Just price

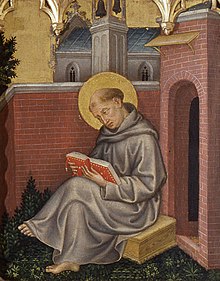

The just price is a theory of ethics in economics that attempts to set standards of fairness in transactions. With intellectual roots in ancient Greek philosophy, it was advanced by Thomas Aquinas based on an argument against usury, which in his time referred to the making of any rate of interest on loans.

| Part of a series on |

| Thomas Aquinas |

|---|

|

Unjust price: a kind of fraud

The argument against usury was that the lender was receiving income for nothing, since nothing was actually traded. Aquinas later expanded his argument to oppose any unfair earnings made in trade, basing the argument on the Golden Rule. He held that it was immoral to gain financially without actually creating something. The Christian should "do unto others as you would have them do unto you", meaning he should trade value for value. Aquinas believed that it was specifically immoral to raise prices because a particular buyer had an urgent need for what was being sold and could be persuaded to pay a higher price because of local conditions:

- If someone would be greatly helped by something belonging to someone else, and the seller not similarly harmed by losing it, the seller must not sell for a higher price: because the usefulness that goes to the buyer comes not from the seller, but from the buyer's needy condition: no one ought to sell something that doesn't belong to him.[1]

- — Summa Theologiae, 2-2, q. 77, art. 1

Aquinas would therefore condemn practices such as raising the price of building supplies in the wake of a natural disaster. Increased demand caused by the destruction of existing buildings does not add to a seller's costs, so to take advantage of buyers' increased willingness to pay constituted a species of fraud in Aquinas's view.[2]

Aquinas believed all gains made in trade must relate to the labour exerted by the merchant, not to the need of the buyer. Hence, he condoned moderate gain as payment even for unnecessary trade, provided the price were regulated and kept within certain bounds:

...there is no reason why gain [from trading] may not be directed to some necessary or even honourable end; and so trading will be rendered lawful; as when a man uses moderate gains acquired in trade for the support of his household, or even to help the needy...

Later reinterpretations of the doctrine

In Aquinas' time, most products were sold by the immediate producers (i.e. farmers and craftspeople), and wage-labor and banking were still in their infancy. The role of merchants and money-lenders was limited. The later School of Salamanca argued that the just price is determined by common estimation which can be identical with the market price -depending on various circumstances such as relative bargaining power of sellers and buyers- or can be set by public authorities[citation needed]. With the rise of Capitalism, the use of just price theory faded[citation needed]. In modern economics, interest is seen as payment for a valuable service, which is the use of the money, though most banking systems still forbid excessive interest rates[citation needed].

Likewise, during the rapid expansion of capitalism over the past several centuries the theory of the just price was used to justify popular action against merchants who raised their prices in years of dearth. The Marxist historian E. P. Thompson emphasized the continuing force of this tradition in his pioneering article on the "Moral Economy of the English Crowd in the Eighteenth Century." Other historians and sociologists have uncovered the same phenomenon in variety of other situations including peasants riots in continental Europe during the nineteenth century and in many developing countries in the twentieth. The political scientist James C. Scott, for example, showed how this ideology could be used as a method of resisting authority in "The Moral Economy of the Peasant: Subsistence and Rebellion in Southeast Asia" (1976).

Brazilian journalist and philosopher Olavo de Carvalho joined the just price of St. Thomas Aquinas with the economic theories of Böhm-Bawerk. Explaining that the medieval usurer differed to modern capitalist by the fact that in medieval society wealth was fixed (land), while in industrial society the function of money had changed completely: “At the new framework, none could accumulate money under the bed for stroke him between dawn swoon of fetishistic perversion, but I had to bet it quickly on overall growth of the economy before inflation turned it into dust. If he committed the blunder of investing it in the impoverishment of anyone else, would be investing in his own bankruptcy.”[3]

See also

- Labor theory of value

- Price

- Pricing

- Supply and demand

- History of economic thought

- Catholic social teaching

Notes

- ^ Si vero aliquis multum iuvetur ex re alterius quam accepit, ille vero qui vendidit non damnificatur carendo re illa, non debet eam supervendere. Quia utilitas quae alteri accrescit non est ex vendente, sed ex conditione ementis, nullus autem debet vendere alteri quod non est suum. . .

- ^ Aquinas, Summa Theologica, 2ª-2ae q. 77 pr.: "Deinde considerandum est de peccatis quae sunt circa voluntarias commutationes. Et primo, de fraudulentia quae committitur in emptionibus et venditionibus ..."

- ^ http://www.olavodecarvalho.org/textos/capitalismoecristianismo.htm

External links

- St Thomas Aquinas's Summa Theologiae, 2-2, q. 77 on lawful and unlawful gains in trade (Latin)

- An article discusses the Salamanca school and just price

- Another article traces the development of Just Price doctrine through the Salamanca school

| List of Marketing Topics | List of Management Topics |

| List of Economics Topics | List of Accounting Topics |

| List of Finance Topics | List of Economists |