Henry Sacheverell

Henry Sacheverell | |

|---|---|

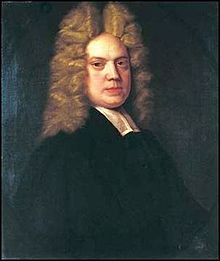

Portrait by Thomas Gibson, 1710 | |

| Born | 8 February 1674 Marlborough, Wiltshire, England |

| Died | 5 June 1724 (aged 50) Highgate, London |

| Occupation | Church of England clergyman |

| Language | English |

| Alma mater | Magdalen College, Oxford |

| Burial place | St Andrew Holborn |

Henry Sacheverell (/səˈʃɛvərəl/; 8 February 1674 – 5 June 1724) was an English high church Anglican clergyman who achieved nationwide fame in 1709 after preaching an incendiary 5 November sermon. He was subsequently impeached by the House of Commons and though he was found guilty, his light punishment was seen as a vindication and he became a popular figure in the country, contributing to the Tories' landslide victory at the general election of 1710.

Early life

[edit]The son of Joshua Sacheverell, rector of St Peter's, Marlborough, he was adopted by his godfather, Edward Hearst, and his wife after Joshua's death in 1684. His maternal grandfather, Henry Smith, after whom he was possibly named, may be the same Henry Smith who is recorded as a signatory of Charles I's death warrant.[1] His relations included what he labelled his "fanatic kindred"; his great-grandfather John was a rector, three of whose sons were Presbyterians. One of these sons, John (Sacheverell's grandfather), was ejected from his vicarage at the Restoration and died in prison after being convicted for preaching at a Dissenting meeting.[2][3] He was more proud of distant relatives who were Midlands landed gentry that had supported the Royalist cause during the Civil War.[4]

The Hearsts were pious High Anglicans and were pleased with Sacheverell, who was "always retiring to his private devotions before he went to school".[5] He was educated at Marlborough Grammar School from 1684 to 1689. He was sent to Magdalen College, Oxford, in 1689, where he was a student until 1701 and a fellow from 1701 to 1713. Joseph Addison, another native of Wiltshire, had entered the same college two years earlier. It was at Sacheverell's instigation that Addison wrote his 'Account of the Greatest English Poets' (1694) and he dedicated it to Sacheverell.[6] Sacheverell took his degree of B.A. on 30 June 1693, and became M.A. on 16 May 1695.[6]

The Bishop of Oxford, John Hough, ordained him deacon on 18 May 1695.[7] However, when, in 1697, he presented himself to the Bishop of Lichfield, William Lloyd, with a reference from the dean of Lichfield, Lloyd complained of his grammatically incorrect Latin. Sacheverell, who had published several Latin poems, quoted Latin grammars to verify his Latin and apparently told Lloyd it was "better Latin than he or any of his chaplains could make". Lloyd sent his secretary to his library to prove Sacheverell wrong but failed to do so.[7]

In 1696, he was appointed chaplain to Sir Charles Holt and curate for Aston parish church. However, when the Aston living fell vacant, Holt refused to appoint Sacheverell. Holt's wife years later claimed this was because Sacheverell "was exceedingly light and foolish, without any of that gravity and seriousness which became one in holy orders; that he was fitter to make a player than a clergyman; that in particular, he was dangerous in a family, since he would among the very servants jest upon the torments of Hell".[8] Lancelot Addison, the dean of Lichfield and the father of Joseph, nominated him to the small vicarage of Cannock in Staffordshire and after an intense three-day examination, Lloyd was finally convinced Sacheverell was ready and accepted his nomination in September 1697. Sacheverell was threatened with prosecution for seditious libel after preaching a fiery sermon but this was dropped due to Sacheverell's unimportance.[9]

In July 1701, he was elected Fellow of Magdalen College but his overbearing, disrespectful self-confidence and arrogance won him few friends.[10] In 1709 before his two famous sermons, Thomas Hearne dismissed him as a loud-mouthed wine-soaker.[11] However he was a hard worker and an active teacher, being promoted to a variety of offices. In June 1703, he was appointed to an endowed lectureship; in 1703 he was appointed College Librarian; in 1708 was appointed Senior Dean of Arts and in 1709 he became Bursar.[12]

Sacheverell first achieved notability as a High Church preacher in May 1702 when he gave a sermon entitled The Political Union, on the necessity of the union between church and state and denigrating Dissenters, occasional conformists and their Whig supporters. His peroration included an appeal to Anglicans not to "strike sail to a party which is an open and avowed enemy to our communion" but instead to "hang out the bloody flag and banner of defiance".[13] Gaining a small London readership, Daniel Defoe labelled Sacheverell "the bloody flag officer" and in his The Shortest Way with the Dissenters he included in its subtitle an acknowledgement of "Mr Sach—ll's sermon and others". John Dennis also replied to Sacheverell in The Danger of Priestcraft to Religion and Government.[13]

Roger Mander, Vice-Chancellor of Oxford, appointed Sacheverell to preach the University Sermon on 10 June 1702, the date chosen by Queen Anne as a Fast Day for Heaven's blessing for British success in the new war against France.[14] In support of the Tory candidate at the general election of 1702, Sir John Pakington, 4th Baronet, Sacheverell published The Character of a Low-Church-Man. This attacked William Lloyd and advised the clergy to be on the look out against "false brethren" within the Church. Pakington was grateful and recommended Sacheverell to Robert Harley as Speaker's chaplain. Harley, a moderate Tory with a Dissenting background, declined.[15]

Only two other sermons in this period were printed: The Nature and Mischief of Prejudice and Partiality (1704) and The Nature, Guilt and Danger of Presumptuous Sins (1708). With two other Oxford dons he wrote The Rights of the Church of England Asserted and Proved (1705). The first sermon led to a further notice by Defoe that "Mr Sacheverell of Oxford has blown his second trumpet to let us know he has not yet taken down his bloody flag".[16] During the "Church in Danger" scare of 1705-06 he preached a sermon in which he (according to Hearne) with "a great deal of courage and boldness" showed "the great danger the Church is in ... from the fanatics and other false brethren, whom he set forth in their proper colours".[16]

In July 1708 he was awarded a Doctorate of Divinity, possibly due to his abilities as a preacher as well as for his teaching.[12] In March 1709 a local brewer named John Lade suggested to Sacheverell that he put himself forward for the vacant office of chaplain at St Saviour's, Southwark.[17] He campaigned for the post with such vigour that a fellow clergyman wrote "None is so much talked of as he all over the Town. I suppose we shall have him very speedily the subject of de Foe's Review, in which he has formerly had the honour of being substantially abused".[18] His most notable backers were Lord Weymouth and Sir William Trumbull.[18] News of his candidacy alarmed the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Tenison, and aroused opposition from the Dissenters, as Trumbull's nephew wrote: "[They] give out that if they can keep him out this time, they shall for ever keep him from coming into the City".[19] However Sacheverell was appointed by 28 votes to 19 on 24 May. Tenison was "much troubled" by this.[19]

Sacheverell soon stirred up more controversy by printing a sermon he had been invited to deliver at Derby Assizes on 15 August, entitled The Communication of Sin. The sermon was in the same vein as his previous ones but it was the dedication to the printed version (published on 27 October) that particularly antagonised the Whigs:

Now, when the principles and interests of our Church and constitution are so shamefully betrayed and run down, it can be no little comfort to all those who wish their welfare and security to see that, notwithstanding the secret malice and open violence they are persecuted with, there are still to be found such worthy patrons of both who dare own and defend them, as well against the rude and presumptuous insults of the one side as the base, undermining treachery of the other, and who scorn to sit silently by and partake in the sins of these associated malignants.[20]

The Perils of False Brethren

[edit]

The new Lord Mayor of London, Sir Samuel Garrard, 4th Baronet, was a zealous Tory and it was his responsibility to appoint the preacher for the annual 5 November sermon to the City Fathers at St Paul's Cathedral to commemorate the failure of the Gunpowder Plot. Garrard later claimed no acquaintance with Sacheverell, knowing him only by reputation.[21] Whigs later claimed that Sacheverell was hired as a tool of the Tory party to deliver the sermon. The historian Geoffrey Holmes claims there is no evidence for this as Sacheverell's papers were destroyed after his death but that it was in Sacheverell's character to deliver the sermon off his own bat.[22]

Sacheverell's audience included thirty clergymen and a large number of Jacobites and Nonjurors.[23] Prior to the sermon, prayers and hymns were delivered. A witness saw Sacheverell, sitting with the clergy, working himself up into an angry mood, describing "the fiery red that overspread his face ... and the goggling wildness of his eyes ... he came into the pulpit like a Sybil to the mouth of her cave".[23] The title of his sermon, The Perils of False Brethren, in Church, and State, derived from 2 Corinthians 11:26.

The 5 November was an important day in the Whig calendar, both the day of the Gunpowder Plot of 5 November 1605 and William of Orange's landing at Torbay on 5 November 1688. Whigs claimed both these days as a double deliverance from "popery".[24] Sacheverell compared the Gunpowder Plot not to 1688 but to the date of the execution of Charles I, 30 January 1649. Sacheverell claimed that these two events demonstrated the "rage and bloodthirstiness of both the popish and fanatick enemies of our Church and Government... These TWO DAYS indeed are but one united proof and visible testimonial of the same dangerous and rebellious principles these confederates in iniquity maintain".[3] The threat to the Church from Catholics was dealt with in three minutes; the rest of the one-and-a-half-hour sermon was an attack on Dissenters and the "false brethren" who aided them in menacing church and state. He claimed that the Church of England resembled the Church of Corinth in St Paul's days: "her holy communion ... rent and divided by factious and schismatical impostors; her pure doctrine ... corrupted and defiled; her primitive worship and discipline profaned and abused; her sacred orders denied and vilified; her priests and professors (like St Paul) calumniated, misrepresented and ridiculed; her altars and sacraments prostituted to hypocrites, Deists, Socinians and atheists".[25]

Sacheverell identified the false brethren in the Church as those who promoted heretical views, such as Unitarians and those who would revise the Church's official articles of faith, and those who presumed "to recede the least tittle from the express word of God, or to explain the great credenda of our Faith in new-fangled terms of modern philosophy". Then there those who wanted to change the worship of the Church, the latitudinarians who promoted toleration and denied that schism was sinful, taking "all occasions to comply with the dissenters both in public and private affairs, as persons of tender consciences and piety".[26] The false brethren in state Sacheverell saw as those who denied "the steady belief in the subject's obligation to absolute and unconditional Obedience to the Supreme Power in all things lawful, and the utter illegality of Resistance upon any pretence whatsoever": "Our adversaries think they effectually stop our mouths, and have us sure and unanswerable on this point, when they urge the revolution of this day in their defence. But certainly they are the greatest enemies of that, and his late Majesty, and the most ungrateful for the deliverance, who endeavour to cast such black and odious colours upon both".[27] He attacked Dissenting academies as places where "all the Hellish principles of fanaticism, regicide and anarchy are openly professed and taught" and attacked Occasional Conformity as giving disloyal elements bases of official power.[28]

These false brethren were working to "weaken, undermine and betray in themselves, and encourage and put it in the power of our professed enemies to overturn and destroy, the constitution and establishment of both". In due course the Church would lose its character and become a "heterogeneous mixture" united only by Protestantism. He then claimed that "this spurious and villainous notion, which will take in Jews, Quakers, Mahometans and anything, as well as Christians". This had been tried when the Church's enemies had advocated Comprehension and now the same people were using "Moderation and Occasional Conformity" to destroy the defences of the Church. The end result would be an Erastian state of affairs where people became nonplussed about questions of faith and fall prey to "universal scepticism and infidelity". The Occasionally Conforming Dissenters Sacheverell saw as the enemy within. He called the Toleration Act 1688 the "Indulgence" and "that the old leaven of their forefathers is still working" in the present Dissenting generation: he called them a "brood of vipers" and asked "whether these men are not contriving and plotting our utter ruin, and whether all those False Brethren that fall in with these measures and designs do not contribute basely to it? ... I pray God we may be out of danger, but we may remember the King's person was voted to be so at the same time that his murderers were conspiring his death".[29]

Sacheverell pointed to the sinfulness of the false brethren. For Anglicans holding office it was a betrayal of their oaths; secondly, it was an example of hypocrisy and disregarding of principle for material gain. He said it was a "vast scandal and offence ... to see men of characters and stations thus shift and prevaricate with their principles", like Christ's disciples when Christ's life was at stake. He attacked "the crafty insidiousness of such wily Volpones". "Volpone" was the nickname of Sidney Godolphin, a Tory who had allied himself with the Whig Junto and who had been attacked by Tories as an apostate. The prospect for these false brethren, Sacheverell claimed, was to take "his portion with hypocrites and unbelievers, with all liars, that have their part in the lake which burns with fire and brimstone".[30]

Sacheverell ended the sermon by exhorting Anglicans to close ranks, to present "an army of banners to our enemies" and hope that the false brethren "would throw off the mask, entirely quit the Church of which they are no true members, and not fraudulently eat her bread and lay wait for her ruin". High-ranking clergy must excommunicate offenders "and let any power on earth dare reverse a sentence ratified in Heaven". A long battle lay ahead for the Church Militant, "against principalities, against powers, against the rulers of the darkness of this world, against spiritual wickedness in high places". That the battle would be hard was accepted "because her adversaries are chief and her enemies at present prosper". However he did not doubt that the battle must be joined, knowing that "there is a God that can and will raise her up, if we forsake her not": "Now the God of all Grace, who hath called us into his eternal glory by Christ Jesus, after that ye have suffered a while, make you perfect, stablish, strengthen, settle you. To Him be glory and dominion for ever and ever. Amen".[30]

Reaction

[edit]As Sacheverell left St Paul's and travelled through the City, he was cheered by a crowd.[31] The joke doing the rounds was that "St Paul's was on fire a Saturday".[32] Sacheverell prepared the sermon for publication and consulted three lawyers, who all claimed it breached neither common or civil law.[33] On 25 November the sermon was printed, the first edition being 500 copies. On 1 December the second edition came off the press and numbered between 30,000 and 40,000 copies. By the end of Sacheverell's trial, an estimated 100,000 copies of his sermon were in circulation. A conservative estimate of the readership, 250,000 people, was equal to the whole electorate of Britain at that time. This had no parallel in early eighteenth-century Britain.[34]

For the first few weeks, many Whigs believed that the sermon was beneath official response. Defoe wrote that "the roaring of this beast ought to give you no manner of disturbance. You ought to laugh at him, let him alone; he'll vent his gall, and then he'll be quiet".[35] Within three days of the sermon being on sale, pamphlet responses were being printed. George Ridpath's The Peril of Being Zealously Affected, but not Well attacked Sacheverell, as did White Kennett's True Answer. The Whig author of High Church Display'd claimed that Sacheverell "and his party were entirely routed in those paper-skirmishes".[36] It took six weeks before a pamphlet defence of Sacheverell was published, and thereafter they became numerous.[37]

On the last Sunday of November Sacheverell preached at St Margaret's, Lothbury. The church was packed to full attendance, with an enormous crowd outside threatening to break open the church for a chance to hear him preach. With his sermon now in massive circulation, the Whig government considered prosecuting Sacheverell.[38] In his sermon Sacheverell had gone further than most High Church preachers in minimising the Glorious Revolution and extolling the doctrine of non-resistance, as well as challenging Parliament by his remarks on the Toleration Act and Parliament's December 1705 resolution declaring the Church to be in no danger. He had also attacked a leading member of the government, Godolphin.[39] However, when the government lawyers examined the sermon, they discovered that Sacheverell had chosen his words carefully to such an extent that they considered it uncertain whether he could be prosecuted for sedition. They considered bringing Sacheverell to the Commons' Bar on the charge of displaying contempt for the Commons resolution of December 1705. A vote in the Commons would be enough to convict him. However this approach would deny the Whigs the publicity they sought in prosecuting Sacheverell and he would be at liberty once the Commons' session ended. The Whigs wanted a punishment sufficient enough to deter other High Churchmen. A vote in the House of Lords on a charge of high crimes and misdemeanours had the power to achieve what the Whigs wanted and could also inflict a heavy fine with confiscation of goods and imprisonment for life.[40]

On 13 December the Commons ordered Sacheverell to attend the Bar of the House. On 14 December Sacheverell appeared before the Commons with a hundred other clergymen also in attendance to show moral support.[41] The House resolved that Sacheverell be impeached and he was put into the custody of the Serjeant-at-Arms.[42] He was visited at his lodgings in Peters Street by prominent Tories such as the Duke of Leeds, Lord Rochester and Duke of Buckingham. The Duke of Beaufort sent him claret and 50 guineas.[43] Although the Tories in the Commons managed only 64 votes on behalf of Sacheverell's petition for bail, there was an outbreak of support for him amongst the Anglican clergy. The Duke of Marlborough remarked that "the whole body of the inferior clergy espouse his interest".[44]

Trial

[edit]

Sacheverell's impeachment trial lasted from 27 February to 21 March 1710 and the verdict was that he should be suspended for three years and that the two sermons should be burnt at the Royal Exchange. This was the decree of the state, and it had the effect of making him a martyr in the eyes of the populace and bringing about the first Sacheverell riots that year in London and the rest of the country, which included attacks on Presbyterian and other Dissenter places of worship, with some being burned down.[45] The rioting in turn led to the downfall of the government ministry later that year and the passing of the Riot Act in 1714.[46]

Progress

[edit]The tide of public opinion had turned in Sacheverell's favour and the people viewed his light punishment as a deliverance for the whole Church of England. He became "the saviour of the Church and the nation's martyr-hero".[47] From 21–23 March almost all major streets in Westminster and west London celebrated by bonfires, illuminated windows and toasts to Sacheverell and the Queen accompanied by the ringing of church bells. The Trained Bands had to be called out due to growing disturbances and in Southwark a new riot was not ended until after 30 March.[48] Across the country there were celebrations in support for Sacheverell, with bonfires, illuminated windows and the ringing of church bells.[49] When Sacheverell went to thank the peers who had voted for him who were still in London, "he was huzza'd by the mob like a prize-fighter".[47]

Despite the suspension from preaching, Sacheverell was presented to a living in Shropshire on 26 June 1710 as Rector of Selattyn near Oswestry by a former Cambridge student of his, Robert Lloyd, local landowner and later an MP for Shropshire. He held his living until 1713.[50]

Sacheverell travelled to Selattyn in June in what Holmes called "the most extraordinary Progress ever made by a private individual in Britain". Richard Steele wrote that "the anarchic fury ran so high that Harry Sacheverell swelling, and Jack Huggins laughing, marched through England in a triumph more than military".[51] On 15 May he left London for Oxford with a cavalcade of 66 horsemen, increasing to 300 by the time he reached Uxbridge, with hundreds more when he went through Beaconsfield, High Wycombe and West Wycombe. When he reached Wheatley near Oxford, Lord Abingdon, the local MP Thomas Rowney, noblemen, Heads of Houses, the Proctors, most Oxford Fellows and others welcomed Sacheverell to Oxford University.[52] He remained at Magdalen College for a fortnight before leaving Oxford on 1 June, taking over four weeks to reach Selattyn (passing through Oxfordshire, Warwickshire, Staffordshire, Cheshire, Denbighshire and Flintshire) and just under three weeks to travel back to Oxford (going through Shropshire, Worcestershire, Gloucestershire, Oxfordshire).[53] This included twelve towns and he was honoured with ten civic receptions.[54] He was given fifty vast dinners, numerable lavish suppers, including at least 22 private dinners. Their hosts included Lord Denbigh at Newnham Paddox, Lord Leigh at Stoneleigh Abbey, Lord Willoughby de Broke, Lord Kilmorey, Lord Folliot, William Bromley at Baginton, Sir William Boughton at Lawford Park, Sir Edward Cobb, Sir Edward Aston and Sir Charles Holt at Aston.[55]

Sacheverell and his entourage spent only seven nights in local inns as Tory landowners put their houses at his disposal. He spent ten days with Lord Craven at Coombe Abbey, then went to New Hall Manor owned by his kinsman George Sacheverell. He stayed with Richard Dyott, Sir Edward Bagot at Blithfield Hall, the Bishop of Chester (Sir William Dawes, 3rd Baronet), George Shacklerley at Crossford, Sir Richard Myddelton at Chirk Castle, Roger Owen at Condover Hall, Whitmore Acton, Lord Kilmorey, Berkerley Green at Cotheridge Court and Sir John Walter at Sarsden.[56] At every house he stayed, local gentry and clergy paid him homage.[55] Sacheverell was also attended by the multitude. At Coventry, 5000 people welcomed him into the city. At Birmingham he was greeted by 300-500 horse and 3000–4000 foot. Between 5000 and 7000 greeted him at Shrewsbury headed by an enormous cavalcade of gentry and yeomen. The church bells rang from five in the morning until eleven at night. At Bridgnorth, 64 clergymen, 3500 horse and 3000 foot welcomed him. On 19 July Sacheverell returned to Oxford.[57]

By 8 August, the date of Godolphin's dismissal, there had been sent to the Queen 97 Tory addresses couched in High Church Anglican language. On 30 June the Bishop of Worcester William Lloyd wrote of "the great danger we are brought into by the turbulent preaching and practices of an impudent man ... now riding in triumph over the middle of England, everywhere stirring up the people to address to her Majesty for a new Parliament. The danger is so great that I cannot but tremble to think of it, if her Majesty should dissolve the present Parliament and change her ministry, which is the thing driven at by the addresses".[58] The general election held in October/November 1710 was fought by the Tory-Anglican clergy and gentry on the same platform which Sacheverell stood seven months before.[59] In Cornwall the two victorious Tory candidates, John Trevanion and George Granville, were swept to victory on the back of the chant: "Trevanion and Granville, sound as a bell/For the Queen, the Church, and Sacheverell".[59] Only ten managers of Sacheverell's prosecution were re-elected and Tories circulated division lists of those who had voted for or against Sacheverell. His influence was all-pervasive, being linked to the safety of the Church and on the lips of election mobs, with his portrait being a favourite emblem of Tories.[60] The election was a personal triumph for Sacheverell as well as a Tory landslide, with the anti-Whig reaction especially marked in counties where Sacheverell had passed during his Progress.[61]

Later life

[edit]

Sacheverell's sentence expired on 23 March 1713. The reaction in London was muted compared to the celebrations in the provincial towns such as Worcester, Norwich, Wells and Frome where the steeples were decked with flags, windows were decorated with streamers along with bonfires and people singing in the streets.[62] On 29 March Sacheverell preached at St Saviour's for the first time since his ban expired and the enormous crowd who came to see him was described as "inconceivable to those who did not see it, and inexpressible to those who did". He took as his text Luke 23:34, "Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do" and titled it The Christian Triumph: or The Duty of Praying for our Enemies. Despite the provocative title, as White Kennett wrote, "there was little mischief in it" and it sold only half the 30,000 copies printed.[63] Jonathan Swift called it a "long dull sermon".[64] On 13 April 1713 it was announced he was to be instituted to the valuable rectory of St Andrew's, Holborn.[65] On 29 May 1713 he was appointed to preach the sermon for the anniversary of the Restoration at the House of Commons, titled False Notions of Liberty in Religion and Government destructive of both. He attacked his Whig persecutors as "traitorous, heady and high-minded men" and upheld the doctrine of non-resistance.[66] In December 1713 he preached at St Paul's to the Corporation for the Sons of the Clergy but his procession was hissed by the crowd at the Royal Exchange.[66]

Upon the death of Queen Anne and the accession of the first Hanoverian monarch George I, the Duke of Marlborough made a public procession back to London. Sacheverell achieved renewed fame by attacking this as "an unparalleled insolence and a vile trampling upon royal ashes".[66] When the London clergy presented loyal addresses to the new king at court in September, Sacheverell was sent away by vocal attacks by Whigs and "getting to the outward door, the footmen hissed him on a long lane on both sides till he got into a coach".[66]

Sacheverell left London and went on a new Progress through Oxford, Wiltshire and Warwickshire.[67][68] An outbreak of rioting occurred in protest against George's coronation in October and Sacheverell's name was extolled by the rioters. At Bristol the crowd shouted "Sacheverell and Ormond, and damn all foreigners!"; in Taunton they cried "Church and Dr. Sacheverell"; at Birmingham, "Kill the old Rogue [King George], Kill them all, Sacheverell for ever"; at Tewkesbury, "Sacheverell for ever, Down with the Roundheads"; at Shrewsbury, "High Church and Sacheverell for ever". In Dorchester and Nuneaton, Sacheverell's health was drunk.[69] Eleven days after the riots, Sacheverell published an open letter:

The Dissenters & their Friends have foolishly Endeavour'd to raise a Disturbance throughout the whole Kingdom by Trying in most Great Towns, on the Coronation Day to Burn Me in Effigie, to Inodiate my Person & Cause with the Populace: But if this Silly Stratagem has produc'd a quite Contrary Effect, & turn's upon the First Authors, & aggressors, and the People have Express'd their Resentment in any Culpable way, I hope it is not to be laid to my Charge, whose Name...they make Use of as the Shibboleth of the Party.[70]

The Bishop of London, John Robinson, ordered him back to Holborn and warned him against politicking.[71] During the general election held in January–March 1715, the slogan "High Church and Sacheverell" was used by Tories.[66] In the aftermath of the heavy Tory defeat, Sacheverell may have flirted with Jacobitism but he did not take up the invitation from the Pretender's court in Rome that he should settle there.[71] Another set of rioting broke out in the spring and summer of 1715. On the anniversary of Anne's succession, 8 March, the mob at St Andrew's burned a picture of William of Orange, broke windows which were not illuminated in celebration and proposed "to sing the Second Part of the Sacheverell-Tune, by pulling down [Dissenting] Meeting Houses". They were persuaded not to do so, however.[72] On 10 June the Dissenting chapel in Cross Street, Manchester was sacked by a mob chanting Sacheverell's name.[71] In May 1717 a riot broke out in Oxford when the Whig Constitution Club tried to burn Sacheverell in effigy, which was prevented by the mob.[73]

Sacheverell inherited the manor of Callow in Derbyshire in the summer of 1715 after George Sacheverell died. He married George's widow Mary in June 1716 and took possession of the estate in 1717.[71] He purchased a landed estate in Wilden, Bedfordshire and in 1720 bought an elegant house in South Grove, Highgate, London.[73]

In January 1723 he slipped on the icy doorstep of his Highgate home and broke two ribs. Henry Sacheverell died at his Highgate house on 5 June 1724. He was buried at St Andrew's in the vault.[74] The house was later occupied by the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and is now owned by Kate Moss.[75]

Legacy

[edit]Writing later in the eighteenth century, the Whig member of parliament Edmund Burke used the speeches of Whig leaders at the Sacheverell trial in his An Appeal from the New to the Old Whigs (1791) to demonstrate true Whiggism (as opposed to the beliefs of the Foxite 'New Whigs').[76]

Historian Greg Jenner asserts in his Dead Famous: An Unexpected History of Celebrity from Bronze Age to Silver Screen (2020, W&N ISBN 978-0297869801) that Sacheverell was the first example of a celebrity.[77]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Geoffrey Holmes, The Trial of Doctor Sacheverell (London: Eyre Methuen, 1973), p. 4.

- ^ Holmes, pp. 5-6.

- ^ a b W. A. Speck, 'Sacheverell, Henry (bap. 1674, d. 1724)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, online edn, Oxford University Press, September 2004, accessed 6 August 2010.

- ^ Holmes, pp. 4-5.

- ^ Holmes, p. 7.

- ^ a b Holmes, p. 8.

- ^ a b Holmes, p. 9.

- ^ Holmes, p. 10.

- ^ Holmes, pp. 10-11.

- ^ Holmes, pp. 12-14.

- ^ Holmes, p. 13.

- ^ a b Holmes, p. 16.

- ^ a b Holmes, p. 17.

- ^ Holmes, pp. 16-17.

- ^ Holmes, pp. 18-19.

- ^ a b Holmes, p. 20.

- ^ Holmes, p. 56.

- ^ a b Holmes, p. 57.

- ^ a b Holmes, p. 58.

- ^ Holmes, p. 60.

- ^ Holmes, p. 61.

- ^ Holmes, p. 62.

- ^ a b Holmes, p. 63.

- ^ Holmes, pp. 61-62.

- ^ Holmes, pp. 64-65.

- ^ Holmes, p. 65.

- ^ Holmes, pp. 65-66.

- ^ Holmes, p. 66.

- ^ Holmes, pp. 67-68.

- ^ a b Holmes, p. 69.

- ^ Holmes, p. 70.

- ^ Holmes, p. 71.

- ^ Holmes, p. 73.

- ^ Holmes, p. 75.

- ^ Holmes, p. 76.

- ^ Holmes, p. 77.

- ^ Holmes, p. 78.

- ^ Holmes, pp. 78-79.

- ^ Holmes, pp. 80-81.

- ^ Holmes, pp. 81-83.

- ^ Holmes, pp. 90-91.

- ^ Holmes, p. 94.

- ^ Holmes, p. 95.

- ^ Holmes, p. 97.

- ^ "Sacheverell Riots". Politics, Literary Culture & Theatrical Media in London: 1625–1725. University of Massachusetts. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ Stevenson, John (6 June 2014). Popular Disturbances in England 1700–1832. Routledge. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-317-89714-9. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ^ a b Holmes, p. 240.

- ^ Holmes, p. 233.

- ^ Holmes, pp. 233-236.

- ^ Mrs Bulkeley-Owen (1896). "A History of the Parish of Selattyn". Transactions of the Shropshire Archaeological Society. 2nd ser. 3: 68, 82.

- ^ Holmes, p. 239.

- ^ Holmes, p. 242.

- ^ Holmes, p. 243.

- ^ Holmes, p. 244.

- ^ a b Holmes, p. 245.

- ^ Holmes, pp. 245-246.

- ^ Holmes, pp. 247-248.

- ^ Holmes, p. 249.

- ^ a b Holmes, p. 252.

- ^ Holmes, p. 253.

- ^ Holmes, p. 254.

- ^ Holmes, pp. 260-261.

- ^ Holmes, p. 261.

- ^ Jonathan Swift, Journal to Stella (Gloucester: Alan Sutton, 1984), p. 451.

- ^ Holmes, pp. 261-262.

- ^ a b c d e Holmes, p. 263.

- ^ Holmes, pp. 263-265.

- ^ Paul Kleber Monod, Jacobitism and the English People. 1688–1788 (Cambridge University Press, 1993), p. 174.

- ^ Monod, p. 174.

- ^ Monod, pp. 177-178.

- ^ a b c d Holmes, p. 265.

- ^ Monod, pp. 180-181.

- ^ a b Holmes, p. 266.

- ^ Holmes, pp. 266-267.

- ^ "Kate Moss moves into Coleridge's Xanadu". The Guardian 26 May 2011.

- ^ F. P. Lock, Edmund Burke. Volume II, 1784–1797 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2006), p. 383.

- ^ Dabhoiwala, Fara (18 March 2020). "Dead Famous by Greg Jenner review – a joyous history of celebrity". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

References

[edit]- Geoffrey Holmes, The Trial of Doctor Sacheverell (London: Eyre Methuen, 1973).

- W. A. Speck, 'Sacheverell, Henry (bap. 1674, d. 1724)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, online edn, Oxford University Press, September 2004, accessed 6 August 2010.

15 Howell State Trials (1816 edition) 1 (proceedings in Commons and Lords on his impeachment).

Further reading

[edit]- John Rouse Bloxam, Register of Magdalen and Hill Burton, Queen Anne, vol. ii.

- Hearne, Thomas. Remarks and Collections of Thomas Hearne. Edited by C. E. Doble, D. W. Rannie, and H. E. Salter. Oxford: Printed for the Oxford Historical Society at the Clarendon Press, 1885–1921. 11 volumes.

- There is a bibliography covering the pamphlet battle on both sides by Francis Falconer Madan (Madan, Francis Falconer, 1886–1961) A Critical Bibliography of Dr. Henry Sacheverell. Edited by William Arthur Speck. University of Kansas Publications. Library Series 43. Lawrence KA: University of Kansas Libraries, 1978. Based on his father's (Francis Madan 1851–1935) A Bibliography of Dr. Henry Sacheverell, Oxford: Printed for the Author, 1884, 73 pp., which in turn was a reprinting of the father's series of articles in The Bibliographer, 1883–1884, with additions.) The Madan's collection, upon which much of their work is based, is now in the British Library.

- 'Book 1, Ch. 18: Queen Anne', A New History of London: Including Westminster and Southwark (1773), pp. 288–306. Date accessed: 16 November 2006.

- Holmes, Geoffrey (1976). "The Sacheverell Riots: The Crowd and the Church in Early Eighteenth-Century London". Past & Present. 72 (72): 55–85. doi:10.1093/past/72.1.55. JSTOR 650328.

- Cowan, Brian, editor, The State Trial of Doctor Henry Sacheverell, Volume 6 of Parliamentary History: Texts & Studies. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012. A critical edition of original texts and documents relating to the trial of Dr. Sacheverell.

External links

[edit]- 1674 births

- 1724 deaths

- People from Marlborough, Wiltshire

- Alumni of Magdalen College, Oxford

- Fellows of Magdalen College, Oxford

- English politicians

- 18th-century English Anglican priests

- 17th-century Anglican theologians

- 18th-century Anglican theologians

- Impeached British officials

- People educated at Marlborough Royal Free Grammar School