Giyorgis of Segla

Giyorgis of Segla | |

|---|---|

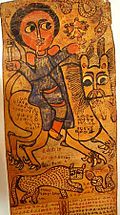

Late 17th century portrait of Giyorgis of Segla by Baselyos | |

| Nebura'ed (abbot) of Debre Damo | |

| Born | c. 1365 |

| Residence | Ethiopian Empire |

| Died | 1 July 1425 (aged 59–60) |

| Venerated in | Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church |

| Feast | 14 July[1] |

| Controversy | Sabbath in Christianity |

| Major works | Hours and Book of Mystery |

| Part of a series on |

| Oriental Orthodoxy |

|---|

|

| Oriental Orthodox churches |

|

|

Giyorgis of Segla (c. 1365 – 1 July 1425[a]), also known as Giyorgis of Gasicha or Abba Giyorgis,[b][1][6] was an Ethiopian Oriental Orthodox monk, saint,[7] and author of religious books.

Giyorgis' work has had great influence on Ethiopian monastic calendars, hymns and Ge'ez literature. He is considered one of the most important Ge'ez writers in fifteenth-century Ethiopia.

Giyorgis was involved in a controversy concerning Sabbath in Christianity and consequentially fell into disfavor of emperor Dawit I. He managed to continue his work later in life, under the reigns of Tewodros I and Yeshaq I.

Disputed identity

[edit]It is possible that two or three prominent religious figures have been mixed into the same figure in Ethiopian Church tradition, and Giyorgis' identity remains uncertain. One theory is that Abba Giyorgis of Dabra Bahrey and Giyorgis of Segla (or Gasicha) are separate persons who lived in the mid-14th century. Abba Giyorgis of Dabra Bahrey may have flourished during the reign of emperor Amda Seyon I (1314–1344). He would have been the disciple of saint Iyasus Mo'a at the monastery of Hayq. Giyorgis of Segla (died between 1424 and 1426) would have been the writer, the preacher and the musician. A single remaining copy of his Gadl is being kept in the monastery of Hayq.[1] Gadl (Saint's Life) is a traditional form of Ge'ez hagiography written by disciples of the saints after their demise.[8]

Early life

[edit]

Giyorgis' parents were of noble descent.[1] Giyorgis' father was Hezba Tseyon, a court chaplain of emperor Dawit I. His father was known by his contemporaries as "a comprehender of the Scriptures like Salathiel" (Salathiel refers to Ezra the Scribe). His mother was Emmena Seyon from Bete Amhara.[1][9][6] Giyorgis is among the monks who are claimed to have been students of Ethiopian saint and monastic leader Iyasus Mo'a at Lake Hayq's prominent monastery,[10][11] which had become a place of pilgrimage already during Iyasus Mo'a's lifetime.[12] The beginning of Giyorgis' career was not without hardship. He was so slow in learning that his teacher had lost hope at one point. Ethiopian education of the time relied heavily on memorization, and without showing ability one would not get very far in studies where knowledge was preserved orally. It has been told that:[1]

Faced with this problem, Giyorgis went daily to church, where he prayed with tears and total concentration to God and the Blessed Virgin. One night, the Blessed Virgin appeared to him and told him to be diligent in his learning, forgoing even sleeping by night.[1]

Career

[edit]

Giyorgis was among the most important (theological) authors in Ge'ez language during the fifteenth century in medieval Ethiopia.[4][13][14][15] His stature can be compared to those of emperor Zara Yaqob and a pseudonymous author known only by the name Ritu'a Haymanot ("The One with the Orthodox Faith").[15] Out of his writing, Giyorgis is mostly remembered for his book of hours, known simply as Hours (Sa'atat), and The Book of Mystery (Masehafa mestir). Before his work on calendars, the Ge'ez version of the Coptic Book of Hours was a widely used book, even though many monasteries opted to compile their own books of hours. Use of the Coptic Book of Hours prevailed to some extent, despite Giyorgis' book being the most prevalent book in use.[1] His book was gradually expanded to include additional material, such as hymns, during the century following from its inception.[16] A late 17th-century Ethiopian book from Gondar, the Miracles of Mary (Te'amire Maryam),[17] includes a story how Virgin Mary favored Giyorgis' book of hours.[5]

Giyorgis had risen into a position of court chaplain during emperor Dawit I's reign like his father had before him.[6] Royal princes were tutored by him in the court.[6][2] Notably Giyorgis' student and future emperor Zara Yaqob held very similar theological views throughout his life.[18] Giyorgis' thoughts concerning the Sabbath, however, got him into trouble with other churchmen and Dawit I, who imprisoned him.[6][1] Disputes about the Sabbath were politically destabilizing, and the realm was troubled with monastic infighting during the 15th century.[19] Ethiopia of that time had much contact with the outside world, which brought many missionaries of competing traditions and other travelers into the country. The Miaphysite Church and monastic leaders found themselves occasionally at odds with foreigners who managed to influence political leaders. A foreigner called Bitu, who had wielded great influence on the emperor, was involved in a decision to imprison Giyorgis. There were differences in religious views between Bitu and Giyorgis, as shown in the Book of Mystery where Giyorgis devotes a chapter to refute Bitu's views on the Image of God.[1] He was finally released[1] when one of his former royal students, Tewodros I, rose to the throne. Despite his dissidence, he continued to hold influence until his death during the reign of emperor Yeshaq I.[6] While Giyorgis had wished to join a monastery of Dabra Libanos, disputes about the Sabbath led him to join Dabra Gol in historical Wollo region instead.[6][1] There, late in his life, he became the head of the community of Abba Batsalota-Mikael.[6][1] Many of his former royal students, who were the eight sons of emperor Dawit I, one by one became rulers of the Ethiopian Empire.[2][6][1]

Giyorgis writes in his Book of Mystery that man is a creature of God with an immortal soul. With the divine gift of soul, man becomes different from other creatures, as man is an intelligent and speaking thing. Giyorgis' view of man can be characterized as dualistic.[20] With the book, Giyorgis also attempted to refute heretical beliefs. It is an extensive anti-heretical work composed of 30 chapters. Treatises on heresy are meant to be read during important feast days of the Ethiopian Church. Each treatise concentrates on a different heretical doctrine, and the book refutes them one by one. The book was completed on 21 June 1424. It is the most important original Ethiopian theological work.[20][1] The book is still used in liturgy.[1]

At one point, Giyorgis held the position of abbot (Nebura'ed) of the important monastery of Debre Damo.[1][6][9][21] He also founded the monastery of Debre Bahriy in Gasicha.[15] At the monastery named after him, there is a crosscut in warka tree's bark claimed to have been left behind by Giyorgis himself.[22]

Hymnody

[edit]

In addition to being a renowned author of religious books, Giyorgis also composed hymns,[23] such as ones in honor of Saint Peter and Saint Paul.[5] He authored a collection of hymns that competed with other hymnals of the time for recognition as the hymnal of the Ethiopian Church's saints, and its contents leaned towards viewpoints of the Roman Catholic Church at a remarkably early date. Emperor Zara Yaqob's hymnal, however, was the most successful one.[24] Under Giyorgis' leadership, scholars from Debre Negudgad and Debre-Egziabiher separated hymns of the fasting season into their own section. This was an innovation compared to the traditional division of Saint Yared's 6th century hymnals (degua) which featured only three divisions.[25] The full extent of Giyorgis' compositions is unknown, and various local anaphoras of the Divine Liturgy may have been originally composed by him.[1]

Views on the Sabbath

[edit]Giyorgis sought to justify Christian observation of the Sabbath on Sunday based on Old Testament scripture.[26]

As is customary in Christianity, Giyorgis held that Jesus had established Sunday as the Lord's Day. But Giyorgis went further than that. He reasoned that if Jesus had come to fulfill the Mosaic Law, then one would expect to find hints of the Sunday Sabbath in the Pentateuch.[26] He sought to do this by presenting mathematical proof based on the calendar found in the Book of Jubilees and the similar Enoch calendar in the Book of Enoch. The features of these calendars are a 364-day-year,[27] a seven-year cycle culminating in the Jubilee (year of the release),[28] and a particular arrangement of biblical Jewish holidays.[27] Giyorgis sought to demonstrate that Sunday corresponds to the Jubilee year,[28] the "Sabbath's Sabbath".[29]

Relying on the authority of the Jubilee and Enoch calendars was possible because both the Book of Jubilees and Enoch are part of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church's Biblical canon.[27] The Church, however, had already long before switched to the 365-day Ethiopian calendar (based on the Julian calendar). In effect, this meant that Giyorgis' calculation would have no practical impact on the liturgical year of the Church.[30]

Giyorgis lays out his idea in the following passage of his Sermon on the First Sabbath:[31]

And in substitution of the number of the days of the year of release the Lord gave the commemoration of His resurrection, that is the first of the Sabbath [= μία τῶν σαββάτων]. And the number of the days of the year of release is 364. And the fifth one is the shifting day that rolls around the days of the years and revolves them, from this to that, and from the second to the third, and, at the fourth year, catches up [lit. becomes equal] – due to the birth of the light after 30 days after the creation of the world – with the 30th hour of the fourth day after the birth of the ṭəntəyon. And because the number of the first days [= Sundays] of the seven years is 364, and because (the fifth day) shifted them when catching up [lit. becoming equal], it [sc., the day of resurrection = Sunday] remained hidden in the bosom of the Scripture, and its greatness has not been revealed until the commemoration of the resurrection. And, for the commemoration of the resurrection, we have left the year of release and accepted the commemoration of the resurrection that is the first [of the Sabbath = Sunday], because with the reckoning of the days of the year of release he [sc. the Lord] reckoned the first [after the Sabbath] days [= Sundays] of the six years.[32]

This can be summarized as:

At the first year of the four-year cycle, the beginning of the year falls on Wednesday. Then, at the second and the third years, it moves by one day forward, that is, from Wednesday to Thursday and from Thursday to Friday. The next, fourth year is the bissextile one. This year, the shift is not of one but of two weekdays. Thus, this day falls on Sunday. For Abba Giyorgis, however, there is no Sunday as a separate day but rather a part of the 49-hour Sabbath. Therefore, he continues counting of the hours of the Sabbath after the number 24. The 30th hour of Sabbath ("the fourth day after the birth of ṭəntəyon") is Sunday midnight, the approximate time of Christ's resurrection.[33]

Works

[edit]- Book of Hours [for the Daytime] (Sa'atat)[34][35]

- Book of Hymns[6]

- Book of Mystery (Masehafa Mestir, completed on 21 June 1424)[20][6]

- Book of Thanks (also known as Book of Light)[6]

- Horologium of the Night Hours (Sa'atat Zelelit)[34]

- Hymns of Praise (Enzira Sebhat)[6]

- Praises of the Cross[36][6]

- Arganonä Maryam (The Organ of mary)[citation needed]

- Saqoqāwa dǝngǝl (Lament of the Virgin)[citation needed]

- Fékkare haymanot (Synopsis of the Faith)[citation needed]

- Hohétä Bérhan (The Gate of Light)[citation needed]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Getatchew Haile (1991). Ethiopian Saints: Claremont Coptic Encyclopedia. Vol. 2. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- ^ a b c Seife, Daniel; Feleke, Michael (2015). "SAINT ABBA GIORGIES OF GASSICHA THE ETHIOPIAN THEOLOGIAN". Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- ^ a b "Giyorgis Abā". WorldCat. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- ^ a b Getatchew Haile (2009). "A Miracle of the Archangel Uriel Worked for Abba Giyorgis of Gasǝč̣č̣a" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 February 2017. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- ^ a b c Marilyn Eiseman Heldman; Frē Ṣeyon (1994). The Marian Icons of the Painter Frē Ṣeyon: A Study of Fifteenth-century Ethiopian Art, Patronage, and Spirituality. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 75. ISBN 978-3-447-03540-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Tsehai Berhane Selassie (1997). "Giyorgis, Abba, Ethiopia, Orthodox". The Encyclopaedia Africana – Dictionary of African Biography. Vol. 1. L. H. Ofosu-Appiah, editor-in-chief. ISBN 9780917256011. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- ^ "The Social and religious functions of the Eucharist in Medieval Ethiopia". Annales d'Ethiopie. 19 (1): 15. 2003.

- ^ "Lives of Ethiopian Saints". Link Ethiopia. Archived from the original on 5 March 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- ^ a b Munro-Hay, Stuart (2005). "Saintly Shadows". In Raunig, Walter; Wenig, Steffen (eds.). Afrikas Horn. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 156. ISBN 978-3-447-05175-0.

- ^ G. W. B. Huntingford. "GIYORGIS, Ethiopia, Orthodox". The Dictionary of Ethiopian Biography, Vol. 1. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- ^ Emmanuel Kwaku Akyeampong; Henry Louis Gates (2012). Dictionary of African Biography. OUP USA. pp. 175–176. ISBN 978-0-19-538207-5.

- ^ Nigus, Kassa (7 December 2015). "Mahibere Kidusan – The Short Biography of Abba Iyyesus Moa". Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- ^ Johnston, William M. (4 December 2013). Encyclopedia of Monasticism. Routledge. p. 517. ISBN 978-1-136-78716-4.

- ^ Uhlig, Siegbert (2006). Proceedings of the XVth International Conference of Ethiopian Studies, Hamburg, July 20–25, 2003. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 536. ISBN 978-3-447-04799-9.

- ^ a b c Getatchew Haile (January 2013). "The Southern Shores of the Mediterranean and Beyond: The Case Ethiopian Manuscript Heritage" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 August 2017.

- ^ Sergew Hable Sellassie; Belaynesh Mikael (2003). "Worship In The Ethiopian Orthodox Church". Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- ^ "Miracles of Mary (Te'amire Maryam)". Art Institute of Chicago. 2013. Archived from the original on 18 May 2018. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- ^ Hastings 1995, p. 34.

- ^ Hastings 1995, p. 36.

- ^ a b c Kidane Dawit Worku (2012). The Ethics of Zär'a Ya'eqob: A reply to the historical and religious violence in the seventeenth century Ethiopia. Gregorian Biblical BookShop. pp. 166–167. ISBN 978-88-7839-222-9.

- ^ Hastings 1995, p. 37.

- ^ Wright, St. (1957). "Notes on some Cave Churches in the Province of Wallo". Annales d'Ethiopie. 2 (1): 7–13. doi:10.3406/ethio.1957.1255.

- ^ Teresa Berger; Bryan D. Spinks (1 December 2009). The Spirit in Worship-Worship in the Spirit. Liturgical Press. p. 315. ISBN 978-0-8146-6234-2.

- ^ Irvine, A. K. (1 June 1985). "Haile Getatchew: The different collections of nägś hymns in Ethiopic literature and their contributions. (Oikonomia. Quellen und Studien zur Orthodoxen Theologie, Bd. 19.) [viii], [104] PP. Erlangen: Lehrstuhl für Geschichte und Theologie des christlichen Ostens, 1983". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 48 (2): 364. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00033632. S2CID 177283389.

- ^ Tsegaye, Mezmur (June 2011). "Traditional Education of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and Its Potential for Tourism Development (1975–present)". www.academia.edu: 22–23.

- ^ a b Lourié 2016, p. 74.

- ^ a b c Lourié 2016, p. 82.

- ^ a b Lourié 2016, p. 79.

- ^ Neville, David (2002). Prophecy and Passion: Essays in Honour of Athol Gill. ATF Press. p. 284. ISBN 978-1-920691-00-4.

- ^ Lourié 2016, p. 83.

- ^ Lourié 2016, p. 75.

- ^ Lourié 2016, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Lourié 2016, p. 80.

- ^ a b "Project search". Endangered Archives Programme. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- ^ Steve Delamarter; Getatchew Haile (31 January 2013). Catalogue of the Ethiopic Manuscript Imaging Project: Codices 106–200 and Magic Scrolls 135–284. Casemate Publishers. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-227-17384-8.

- ^ Haile, Getatchew (18 April 2013). "Praises of the Cross, Wǝddase Mäsqäl, by Abba Giyorgis of Gasǝč̣č̣a". Aethiopica. 14 (1): 47–120. doi:10.15460/aethiopica.14.1.414.

Sources

[edit]- Hastings, Adrian (5 January 1995). "The Policies of Zara Ya'iqob". The Church in Africa, 1450-1950. Clarendon Press. pp. 34–37. ISBN 978-0-19-152055-6.

- Lourié, Basil (2016). "An Archaic Jewish-Christian Liturgical Calendar in Abba Giyorgis of Sägla". Scrinium. 12 (1): 73–83. doi:10.1163/18177565-00121p07. ISSN 1817-7530.

Further reading

[edit]- —. "Julianism". Encyclopaedia Aethiopica (EAE). Vol. 3. pp. 308–310.

- Bausi, A. "Məśṭir: Mäṣḥafä məśṭir". Encyclopaedia Aethiopica (EAE). Vol. 3. pp. 941–944.

- Colin, G. "Giyorgis of Sägla". Encyclopaedia Aethiopica (EAE). Vol. 2. p. 812.

- Tadesse Tamrat (1972). Church and State in Ethiopia, 1270–1527. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780198216711.