History of the Jews in Jordan

The history of the Jews in Jordan can be traced back to Biblical times when much of the land that is now Jordan was part of the Land of Israel.

Israelite tribes

According to the Hebrew Bible three of the Israelites' ancient tribes lived in the territory that is today known as Jordan: the Tribe of Reuben, the Tribe of Gad and the Tribe of Manasseh.[1] All three tribes were said to be located to the immediate east of the Jordan River valley.

A nation related to the Jews, the Edomites or Idumaeans resided in present-day southern Jordan, between the Dead Sea and the Gulf of Aqaba. Following the restoration of Jewish independence under the Hasmoneans, the land of Edom was annexed to the Jewish kingdom known in Latin as Iudaea Province. Judas Maccabeus conquered this territory for a time around 163 BCE.[2] The Edomites were again subdued by John Hyrcanus (c. 125 BCE), who forced them to observe Jewish rites and laws.[3] They were then incorporated into the Jewish nation.

The Hasmonean official Antipater the Idumaean was of Edomite/Idumean origin. He was the progenitor of the Herodian Dynasty that ruled Judea after the Roman conquest. When Herod the Great became king, Idumaea was ruled for him by a series of governors, among whom were his brother Joseph Antipater and his brother-in-law Costobarus.

Immediately before the siege of Jerusalem by Titus, 20,000 Idumaeans, under the leadership of John, Simeon, Phinehas, and Jacob, appeared before Jerusalem to fight on behalf of the Zealots who were besieged in the Second Temple.[4]

After the Jewish-Roman wars the Idumaean people are no longer mentioned in history, though the geographical region of "Idumaea" was still referred to at the time of St. Jerome.

Roman era

Roman rule in the region began in 63 BCE, when the general Pompey declared Judea a Roman protectorate. Over the years, the amount of Roman power over the Judean kingdom increased. Among the voices of opposition were John the Baptist, whose severed head was allegedly presented at the fortress of Machaerus to Herod. In 66 CE, the forces behind the First Jewish Revolt took control of Machaerus, and held it until 72 CE, when a siege secured the defeat of the local Jewish forces.

At the end of the last attempts at Jewish independence and the destruction of Judea, the Romans joined the province of Judea (which already included Samaria) to the Galilee to form a new province, which they called Syria Palaestina.[5] Following the Roman conquest, the lands on both sides of the Jordan River with its Jewish inhabitants came under the control and decrees of subsequent Roman emperors and Arab caliphates.

Over the centuries, the Jewish population within present-day Jordan gradually declined, until no Jews were left.[citation needed]

Ottoman rule

Under Ottoman rule (1516 - 1917 CE) the name "Palestine" disappeared as the official name of an administrative unit, as the Turks often named their (sub)provinces after the capital. Since its 1516 incorporation into the Ottoman Empire, what had been Palestine was part of the vilayet of Damascus-Syria until 1660, next to the vilayet of Saida (Sidon), This was briefly interrupted by the 7 March 1799 - July 1799 French occupation of Jaffa, Haifa, and Caesarea. On 10 May 1832 it was one of the Turkish provinces annexed by Muhammad Ali's short-lived, imperialistic Egypt (nominally still Ottoman); but in November 1840, direct Ottoman rule was restored.

British Empire

The British Balfour Declaration of 1917 endorsed the idea of a Jewish homeland in Palestine. The World Zionist Organization submitted to the Paris Peace conference of 1919 a memorandum specifying boundaries of Palestine, to be put under British Mandate and eventually to become an "autonomous Commonwealth". According to the document:

"The fertile plains east of the Jordan, since the earliest Biblical times, have been linked economically and politically with the land west of the Jordan. The country which is now very sparsely populated, in Roman times supported a great population. It could now serve admirably for colonisation on a large scale. A just regard for the economic needs of Palestine and Arabia demands that free access to the Hedjaz Railway throughout its length be accorded both Governments."[6]

From as early as 1917, the land to the east of the Jordan River, known as Transjordan, was treated separately by the British administration, who saw it as a future Arab state.[7] A formal decision to restrict the Jewish homeland to west of the Jordan was made at the Cairo conference in March 1921, and accordingly a new article was added to the draft mandate text allowing the British government to administer Transjordan separately.[7] The mandate was approved by the League of Nations in July 1922, and in September 1922 the League approved a memorandum spelling out in detail the exclusion of Transjordan from the Jewish homeland provisions.[7]

Jordan and Palestine

Following the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine of 1947, and the establishment of the state of Israel on 14 May, 1948. Jordan, then known as Transjordan, was one of the Arab countries that immediately attacked the new country. It gained control of the West Bank, and expelled its remaining Jewish population. Jordan lost the West Bank during the 1967 Six-Day War, but did not relinquish its claim to the West Bank until 1988. Jordan significantly reduced its military participation in the subsequent 1973 war against Israel. Jordan eventually signed the Israel-Jordan Treaty of Peace in 1994, normalizing relations between the two countries.

Trade and tourism

Jordan has welcomed a number of Israeli companies to open plants in Jordan. Israeli tourists, as well as Jewish citizens of other countries, visit Jordan . Jordan has no laws barring Jews from its territory as is the case in Saudi Arabia. In the year following the 1994 Israel-Jordan treaty, some 60,000 to 80,000 Israeli tourists visited Jordan. Expectations of closer relations between the countries led to a proposal to open a kosher restaurant in Amman. With a loss of Arab clientele, failure to secure kosher certification, and lack of interest among tourists, the enterprise failed.[8]

Part of the 1994 peace treaty restored political control of the 500-acre Tzofar farm fields in the Arava valley to Jordan, with the preservation of Israeli private land-use rights. This area is not subject to customs or immigration legislation. The treaty preserves this arrangement for 25 years, with automatic renewal unless either country terminates the arrangement.[9]

The Island of Peace at the confluence of the Yarmouk and Jordan Rivers is operated under a similar agreement allowing Israeli usage under Jordanian ownership.

Following the Second Intifada (2000–2005), Israeli tourism to Jordan declined greatly, as a result of anti-Israeli agitation among a wide segment of the population. In August 2008, Jordanian border officials turned back a group of Israeli tourists who were carrying Jewish religious items. According to the guards, the items posed a "security risk," even if used within the privacy of a hotel, and could not be brought into the country. In response, the tour group chose not to enter Jordan.[10]

Jews in the Arabian Peninsula

- History of the Jews in Arabia (disambiguation)

- History of the Jews in Iraq

- History of the Jews in Bahrain

- History of the Jews in Kuwait

- History of the Jews in Oman

- History of the Jews in Qatar

- History of the Jews in Saudi Arabia

- History of the Jews in the United Arab Emirates

- Yemenite Jews

See also

- Abrahamic religion

- Arab Jews

- Arab states of the Persian Gulf

- Babylonian captivity

- History of the Jews in the Arabian Peninsula

- History of the Jews under Muslim rule

- Islam and antisemitism

- Jewish exodus from Arab lands

- Jews outside Europe under Nazi occupation

- Judaism and Islam

- List of Jews from the Arab World

- Mizrahi Jews

- Transjordan (Bible)

References

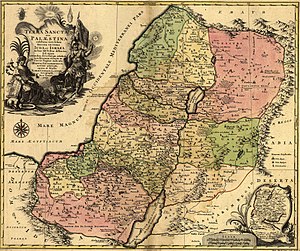

- ^ Lotter, Tobias Conrad, 1717-1777. Terra Sancta sive Palæstina exhibens...

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Josephus, "Ant." xii. 8, §§ 1, 6

- ^ ib. xiii. 9, § 1; xiv. 4, § 4

- ^ Josephus, Jewish Wars iv. 4, § 5

- ^ http://www.usd.edu/erp/Palestine/history.htm#135-337 Lehmann, Clayton Miles (May–September 1998). Palestine: History: 135–337: Syria Palaestina and the Tetrarchy

- ^ J. C. Hurewitz (1979). The Middle East and North Africa in World Politics: a documentary record. Yale University Press. p. 140.

- ^ a b c Yitzhak Gil-Har (1981). "The Separation of Trans-Jordan From Palestine". The Jerusalem Cathedra. 1: 284–313.

- ^ Ibrahim, Youssef M. (14 September 1995). "Amman Journal; Kosher in Jordan, an Idea Whose Time It Wasn't". The New York Times.

- ^ Main Points of the Israel-Jordan Peace Treaty. Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs http://www.mfa.gov.il/MFA/Peace+Process/Guide+to+the+Peace+Process/Main+Points+of+Israel-Jordan+Peace+Treaty.htm

- ^ Wagner, Matthew "Jordan bars Jews with religious items" Jerusalem Post August 14, 2008