org.uk. 22 March 2018.

- ^ a b https://dma.org.uk/uploads/misc/5aabd9a90feff-gdpr-essentials-for-marketers----an-introduction-to-the-gdpr_5aabd9a90fe17.pdf.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "How do we apply legitimate interests in practice?". ico.org.uk. 22 March 2018.

- ^ House of Commons Justice Committee (November 2012). The Committee's Opinion on the EU Data Protection Framework Proposals. House of Commons, U.K. p. 32. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

Another issue that has been subject to a large number of comments... is the requirement to appoint a DPO

- ^ Taylor Wessing (1 September 2016). "The compliance burden under the GDPR – Data Protection Officers". taylorweesing.com. Taylor Wessing. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

One of the politically most contentious innovations of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is the obligation to appoint a Data Protection Officer (DPO) in certain cases.

- ^ Overview of amendments. LobbyPlag. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ^ Dimensional Research (1 May 2017). "Privacy and the EU GDPR: 2017 Survey of Privacy Professionals" (PDF). TrustArc.com. TrustArc Inc. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ Babel, Chris (11 July 2017). "The High Costs of GDPR Compliance". Information Week. UBM Technology Group. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ Baker & McKenzie (4 May 2016). "PREPARING FOR NEW PRIVACY REGIMES: PRIVACY PROFESSIONALS' VIEWS ON THE GENERAL DATA PROTECTION REGULATION AND PRIVACY SHIELD" (PDF). bakermckenzie.com. Baker & McKenzie. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ Georgiev, Georgi. "GDPR Compliance Cost Calculator". GIGAcalculator.com. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ Expert tips: Get your business ready for GDPR. Regina Mühlich. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- ^ IAPP, Matt Wes, Apr 25 2017, Looking to comply with GDPR? Here's a primer on anonymization and pseudonymization.

- ^ Chassang, G. (2017). The impact of the EU general data protection regulation on scientific research. ecancermedicalscience, 11.

- ^ Tarhonen, Laura. (2017). Pseudonymisation of Personal Data According to the General Data Protection Regulation.

- ^ "Data transfers outside the EU". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ^ "A recent report issued by the Blockchain Association of Ireland has found there are many more questions than answers when it comes to GDPR". siliconrepublic.com. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- ^ "How to make the GDPR a success". www.privacytrust.com. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- ^ "Privacy by design | Karlstads universitet". www.kau.se (in Swedish). Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ "Irion, K., S. Yakovleva, M. Bartl: Trade and Privacy: Complicated Bedfellows? How to achieve data protection-proof free trade agreements". Institute for Information Law (IViR), University of Amsterdam. 22 September 2016.

- ^ "Data protection reform: Council adopts position at first reading - Consilium". www.consilium.europa.eu.

- ^ Adoption of the Council's position at first reading, Votewatch.eu

- ^ Written procedure, 8 April 2016, Council of the European Union

- ^ "Data protection reform - Parliament approves new rules fit for the digital era - News - European Parliament".

- ^ "Digital Single Market". Digital Single Market.

External links

- Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation)

- EU Data Protection page

- General Data Protection Regulation, final version dated 27 April 2016 (PDF)

- Multilingual HTML and PDF regulation documents, EUR-Lex

- Procedure 2012/0011/COD, EUR-Lex

- 2012/0011(COD) – Personal data protection: processing and free movement of data (General Data Protection Regulation), European Parliament