Legal profession in Thailand

| Legal profession in Thailand | |

|---|---|

| Legal | |

| The Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand 2007 Lawyer's Act B.E. 2528 | |

| Legal System | |

| Based on Civil law system Code of law influenced by codified systems such as France, Japan, Germany and also customary laws of Thailand | |

| Judicial system | |

|

The legal profession in Thailand has three categories: judges, public prosecutors, and lawyers. Legal practice is based upon the civil law system with the code of law influenced by other codified systems such as France, Germany and Japan as well as customary laws of Thailand.[1]

History of Legal Practice in Thailand

The ancient origins of Thai Law was based on the Hindu code of Manu. During the Sukhothai period (1238–1350 AD),[2] there was no system of Justice since the King was "the Fountain of Justice" who alone settled disputes between the people.

During the Ayutthaya Period (1351–1767 AD),[3] the first semblance of a legal system emerged. The law code was the Royal Stone Inscription[4] which was formulated from a set of rules derived from the Kings’ decisions[5] in the Court of Law.[Note 1] Although the law code[Note 2] allowed for people to be represented in court for civil and criminal matters, the lawyer’s work was limited. He could not be involved in the examination of witnesses before the court and was mainly concerned with writing plaints and filing them before the court.[6]

When Thailand was invaded by Burma in 1767, collections of law were partially destroyed.[7] King Rama I ordered to have all laws rectified and written into law books called "the Law of the three Great Seals" which remained in force for the next 103 years. Despite this development, the role of the lawyer remained static and constricted. This could be attributed to simple way of life of the society where majority did not resort to the law to settle their disputes.[7]

Foreign influence

In 1827, Thailand, which had trade relations with Western countries, was forced by England to amend its rules and regulation.[Note 3] Adopting an open door policy, King Rama IV (reigned 1851–1868>[8] tried to reform the Thai law and judiciary to make it acceptable to the Western countries.

Modernisation and Development of Legal Practice

In continuation of King Rama IV’s efforts, his son, King Rama V (reigned 1868–1910)[8] appointed Royal Commissioners to reform existing laws. These efforts revolutionized the law and modernized the judiciary. A new court system was set up between 1894–97.[9] The King no longer judged cases himself although decisions of the Supreme Court of Appeal were still made under his name.[10]

In 1892, the Ministry of Justice was established and its Minister, Prince Raphi,[Note 4] was appointed to unify the judiciary. He set up the first law school in Thailand.[Note 5] Moreover, he also reorganized the Thai court system under the Law on the Organization of 1908.

Bar Association in Thailand and Practising Lawyers’ Act

In 1914, the Bar Association in Thailand was formed and was the first Thai lawyers’ organization. Following this, the first Lawyers’ Act was passed and it legitimized the legal profession and practice in Thailand.

Evolving Role of Legal Practice

As seen from above, the role of the legal practice has evolved tremendously over the years. In the early years, it could be said that the power of judiciary and lawmaking was solely vested with the King. Today, although the King is the Head of the Thai Nation, his legislative power is exercised with the consent of the National Assembly and the power of the judiciary is vested in the Courts. The lawyer’s role has also been legitimized with the establishment of law schools and with the Lawyers’ Act.[11]

The legal education system

Starting legal education

Legal education in Thailand is an undergraduate programme. To enter, it is compulsory to take the National University Entrance Examination conducted by the Ministry of University Affairs. Entry is determined by academic records from upper secondary school, test scores, interviews and physical examinations.[12]

Choosing a place for legal education

One can choose between Private universities, Public universities and Open universities.[13]

Open universities are typically for rural dwellers who are interested in legal studies but are unable to attend other universities. Education by open universities is often off-campus and on a correspondence basis.

The Institute of Legal Education of Thai Bar Association[14] was set up in 1948 to increase legal knowledge among law practitioners.[15]

Different types of certification/qualifications

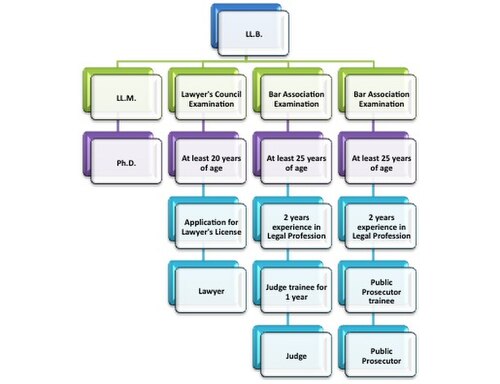

There is the 4-year Bachelor of Laws (LL.B.) course;[16] the 1-year Master of Laws (LL.M.) programme,[Note 6] and the doctoral programme (Ph.D),[Note 7] typically a 3-year course.

Curriculum

Lectures are conducted in Thai, and faculty members are graduates of foreign law schools. Students are required to choose an area of specialisation in their third year of study, either Business Law, Public Law, International Law, or Civil and Criminal Law.[Note 8]

General criticism regarding Thai law schools include the excessive rote learning, memorisation of laws and the ineffective lecture-style of teaching which discourages discussion. Moreover, scant attention is given to subjects like international law and investment subjects because of a lack of qualified teachers on these topics in the country.[18]

Recent reforms

The government’s desire to promote foreign direct investment in Thailand has prompted a reform of local university curriculum to meet the changing international demands.[Note 9]

The curriculum is also changing from a more traditional to a more student-centered one where law lecturers prepare their lesson plans with case studies, activities and effective evaluation.

Since becoming an ASEAN member in 2008, the ASEAN Charter has positively impacted the Thai legal education. Many courses are now taught in English and there is a significant increase in partnership courses with overseas universities.[19] It is now also a requirement to be competent in foreign language and IT for graduates to be able to transcend national boundaries in communication and conduct legal research at the international level.[20]

Necessary Requirements for Practice

As set out in the Lawyer’s Act, lawyers have to fulfill a set of conditions to obtain a license.[21] In addition to the LL.B., law graduates are required to be Thai nationals, cannot be a government official, and must pass an exam for a lawyer license.[22] On passing the Lawyers Council examination, one can apply for permission to practice law.[23]

Division of Roles in the Profession

The legal profession in Thailand is divided among various types of professionals. The professionals involved are "First and Second class lawyers" (distinction has since been abolished), "Notaries" and "Foreign Practitioners".

First and Second Class Lawyers

Prior to 1985, practising lawyers in Thailand were divided into two classes.[24] First-class lawyers were law graduates while second-class lawyers held a diploma in law and passed an examination held by the Bar Association.

The main distinction was that first-class lawyers could practice throughout the country while second-class lawyers could only practice in ten provinces specified in their licenses. Since the Lawyers' Act passed in 1985,[25] this distinction has been removed and those registered under the Act have the right of audience in all courts throughout the country.

Notaries

In Thailand, public documents,[26] such as birth and marriage certificates need to be verified, witnessed and certified by a notary, a public official who legalizes documents by his hand and official seal.[27]

To become a notary, a Thai lawyer is required to complete a legal training course by the Lawyer’s Council of Thailand.[28]

There have been reported instances of unlicensed notaries in Thailand, and the public has been advised to be cautious in dealing with notaries.

Foreign legal practitioners

Foreigners are not allowed to formally practice law.[29] Instead foreigners work as "consultants", mostly on transnational cases.

Foreign practitioners provide a valuable service to their clients which the local lawyers cannot. Moreover, they impart valuable knowledge on foreign laws to their Thai colleagues.[30]

Appointment of Judges

Requirements

The main criteria for law graduates intending to be judges are: At least 25 years of age, an L.L.B., a Barrister-at-Law degree from the Bar Institute, and two years’ experience in the legal profession.[Note 10] Judge trainees then undergo training courses and serve as judges’ assistants for not less than one year.

Types of Judges

There are four types of judges in the Thai system – career judges, senior judges, associate judges and Datoh justices.[31]

Career judges

The process to becoming a career judge involves five stages.[31]

First Stage: Meet general qualifications for judge-trainee, such as: Thai nationality, 25 years of age and being a member of the Thai Bar Association.

Second Stage: Fulfill one of three methods to become a judge-trainee:

- Open Examination: For LL.B. holders with at least two years of legal experience.

- Knowledge Test: For LL.B or other qualification holders without two years of legal experience but satisfying other criteria.

- Special Selection: For academics and ranking government officials who possess excellent knowledge in the law.

Third Stage: Undergo at least one year of training as a judge-trainee.

Fourth Stage: Approval by the Judicial Service Commission and tendering application to the King.

Fifth Stage: Receiving royal appointment by the King.

Senior Judges

Unlike Commonwealth jurisdictions which value the experience and wisdom of older judges, Senior Judges in Thailand are viewed very differently. When judges reach 60 years old, they are restricted to duties in the lower Courts of First Instance, and cannot hold the position of Chief Justice.

In addition, judges reaching 60 must be reappointed to office, and can only hold office till the age of 70. To be reappointed, judges must:

- Be approved by the Judicial Service Commission;

- Be tendered for Royal appointment; and

- Pass a physical assessment at 65 years old.

Layman judges

Layman judges are not legally trained. They typically comprise people with experience or expertise in areas such as Family, Labor and Intellectual Property. Having laymen working with career judges helps provide more varied opinions in deciding cases.

Layman judges are selected by the Judicial Service Commission and do not hold permanent positions .[31]

Kadi

Kadis (Qadi) are experts in Islam. They work with career judges to decide family law cases in certain provinces.[32] A Kadi ensures that the court complies with Islamic principles.

A Kadi is required to be above 30 years old, possess good command of Thai, and have knowledge in Islamic laws regarding family and succession.[32]

Judicial Service Commission

The Judicial Service Commission plays a crucial role in the appointment of judges. It screens all potential candidates before their tender to the King, and holds power over the removal, promotions, salary increments and punishment of judges.[33]

The Judicial Service Commission consists of mainly members of the judiciary:[34] the Supreme Court President, 12 members from all Court levels and 2 officers elected by the Senate.

Appointment of Public Prosecutors

The Constitution sets out the powers and duties of public prosecutors.[35]

Requirements

The main criteria for Law graduates intending to be public prosecutors are: Thai nationality, an LL.B, and passing the Thai Bar Association examination.[36]

Public Prosecutors Committee

The Public Prosecutors Committee[35] has crucial role in the appointment of Public Prosecutors. It is charged with:

- Appointing and removing the Prosecutor General upon approval of the Senate.[35]

- Approving the appointment, promotion, salary increments, transfers, removal and punishment of public prosecutors.[37]

Role of the legal profession in Thailand

Different role in a non-litigious environment

Thai lawyers have a very different role from their Western counterparts in dealing with civil wrongs and disputes. In Thailand, parties tend to avoid legal proceedings because of its confrontational nature. Instead, they rely on mutual understanding to reach a solution.[38]

This non-litigious environment stems from the Thai culture, which accords great value to the importance of harmonious societal relationships, and places communal interests above individual interests. As such, dispute resolutions which avoid conflict and embody the spirit of tolerance are perceived as the more appropriate approach.[39]

Hence, lawyers are drawn to roles in non-judicial approaches such as mediation and arbitration, which allows disputing parties more flexibility.[40]

Political involvement

Judiciary

The Thai judiciary plays a key role in Thai politics. On 30 May 2007, the Constitutional Court of Thailand dissolved the Thai Tak Thai Party, the incumbent ruling party under former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, due to international law violations.

In the wake of the 2011 elections, the Democrat legal team also initiated legal proceedings to challenge and dissolve the Puea Thai Party.[41]

Lawyers

In light of the violence against "Red Shirt" anti-government protestors in April and May 2010, lawyers have demanded a full investigation into the deaths of more than 80 civilians. They have filed a notice to the International Criminal Court (ICC) alleging human rights violations.[42]

The Human Rights Committee of the Lawyers Council of Thailand

The Human Rights Committee of the Lawyers Council of Thailand regularly comments on the issues of human rights that plague Thailand and even propose strategies the government can follow.

In June 2011, the committee released a report that assessed the conditions under which the government could send back Burmese refugees in accordance with the requirements of international law and existing treaties and agreements.[43]

In September 2011, the committee submitted a statement to the PM, the Secretary-General of the National Security Council, the Minister of Social Development and Human Security, the Minister of Defense, and Commissioner-General of the Royal Thai Police on certain strategies they can adopt to handle the problem of human trafficking of the Rohingya people.[44]

Lawyers as Educators

The Thongbai Thongbao Foundation

The Thongbai Thongbao Foundation was founded in 1990 by Thongbai Thongbao, who was a well-known human rights lawyer from Mahasarakham pronvince, Thailand.[45] They provide both legal aid and education to various sectors of the society, and they visit about 30 villages and districts annually.[45] Their objective is to ensure that Thai people are aware of their rights and know how to take proper legal action. Aspects of the law that affect people in everyday situations, such as law on marriages, law on loans and mortgages, labour law and human rights law, are taught and discussed at their training sessions.[45]

The International Thai Foundation / COMMUNITY LEGAL CENTRE

The International Thai Foundation was founded in 2012 with the Thai Ministry of Interior, Kor Tor 2266. It provides legal advice and representation to those whom are disadvantaged, poor, disabled, DFNs and vulnerable so they may access justice. It established a Community Legal Centre in Chiang Mai.

Social and economic concerns

Social position of lawyers

Today, the legal profession is no longer exclusive to the upper classes.[46] Entry into the Thai law schools is based on a merit system and middle class students are generally not restricted by university fees.[Note 11]

First, the rise of the middle class, or the chonchan klaang,[46] saw an increase in the number of Thai students in higher education, from 16.1% in 1990 to 44.6% in 2009. Second, the average Thai household in 2009 made 250,836 Baht annually,[48] compared to typical law school fees of 23,570 Baht per academic year.[Note 12]

This resulted in a 25 times increase in the number of lawyers in Thailand – in 1960, there were about 2,000 lawyers for a population of 23 million; in 2008, there were about 54,000 lawyers in a population of 60 million.[49]

Economic significance of lawyers

The legal profession in Thailand is traditionally a Thai-dominated profession because foreigners are not allowed to formally practice law.[29] This can be viewed as a form of control over the legal profession,[50] suggesting the government’s intention to preserve local dominance.

However, Thailand’s embrace of globalization has made transnational legal relations unavoidable. Thailand’s rapid development caused a shortage of Thai lawyers possessing expertise in specialized areas of law.[Note 13]

This has led to a unique situation in reality, where many foreign lawyers work in Thailand but under the guise of "business consultants".[52] Proposals have been made reform,[53] but it remains to be seen if the Thai government will relax requirements for foreign lawyers.

See also

- Law of Thailand

- Legal education

- Outline of Thailand

- Index of Thailand-related articles

- Education in Thailand

- List of universities and colleges in Thailand

- Law school

- Civil law (legal system)

Notes

- ^ Set up by King Borom Trailokanat at which cases were heard and administration of justice was carried out was set in the Grand Palace, close to the building in which the King daily presided over his Council.

- ^ One such law was the Law on Procedures on Admission of Plaints, which allowed for specified classes of people to be represented in court.

- ^ Most significantly, the 'Bowring treaty' which brought unequal judiciary was signed, where the English had no obligation to Thai law and judiciary.

- ^ The son of King Rama V who graduated from Oxford University.

- ^ Which saw its very first class of nine lawyers in 1897.

- ^ A prior LL.B. is usually a requirement for admission.

- ^ An in-depth research paper is usually required.

- ^ This is a course requirement at Chulalongkorn University.[17]

- ^ The country is seeking to ready itself for a flow of foreign investment into Thailand under the scheme of free and fair trade promoted by the WTO, which Thailand has become a party to.

- ^ Such as a court clerk, assistant court clerk, probation officer, official receiver, public prosecutor, practising lawyer, or other government legal officer.

- ^ For example, see law school fees of Chulalongkorn University[47]

- ^ The benchmark used is Thammasat University's Law Programme fees.

- ^ Such as petrochemicals, securities and takeovers.[51]

References

- ^ Baker & McKenzie, Bangkok Office, Doing Business in Thailand: Legal Brief 2001.

- ^ Patit P Mishra, The History of Thailand (ABC-CLIO,2010) at xiv.

- ^ Chris Baker, Christopher J Baker, P Phaonpachit, A History of Thailand (Cambridge University Press, 2nd Ed, 2009) at xv.

- ^ ASEAN Law Association, "The Judicial System in Thailand: An Outlook for a New Century" at p60 <http://www.aseanlawassociation.org/docs/Judicial_System_in_Thailand.pdf> (accessed 10 September 2011).

- ^ Bunnag, Marut, Aakesson, Preben A. F., "The Legal System in Thailand" Revised 8/96 9a Mod. Legal Sys. Cyclopedia 9A.30.1 at 9A.30.8. These precedents became known as "The Rajasattham", which was a digest of royal decisions.

- ^ Bunnag, Marut, Aakesson, Preben A. F., "The Legal System in Thailand" Revised 8/96 9a Mod. Legal Sys. Cyclopedia at 9A.30.32.

- ^ a b ASEAN Law Association, "The Judicial System in Thailand: An Outlook for a New Century" at p. 62 <http://www.aseanlawassociation.org/docs/Judicial_System_in_Thailand.pdf> (accessed 10 September 2011).

- ^ a b Clark D Nehr, Modern Thai Politics: From Village to Nation. A Collection of Readings (Schenkman Publishing Company, 1976) at p8.

- ^ Bunnag, Marut, Aakesson, Preben A. F., "The Legal System in Thailand" Revised 8/96 9a Mod. Legal Sys. Cyclopedia 9A.30.13.

- ^ H R H Prince Chula Chakrabongse, "Lords of Life: A History of the Kings of Thailand, D.D. Books, Bangkok, Thailand (1960) at 241.

- ^ Lawyers' Act B.E. 2528 (1985).

- ^ Triamanuruck, Phongpala, Chaiyasuta, "Overview of Legal Systems in the Asia-Pacific Region: Thailand" <http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1004&context=lps_lsapr&sei- redir=1#search=%22Overview%20Legal%20Systems%20Asia-Pacific%20Region%3A%20Thailand%22> at p5. (accessed on 8 September 2011).

- ^ Iam Chaya-ngam, Sukhothai Thammathirat Open University, Thailand <http://www.egyankosh.ac.in/bitstream/123456789/25046/1/Unit-3.pdf> (accessed 10 September 2011).

- ^ The Thai Bar website <"Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-09-03. Retrieved 2011-09-11.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)> (accessed 10 September 2011). - ^ Charunun Sathitsuksomboon, "Thailand's Legal System: Requirements, Practice, and Ethical Conduct" <http://asialaw.tripod.com/articles/charununlegal8.html> (accessed 10 September 2011).

- ^ ASEAN Law Association, "The Judicial System in Thailand: An Outlook for a New Century" at p. 69 <http://www.aseanlawassociation.org/docs/Judicial_System_in_Thailand.pdf> (accessed 10 September 2011).

- ^ Chuerboonchai and Srivanit, " Challenges to Legal Education in A Changing Landscape : The Case of Thailand" ( 22–25 November 2006) at p7 < http://www.aseanlawassociation.org/docs/w3_thai.pdf> (accessed on 11 September 2011)

- ^ Professor Samrieng Mekkriengkrai, "Legal Education Reform in Thailand" at pp1–2 <http://www.iaslsnet.org/meetings/teaching/papers/Mekkriengkrai.pdf[permanent dead link]> (accessed 10 September 2011).

- ^ Thanitcul, " ASEAN Charter and Legal education in Thailand" (20 August 2009) at p7<http://www.aseanlawassociation.org/10GAdocs/Thailand1.pdf> (accessed on 11 September 2011).

- ^ Professor Samrieng Mekkriengkrai, "Legal Education Reform in Thailand" at p. 3 <http://www.iaslsnet.org/meetings/teaching/papers/Mekkriengkrai.pdf[permanent dead link]> (accessed 10 September 2011).

- ^ Lawyers' Act B.E. 2528 s 35 (1985).<http://www.imolin.org/doc/amlid/Thailand_Lawyers%20Act.pdf>. (accessed 10 September 2011)

- ^ Bunnag, Marut, Aakesson, Preben A. F., "The Legal System in Thailand" Revised 8/96 9a Mod. Legal Sys. Cyclopedia 9A.30.26.

- ^ Tilleke & Gibbins, "Thailand Legal Basics" Tilleke & Gibbins International Ltd. at p5 (21 September 2009) <"Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-09-12. Retrieved 2011-09-11.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)> (accessed 10 September 2011). - ^ Lawyers' Act B.E. 2475 (1985).

- ^ Lawyers' Act B.E. 2528 s 84 (1985).

- ^ Hague Convention (1961) Abolishing the Requirements of Legalisation for Foreign Public Documents <http://www.hcch.net/index_en.php?act=conventions.text&cid=41> (accessed 9 September 2011).

- ^ Suwan Buacharern, "Notary Public in Thailand" <http://www.suwatlaw.com/NotaryPublicThailand.doc>.

- ^ Lawyer's Council of Thailand website <http://www.lawyerscouncilor.th/[permanent dead link]> (accessed 9 September 2011).

- ^ a b Lawyers Act B.E. 2528 s 35.<http://www.imolin.org/doc/amlid/Thailand_Lawyers%20Act.pdf> (accessed 10 September 2011)

- ^ Suchint Chaimunkalanont, "Cross-Border Legal Services in ASEAN Under WTO: A Thai Perspective" <http://www.aseanlawassociation.org/docs/w2_thai.pdf> (accessed 9 September 2011).

- ^ a b c Thai Courts of Justice website, "The Judiciary of Thailand" <"Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-08-20. Retrieved 2011-09-11.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)> (accessed 10 September 2011). - ^ a b Rules of Appointing and Holding Senior Judge Position Act, B.E. 2542 (1999).

- ^ ASEAN Law Association, "The Judicial System in Thailand: An Outlook for a New Century" at p. 54 <http://www.aseanlawassociation.org/docs/Judicial_System_in_Thailand.pdf> (accessed 10 September 2011).

- ^ The Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand 2007 s 221.

- ^ a b c The Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand 2007 s 225.

- ^ Regulation of Public Prosecutor Officers Act B.E. 2521 (1978).

- ^ ASEAN Law Association, "The Judicial System in Thailand: An Outlook for a New Century" at p. 55 <http://www.aseanlawassociation.org/docs/Judicial_System_in_Thailand.pdf> (accessed 10 September 2011).

- ^ Ted L. McDorman, "The Teaching of the Law of Thailand" 11 Dalhousie LJ 915 1987–1988 at 921.

- ^ Ted L. McDorman, "The Teaching of the Law of Thailand" 11 Dalhousie LJ 915 1987–1988 at 922.

- ^ The Nation website, "The Constitutional Tribunal disbands Thai Rak Thai" (30 May 2007) <http://www.nationmultimedia.com/2007/05/30/headlines/headlines_30035646.php> (accessed 9 September 2011).

- ^ Aman Kakar, "Thailand opposition lawyers challenge election" in Jurist (10 July 2011) ,http://jurist.org/paperchase/2011/07/thailand-opposition-lawyers-challenge-election.php> (accessed 11 September 2011).

- ^ The Nation/Asia One Network website, "Lawyer files case with International Criminal over red shirts" (1 February 2011) <http://www.asiaone.com/News/Latest+News/Asia/Story/A1Story20110201-261470.html> (accessed 11 September 2011).

- ^ Karen News website, "Repatriation raises many questions and no answers" (13 June 2006) <http://karennews.org/2011/06/repatriation-raises-many-questions-and-no-answers.html/> (accessed 11 September 2011).

- ^ Prachatai website, "The Lawyers Council of Thailand urges the government to tackle Rohingya traffickign organizations" (9 February 2011) <http://www.prachatai.com/english/node/2300> (accessed 11 September 2011).

- ^ a b c Asia-Pacific Human Rights Information Center website, "Thailand: The Thongbai Thongpao Experience" <http://www.hurights.or.jp/archives/human_rights_education_in_asian_schools/sectiosn2/2000/03/thailand-the-thongbai-thongpao-experience.html[permanent dead link]> (accessed 11 September 2011).

- ^ a b Funatsu, Kagoya, "The middle classes in Thailand: The Rise of the Urban Intellectual Elite and their Social Consciousness" <http://www.ide.go.jp/English/Publish/Periodicials/De/pdf/03_02_07.pdf[permanent dead link]> )accessed 10 September 2011).

- ^ http://www.reg.chula.ac.th/fee1.html

- ^ 2009 Average Monthly Household Income: Whole Kingdom (Thailand), CEIC data.

- ^ Frank Munger, "Globalization, Investing in Law, and the Careers of Lawyers for Social Cause: Taking on Rights in Thailand" 53 NYL Sch L Rev 745 at 747.

- ^ Richard Abel, "Comparative Sociology of Legal Professions" 1985 Am B Found Res J 1 1985.

- ^ Patrick Stewart, "Have Thai Lawyers Got The Market Tied Up?" International Financial Law Review April 1993.

- ^ Suchint Chaimungkalanont, "Cross-Border Legal Services in Asean Under WTO: A Thai Perspective" at p. 84.

- ^ Suchint Chaimungkalanont, "Cross-Border Legal Services in Asean Under WTO: A Thai Perspective" at p. 86.