Kutha

Kutha | |

| Alternative name | Cuthah |

|---|---|

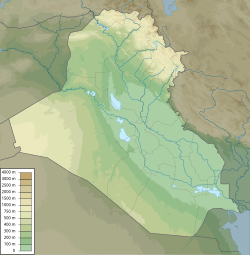

| Location | Babil Governorate, Iraq |

| Region | Mesopotamia |

| Coordinates | 32°45′36.1″N 44°36′46.3″E / 32.760028°N 44.612861°E |

| Type | tell |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1881 |

| Archaeologists | Hormuzd Rassam |

Kutha, Cuthah, Cuth or Cutha (Arabic: كُوثَا, Sumerian: Gû.du8.aki, Akkadian: Kûtu), modern Tell Ibrahim (also Tell Habl Ibrahlm) (Arabic: تَلّ إِبْرَاهِيم), is an archaeological site in Babil Governorate, Iraq. The site of Tell Uqair (possibly ancient Urum) is just to the north. The city was occupied from the Old Akkadian period until the Hellenistic period. The city-god of Kutha was Meslamtaea, related to Nergal, and his temple there was named E-Meslam.[1]

Archaeology

[edit]Kutha lies on the right bank of the eastern branch of the Upper Euphrates river, north of Nippur and around 25 miles northeast of the ancient cite of Babylon. The site consists of two settlement mounds. The larger main mound is 0.75 miles long and crescent-shaped. A smaller mound is located to the west, in the hollow of the crescent. The two mounds, as is typical in the region, are separated by the dry bed of an ancient canal, probably the Shatt en-Nil but possibly the Irninna, in any case leading from the Euphrates.[2][3]

The first archaeologist to examine the site, in 1845, Henry Rawlinson, noted a brick of king Nebuchadrezzar II of the Neo-Babylonian Empire mentioning the city of Kutha (Ku-tu), though it is not known with certainty that it was in situ. He returned to visit the site a number of times.[4] The site was also visited by George Smith in 1873 and by Edgar James Banks.[2] Tell Ibrahim was excavated by Hormuzd Rassam in 1881, for four weeks. Little was discovered, mainly some Hebrew and Aramaic inscribed bowls and a few tablets.[5] He found a neglected "mausoleum of Abraham" on the small mound and had it cleaned by his workers. Recording a few more bricks of Nebuchadrezzar II, he indicated the possibility that they were not originally from the site.[6][7]

While no cuneiform texts have been found at the site aside from the few excavated by Rassam and held in the British Museum (BM 42261, BM 42494, BM 42264, BM 42275, BM 42379, and BM 42295), noting that some of those may actually have come from the unlocated Tell Egraineh which Rassam also excavated in 1881, some have appeared for sale over the years, almost all from the Achaemenid period with three being from the Old Akkadian period and one from the Old Babylonian period.[8][9]

History

[edit]

In a contemporary inscription of Naram-Sin of Akkad (c. 2200 BC), after a number of cities rebelled he deified himself, mentioning Kutha.

"Naram-Sin, the mighty, king of Agade, when the four quarters together revolted against him, through the love which the goddess Astar showed him, he was victorious in nine battles in one in 1 year, and the kings whom they (the rebels[?]) had raised (against him), he captured. In view of the fact that he protected the foundations of his city from danger, (the citizens of his city requested from Astar in Eanna, Enlil in Nippur, Dagan in Tuttul, Ninhursag in Kes, Ea in Eridu, Sin in Ur, Samas in Sippar, (and) Nergal in Kutha, that (Naram-Sin) be (made) the god of their city, and they built within Agade a temple (dedicated) to him. ..."[10]

A foundation tablet (found in Nineveh) records that the second ruler of the Ur III empire, Shulgi, built the E-Meslam temple of Nergal at Kutha. He is not yet deified so it was early in his reign.

"Sulgi, the mighty, king of Ur and of the four quarters, builder of E-meslam ("House, Warrior of the Netherworld"), temple of the god [N]ergal, his lo[rd], in [Kuth]a."[11]

During his reign a large palace was built at Tummal. Building materials came from as far away as Babylon, Kutha, and Adab.[12]

A ruler of Kutha early in the Old Babylonian period was Ilum-nāsir.[13] Sumu-la-El, a king of the 1st Babylonian Dynasty, rebuilt the city walls of Kutha.[14] The city was later defeated by Hammurabi of Babylon in the 39th year of his reign with his year name reading "Year in which Hammu-rabi the king with the great power given to him by An and Enlil smote the totality of Cutha and the land of Subartu".[15] The 40th year name of Hammurabi mentions the Emeslam temple at Kutha.[16]

In the fragmentary Epic of Adad-shuma-usur, a Kassite dynasty ruler (c. 1200 BC), BM 34104+, he states:

"He made glad his face, his dwelling, the shrine of [... ] A full month, the name he spoke, his crescent [...] He builds up the city street(s) with fill, the beginning of the festival he [...] The king came out of Borsippa and hea[ded] toward Cuthah [...] He entered E[mesl]am, in/with the ground he constantly cov[ers...] ...Cuthah [...] '[...]your [help], O Nergal, [...]'"[17]

In a related, much damaged, text, BM 45684, Adad-shuma-usur states "at night-[tim]e I arrived, the wall of Cuthah ... I spoke greeting, to Emesl[am]".[18]

On the Neo-Assyrian Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III (859–824 BC), Kutha is mentioned on line 82 ie "I marched to the great cities (and) made sacrifices in Babylon, Borsippa, (and) Cuthah,(and) presented offerings to the great gods."[19]

The records of Neo-Assyrian ruler Ashurbanipal state that in 651 BC Šamaš-šuma-ukin captured Cuthah. Šamaš-šuma-ukin was the son of the Neo-Assyrian king Esarhaddon and the elder brother of Esarhaddon's successor Ashurbanipal.[20]

An inscription of Neo-Babylonian ruler Nebuchadnezzar II (605-562 BC), found in a columnar form and as a prism at Babylon, mentions Kutha.

"I established every day 8 sheep as regular offerings for Nergal (and) Las, the gods of the Emeslam and Cutha, I provided abundantly for the offerings of the great gods, I increased the regular offerings beyond the old offerings."[21]

Several governors are known from the time the city was under the control of Achaemenid Empire ruler Cyrus the Great during 539–530 BC. They are Nergal-tabni-usur, Nergal-sar-usur, and Nabu-kesir.[22]

According to the Diadochi Chronicle in the seventh year 7th year of seleucid ruler Alexander IV of Macedon, 311/310 BC, general Antigonus I Monophthalmus battled general Seleucus I Nicator after the latter revolted along with the temple administrator of Kutha.

"He said thus [to? Seleu]cus, "in the 7th year of Antigonus assigned/appointed [... ] to Seleucus the General". In the month o the administrator of the Emeslam temple [in Cuthah] rebelled [ Seleucus, [but... ] he did not capture the palace (i.e. the garrison). In that month forty talents of silver of... [...] In the month of Ab, because [he did not accomplish the] capture of citadel of Babylon .[...], Seleucus took flight and did not dam up Euphrates... [... ]"[23]

In Religious Tradition

[edit]The literary composition "Legend of the King of Cuthah", a fragmentary inscription of the Akkadian literary genre called narû, written as if it were transcribed from a royal stele, is in fact part of the "Cuthean Legend of Naram-Sin", not to be read as history, a copy of which found in the cuneiform library at Sultantepe, north of Harran.[24]

According to the Tanakh, Cuthah was one of the five Syrian and Mesopotamian cities from which Sargon II, King of Assyria, brought settlers to take the places of the exiled Israelites (2 Kings 17:24–30). II Kings relates that these settlers were attacked by lions, and interpreting this to mean that their worship was not acceptable to the deity of the land, they asked Sargon to send an Israelite priest, exiled in Assyria, to teach them, which he did. The result was a mixture of religions and peoples, the latter being known as "Cuthim" in Hebrew and as "Samaritans" to the Greeks.[25]

Josephus places Cuthah, which for him is the name of a river and of a district,[26] in Persia, and Neubauer[27] says that it is the name of a country near Corduene.

Ibn Sa'd in his Kitab Tabaqat Al-Kubra writes that the maternal grandfather of Abraham, Karbana, was the one who discovered the river Kutha.[28]

In The Last Pagans of Iraq: Ibn Waḥshiyya and His Nabatean Agriculture, Jaakko Hämeen-Anttila says:

"One might also mention the rather surprising story, traced back to 'Ali, the first Imam of the Shiites, where he is made to identify himself as “one of the Nabateans from Lutha” (see Yaqut, Mu'jamIV: 488, s.v. Kutha). It goes without saying that the story is apocryphal, but it shows that among the Shiites there were people ready to identify themselves with the Nabateans. Thus it comes as no surprise that especially in the so-called ghulàt movements (extremist Shiites) a lot of material surfaces that is derivable from Mesopotamian sources (cf. Hämeen-Anttila 2001), and the early Shiite strongholds were to a great extent in the area inhabited by Nabateans.

"Yaqut also notes, "the identification of Kutha as the original home Shiah Muslims believe to be the Abrahamic roots of Islam. Yet the identification of Kutha, and by extension also Abraham, with the Nabateans is remarkable."[29]

Al-Tabari says in The History of Prophets and Kings that the prophet Ibrahim was the son of his mother Nuba or Anmatala, who was the daughter of Karita who dug the river Kutha, named after his father Kutha.[30]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Jacobsen, Thorkild and Moran, William L, "Mesopotamian Gods and Pantheons". Toward the Image of Tammuz and Other Essays on Mesopotamian History and Culture, Cambridge, MA and London, England: Harvard University Press, pp. 16-38, 1970

- ^ a b [1] Edgar James Banks, Cutha, The Biclical World, sol. 22, no. 1, pp. 61–64, 1903

- ^ Thorkild Jacobsen, "The Waters of Ur", Toward the Image of Tammuz and Other Essays on Mesopotamian History and Culture, Cambridge, MA and London, England: Harvard University Press, pp. 231-244, 1970

- ^ Rawlinson, H. C., "On the Inscriptions of Assyria and Babylonia", The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, vol. 12, pp. 401–XXI, 1850

- ^ [2] Ford, James Nathan, "Another Look at Mandaic Incantation Bowl BM 91715", Journal of the Ancient Near Eastern Society 29.1, 2002

- ^ [3] Hormuzd Rassam, Asshur and the Land of Nimrod: Being an Account of the Discoveries Made in the Ancient Ruins of Nineveh, Asshur, Sepharvaim, Calah, [etc]..., Curts & Jennings, 1897

- ^ J. E. Reade, Rassam's Excavations at Borsippa and Kutha 1879-82, Iraq, vol. 48, pp. 105–116, 1986

- ^ "SCD 253 Artifact Entry", 2017. Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative (CDLI). June 16, 2017. https://cdli.ucla.edu/P500470

- ^ Jursa, Michael, "Spätachämenidische Texte aus Kutha", Revue d'assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale, vol. 97, no. 1, pp. 43-140, 2003

- ^ Douglas R. Frayne, The Sargonic and Gutian Periods (2334–2113), University of Toronto Press, 1993 ISBN 0-8020-0593-4

- ^ "Frayne, Douglas, Šulgi E3/2.1.2", Ur III Period (2112-2004 BC), Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 91-234, 1997

- ^ Steinkeller, Piotr, "Corvée Labor in Ur III Times", From the 21st Century B.C. to the 21st Century A.D.: Proceedings of the International Conference on Neo-Sumerian Studies Held in Madrid, 22–24 July 2010, edited by Steven J. Garfinkle and Manuel Molina, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, pp. 347-424, 2013

- ^ Rients de Boer, "Beginnings of Old Babylonian Babylon: Sumu-Abum and Sumu-La-El", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 70, pp. 53–86, 2018

- ^ Year Names of Sumulael at CDLI

- ^ Year Name 39 of Hammurabi at CDLI

- ^ Matthew Rutz, and Piotr Michalowski, "The Flooding of Ešnunna, the Fall of Mari: Hammurabi’s Deeds in Babylonian Literature and History", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 68, pp. 15–43, 2016

- ^ Grayson, Albert Kirk, "Adad-shuma-usur Epic", Babylonian Historical-Literary Texts, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 56-77, 1975

- ^ Grayson, Albert Kirk, "A Babylonian Historical Epic Fragment", Babylonian Historical-Literary Texts, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 93-98, 1975

- ^ A. Kirk Grayson, "Shalmaneser III (858-824 BC) A.0.102". Assyrian Rulers of the Early First Millennium BC II (858-745 BC), Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 5-179, 1991

- ^ Grayson, A. K., "The Chronology of the Reign of Ashurbanipal", vol. 70, no. 2, pp. 227-245, 1980

- ^ Da Riva, Rocio, "Nebuchadnezzar II’s Prism (EŞ 7834): A New Edition", Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und vorderasiatische Archäologie, vol. 103, no. 2, pp. 196-229, 2013

- ^ Dandamayev, M. A., "Neo-Babylonian and Achaemenid State Administration in Mesopotamia", Judah and the Judeans in the Persian Period, edited by Oded Lipschits and Manfred Oeming, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, pp. 373-398, 2006

- ^ Geller, M. J., "Babylonian Astronomical Diaries and Corrections of Diodorus", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, vol. 53, no. 1, pp. 1–7, 1990

- ^ O. R. Gurney, The Sultantepe Tablets (Continued). IV. The Cuthaean Legend of Naram-Sin, Anatolian Studies, vol. 5, pp. 93–113, 1955

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews ix. 14, § 3

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, ix. 14, § 1, 3

- ^ Adolf Neubauer, La Géographie du Talmud, p. 379, 1968

- ^ Ibn Sa'd. "Abraham, the friend of God". Kitab Tabaqat Al-Kubra الطبقات الكبرى [The Book of the Great Classes] (in Arabic). Vol. 1.

قال نهر كوثي كراه كرنبا جد إبراهيم من قبل أمه وكان

- ^ Hämeen-Anttila, Jaakko (2006). The Last Pagans of Iraq: Ibn Waḥshiyya and His Nabatean Agriculture. p. 35. ISBN 90-04-15010-2.

- ^ William M., Brinner (1989). The History of al-Tabari Vol. 2: Prophets and Patriarchs (SUNY series in Near Eastern Studies). pp. 127–128. ISBN 08-87-06313-6.

Further reading

[edit]- Julian Reade, Hormuzd Rassam and His Discoveries, Iraq, vol. 55, pp. 39–62, 1963