KIF23

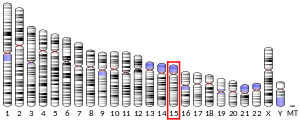

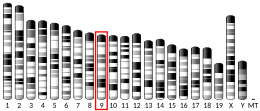

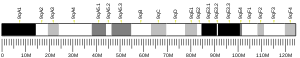

Kinesin-like protein KIF23 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the KIF23 gene.[5][6]

Function

In cell division

KIF23 (also known as Kinesin-6, CHO1/MKLP1, C. elegans ZEN-4 and Drosophila Pavarotti) is a member of kinesin-like protein family. This family includes microtubule-dependent molecular motors that transport organelles within cells and move chromosomes during cell division. This protein has been shown to cross-bridge antiparallel microtubules and drive microtubule movement in vitro. Alternate splicing of this gene results in two transcript variants encoding two different isoforms, better known as CHO1, the larger isoform and MKLP1, the smaller isoform.[6] KIF23 is a plus-end directed motor protein expressed in mitosis, involved in the formation of the cleavage furrow in late anaphase and in cytokinesis.[5][7][8] KIF23 is part of the centralspindlin complex that includes PRC1, Aurora B and 14-3-3 which cluster together at the spindle midzone to enable anaphase in dividing cells.[9][10][11]

In neurons

In neuronal development KIF23 is involved in the transport of minus-end distal microtubules into dendrites and is expressed exclusively in cell bodies and dendrites.[12][13][14][15][16] Knockdown of KIF23 by antisense oligonucleotides and by siRNA both cause a significant increase in axon length and a decrease in dendritic phenotype in neuroblastoma cells and in rat neurons.[14][15][17] In differentiating neurons, KIF23 restricts the movement of short microtubules into axons by acting as a "brake" against the driving forces of cytoplasmic dynein. As neurons mature, KIF23 drives minus-end distal microtubules into nascent dendrites contributing to the multi-polar orientation of dendritic microtubules and the formation of their short, fat, tapering morphology.[17]

Interactions

KIF23 has been shown to interact with:

Mutation and diseases

KIF23 has been implicated in the formation and proliferation of GL261 gliomas in mouse.[23]

References

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000137807 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000032254 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ a b Nislow C, Lombillo VA, Kuriyama R, McIntosh JR (Nov 1992). "A plus-end-directed motor enzyme that moves antiparallel microtubules in vitro localizes to the interzone of mitotic spindles". Nature. 359 (6395): 543–7. doi:10.1038/359543a0. PMID 1406973.

- ^ a b "Entrez Gene: KIF23 kinesin family member 23".

- ^ Hutterer A, Glotzer M, Mishima M (December 2009). "Clustering of centralspindlin is essential for its accumulation to the central spindle and the midbody". Curr. Biol. 19 (23): 2043–9. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2009.10.050. PMC 3349232. PMID 19962307.

- ^ Hornick JE, Karanjeet K, Collins ES, Hinchcliffe EH (May 2010). "Kinesins to the core: The role of microtubule-based motor proteins in building the mitotic spindle midzone". Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 21 (3): 290–9. doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2010.01.017. PMC 3951275. PMID 20109573.

- ^ Neef R, Klein UR, Kopajtich R, Barr FA (February 2006). "Cooperation between mitotic kinesins controls the late stages of cytokinesis". Curr. Biol. 16 (3): 301–7. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2005.12.030. PMID 16461284.

- ^ a b Douglas ME, Davies T, Joseph N, Mishima M (May 2010). "Aurora B and 14-3-3 coordinately regulate clustering of centralspindlin during cytokinesis". Curr. Biol. 20 (10): 927–33. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2010.03.055. PMC 3348768. PMID 20451386.

- ^ Glotzer M (January 2009). "The 3Ms of central spindle assembly: microtubules, motors and MAPs". Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10 (1): 9–20. doi:10.1038/nrm2609. PMC 2789570. PMID 19197328.

- ^ Sharp DJ, Kuriyama R, Essner R, Baas PW (October 1997). "Expression of a minus-end-directed motor protein induces Sf9 cells to form axon-like processes with uniform microtubule polarity orientation". J. Cell Sci. 110 (19): 2373–80. PMID 9410876.

- ^ Sharp DJ, Yu W, Ferhat L, Kuriyama R, Rueger DC, Baas PW (August 1997). "Identification of a microtubule-associated motor protein essential for dendritic differentiation". J. Cell Biol. 138 (4): 833–43. doi:10.1083/jcb.138.4.833. PMC 2138050. PMID 9265650.

- ^ a b Yu W, Sharp DJ, Kuriyama R, Mallik P, Baas PW (February 1997). "Inhibition of a mitotic motor compromises the formation of dendrite-like processes from neuroblastoma cells". J. Cell Biol. 136 (3): 659–68. doi:10.1083/jcb.136.3.659. PMC 2134303. PMID 9024695.

- ^ a b Yu W, Cook C, Sauter C, Kuriyama R, Kaplan PL, Baas PW (August 2000). "Depletion of a microtubule-associated motor protein induces the loss of dendritic identity". J. Neurosci. 20 (15): 5782–91. PMID 10908619.

- ^ Xu X, He C, Zhang Z, Chen Y (February 2006). "MKLP1 requires specific domains for its dendritic targeting". J. Cell Sci. 119 (Pt 3): 452–8. doi:10.1242/jcs.02750. PMID 16418225.

- ^ a b Lin S, Liu M, Mozgova OI, Yu W, Baas PW (October 2012). "Mitotic motors coregulate microtubule patterns in axons and dendrites". J. Neurosci. 32 (40): 14033–49. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3070-12.2012. PMC 3482493. PMID 23035110.

- ^ Boman AL, Kuai J, Zhu X, Chen J, Kuriyama R, Kahn RA (October 1999). "Arf proteins bind to mitotic kinesin-like protein 1 (MKLP1) in a GTP-dependent fashion". Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton. 44 (2): 119–32. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0169(199910)44:2<119::AID-CM4>3.0.CO;2-C. PMID 10506747.

- ^ Guse A, Mishima M, Glotzer M (April 2005). "Phosphorylation of ZEN-4/MKLP1 by aurora B regulates completion of cytokinesis". Curr. Biol. 15 (8): 778–86. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2005.03.041. PMID 15854913.

- ^ Li J, Wang J, Jiao H, Liao J, Xu X (March 2010). "Cytokinesis and cancer: Polo loves ROCK'n' Rho(A)". J Genet Genomics. 37 (3): 159–72. doi:10.1016/S1673-8527(09)60034-5. PMID 20347825.

- ^ Pohl C, Jentsch S (March 2008). "Final stages of cytokinesis and midbody ring formation are controlled by BRUCE". Cell. 132 (5): 832–45. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.012. PMID 18329369.

- ^ Kurasawa Y, Earnshaw WC, Mochizuki Y, Dohmae N, Todokoro K (August 2004). "Essential roles of KIF4 and its binding partner PRC1 in organized central spindle midzone formation". EMBO J. 23 (16): 3237–48. doi:10.1038/sj.emboj.7600347. PMC 514520. PMID 15297875.

- ^ Takahashi S, Fusaki N, Ohta S, Iwahori Y, Iizuka Y, Inagawa K, Kawakami Y, Yoshida K, Toda M (February 2012). "Downregulation of KIF23 suppresses glioma proliferation". J. Neurooncol. 106 (3): 519–29. doi:10.1007/s11060-011-0706-2. PMID 21904957.

Further reading

- Miki H, Setou M, Kaneshiro K, Hirokawa N (June 2001). "All kinesin superfamily protein, KIF, genes in mouse and human". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98 (13): 7004–11. doi:10.1073/pnas.111145398. PMC 34614. PMID 11416179.

- Lee KS, Yuan YL, Kuriyama R, Erikson RL (December 1995). "Plk is an M-phase-specific protein kinase and interacts with a kinesin-like protein, CHO1/MKLP-1". Mol. Cell. Biol. 15 (12): 7143–51. PMC 230970. PMID 8524282.

- Deavours BE, Walker RA (July 1999). "Nuclear localization of C-terminal domains of the kinesin-like protein MKLP-1". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 260 (3): 605–8. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1999.0952. PMID 10403813.

- Mishima M, Kaitna S, Glotzer M (January 2002). "Central spindle assembly and cytokinesis require a kinesin-like protein/RhoGAP complex with microtubule bundling activity". Dev. Cell. 2 (1): 41–54. doi:10.1016/S1534-5807(01)00110-1. PMID 11782313.

- Kuriyama R, Gustus C, Terada Y, Uetake Y, Matuliene J (March 2002). "CHO1, a mammalian kinesin-like protein, interacts with F-actin and is involved in the terminal phase of cytokinesis". J. Cell Biol. 156 (5): 783–90. doi:10.1083/jcb.200109090. PMC 2173305. PMID 11877456.

- Kitamura T, Kawashima T, Minoshima Y, Tonozuka Y, Hirose K, Nosaka T (December 2001). "Role of MgcRacGAP/Cyk4 as a regulator of the small GTPase Rho family in cytokinesis and cell differentiation". Cell Struct. Funct. 26 (6): 645–51. doi:10.1247/csf.26.645. PMID 11942621.

- Obuse C, Yang H, Nozaki N, Goto S, Okazaki T, Yoda K (February 2004). "Proteomics analysis of the centromere complex from HeLa interphase cells: UV-damaged DNA binding protein 1 (DDB-1) is a component of the CEN-complex, while BMI-1 is transiently co-localized with the centromeric region in interphase". Genes Cells. 9 (2): 105–20. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2443.2004.00705.x. PMID 15009096.

- Matuliene J, Kuriyama R (July 2004). "Role of the midbody matrix in cytokinesis: RNAi and genetic rescue analysis of the mammalian motor protein CHO1". Mol. Biol. Cell. 15 (7): 3083–94. doi:10.1091/mbc.E03-12-0888. PMC 452566. PMID 15075367.

- Liu X, Zhou T, Kuriyama R, Erikson RL (July 2004). "Molecular interactions of Polo-like-kinase 1 with the mitotic kinesin-like protein CHO1/MKLP-1". J. Cell Sci. 117 (Pt 15): 3233–46. doi:10.1242/jcs.01173. PMID 15199097.

- Beausoleil SA, Jedrychowski M, Schwartz D, Elias JE, Villén J, Li J, Cohn MA, Cantley LC, Gygi SP (August 2004). "Large-scale characterization of HeLa cell nuclear phosphoproteins". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101 (33): 12130–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.0404720101. PMC 514446. PMID 15302935.

- Jin J, Smith FD, Stark C, Wells CD, Fawcett JP, Kulkarni S, Metalnikov P, O'Donnell P, Taylor P, Taylor L, Zougman A, Woodgett JR, Langeberg LK, Scott JD, Pawson T (August 2004). "Proteomic, functional, and domain-based analysis of in vivo 14-3-3 binding proteins involved in cytoskeletal regulation and cellular organization". Curr. Biol. 14 (16): 1436–50. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2004.07.051. PMID 15324660.

- Rush J, Moritz A, Lee KA, Guo A, Goss VL, Spek EJ, Zhang H, Zha XM, Polakiewicz RD, Comb MJ (January 2005). "Immunoaffinity profiling of tyrosine phosphorylation in cancer cells". Nat. Biotechnol. 23 (1): 94–101. doi:10.1038/nbt1046. PMID 15592455.

- Benzinger A, Muster N, Koch HB, Yates JR, Hermeking H (June 2005). "Targeted proteomic analysis of 14-3-3 sigma, a p53 effector commonly silenced in cancer". Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 4 (6): 785–95. doi:10.1074/mcp.M500021-MCP200. PMID 15778465.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Zhu C, Bossy-Wetzel E, Jiang W (July 2005). "Recruitment of MKLP1 to the spindle midzone/midbody by INCENP is essential for midbody formation and completion of cytokinesis in human cells". Biochem. J. 389 (Pt 2): 373–81. doi:10.1042/BJ20050097. PMC 1175114. PMID 15796717.

External links

- Baas, Peter. "Peter Baas Lab". Research Lab.

- Kuriyama, Ryoko. "Ryoko Kuriyama Lab". Research Lab.

- Glotzer, Michael. "Michael Glotzer Lab". Research Lab.

- Mishima, Masanori. "Masanori Mishima". Research Lab.

- Barr, Francis. "Francis Barr Lab". Research Lab.