Papiermark

| Mark Template:De icon | |

|---|---|

100 trillion mark | |

| Unit | |

| Plural | Mark |

| Symbol | ℳ |

| Denominations | |

| Subunit | |

| 1/100 | Pfennig |

| Plural | |

| Pfennig | Pfennig |

| Symbol | |

| Pfennig | ₰ |

| Banknotes | 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 500 Mark 1, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200, 500 thousand Mark 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 500 million Mark 1, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200, 500 billion Mark 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100 trillion Mark |

| Coins | 1, 2, 5, 10, 50 Pfennig 1, 3, 200, 500 Mark |

| Demographics | |

| User(s) | |

| Issuance | |

| Central bank | Reichsbank |

The name (Template:Lang-en, officially just Mark, sign: ℳ) is applied to the German currency from 4 August 1914[1] when the link between the Goldmark and gold was abandoned, due to the outbreak of World War I. In particular, the name is used for the banknotes issued during the hyperinflation in Germany of 1922 and especially 1923.

History

From 1914, the value of the Mark fell. The rate of inflation rose following the end of World War I and reached its highest point in October 1923. The currency was stabilized in November 1923 after the announcement of the creation of the Rentenmark, although the Rentenmark did not come into circulation until 1924. When it did, it replaced the Papiermark at the rate of 1 trillion Papiermark = 1 Rentenmark. Later in 1924, the Rentenmark was replaced by the Reichsmark.

In addition to the issues of the government, emergency issues of both tokens and paper money, known as Kriegsgeld (war money) and Notgeld (emergency money), were produced by local authorities.

The Papiermark was also used in the Free City of Danzig until replaced by the Danzig Gulden in late 1923. Several coins and emergency issues in papiermark were issued by the free city.

Coins

During the war, cheaper metals were introduced for coins, including aluminium, zinc and iron, although silver ½ Mark pieces continued in production until 1919. Aluminium 1 Pfennig were produced until 1918 and the 2 Pfennig until 1916. Whilst iron 5 Pfennig, both iron and zinc 10 Pfennig and aluminium 50 Pfennig coins were issued until 1922. Aluminium 3 Mark were issued in 1922 and 1923, and aluminium 200 and 500 Mark were issued in 1923. The quality of many of these coins varied from decent to poor.

During this period, many provinces and cities also had their own corresponding coin and note issues, referred to as Notgeld currency. This came about often due to a shortage of exchangeable tender in one region or another during the war and hyperinflation periods. Some of the most memorable of these to be issued during this period came from Westfalen and featured the highest face value denominations on a coin ever, eventually reaching 50,000,000 Mark.

Banknotes

First World War issues

In 1914, the State Loan Office began issuing paper money known as Darlehnskassenscheine (loan fund notes). These circulated alongside the issues of the Reichsbank. Most were 1- and 2-Mark notes but there were also 5-, 20-, 50- and 100-Mark notes.

Post War issues

The victor nations in World War I decided to assess Germany for their costs of conducting the war against Germany. With no means of paying in gold or currency backed by reserves, Germany ran the presses, causing the value of the Mark to collapse.[disputed – discuss] Many Germans literally carted wheelbarrows of cash to pay for groceries.[citation needed]

Between 1914 and the end of 1923 the German papiermark’s rate of exchange against the U.S. dollar plummeted from 4.2 mark/dollar to 4.2 trillion mark/dollar.[2] The price of one gold mark (0.35842g gold weight) in German paper currency at the end of 1918 was two paper mark, but by the end of 1919 a gold mark cost 10 paper mark.[3] This inflation worsened between 1920 and 1922, and the cost of a gold mark (or conversely the devaluation of the paper mark) rose from 15 to 1,282 paper mark.[3] In 1923 the value of the paper mark had its worst decline. By July, the cost of a gold mark had risen to 101,112 paper mark, and in September was already at 13 million.[3] On 30 Nov 1923 it cost 1 trillion paper mark to buy a single gold mark.[3]

In October 1923, Germany experienced a 29,500% hyperinflation (roughly 21% interest per day).[4] Historically, this one-month inflation rate has only been exceeded three times: Yugoslavia, 313,000,000% (64.6% per day, January 1994); Zimbabwe, 79.6 billion% (98% per day, November 2008); and Hungary, 41.9 quadrillion% (207% per day, July 1946).[4]

On 15 November 1923 the papiermark was replaced by the rentenmark at 4.2 rentenmark/dollar,[2] or 1 trillion papiermark/rentenmark (exchangeable through July 1925).[5]

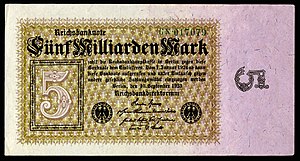

During the hyperinflation, ever higher denominations of banknotes were issued by the Reichsbank[6] and other institutions (notably the Reichsbahn railway company).[7] The Papiermark was produced and circulated in enormously large quantities. Before the war, the highest denomination was 1000-Mark, equivalent to approximately 50 British pounds or 238 US dollars. In early 1922, 10,000-Mark notes were introduced, followed by 100,000- and 1 million-Mark notes in February 1923. July 1923 saw notes up to 50 million-Mark, with 10 milliard (1010)-Mark notes introduced in September. The hyperinflation peaked in October 1923 and banknote denominations rose to 100 trillion (1014)-Mark. At the end of the hyperinflation, these notes were worth approximately £5 sterling or US$24.

German Papiermark of the Weimar Republic (1920–24)

| Year | Issue | Value[nb 1] | Date[nb 2] | Image | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First[8] | 10 | 6 Feb 1920 | 126 mm × 84 mm (5.0 in × 3.3 in) | ||

| 50 | 23 Jul 1920 | 150 mm × 100 mm (5.9 in × 3.9 in) | |||

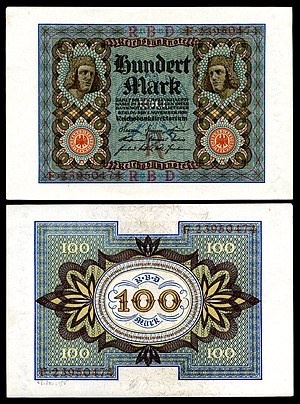

| 100 | 1 Nov 1920 | Portraits based on the Bamberg riders at Bamberg Cathedral 162 mm × 108 mm (6.4 in × 4.3 in) | |||

| First[9] | 10,000 | 19 Jan 1922 | Bildnis Eines Jungen Mannes by Albrecht Dürer 210 mm × 124 mm (8.3 in × 4.9 in) | ||

| Second[10] | 500 | 27 Mar 1922 | Jakob Meyer of the Meyer zum Pfeil family. 175 mm × 112 mm (6.9 in × 4.4 in) | ||

| 500 | 7 Jul 1922 | 173 mm × 90 mm (6.8 in × 3.5 in) | |||

| Third[10] | 100 | 4 Aug 1922 | 162 mm × 90 mm (6.4 in × 3.5 in) | ||

| 1,000 | 15 Sep 1922 | 160 mm × 85 mm (6.3 in × 3.3 in) | |||

| 5,000 | 16 Sep 1922 | Section of Portrait of a Man with a Coin by Hans Memling 130 mm × 90 mm (5.1 in × 3.5 in) | |||

| 5,000 | 19 Nov 1922 | Portrait of Hans Urmiller based on Hans Urmiller und Sohn by Barthel Beham 198 mm × 107 mm (7.8 in × 4.2 in) | |||

| 50,000 | 19 Nov 1922 | Bürgermeister Arnold von Brauweiler based on Burgomaster Arnold von Brauweiler by Barthel Bruyn the Elder 190 mm × 110 mm (7.5 in × 4.3 in) | |||

| Fourth[10] | 5,000 | 2 Dec 1922 | Merchant Imhof based on Bildnis eines unbekannten Mannes by Albrecht Dürer 130 mm × 90 mm (5.1 in × 3.5 in) | ||

| Fifth[11] | 1,000 | 15 Dec 1922 | Portrait of Jörg Herz based on Jörg Herz Nürnberger Münzmeister by Georg Pencz 140 mm × 90 mm (5.5 in × 3.5 in) | ||

| First[11] | 100,000 | 1 Feb 1923 | Merchant Georg Giese based on Der Kaufmann Georg Gisze by Hans Holbein the Younger 190 mm × 115 mm (7.5 in × 4.5 in) | ||

| Second[11] | 10,000 | 3 Feb 1923 | Not issued | ||

| 20,000 | 20 Feb 1923 | 160 mm × 95 mm (6.3 in × 3.7 in) | |||

| 1 million | 20 Feb 1923 | 160 mm × 110 mm (6.3 in × 4.3 in) | |||

| Third[12] | 5,000 | 15 Mar 1923 | Portrait of Hans Urmiller based on Hans Urmiller und Sohn by Barthel Beham 148 mm × 90 mm (5.8 in × 3.5 in) | ||

| 500,000 | 1 May 1923 | 170 mm × 95 mm (6.7 in × 3.7 in) | |||

| 2 million | 23 Jul 1923 | Merchant Georg Giese based on Der Kaufmann Georg Gisze by Hans Holbein the Younger 162 mm × 87 mm (6.4 in × 3.4 in) | |||

| 5 million | 1 Jun 1923 | 170 mm × 95 mm (6.7 in × 3.7 in) | |||

| Fourth[13] | 100,000 | 25 Jul 1923 | 110 mm × 80 mm (4.3 in × 3.1 in) | ||

| 500,000 | 25 Jul 1923 | 175 mm × 80 mm (6.9 in × 3.1 in) | |||

| 1 million | 25 Jul 1923 | 160 mm × 95 mm (6.3 in × 3.7 in) | |||

| 1 million | 25 Jul 1923 | 185 mm × 80 mm (7.3 in × 3.1 in) | |||

| 5 million | 25 Jul 1923 | 190 mm × 80 mm (7.5 in × 3.1 in) | |||

| 10 million | 25 Jul 1923 | 195 mm × 80 mm (7.7 in × 3.1 in) | |||

| 20 million | 25 Jul 1923 | 195 mm × 83 mm (7.7 in × 3.3 in) | |||

| 50 million | 25 Jul 1923 | 195 mm × 86 mm (7.7 in × 3.4 in) | |||

| Fifth[14] | 50,000 | 9 Aug 1923 | 105 mm × 70 mm (4.1 in × 2.8 in) | ||

| 200,000 | 9 Aug 1923 | 115 mm × 70 mm (4.5 in × 2.8 in) | |||

| 1 million | 9 Aug 1923 | 120 mm × 80 mm (4.7 in × 3.1 in) | |||

| 2 million | 9 Aug 1923 | 125 mm × 80 mm (4.9 in × 3.1 in) | |||

| 5 million | 20 Aug 1923 | 128 mm × 80 mm (5.0 in × 3.1 in) | |||

| 10 million | 22 Aug 1923 | 125 mm × 80 mm (4.9 in × 3.1 in) | |||

| 100 million | 22 Aug 1923 | 150 mm × 85 mm (5.9 in × 3.3 in) | |||

| Sixth[15] | 20 million | 1 Sep 1923 | 125 mm × 82 mm (4.9 in × 3.2 in) | ||

| 50 million | 1 Sep 1923 | 124 mm × 84 mm (4.9 in × 3.3 in) | |||

| 500 million | 1 Sep 1923 | 155 mm × 85 mm (6.1 in × 3.3 in) | |||

| 500 billion | 1 Sep 1923 | Specimen only | |||

| 1 trillion | 1 Sep 1923 | Specimen only | |||

| Seventh[15] | 1 billion | 5 Sep 1923 | Overprinted on 15 Dec 1922 note 140 mm × 90 mm (5.5 in × 3.5 in) | ||

| 1 billion | 5 Sep 1923 | 160 mm × 86 mm (6.3 in × 3.4 in) | |||

| 5 billion | 10 Sep 1923 | 165 mm × 85 mm (6.5 in × 3.3 in) | |||

| 10 billion | 15 Sep 1923 | ||||

| 10 billion | 1 Oct 1923 | 160 mm × 105 mm (6.3 in × 4.1 in) | |||

| 20 billion | 1 Oct 1923 | 140 mm × 90 mm (5.5 in × 3.5 in) | |||

| 50 billion | 10 Oct 1923 | 176 mm × 86 mm (6.9 in × 3.4 in) | |||

| 200 billion | 15 Oct 1923 | 140 mm × 80 mm (5.5 in × 3.1 in) | |||

| Eighth[16] | 1 billion | 20 Oct 1923 | 127 mm × 61 mm (5.0 in × 2.4 in) | ||

| 5 billion | 20 Oct 1923 | 130 mm × 64 mm (5.1 in × 2.5 in) | |||

| 500 billion | 20 Oct 1923 | Overprinted on 15 Mar 1923 note Portrait of Hans Urmiller based on Hans Urmiller und Sohn by Barthel Beham 145 mm × 90 mm (5.7 in × 3.5 in) | |||

| Ninth[16] | 50 billion | 26 Oct 1923 | 135 mm × 65 mm (5.3 in × 2.6 in) | ||

| 100 billion | 26 Oct 1923 | 135 mm × 65 mm (5.3 in × 2.6 in) | |||

| 500 billion | 26 Oct 1923 | 137 mm × 65 mm (5.4 in × 2.6 in) | |||

| 100 trillion | 26 Oct 1923 | 174 mm × 86 mm (6.9 in × 3.4 in) | |||

| Tenth[17] | 1 trillion | 1 Nov 1923 | 137 mm × 65 mm (5.4 in × 2.6 in) | ||

| 5 trillion | 1 Nov 1923 | 168 mm × 86 mm (6.6 in × 3.4 in) | |||

| 10 trillion | 1 Nov 1923 | 171 mm × 86 mm (6.7 in × 3.4 in) | |||

| 10 trillion | 1 Nov 1923 | 120 mm × 82 mm (4.7 in × 3.2 in) | |||

| Eleventh[18] | 100 billion | 5 Nov 1923 | 135 mm × 65 mm (5.3 in × 2.6 in) | ||

| 1 trillion | 5 Nov 1923 | 143 mm × 86 mm (5.6 in × 3.4 in) | |||

| 2 trillion | 5 Nov 1923 | 120 mm × 71 mm (4.7 in × 2.8 in) | |||

| 5 trillion | 7 Nov 1923 | 165 mm × 86 mm (6.5 in × 3.4 in) | |||

| First[18] | 10 trillion | 1 Feb 1924 | 140 mm × 72 mm (5.5 in × 2.8 in) | ||

| 20 trillion | 5 Feb 1924 | Portrait of a woman based on Bildnis einer jungen Venezianerin by Albrecht Dürer 160 mm × 95 mm (6.3 in × 3.7 in) | |||

| 50 trillion | 10 Feb 1924 | Jakob Muffel based on Portrait of Jakob Muffel by Albrecht Dürer 175 mm × 95 mm (6.9 in × 3.7 in) | |||

| 100 trillion | 15 Feb 1924 | Portrait of Willibald Pirckheimer based on a painting by Albrecht Dürer 180 mm × 95 mm (7.1 in × 3.7 in) | |||

| Second[19] | 5 trillion | 15 Mar 1924 | 120 mm × 72 mm (4.7 in × 2.8 in) |

German Papiermark of Danzig

The Danziger Privat Actien-Bank (opened 1856) was the first bank established in Danzig.[20] They issued two series of notes denominated in thalers (1857 and 1862–73) prior to issuing the mark (1875, 1882, 1887).[21] These mark issues are extremely rare.[21] The Ostbank fur Handel and Gewerbe opened 16 March 1857, and by 1911 two additional banks (the Imperial Bank of Germany and the Norddeutsche Credit-Anstalt) were in operation.[22]

Issuance of the Danzig papiermark

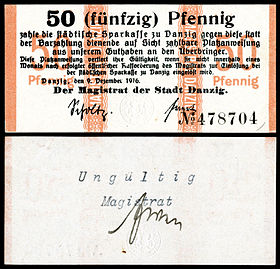

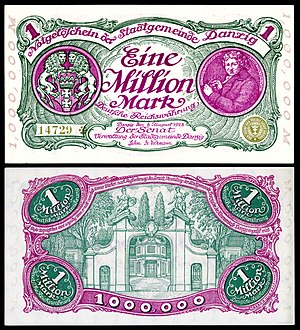

The German papiermark was issued by Danzig from 1914 to 1923.[23] Five series were issued during World War I by the City Council (1914, 1916, 1918 first and second issue, and 1919).[24] Denominations ranged from 10 pfennig to 20 mark.[24] The Free City of Danzig municipal senate issued an additional four post-World War I series of notes (1922, 1923 First issue, 1923 Provisional issue, and 1923 Inflation issue).[25] The 1922 issue (31 October 1922) was denominated in 100, 500, and 1000 mark notes.[26] The denominations for the 1923 issue were 1000 (15 March 1923), and 10000 and 50000 mark notes (20 March 1923).[27] The 1923 provisional issue reused earlier notes with a large red stamp indicating the new (and higher) denominations of 1 million (8 August 1923) and 5 million (15 October 1923) mark.[28] The last series of Danzig mark was the 1923 inflation issue of 1 million (8 August 1923), 10 million (31 August 1923), 100 million (22 September 1923), 500 million (26 September 1923), and 5 billion mark notes (11 October 1923).[29] The Danzig mark was replaced by the Danzig gulden, first issued by the Danzig Central Finance Department on 22 October 1923.[29]

| Issue | Value | Image |

|---|---|---|

| 50 Pfennig | ||

| 1 Mark | ||

| 2 Mark | ||

| 3 Mark | ||

| 10 Pfennig | ||

| 50 Pfennig | ||

| 5 Mark | ||

| 20 Mark | ||

| 50 Pfennig | ||

| 20 Mark | ||

| 50 Pfennig | ||

| 100 | ||

| 500 | ||

| 1,000 | ||

| 1,000 | ||

| 10,000 | ||

| 50,000 | ||

| 1 million | ||

| 5 million | ||

| 1 million | ||

| 10 million | ||

| 100 million | ||

| 500 million | ||

| 5 billion | ||

| 10 billion |

Note on numeration

In German, Milliarde is 1,000,000,000, or one thousand million, while Billion is 1,000,000,000,000, or one million million.

See also

Footnotes

- ^ All values are in Reichsbank Mark.

- ^ Series date printed on the banknote.

Notes

- ^ Knapp, George Friedrich (1924), The State Theory of Money, Macmillan and Company, pp. vxi

- ^ a b Barisheff 2013, p. 32.

- ^ a b c d Fischer 2010, p. 85.

- ^ a b Fischer 2010, p. 91.

- ^ Widdig 2001, p. 48.

- ^ Cuhaj 2010, pp. 555–64.

- ^ Cuhaj 2009, pp. 629–36.

- ^ Cuhaj 2010, pp. 555–56.

- ^ Cuhaj 2010, pp. 556.

- ^ a b c Cuhaj 2010, pp. 557.

- ^ a b c Cuhaj 2010, pp. 558.

- ^ Cuhaj 2010, pp. 558–59.

- ^ Cuhaj 2010, pp. 559.

- ^ Cuhaj 2010, pp. 560–61.

- ^ a b Cuhaj 2010, pp. 561–62.

- ^ a b Cuhaj 2010, pp. 562.

- ^ Cuhaj 2010, pp. 562–63.

- ^ a b Cuhaj 2010, pp. 563.

- ^ Cuhaj 2010, pp. 563–64.

- ^ Kelly 1920, p. 30.

- ^ a b Cuhaj 2009, p. 613.

- ^ Rand McNally 1911, p. 972.

- ^ Cuhaj 2010, pp. 427–30.

- ^ a b Cuhaj 2010, pp. 427–28.

- ^ Cuhaj 2010, pp. 428–30.

- ^ Cuhaj 2010, pp. 428.

- ^ Cuhaj 2010, pp. 429.

- ^ Cuhaj 2010, pp. 429–30.

- ^ a b Cuhaj 2010, pp. 430.

References

- Barisheff, Nick (2013). $10,000 Gold – Why Gold’s Inevitable Rise is the Investor’s Safe Haven. John Wiley & Sons Canada, Ltd. ISBN 978-1-118-44350-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cuhaj, George S., ed. (2009). Standard Catalog of World Paper Money Specialized Issues (11 ed.). Krause. ISBN 978-1-4402-0450-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cuhaj, George S., ed. (2010). Standard Catalog of World Paper Money General Issues (1368-1960) (13 ed.). Krause. ISBN 978-1-4402-1293-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fischer, Wolfgang C., ed. (2010). German Hyperinflation 1922/23: A Law and Eonomics Approach. Josef Eul Verlag GmbH. ISBN 978-3-89936-931-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - GermanNotes.com (2005). German Paper Money 1871-1999. eBook from germannotes.com[dead link]

- Kelly, William J. (1920). "The Situation at Danzig". Journal of the American-Polish Chamber of Commerce and Industry. 1 (6). American-Polish Chamber of Commerce and Industry.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Krause, Chester L.; Clifford Mishler (1991). Standard Catalog of World Coins: 1801–1991 (18th ed.). Krause Publications. ISBN 0873411501.

- Pick, Albert (1994). Standard Catalog of World Paper Money: General Issues. Colin R. Bruce II and Neil Shafer (editors) (7th ed.). Krause Publications. ISBN 0-87341-207-9.

- Rand McNally (1911). "The Rand-McNally Banker's Director and List of Attorneys". Rand McNally International Bankers Directory. 70 (1). Rand McNally & Company.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Widdig, Bernd (2001). Culture and Inflation in Weimar Germany. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22290-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

| Preceded by: Goldmark |

Currency of Germany 1914 – 1923 |

Succeeded by: Rentenmark Reason: inflation Ratio: 1 Rentenmark = 1,000,000,000 Papiermark, and 4.2 Rentenmark = US$1 |