I, Robot

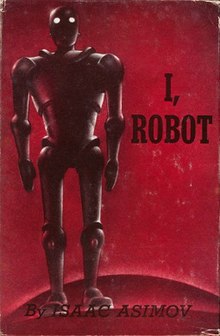

First edition cover. | |

| Author | Isaac Asimov |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Ed Cartier |

| Language | English |

| Series | Robot series |

| Genre | Science fiction |

| Publisher | Gnome Press |

Publication date | December 2, 1950 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (hardback) |

| Pages | 253 |

| Followed by | The Complete Robot |

I, Robot is a collection of science fiction short stories by American writer Isaac Asimov. The stories originally appeared in the American magazines Super Science Stories and Astounding Science Fiction between 1940 and 1950 and were then compiled into a book for stand-alone publication by Gnome Press in 1950, in an initial edition of 5,000 copies. The stories are woven together by a framing narrative in which the fictional Dr. Susan Calvin tells each story to a reporter (who serves as the narrator) in the 21st century. Although the stories can be read separately, they share a theme of the interaction of humans, robots, and morality, and when combined they tell a larger story of Asimov's fictional history of robotics.

Several of the stories feature the character of Dr. Calvin, chief robopsychologist at U.S. Robots and Mechanical Men, Inc., the major manufacturer of robots. Upon their publication in this collection, Asimov wrote a framing sequence presenting the stories as Calvin's reminiscences during an interview with her about her life's work, chiefly concerned with aberrant behaviour of robots and the use of "robopsychology" to sort out what is happening in their positronic brain. The book also contains the short story in which Asimov's Three Laws of Robotics first appear. Other characters that appear in these short stories are Powell and Donovan, a field-testing team which locates flaws in USRMM's prototype models.

The collection shares a title with the 1939 short story "I, Robot" by Eando Binder (pseudonym of Earl and Otto Binder), but is not connected to it. Asimov had wanted to call his collection Mind and Iron, and initially objected when the publisher made the title the same as Binder's. Isaac Asimov was heavily influenced by the Binder short story. In his introduction to the story in Isaac Asimov Presents the Great SF Stories (1979), Asimov wrote:

It certainly caught my attention. Two months after I read it, I began 'Robbie', about a sympathetic robot, and that was the start of my positronic robot series. Eleven years later, when nine of my robot stories were collected into a book, the publisher named the collection I, Robot over my objections. My book is now the more famous, but Otto's story was there first.

Contents

- "Introduction" (the initial portion of the framing story or linking text)

- "Robbie" (1940, 1950)

- "Runaround" (1942)

- "Reason" (1941)

- "Catch That Rabbit" (1944)

- "Liar!" (1941)

- "Little Lost Robot" (1947)

- "Escape!" (1945)

- "Evidence" (1946)

- "The Evitable Conflict" (1950)

Reception

The New York Times described I, Robot as "an exciting science thriller [which] could be fun for those whose nerves are not already made raw by the potentialities of the atomic age."[1] Also reviewing the Gnome release, P. Schuyler Miller recommended the collection "For puzzle situations, for humor, for warm character, [and] for most of the values of plain good writing."[2]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2013) |

Publication history

- New York: Gnome Press (trade paperback "Armed Forces Edition", 1951)

- New York: Grosset & Dunlap (hardcover, 1952)

- London: Grayson (hardcover, 1952)

- British SF Book Club (hardcover, 1954)

- New York: Signet Books (mass market paperback, 1956)

- New York: Doubleday (hardcover, 1963)

- London: Dobson (hardcover, 1967)

- ISBN 0-449-23949-7 (mass market paperback, 1970)

- ISBN 0-345-31482-4 (mass market paperback, 1983)

- ISBN 0-606-17134-7 (prebound, 1991)

- ISBN 0-553-29438-5 (mass market paperback, 1991)

- ISBN 1-4014-0039-6 (e-book, 2001)

- ISBN 1-4014-0038-8 (e-book, 2001)

- ISBN 0-553-80370-0 (hardcover, 2004)

- ISBN 91-27-11227-6 (hardcover, 2005)

- ISBN 0-7857-7338-X (hardcover)

- ISBN 0-00-711963-1 (paperback, UK, new edition)

- ISBN 0-586-02532-4 (paperback, UK)

Dramatic adaptations

Television

At least three of the short stories from I, Robot have been adapted for television. The first was a 1962 episode of Out of this World hosted by Boris Karloff called "Little Lost Robot" with Maxine Audley as Susan Calvin. Two short stories from the collection were made into episodes of Out of the Unknown: "The Prophet" (1967), based on "Reason"; and "Liar!" (1969).[3] The 12th episode of the USSR science fiction TV series This Fantastic World, filmed in 1987 and entitled Don't Joke with Robots, was based on works by Aleksandr Belyaev and Fredrik Kilander as well as Asimov's "Liar!" story.[4]

Both the original and revival series of The Outer Limits include episodes named "I, Robot"; however, both are adaptations of the Earl and Otto Binder story of that name and are unconnected with Asimov's work.

Films

Harlan Ellison's screenplay (1978)

In the late 1970s, Warner Brothers acquired the option to make a film based on the book, but no screenplay was ever accepted. The most notable attempt was one by Harlan Ellison, who collaborated with Asimov himself to create a version which captured the spirit of the original. Asimov is quoted as saying that this screenplay would lead to "the first really adult, complex, worthwhile science fiction movie ever made."

Ellison's script builds a framework around Asimov's short stories that involves a reporter named Robert Bratenahl tracking down information about Susan Calvin's alleged former lover Stephen Byerly. Asimov's stories are presented as flashbacks that differ from the originals in their stronger emphasis on Calvin's character. Ellison placed Calvin into stories in which she did not originally appear and fleshed out her character's role in ones where she did. In constructing the script as a series of flashbacks that focused on character development rather than action, Ellison used the film Citizen Kane as a model.[5]

Although acclaimed by critics, the screenplay is generally considered to have been unfilmable based upon the technology and average film budgets of the time.[5] Asimov also believed that the film may have been scrapped because of a conflict between Ellison and the producers: when the producers suggested changes in the script, instead of being diplomatic as advised by Asimov, Ellison "reacted violently" and offended the producers.[6] The script was serialized in Asimov's Science Fiction magazine in late 1987, and eventually appeared in book form under the title I, Robot: The Illustrated Screenplay, in 1994 (reprinted 2004, ISBN 1-4165-0600-4).

2004 film

The film I, Robot, starring Will Smith, was released by Twentieth Century Fox on July 16, 2004 in the United States. Its plot incorporates elements of "Little Lost Robot,"[7] some of Asimov's character names and the Three Laws. However, the plot of the movie is mostly original work adapted from a screenplay Hardwired by Jeff Vintar completely unlinked to Asimov's stories[7] and has been compared to Asimov's The Caves of Steel, which revolves around the murder of a roboticist (although the rest of the film's plot is not based on that novel or other works by Asimov).

Radio

BBC Radio 4 aired an audio drama adaptation of five of the I, Robot stories on their 15 Minute Drama in 2017, dramatized by Richard Kurti and starring Hermione Norris.

These also aired in a single program on BBC Radio 4 Extra as Isaac Asimov's 'I, Robot': Omnibus.[13]

Video game

Prequels

Mickey Zucker Reichert was asked to write three[14] prequels of I, Robot by Asimov's estate, because she is a science fiction writer with a medical degree. She first met Asimov when she was 23, although she did not know him well.[15] She is the first female writer to be authorized to write stories based on Asimov's novels;[15] follow-ups to his Foundation series were written by Gregory Benford, Greg Bear and David Brin.[14] The prequels were ordered by Berkley Books,[14] and consist of:

- I Robot: To Protect (2011)

- I Robot: To Obey (2013)

- I Robot: To Preserve (2016)

Popular culture references

In 2004 The Saturday Evening Post said that I, Robot's Three Laws "revolutionized the science fiction genre and made robots far more interesting than they ever had been before."[16] I, Robot has influenced many aspects of modern popular culture, particularly with respect to science fiction and technology. One example of this is in the technology industry. The name of the real-life modem manufacturer named U.S. Robotics was directly inspired by I, Robot. The name is taken from the name of a robot manufacturer ("United States Robots and Mechanical Men") that appears throughout Asimov's robot short stories.[17]

Many works in the field of science fiction have also paid homage to Asimov's collection.

An episode of the original Star Trek series, "I, Mudd" (1967) which depicts a planet of androids in need of humans references "I, Robot." Another reference appears in the title of a Star Trek: The Next Generation episode, "I, Borg" (1992), in which Geordi La Forge befriends a lost member of the Borg collective and teaches it a sense of individuality and free will.

An episode of The Simpsons entitled "I D'oh Bot" (2004) has Professor Frink build a robot named "Smashius Clay" (also named "Killhammad Aieee") that follows all three of Asimov's laws of robotics.

The animated science fiction/comedy Futurama makes several references to I, Robot. The title of the episode "I, Roommate" (1999) is a spoof on I, Robot although the plot of the episode has little to do with the original stories.[18] Additionally, the episode "The Cyber House Rules" included an optician named "Eye Robot" and the episode "Anthology of Interest II" included a segment called "I, Meatbag."[citation needed] Also in "Bender's Game" (2008) the psychiatrist is shown a logical fallacy and explodes when the assistant shouts "Liar!" a la "Liar!". Leela once told Bender to "cover his ears" so that he would not hear the robot-destroying paradox which she used to destroy Robot Santa (he punishes the bad, he kills people, killing is bad, therefore he must punish himself), causing a total breakdown; additionally, Bender has stated that he is Three Laws Safe.

The positronic brain, which Asimov named his robots' central processors, is what powers Data from Star Trek: The Next Generation, as well as other Soong type androids. Positronic brains have been referenced in a number of other television shows including Doctor Who, Once Upon a Time... Space, Perry Rhodan, The Number of the Beast, and others.

Author Cory Doctorow has written a story called "I, Robot" as homage to Asimov,[19] as well as "I, Row-Boat", both released in the short-story collection Overclocked: Stories of the Future Present. He has also said, "If I return to this theme, it will be with a story about uplifted cheese sandwiches, called 'I, Rarebit.'"[20]

Other cultural references to the book are less directly related to science fiction and technology. The 1977 album I Robot, by The Alan Parsons Project, was inspired by Asimov's I, Robot. In its original conception, the album was to follow the themes and concepts presented in the short story collection. The Alan Parsons Project were not able to obtain the rights in spite of Asimov's enthusiasm; he had already assigned the rights elsewhere. Thus, the album's concept was altered slightly although the name was kept (minus comma to avoid copyright infringement).[21] The 2002 electronica album by experimental artist Edman Goodrich (known, at times, to operate under the aliases of "je, le roi!" and "The Ghost Quartet") shares the title of I, Robot, and is heavily influenced by Asimovian themes. The 2009 album, I, Human, by Singaporean band Deus Ex Machina draws heavily upon Asimov's principles on robotics and applies it to the concept of cloning.[22]

The Indian science fiction film Endhiran, released in 2010, refers to Asimov's three laws for artificial intelligence for the fictional character Chitti: The Robot. When a scientist takes in the robot for evaluation, the panel enquires whether the robot was built using the Three Laws of Robotics.

Footnotes

- ^ "Realm of the Spacemen," The New York Times Book Review, February 4, 1951

- ^ "Book Reviews", Astounding Science Fiction, September 1951, pp.124–25

- ^ IMDb list of actresses that have played Susan Calvin.

- ^ Template:Ru icon State Fund of Television and Radio Programs Archived September 8, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Weil, Ellen; Wolfe, Gary K. (2002). Harlan Ellison: The Edge of Forever. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press. p. 126. ISBN 0-8142-0892-4.

- ^ Isaac Asimov, "Hollywood and I". In Asimov's Science Fiction, May 1979.

- ^ a b Topel, Fred (August 17, 2004). ""Jeff Vintar was Hardwired for I,ROBOT" (interview with Jeff Vintar, script writer)". Screenwriter's Utopia. Christopher Wehner. Retrieved July 30, 2014.

- ^ "Robbie, Isaac Asimov's I, Robot, 15 Minute Drama - BBC Radio 4". BBC. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- ^ "Reason, Isaac Asimov's I, Robot, 15 Minute Drama - BBC Radio 4". BBC. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- ^ "Little Lost Robot, Isaac Asimov's I, Robot, 15 Minute Drama - BBC Radio 4". BBC. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- ^ "Liar, Isaac Asimov's I, Robot, 15 Minute Drama - BBC Radio 4". BBC. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- ^ "The Evitable Conflict, Isaac Asimov's I, Robot, 15 Minute Drama - BBC Radio 4". BBC. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- ^ "Isaac Asimov's 'I, Robot': Omnibus - BBC Radio 4 Extra". BBC. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- ^ a b c "Fantasy author to write new 'Isaac Asimov' novels". October 29, 2009. Retrieved November 9, 2014.

- ^ a b "Area author continues works of Isaac Asimov". Kalona News. May 25, 2011. Retrieved November 9, 2014.

- ^ Kreiter, Ted. "Revisiting The Master Of Science Fiction". Saturday Evening Post. 276 (6): 38. ISSN 0048-9239.

- ^ U.S. Robotics Press Kit, 2004, p3 PDF format

- ^ M. Keith Booker (2006). Drawn to Television: Prime-Time Animation from the Flintstones to Family Guy. Westport, Conn.: Praeger. p. 122. ISBN 0-275-99019-2.

- ^ Doctorow, Cory. "Cory Doctorow's Craphound.com". http://www.craphound.com/?p=189 (retrieved April 27, 2008)

- ^ Doctorow, Cory. "Cory Doctorow's Craphound.com". http://www.craphound.com/?p=1676 (retrieved April 27, 2008)

- ^ Official Alan Parsons Project website Archived February 18, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Reviews". Live 4 Metal. Retrieved October 13, 2011.

References

- Chalker, Jack L.; Mark Owings (1998). The Science-Fantasy Publishers: A Bibliographic History, 1923–1998. Westminster, MD and Baltimore: Mirage Press, Ltd. p. 299.

| Series: |

Followed by: |

|---|---|

| Robot series Foundation Series |

The Rest of the Robots |