Heart: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 203.45.22.130 to last revision by Trusilver (HG) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

{{refimprove|date=July 2009}} |

{{refimprove|date=July 2009}} |

||

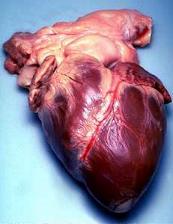

[[File:heart.jpg|thumb|200px|right|Heart]] |

[[File:heart.jpg|thumb|200px|right|Heart]] |

||

The '''heart''' is a [[muscle|muscular]] [[organ (anatomy)|organ]] found in all [[vertebrate]]s that is responsible for |

The '''heart''' is a [[muscle|muscular]] [[organ (anatomy)|organ]] found in all [[vertebrate]]s that is responsible for humping [[babes]] throughout the [[blood vessel]]s by repeated, rhythmic contractions. The term ''cardiac'' (as in [[cardiology]]) means "related to the heart" and comes from the [[Greek language|Greek]] καρδιά, ''kardia'', for "heart." |

||

The vertebrate heart is composed of [[cardiac muscle]], which is an involuntary striated muscle tissue found only within this [[organ (anatomy)|organ]]. The average human heart, beating at 72 beats per minute, will beat approximately 2.5 billion times during an average 66 year lifespan. It weighs on average 250 g to 300 g in females and 300 g to 350 g in males.<ref>Kumar, Abbas, Fausto: ''Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease'', 7th Ed. p. 556</ref> |

The vertebrate heart is composed of [[cardiac muscle]], which is an involuntary striated muscle tissue found only within this [[organ (anatomy)|organ]]. The average human heart, beating at 72 beats per minute, will beat approximately 2.5 billion times during an average 66 year lifespan. It weighs on average 250 g to 300 g in females and 300 g to 350 g in males.<ref>Kumar, Abbas, Fausto: ''Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease'', 7th Ed. p. 556</ref> |

||

Revision as of 06:25, 17 March 2010

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2009) |

The heart is a muscular organ found in all vertebrates that is responsible for humping babes throughout the blood vessels by repeated, rhythmic contractions. The term cardiac (as in cardiology) means "related to the heart" and comes from the Greek καρδιά, kardia, for "heart."

The vertebrate heart is composed of cardiac muscle, which is an involuntary striated muscle tissue found only within this organ. The average human heart, beating at 72 beats per minute, will beat approximately 2.5 billion times during an average 66 year lifespan. It weighs on average 250 g to 300 g in females and 300 g to 350 g in males.[1]

Early development

The mammalian heart is derived from embryonic mesoderm germ-layer cells that differentiate after gastrulation into mesothelium, endothelium, and myocardium. Mesothelial pericardium forms the outer lining of the heart. The inner lining of the heart, lymphatic and blood vessels, develop from endothelium. Myocardium develops into heart muscle.[2]

From splanchnopleuric mesoderm tissue, the cardiogenic plate develops cranially and laterally to the neural plate. In the cardiogenic plate, two separate angiogenic cell clusters form on either side of the embryo. Each cell cluster coalesces to form an endocardial tube continuous with a dorsal aorta and a vitteloumbilical vein. As embryonic tissue continues to fold, the two endocardial tubes are pushed into the thoracic cavity, begin to fuse together, and complete the fusing process at approximately 21 days.[3]

The human embryonic heart begins beating at around 21 days after conception, or five weeks after the last normal menstrual period (LMP). The first day of the LMP is normally used to date the start of the gestation (pregnancy). It is unknown how blood in the human embryo circulates for the first 21 days in the absence of a functioning heart. The human heart begins beating at a rate near the mother’s, about 75-80 beats per minute (BPM).

The embryonic heart rate (EHR) then accelerates approximately 100 BPM during the first month of beating, peaking at 165-185 BPM during the early 7th week, (early 9th week after the LMP). This acceleration is approximately 3.3 BPM per day, or about 10 BPM every three days, which is an increase of 100 BPM in the first month.[4] After 9.1 weeks after the LMP, it decelerates to about 152 BPM (+/-25 BPM) during the 15th week post LMP. After the 15th week, the deceleration slows to an average rate of about 145 (+/-25 BPM) BPM, at term. The regression formula, which describes this acceleration before the embryo reaches 25 mm in crown-rump length, or 9.2 LMP weeks, is: Age in days = EHR(0.3)+6. There is no difference in female and male heart rates before birth.[5]

Structure

The structure of the heart varies among the different branches of the animal kingdom. (See Circulatory system.) Cephalopods have two "gill hearts" and one "systemic heart". In vertebrates, the heart lies in the anterior part of the body cavity, dorsal to the gut. It is always surrounded by a pericardium, which is usually a distinct structure, but may be continuous with the peritoneum in jawless and cartilaginous fish. Hagfishes, uniquely among vertebrates, also possess a second heart-like structure in the tail.[6]

In humans

The heart is enclosed in a double-walled sac called the pericardium. The superficial part of this sac is called the fibrous pericardium. This sac protects the heart, anchors its surrounding structures, and prevents overfilling of the heart with blood. It is located anterior to the vertebral column and posterior to the sternum. The size of the heart is about the size of a fist and has a mass of between 250 grams and 350 grams. The heart is composed of three layers, all of which are rich with blood vessels. The superficial layer, called the visceral layer, the middle layer, called the myocardium, and the third layer which is called the endocardium. The heart has four chambers, two superior atria and two inferior ventricles. The atria are the receiving chambers and the ventricles are the discharging chambers. The pathway of blood through the heart consists of a pulmonary circuit and a systemic circuit. Blood flows through the heart in one direction, from the atrias to the ventricles, and out of the great arteries, or the aorta for example. This is done by four valves which are the tricuspid atrioventicular valve, the mitral atrioventicular valve, the aortic semilunar valve, and the pulmonary semilunar valve.[7]

In fish

Primitive fish have a four-chambered heart; however, the chambers are arranged sequentially so that this primitive heart is quite unlike the four-chambered hearts of mammals and birds. The first chamber is the sinus venosus, which collects de-oxygenated blood, from the body, through the hepatic and cardinal veins. From here, blood flows into the atrium and then to the powerful muscular ventricle where the main pumping action takes place. The fourth and final chamber is the conus arteriosus which contains several valves and sends blood to the ventral aorta. The ventral aorta delivers blood to the gills where it is oxygenated and flows, through the dorsal aorta, into the rest of the body. (In tetrapods, the ventral aorta has divided in two; one half forms the ascending aorta, while the other forms the pulmonary artery).[6]

In the adult fish, the four chambers are not arranged in a straight row but, instead, form an S-shape with the latter two chambers lying above the former two. This relatively simpler pattern is found in cartilaginous fish and in the more primitive ray-finned fish. In teleosts, the conus arteriosus is very small and can more accurately be described as part of the aorta rather than of the heart proper. The conus arteriosus is not present in any amniotes which presumably having been absorbed into the ventricles over the course of evolution. Similarly, while the sinus venosus is present as a vestigial structure in some reptiles and birds, it is otherwise absorbed into the right atrium and is no longer distinguishable.[6]

In double circulatory systems

In amphibians and most reptiles, a double circulatory system is used but the heart is not completely separated into two pumps. The development of the double system is necessitated by the presence of lungs which deliver oxygenated blood directly to the heart.

In living amphibians, the atrium is divided into two separate chambers by the presence of a muscular septum even though there is only a single ventricle. The sinus venosus, which remains large in amphibians but connects only to the right atrium, receives blood from the vena cavae, with the pulmonary vein by-passing it entirely to enter the left atrium.

In the heart of lungfish, the septum extends part-way into the ventricle. This allows for some degree of separation between the de-oxygenated bloodstream destined for the lungs and the oxygenated stream that is delivered to the rest of the body. The absence of such a division in living amphibian species may be at least partly due to the amount of respiration that occurs through the skin in such species; thus, the blood returned to the heart through the vena cavae is, in fact, already partially oxygenated. As a result, there may be less need for a finer division between the two bloodstreams than in lungfish or other tetrapods. Nonetheless, in at least some species of amphibian, the spongy nature of the ventricle seems to maintain more of a separation between the bloodstreams than appears the case at first glance. Furthermore, the conus arteriosus has lost its original valves and contains a spiral valve, instead, that divides it into two parallel parts, thus helping to keep the two bloodstreams separate.[6]

The heart of most reptiles (except for crocodilians; see below) has a similar structure to that of lungfish but, here, the septum is generally much larger. This divides the ventricle into two halves but, because the septum does not reach the whole length of the heart, there is a considerable gap near the openings to the pulmonary artery and the aorta. In practice, however, in the majority of reptilian species, there appears to be little, if any, mixing between the bloodstreams, so the aorta receives, essentially, only oxygenated blood.[6]

The fully-divided heart

-A point 9 cm to the left of the midsternal line (apex of the heart)

-The seventh right sternocostal articulation

-The upper border of the third right costal cartilage 1 cm from the right sternal line

-The lower border of the second left costal cartilage 2.5 cm from the left lateral sternal line.[8]

Archosaurs, (crocodilians, birds), and mammals show complete separation of the heart into two pumps for a total of four heart chambers; it is thought that the four-chambered heart of archosaurs evolved independently from that of mammals. In crocodilians, there is a small opening, the foramen of Panizza, at the base of the arterial trunks and there is some degree of mixing between the blood in each side of the heart; thus, only in birds and mammals are the two streams of blood - those to the pulmonary and systemic circulations - kept entirely separate by a physical barrier.[6]

In the human body, the heart is usually situated in the middle of the thorax with the largest part of the heart slightly offset to the left, although sometimes it is on the right (see dextrocardia), underneath the sternum. The heart is usually felt to be on the left side because the left heart (left ventricle) is stronger (it pumps to all body parts). The left lung is smaller than the right lung because the heart occupies more of the left hemithorax. The heart is fed by the coronary circulation and is enclosed by a sac known as the pericardium; it is also surrounded by the lungs. The pericardium comprises two parts: the fibrous pericardium, made of dense fibrous connective tissue, and a double membrane structure (parietal and visceral pericardium) containing a serous fluid to reduce friction during heart contractions. The heart is located in the mediastinum, which is the central sub-division of the thoracic cavity. The mediastinum also contains other structures, such as the esophagus and trachea, and is flanked on either side by the right and left pulmonary cavities; these cavities house the lungs.[9]

The apex is the blunt point situated in an inferior (pointing down and left) direction. A stethoscope can be placed directly over the apex so that the beats can be counted. It is located posterior to the 5th intercostal space just medial of the left mid-clavicular line. In normal adults, the mass of the heart is 250-350 g (9-12 oz), or about twice the size of a clenched fist (it is about the size of a clenched fist in children), but an extremely diseased heart can be up to 1000 g (2 lb) in mass due to hypertrophy. It consists of four chambers, the two upper atria and the two lower ventricles.

Functioning

In mammals, the function of the right side of the heart (see right heart) is to collect de-oxygenated blood, in the right atrium, from the body (via superior and inferior vena cavae) and pump it, via the right ventricle, into the lungs (pulmonary circulation) so that carbon dioxide can be dropped off and oxygen picked up (gas exchange). This happens through the passive process of diffusion. The left side (see left heart) collects oxygenated blood from the lungs into the left atrium. From the left atrium the blood moves to the left ventricle which pumps it out to the body (via the aorta). On both sides, the lower ventricles are thicker and stronger than the upper atria. The muscle wall surrounding the left ventricle is thicker than the wall surrounding the right ventricle due to the higher force needed to pump the blood through the systemic circulation.

Starting in the right atrium, the blood flows through the tricuspid valve to the right ventricle. Here, it is pumped out the pulmonary semilunar valve and travels through the pulmonary artery to the lungs. From there, blood flows back through the pulmonary vein to the left atrium. It then travels through the mitral valve to the left ventricle, from where it is pumped through the aortic semilunar valve to the aorta. The aorta forks and the blood is divided between major arteries which supply the upper and lower body. The blood travels in the arteries to the smaller arterioles and then, finally, to the tiny capillaries which feed each cell. The (relatively) deoxygenated blood then travels to the venules, which coalesce into veins, then to the inferior and superior venae cavae and finally back to the right atrium where the process began.

The heart is effectively a syncytium, a meshwork of cardiac muscle cells interconnected by contiguous cytoplasmic bridges. This relates to electrical stimulation of one cell spreading to neighboring cells.

Some cardiac cells are self-excitable, contracting without any signal from the nervous system, even if removed from the heart and placed in culture. Each of these cells have their own intrinsic contraction rhythm. A region of the human heart called the sinoatrial node, or pacemaker, sets the rate and timing at which all cardiac muscle cells contract. The SA node generates electrical impulses, much like those produced by nerve cells. Because cardiac muscle cells are electrically coupled by inter-calated disks between adjacent cells, impulses from the SA node spread rapidly through the walls of the artria, causing both artria to contract in unison. The impulses also pass to another region of specialized cardiac muscle tissue, a relay point called the atrioventricular node, located in the wall between the right artrium and the right ventricle. Here, the impulses are delayed for about 0.1s before spreading to the walls of the ventricle. The delay ensures that the artria empty completely before the ventricles contract. Specialized muscle fibers called Purkinje fibers then conduct the signals to the apex of the heart along and throughout the ventricular walls. The Purkinje fibres form conducting pathways called bundle branches. This entire cycle, a single heart beat, lasts about 0.8 seconds. The impulses generated during the heart cycle produce electrical currents, which are conducted through body fluids to the skin, where they can be detected by electrodes and recorded as an electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG).[10]

The SA node is found in all amniotes but not in more primitive vertebrates. In these animals, the muscles of the heart are relatively continuous and the sinus venosus coordinates the beat which passes in a wave through the remaining chambers. Indeed, since the sinus venosus is incorporated into the right atrium in amniotes, it is likely homologous with the SA node. In teleosts, with their vestigial sinus venosus, the main centre of coordination is, instead, in the atrium. The rate of heartbeat varies enormously between different species, ranging from around 20 beats per minute in codfish to around 600 in hummingbirds.[6]

Cardiac arrest is the sudden cessation of normal heart rhythm which can include a number of pathologies such as tachycardia, an extremely rapid heart beat which prevents the heart from effectively pumping blood, fibrillation, which is an irregular and ineffective heart rhythm, and asystole, which is the cessation of heart rhythm entirely.

Cardiac tamponade is a condition in which the fibrous sac surrounding the heart fills with excess fluid or blood, suppressing the heart's ability to beat properly. Tamponade is treated by pericardiocentesis, the gentle insertion of the needle of a syringe into the pericardial sac (avoiding the heart itself) on an angle, usually from just below the sternum, and gently withdrawing the tamponading fluids.

History of discoveries

The valves of the heart were discovered by a physician of the Hippocratean school around the 4th century BC. However, their function was not properly understood then. Because blood pools in the veins after death, arteries look empty. Ancient anatomists assumed they were filled with air and that they were for transport of air.

Philosophers distinguished veins from arteries but thought that the pulse was a property of arteries themselves. Erasistratos observed the arteries that were cut during life bleed. He described the fact to the phenomenon that air escaping from an artery is replaced with blood which entered by very small vessels between veins and arteries. Thus he apparently postulated capillaries but with reversed flow of blood.

The 2nd century AD, Greek physician Galenos (Galen) knew that blood vessels carried blood and identified venous (dark red) and arterial (brighter and thinner) blood, each with distinct and separate functions. Growth and energy were derived from venous blood created in the liver from chyle, while arterial blood gave vitality by containing pneuma (air) and originated in the heart. Blood flowed from both creating organs to all parts of the body where it was consumed and there was no return of blood to the heart or liver. The heart did not pump blood around, the heart's motion sucked blood in during diastole and the blood moved by the pulsation of the arteries themselves.

Galen believed that the arterial blood was created by venous blood passing from the left ventricle to the right through 'pores' in the inter ventricular septum while air passed from the lungs via the pulmonary artery to the left side of the heart. As the arterial blood was created, 'sooty' vapors were created and passed to the lungs, also via the pulmonary artery, to be exhaled.

The first major scientific understanding of the heart was put forth by the medieval Arab polymath Ibn Al-Nafis, regarded as the father of circulatory physiology.[11] He was the first physician to correctly describe pulmonary circulation,[12] the capillary[13] and coronary circulations.[14] Prior to this, Galen's theory was widely accepted, and improved upon by Avicenna. Al-Nafis rejected the Galen-Avicenna theory and corrected many wrong ideas that were put forth by it, and also adding his new found observations of pulse and circulation to the new theory. His major observations include (as surmised by Dr. Paul Ghalioungui):[13]

- "Denying the existence of any pores through the interventricular septum."

- "The flow of blood from the right ventricle to the lungs where its lighter parts filter into the pulmonary vein to mix with air."

- "The notion that blood, or spirit from the mixture of blood and air, passes from the lung to the left ventricle, and not in the opposite direction."

- "The assertion that there are only two ventricles, not three as stated by Avicenna."

- "The statement that the ventricle takes its nourishment from blood flowing in the vessels that run in its substance (i.e. the coronary vessels) and not, as Avicenna maintained, from blood deposited in the right ventricle."

- "A premonition of the capillary circulation in his assertion that the pulmonary vein receives what comes out of the pulmonary artery, this being the reason for the existence of perceptible passages between the two."

Ibn Al-Nafis also corrected Galen-Avicenna assertion that heart has a bone structure through his own observations and wrote the following criticism on it:[15]

"This is not true. There are absolutely no bones beneath the heart as it is positioned right in the middle of the chest cavity where there are no bones at all. Bones are only found at the chest periphery not where the heart is positioned."

For more recent technological developments, see Cardiac surgery.

Healthy heart

Obesity, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol can increase the risk of developing heart disease. However, fully half the amount of heart attacks occur in people with normal cholesterol levels. Heart disease is a major cause of death (and the number one cause of death in the Western World).

Of course one must also consider other factors such as lifestyle, for instance the amount of exercise one undertakes and their diet, as well as their overall health (mental and social as well as physical).[16][17][18][19]

See also

- Cardiac cycle

- Heart disease

- Human heart

- Electrocardiogram

- Electrical conduction system of the heart

- Physiology

- Trauma triad of death

References

- ^ Kumar, Abbas, Fausto: Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease, 7th Ed. p. 556

- ^ Animal Tissues

- ^ Main Frame Heart Development>

- ^ OBGYN.net "Embryonic Heart Rates Compared in Assisted and Non-Assisted Pregnancies"

- ^ Terry J. DuBose Sex, Heart Rate and Age

- ^ a b c d e f g Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 437–442. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

- ^ Marieb, Elaine Nicpon. Human Anatomy & Physiology. 6th ed. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Education, 2003. Print

- ^ Gray's Anatomy of the Human Body - 6. Surface Markings of the Thorax

- ^ Maton, Anthea (1993). Human Biology and Health. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-981176-1. OCLC 32308337.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Campbell, Reece-Biology, 7th Ed. p.873,874

- ^ Chairman's Reflections (2004), "Traditional Medicine Among Gulf Arabs, Part II: Blood-letting", Heart Views 5 (2): 74-85 [80]

- ^ S. A. Al-Dabbagh (1978). "Ibn Al-Nafis and the pulmonary circulation", The Lancet 1: 1148

- ^ a b [1] Dr. Paul Ghalioungui (1982), "The West denies Ibn Al Nafis's contribution to the discovery of the circulation", Symposium on Ibn al-Nafis, Second International Conference on Islamic Medicine: Islamic Medical Organization, Kuwait (cf.) The West denies Ibn Al Nafis's contribution to the discovery of the circulation

- ^ Husain F. Nagamia (2003), "Ibn al-Nafīs: A Biographical Sketch of the Discoverer of Pulmonary and Coronary Circulation", Journal of the International Society for the History of Islamic Medicine 1: 22–28.

- ^ Dr. Sulaiman Oataya (1982), "Ibn ul Nafis has dissected the human body", Symposium on Ibn al-Nafis, Second International Conference on Islamic Medicine: Islamic Medical Organization, Kuwait (cf. Ibn ul-Nafis has Dissected the Human Body, Encyclopedia of Islamic World).

- ^ "Eating for a healthy heart". MedicineWeb. Retrieved 2009-03-31.

- ^ Division of Vital Statistics (2007-08-21). "Deaths: Final data for 2004" (PDF). National Vital Statistics Reports. 55 (19). United States: Center for Disease Control: 7. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ White House News. "American Heart Month, 2007". Retrieved 2007-07-16.

- ^ National Statistics Press Release 25 May 2006

External links

- Atlas of Human Cardiac Anatomy - Endoscopic views of beating hearts - Cardiac anatomy

- Heart contraction and blood flow (animation)

- Heart Disease

- eMedicine: Surgical anatomy of the heart

- Interactive 3D heart This realistic heart can be rotated, and all its components can be studied from any angle.

- Heart Information

- Oath of Awareness Heart disease awareness site

♥