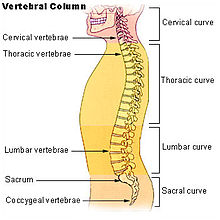

Lordosis

The term lordosis refers to the normal inward lordotic curvature of the lumbar and cervical regions of the spine.[1] Excessive curvature of the lower back is known as lumbar hyperlordosis, commonly called hollow back or saddle back (after a similar condition that affects some horses). A major feature of lumbar hyperlordosis is a forward pelvic tilt, resulting in the pelvis resting on top of the thighs. Curvature in the opposite convex direction, in the thoracic and sacral regions is termed kyphotic. When this curvature is excessive it is called kyphosis or hyperkyphosis.

Physiological lumbar lordosis

Normal lordotic curvatures, also known as secondary curvatures, results in a difference in the thickness between the front and back parts of the intervertebral disc. Lordosis may also increase at puberty sometimes not becoming evident until the early or mid-20s.

Lordosis in the human spine makes it easier for humans to bring the bulk of their mass over the pelvis. This allows for a much more efficient walking gait than that of other primates, whose inflexible spines cause them to resort to an inefficient forward leaning "bent-knee, bent-waist" gait. As such, lordosis in the human spine is considered one of the primary physiological adaptations of the human skeleton that allows for human gait to be as energetically efficient as it is.[2]

Mating position

Lordosis in a sexual context is the naturally occurring position for sexual receptivity in non-primate mammalian females (including cats, mice, and rats). The lordosis position is facilitated by the appropriate sensory input, such as touch or smell. For example, in female hamsters, when they are in the correct hormonal state there are areas on the flank that, when touched by the male, facilitate lordosis.[3] The term is also used to describe mounting behavior in male mammals.[citation needed]

Brain function

Several brain areas are known to be important for the regulation of lordosis, including the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus (VMN). The activity of the VMN in the regulation of lordosis is estrogen-dependent and when it is lesioned lordosis is abolished. Displays of lordosis can be affected by exposure to stress during puberty.[4] [5] Specifically, stress can suppressed the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis and therefore decrease concentrations of gonadal hormones. Consequently, these reductions in exposure to gonadal hormones around puberty can result in decreases in sexual behavior in adulthood, including displays of lordosis.[4]

It has been suggested that this article should be split into a new article titled Lumbar hyperlordosis. (discuss) (September 2016) |

Lumbar hyperlordosis

This section needs more reliable medical references for verification or relies too heavily on primary sources. (September 2016) |  |

| Lordosis | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Rheumatology, medical genetics |

Lumbar hyperlordosis is a condition that occurs when the lumbar region (lower back) experiences stress or extra weight and is arched to point of muscle pain or spasms. Lumbar lordosis is a common postural position where the natural curve of the lumbar region of the back is slightly or dramatically accentuated. Commonly known as swayback, it is common in dancers.[6] Imbalances in muscle strength and length are also a cause, such as weak hamstrings, or tight hip flexors (psoas).[citation needed]

Other health conditions and disorders can cause hyperlordosis. Achondroplasia (a disorder where bones grow abnormally which can result in short stature as in dwarfism), Spondylolisthesis (a condition in which vertebrae slip forward) and osteoporosis (the most common bone disease in which bone density is lost resulting in bone weakness and increased likelihood of fracture) are some of the most common causes of lordosis. Other causes include obesity, kyphosis (spine curvature disorder in which the thoracic curvature is abnormally rounded), discitits (an inflammation of the intervertebral disc space caused by infection) and benign juvenile lordosis.[7] Other factors may also include those with rare diseases, as is the case with Ehlers Danlos Syndrome (EDS), where hyper-extensive and usually unstable joints (e.g. joints that are problematically much more flexible, frequently to the point of partial or full dislocation) are quite common throughout the body. With such hyper-extensibility, it is also quite common (if not the norm) to find the muscles surrounding the joints to be a major source of compensation when such instability exists.

Excessive lordotic curvature – lumbar hyperlordosis, is also called hollow back, and saddle back [by whom?]; swayback usually refers to a nearly opposite postural misalignment that can initially look quite similar.[8][9] Common causes of lumbar hyperlordosis include tight low back muscles, excessive visceral fat, and pregnancy. Rickets, a vitamin D deficiency in children, can cause lumbar lordosis.

Signs and symptoms

Although lordosis gives an impression of a stronger back, incongruently it can lead to moderate to severe lower back pain. The most problematic symptom is that of herniated disc where the dancer has put so much strain on their back from hyperlordosis, that the discs between the vertebrae have been damaged or have ruptured. Technical problems with dancing such as difficulty in the positions of attitude and arabesque can be a sign of weak iliopsoas. Tightness of the iliopsoas results in a dancer having difficulty lifting their leg into high positions. Abdominal muscles being weak and the rectus femoris of the quadriceps being tight are signs that improper muscles are being worked while dancing which leads to lumbar hyperlordosis. The most obvious signs of lumbar hyperlordosis is lower back pain in dancing and pedestrian activities as well as having the appearance of a swayed back. All of these are signs that damage is being done, and preventative action needs to take place.[10]

Causes

Possible etiologies that lead to the condition of Lumbar hyperlordosis are the following:

Diagnosis

Measurement and diagnosis of lumbar lordosis can be difficult. Obliteration of vertebral end-plate landmarks by interbody fusion may make the traditional measurement of segmental lumbar lordosis more difficult. Because the L4-L5 and L5-S1 levels are most commonly involved in fusion procedures, or arthrodesis, and contribute to normal lumbar lordosis, it is helpful to identify a reproducible and accurate means of measuring segmental lordosis at these levels.[13][14]

A visible sign of lordosis is an abnormally large arch of the lower back and the person appears to be puffing out his or her stomach and buttocks. Precise diagnosis of lordosis is done by looking at a complete medical history, physical examination and other tests of the patient. X-rays are used to measure the lumbar curvature, bone scans are conducted in order to rule out possible fractures and infections, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is used to eliminate the possibility of spinal cord or nerve abnormalities, and computed tomography scans (CT scans) are used to get a more detailed image of the bones, muscles and organs of the lumbar region.[15]

Lordotic view

In radiology, a lordotic view is an X-ray taken of a patient leaning backwards.[16]

Treatment

Since lumbar hyperlordosis is not a fixed condition like scoliosis and kyphosis, it can be reversed.[citation needed] This can be accomplished by stretching the lower back, hip-flexors, hamstring muscles, and strengthening abdominal muscles.[citation needed]Dancers should ensure that they don't strain themselves during dance rehearsals and performances. To help with lifts, the concept of isometric contraction, during which the length of muscle remains the same during contraction, is important for stability and posture.[17]

Lumbar lordosis may be treated by strengthening the hip extensors on the back of the thighs, and by stretching the hip flexors on the front of the thighs.

Only the muscles on the front and on the back of the thighs can rotate the pelvis forward or backward while in a standing position because they can discharge the force on the ground through the legs and feet. Abdominal muscles and erector spinae can't discharge force on an anchor point while standing, unless one is holding his hands somewhere, hence their function will be to flex or extend the torso, not the hip[citation needed]. Back hyper-extensions on a Roman chair or inflatable ball will strengthen all the posterior chain and will treat lordosis. So too will stiff legged deadlifts and supine hip lifts and any other similar movement strengthening the posterior chain without involving the hip flexors in the front of the thighs. Abdominal exercises could be avoided altogether if they stimulate too much the psoas and the other hip flexors.

Controversy regarding the degree to which manipulative therapy can help a patient still exists. If therapeutic measures reduce symptoms, but not the measurable degree of lordotic curvature, this could be viewed as a successful outcome of treatment, though based solely on subjective data. The presence of measurable abnormality does not automatically equate with a level of reported symptoms.[18]

Stretches

Braces

The Boston brace is a plastic exterior that can be made with a small amount of lordosis to minimize stresses on discs that have experienced herniated discs.

In the case where Ehlers Danlos Syndrome (EDS) is responsible, being properly fitted with a customized brace may be a solution to avoid strain and limit the frequency of instability.

Tai chi

While not really a 'treatment', the art of tai chi chuan calls for adjusting the lower back curvature (as well as the rest of the spinal curvatures) through specific re-alignments of the pelvis to the thighs, it's referred to in shorthand as 'dropping the tailbone'. The specifics of the structural change are school specific, and are part of the jibengung (body change methods) of these schools. The adjustment is referred to in tai chi chuan literature as 'when the lowest vertebrae are plumb erect...' [19]

See also

Footnotes

- ^ Medical Systems: A Body Systems Approach, 2005

- ^ http://www.algoless.com/pdf/human_gait.pdf

- ^ Randy Joe Nelson (2011). An Introduction to Behavioral Endocrinology (4 ed.). pp. 319–321.

- ^ a b Jasmina Kercmar; Stuart Tobet; Gregor Majdic (2014). "Social Isolation during Puberty Affects Female Sexual Behavior in Mice". Frontiers. 8: 337. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00337. PMID 25324747.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ D. Daniels; LM. Flanagan-Cato (2000). "Social Isolation during Puberty Affects Female Sexual Behavior in Mice". J Neurobiology. 45: 1–13. PMID 10992252.

- ^ Solomon, Ruth. Preventing Dance Injuries: An Interdisciplinary Perspective. Reston , VA: American Alliance for Health, 1990.p.85

- ^ "Types of Spine Curvature Disorders". WebMD. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ^ "Sway back posture". lower-back-pain-management.com/. Retrieved 17 August 2014.

- ^ Cressey, Eric. "Strategies for Correcting Bad Posture – Part 4". EricCressey.com. Retrieved 17 August 2014.

- ^ Solomon, Ruth. Preventing Dance Injuries: An Interdisciplinary Perspective. Reston , VA: American Alliance for Health, 1990.p.122

- ^ Howse, Justin. Dance Technique and Injury Prevention. Third Edition. London: A&C Black Limited, 2000.p.193

- ^ Brinson, Peter. Fit to Dance?. London: Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, 1996.p.45

- ^ Schuler Thomas C (Oct 2004). "Segmental Lumbar Lordosis: Manual Versus Computer-Assisted Measurement Using Seven Different Techniques". J Spinal Disord Tech. 17 (5): 372–9.

- ^ Subach Brian R (Oct 2004). "Segmental Lumbar Lordosis: Manual Versus Computer-Assisted Measurement Using Seven Different Techniques". J Spinal Disord Tech. 17 (5): 372–9.

- ^ "Lordosis". Lucile Packard Children's Hospital.

{{cite web}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ "Lordotic Chest Technique".

- ^ Arnheim, Daniel D.. Dance Injuries:Their Prevention and Care. Second Edition. St. Louis, Missouri: C. V. Mosby Company, 1980.p.36

- ^ Harrison DD, et al. (1994). J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 17 (7): 454–464.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ T'ai Chi Ch'uan: A Simplified Method of Calisthenics for Health & Self Defence | By Manqing Zheng | Page 10

References

- Gabbey, Amber. "Lordosis". Healthline Networks Incorporated. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- Gylys, Barbara A.; Mary Ellen Wedding (2005), Medical Terminology Systems, F.A. Davis Company

- "Osteoporosis-overview". A.D.A.M. Retrieved 8 December 2013.