John Huske

Lieutenant-General John Huske | |

|---|---|

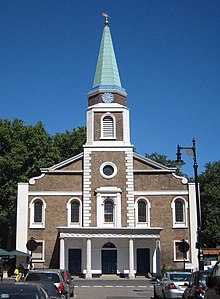

Grosvenor Chapel, in Audley Street where Huske was buried | |

| Born | 1692 Newmarket, Suffolk |

| Died | 18 January 1761 Albemarle Street, London |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1708-1749 |

| Rank | Lieutenant General September 1747 |

| Unit | Colonel, 23rd Foot, later Royal Welch Fusiliers 1743–1761 |

| Commands | Governor, Hurst Castle Governor of Sheerness 1745-1748 Governor of Jersey 1749-1761 |

| Battles / wars | War of the Spanish Succession Malplaquet War of the Austrian Succession Dettingen Lauffeld Jacobite rising of 1745 Falkirk Muir Culloden |

| Relations | Ellis Huske (1700-1755), brother; American journalist and author John Huske (1724-1773), nephew; MP for Maldon 1763-1773 †[1] John Huske (?-1792); representative to 1788 and 1789 North Carolina Constitution Convention[2] |

Lieutenant General John Huske (ca 1692 – 18 January 1761) was a British military officer, whose active service began in 1707 during the War of the Spanish Succession, included the Jacobite rising of 1745 and ended in 1748.

During his early career, he was a close associate of the Earl of Cadogan and the Duke of Marlborough. Between 1715 and 1720, he was also employed as a British political and diplomatic agent, particularly involved in anti-Jacobite operations.

He never married and died in London on 18 January 1761.

Life

John Huske was born in 1692, eldest son of John (1651-1703) and Mary Huske (1656-?); little is known of his background, other than that the family were members of the minor gentry in Newmarket, Suffolk. He never married and his younger brothers Ellis (1700-1755) and Richard (died July 1760), predeceased him.[3] On his death in January 1761, most of his estate was left to friends and servants, including £5,000 (2019; £1 million) to his head groom, £3,000 to his valet and £100 to the 'poor of Newmarket.'[4]

He bequeathed minor amounts to his nieces and nephews, with the notable exception of Ellis' son John (1724-1773). Described by historian Lewis Namier as a 'tough, unscrupulous adventurer,' he was born in Portsmouth, New Hampshire and came to England in 1748. Elected MP for Maldon in 1763, he worked closely with Charles Townshend, author of the 1765 Stamp Act, one of the issues leading to the 1775 American Revolution. Accused of embezzling £30,000–£40,000, he fled to Paris in 1769, where he died in 1773.[5]

Career

Huske began his military career as an ensign in Caulfield's Regiment of Foot, a unit recruited in Ireland and sent to garrison Barcelona in May 1706.[6] The date of his commission is given as August, 1707, several months after the regiment and four others had been officially disbanded. A Parliamentary committee held in April showed it arrived in Spain significantly understrength.[7]

As a result, Huske's early movements are somewhat obscure but in March 1709, he was commissioned cornet in the 5th Dragoon Guards, based in Flanders. The 5th Dragoons was commanded by William Cadogan, close aide to the Duke of Marlborough and the connection was of great benefit to Huske's career.[8]

In March 1709, he became an ensign in the Foot Guards, although this did not imply service; only 16 of its nominal 24 companies were actually formed and Huske remained with his original unit.[9] Under the practice known as double-ranking, Guards officers held a second and higher army rank; a Guards ensign ranked as a regular army captain. The commission purchase system meant money was important for a military career but these had to be approved. A Guards commission automatically gave its holder higher precedence in determining promotions and since they were rarely disbanded, it was a way to retain competent but poor officers.[10]

The political struggle between British Tories and Whigs led to Marlborough's resignation in 1712; accompanied by Cadogan, he went into self-imposed exile in Europe but returned in August 1714 when George I succeeded Queen Anne. In January 1715, Huske became a captain in the 15th Foot; in July, he also received a captain's commission in the Coldstream Guards, making him a Lieutenant-Colonel in the regular army.[11]

In the same month, the Whig administration secretly approved the detention of six Members of Parliament, including Sir William Wyndham, a Jacobite leader in South-West England. The warrants were not executed until August, when the Earl of Mar launched the 1715 Rising in Scotland. Wyndham's father-in-law, the Duke of Somerset, was a member of the government and his brother-in-law the Earl of Hertford, colonel of Huske's regiment, the 15th Foot.[12]

This may explain why Huske was sent to arrest Wyndham; when he arrived at his home near Minehead, Wyndham promised to accompany him after saying goodbye to his wife but then escaped through a window.[13] Given the prevailing social convention that a gentleman's word was his bond, this was felt to reflect badly on Wyndham, who was recaptured soon after. Huske escaped blame and joined Cadogan in the Dutch Republic, where he helped arrange the transport of 6,000 Dutch troops to Scotland.[14]

Marlborough suffered the first of a series of strokes in May 1716; he remained Master-General of the Ordnance or army commander until his death in 1722, but Cadogan took over many of his duties. This gave Huske a more prominent diplomatic role and he took part in a number of anti-Jacobite intelligence operations; during the 1719 Rising, he worked with diplomat Charles Whitworth to transfer five Dutch battalions to Britain, although it collapsed before this became necessary.[15]

Huske and the Earl of Albemarle accompanied Cadogan on his 1720 diplomatic mission to Vienna, the beginning of a long friendship between the two. It was a high-profile assignment seeking to create an anti-Russian alliance and end Swedish support for the Jacobites.[16] Cadogan became Master-General when Marlborough died in 1722 but his involvement in the financial scandal known as the South Sea bubble led to the loss of most of his political influence. Huske was appointed lieutenant-governor of Hurst Castle in July 1721 but Cadogan's death in 1726 and the slow pace of promotion in peace time meant that by 1739, he was still a major in the Coldstream Guards.[17]

When the War of the Austrian Succession began in December 1740, he became Colonel of the 32nd Foot, then based in Scotland; Huske apparently 'put a stop to the abuse and brutality of its Highland recruits.'[18] The regiment was transferred to Flanders and served under George II at Dettingen in June 1743. Famous as the last time a British monarch personally led troops in battle, Huske was badly wounded leading his brigade.[19]

As a reward, in July 1743 he was promoted major general and appointed colonel of the 23rd Foot or Royal Regiment of Welch Fusiliers, while he also became Governor of Sheerness in 1745.

1745 Rebellion

The 1745 Rising began in August and in September, Huske landed in Newcastle with 6,000 German and Dutch troops, captured at Tournai in June and released on condition they did not fight against the French.[20] After a long and distinguished career, George Wade, commander in the North, was no longer fit for service, the Dutch and Germans refused to march without being paid in advance and one observer wrote 'I never saw so ill a conducted Machine as Our Army.'[21]

The Jacobites invaded England on 8 November, captured Carlisle and continued south before turning back at Derby on 6 December; leaving a garrison at Carlisle, they re-entered Scotland on 21st. Cumberland and the main field army besieged Carlisle and Henry Hawley was appointed commander in Scotland, with Huske as his deputy.[22]

After arriving in Edinburgh, on 13 January Huske and 4,000 men moved north to relieve Blakeney, garrison commander at Stirling Castle, then besieged by the Jacobites. Hawley and an additional 3,000 men met up with him at Falkirk on 16 January, where the main Jacobite force was waiting. Hawley overestimated both the vulnerability of Highland infantry to cavalry and seriously underestimated their numbers and fighting qualities. This contributed to his defeat at Falkirk Muir on 17 January, a battle that started late in the afternoon in failing light and heavy snow and was marked by confusion on both sides.[23]

The government dragoons charged the Jacobite right but were repulsed in disorder, scattering their own infantry who also fled; the regiments under Huske held their ground, allowing the bulk of the army to withdraw in good order. They were helped by confusion among the Jacobite commanders and by the Highlanders diverting to loot the baggage train.[24]

Cumberland arrived in Edinburgh on 30 January and resumed the advance while the Jacobites retreated to Inverness. At the Battle of Culloden on 16 April, Huske commanded the reserves on the government left, which took the weight of the Jacobite charge. The front rank gave ground, but Huske brought his troops onto their flank, exposing the Highlanders to volleys of fire at close range from three sides. Unable to respond, they broke and fled, the battle lasting less than forty minutes.[25]

Jacobite losses were estimated as between 1,200 and 1,500 dead, many killed during the pursuit that followed; this was a standard part of any 18th-century battle, and troops that held together, such as the French regulars, were far less vulnerable than those who scattered like the Highlanders.[26] What was not common was the widely reported killing of Jacobite wounded after the battle, allegedly on the orders of senior government officers. Whether this included Huske is unclear but during his period at Fort Augustus as commander of 'pacification' operations, he proposed a £5 bounty for the head of every rebel brought into camp. While this was rejected, author and historian John Prebble refers to the killings as 'symptomatic of the army's general mood and behaviour.'[27]

Post-1745 Career and legacy

Huske was promoted lieutenant-general for his service during the Rising and returned to Flanders, where his regiment suffered heavy casualties in the Allied defeat at Lauffeld in July 1747.[28] Shortly afterwards, Cumberland sent him to inspect and report back on the Dutch town of Bergen op Zoom, then besieged by the French; it surrendered in September.[29]

The combination of these events and financial exhaustion led to the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748 and this end of Huske's active military career. While he remained colonel, he did not accompany the 23rd when it became part of the garrison of Minorca in 1755; in June 1756, it surrendered to the French in the opening battle of the Seven Years' War and was given free passage to Gibraltar. Appointed Governor of Jersey in 1749, he appears to have visited the island only once, in 1751;[30] his will left £2,000 to Charles d'Auvergne, who deputised for him in Jersey.[31]

He owned a small estate in Ealing, then outside London, and rented a house in Albemarle Street, London, where he died on 18 January 1761. As instructed in his will, he was buried without ceremony in Grosvenor Chapel, Audley Street, London and his coffin placed next to that of Albemarle, his long-time friend and colleague who died in 1754.[32]

References

- ^ Namier, Lewis (ed), Brooke, J (ed) (1964). he History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1754-1790. Boydell & Brewer.

{{cite book}}:|last1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Powell (ed), William (1988). Dictionary of North Carolina Biography. Univ of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1469629032.

{{cite book}}:|last1=has generic name (help) - ^ London Magazine: Or, Gentleman's Monthly Intelligencer..., Volume 29. 1760. p. 379.

- ^ Nichols, John (1761). The Gentleman's magazine; Volume 31. E Cave. p. 22.

- ^ Spain, Jonathan (2004). Huske, John (Online ed.). Oxford DNB. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/14262.

- ^ Rumble, A (ed), Dimmer, C (ed) (2006). Calendar of State Papers 1705-1706, Volume IV; Of the Reign of Anne. Boydell Press. p. 15.

{{cite book}}:|last1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Scouller, R.E (1976). "The Peninsula in the War of the Spanish Succession". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. 54 (220): 241. JSTOR 44224209.

- ^ Dalton, Charles (1904). English army lists and commission registers, 1661-1714 Volume VI. Eyre & Spottiswood. p. 30.

- ^ Dalton, Volume VI p.318

- ^ Springman, Michael (2008). The Guards Brigade in the Crimea (2014 ed.). Pen and Sword. p. 11. ISBN 978-1844156788.

- ^ Mckinnon, Daniel (1833). Origin and Services of the Coldstream Guards, Volume 2. Richard Bentley. p. 455.

- ^ Lord, Evelyn (2004). The Stuart Secret Army: The Hidden History of the English Jacobites. Pearson. p. 69. ISBN 978-0582772564.

- ^ Boyer, Mr (1716). Quadriennium Annæ Postremum; Or the Political State of Great Britain Volume 10. pp. 330–336.

- ^ Sedgwick, Romney (1970). William Cadogan (ca 1671-1726) in The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1715-1754. HMSO.

- ^ Sedgwick, Romney (1970). Charles Whitworth (ca 1675-1725) in The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1715-1754. HMSO.

- ^ Hartley, Janet (2002). Charles Whitworth: Diplomat in the Age of Peter the Great. Routledge. p. 173. ISBN 978-0754604808.

- ^ Yonge, William (1740). A List of the Colonels, Lieutenant Colonels, Majors, Captains, Lieutenants and Ensigns, of His Majesty's Forces. HMSO. p. 14.

- ^ "Major John MacDonald – Redcoat or Rebel?". Rogart Heritage. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ^ Royle, Trevor (2016). Culloden; Scotland's Last Battle and the Forging of the British Empire. Little, Brown. p. 63. ISBN 978-1408704011.

- ^ Lord Elcho, David (author), Charteris, Edward Evan (ed) (1907). A short account of the affairs of Scotland : in the years 1744, 1745, 1746. David Douglas, Edinburgh. p. 256.

{{cite book}}:|last1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ O'Hara, James. "Letter from [J. O'Hara] 2nd Baron Tyrawly, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, to Henry Pelham; 11 Nov. 1745". University of Nottingham; Manuscripts & Special Collections. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- ^ Riding, Jacqueline (2016). Jacobites: A New History of the 45 Rebellion. Bloomsbury. pp. 342–343. ISBN 978-1408819128.

- ^ Royle, pp. 64-65

- ^ Historic Environment Scotland. "Battle of Falkirk II (BTL9)". Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- ^ Riding, pp. 424-425

- ^ Riding, p. 427

- ^ Prebble, John (1963). Culloden (2002 ed.). Pimlico. p. 203. ISBN 978-0712668200.

- ^ Fortescue, John H (1899). History of the British Army; Volume II. pp. 161–162.

- ^ "Huske to Chesterfield: ordered by Cumberland to inspect Bergen op Zoom and report to the army". National Archives.

- ^ "John Huske, Governor of Jersey". The Island Wiki. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ Nichols, John (1761). The Gentleman's magazine; Volume 31. E Cave. p. 22.

- ^ The General Evening Post: 8 January 1761. 8 January 1761.

Sources

- Dalton, Charles (1904). English army lists and commission registers, 1661-1714 Volume VI. Eyre & Spottiswood.

- Hartley, Janet (2002). Charles Whitworth: Diplomat in the Age of Peter the Great. Routledge. ISBN 978-0754604808.

- Lord, Evelyn (2004). The Stuart Secret Army: The Hidden History of the English Jacobites. Pearson. ISBN 978-0582772564.

- Lord Elcho, David (author), Charteris, Edward Evan (ed) (1907). A short account of the affairs of Scotland : in the years 1744, 1745, 1746. David Douglas, Edinburgh.

{{cite book}}:|last1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Mckinnon, Daniel (1833). Origin and Services of the Coldstream Guards, Volume 2. Richard Bentley.

- Nichols, John (1761). The Gentleman's magazine; Volume 31. E Cave.

- Prebble, John (1963). Culloden (2002 ed.). Pimlico. ISBN 978-0712668200.

- Riding, Jacqueline (2016). Jacobites: A New History of the 45 Rebellion. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1408819128.

- Royle, Trevor (2016). Culloden; Scotland's Last Battle and the Forging of the British Empire. Little, Brown. ISBN 978-1408704011.

- Rumble, A (ed), Dimmer, C (ed) (2006). Calendar of State Papers 1705-1706, Volume IV; Of the Reign of Anne. Boydell Press.

{{cite book}}:|last1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Scouller, R.E (1976). "The Peninsula in the War of the Spanish Succession". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. 54 (220).

- Sedgwick, Romney (1970). Charles Whitworth (ca 1675-1725) in The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1715-1754. HMSO.

- Spain, Jonathan (2004). Huske, John (Online ed.). Oxford DNB. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/14262.

- Springman, Michael (2008). The Guards Brigade in the Crimea. Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1844156788.

- Yonge, William (1740). A List of the Colonels, Lieutenant Colonels, Majors, Captains, Lieutenants and Ensigns, of His Majesty's Forces. HMSO.

- 1692 births

- 1761 deaths

- East Yorkshire Regiment officers

- 32nd Regiment of Foot officers

- British Army generals

- British Army personnel of the Jacobite rising of 1745

- British Army personnel of the War of the Austrian Succession

- British Army personnel of the Seven Years' War

- Coldstream Guards officers

- Governors of Jersey

- Royal Welch Fusiliers officers