Lost Generation

| Part of a series on |

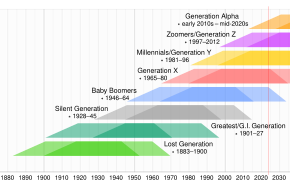

| Social generations of the Western world |

|---|

|

The Lost Generation was the generation that came of age during World War I. Demographers William Strauss and Neil Howe outlined their Strauss–Howe generational theory using 1883–1900 as birth years for this generation. The term was coined by Gertrude Stein and popularized by Ernest Hemingway, who used it as one of two contrasting epigraphs for his novel The Sun Also Rises. Hemingway credits the phrase to Gertrude Stein, who was then his mentor and patron.

In literature

In A Moveable Feast (1964), published after Hemingway's and Stein's deaths, Hemingway writes that Stein heard the phrase from a garage owner who serviced Stein's car. When a young mechanic failed to repair the car quickly enough, the garage owner shouted at the boy, "You are all a "génération perdue."[1]: 29 Stein, in telling Hemingway the story, added, "That is what you are. That's what you all are ... all of you young people who served in the war. You are a lost generation."[1]: 29 [2]

Lost in this respect means disoriented, wandering, directionless—a recognition that there was great confusion and aimlessness among the war's survivors in the early post-war years."[3]

The 1926 publication of Hemingway's The Sun Also Rises popularized the term as Hemingway used it as an epigraph. The novel serves to epitomize the post-war expatriate generation.[4]: 302 However, Hemingway later wrote to his editor Max Perkins that the "point of the book" was not so much about a generation being lost, but that "the earth abideth forever"; he believed the characters in The Sun Also Rises may have been "battered" but were not lost.[5]: 82

In his memoir A Moveable Feast, published after his death, he writes "I tried to balance Miss Stein's quotation from the garage owner with one from Ecclesiastes." A few lines later, recalling the risks and losses of the war, he adds: "I thought of Miss Stein and Sherwood Anderson and egotism and mental laziness versus discipline and I thought 'who is calling who a lost generation?'"[1]: 29–30

Literary themes

The writings of the Lost Generation literary figures tended to have common themes. These themes mostly pertained to the writers' experiences in World War I and the years following it. It is said that the work of these writers was autobiographical based on their use of mythologized versions of their lives.[6] One of the themes that commonly appears in the authors' works is decadence and the frivolous lifestyle of the wealthy.[7] Both Hemingway and Fitzgerald touched on this theme throughout the novels The Sun Also Rises and The Great Gatsby. Another theme commonly found in the works of these authors was the death of the American dream, which is exhibited throughout many of their novels.[8] It is particularly prominent in The Great Gatsby, in which the character Nick Carraway comes to realize the corruption that surrounds him.

Other uses

The term is also used in a broader context for the generation of young people who came of age during and shortly after World War I. Authors William Strauss and Neil Howe, well known for their generational theory, define the Lost Generation as the cohort born from 1883 to 1900, who came of age during World War I and the Roaring Twenties.[9] In Europe, they are mostly known as the "Generation of 1914", for the year World War I began.[10] In France, the country in which many expatriates settled, they were sometimes called the Génération au Feu, the "Generation in Flames". In Britain, the term was originally used for those who died in the war,[11] and often implicitly referred to upper-class casualties who were perceived to have died disproportionately, robbing the country of a future elite.[12] Many felt that "the flower of youth and the best manhood of the peoples [had] been mowed down,"[13] for example such notable casualties as the poets Isaac Rosenberg, Rupert Brooke, Edward Thomas and Wilfred Owen,[14] composer George Butterworth and physicist Henry Moseley.

Notable members

Sample members include Sinclair Lewis, who was the first American to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature, United States Army General George S. Patton, Russian-born composer Irving Berlin, American writer, reporter, and political commentator Walter Lippmann, Earl Warren, American theologian, ethicist, and commentator on politics Reinhold Niebuhr, Actresses Lillian Gish, Mary Pickford, and Mae West, American poet and satirist Dorothy Parker, Norman Rockwell a painter/illustrator, J. Edgar Hoover who was the first director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation of the United States, baseball player Babe Ruth whose career in Major League Baseball spanned 22 seasons from 1914 through 1935, boxers Jack Dempsey and Gene Tunney. Actors Fred Astaire, Humphrey Bogart, George Burns, James Cagney, Frederic March, Edward G. Robinson, Randolph Scott, Spencer Tracy, and Rudolph Valentino, American novelist and short story writer F. Scott Fitzgerald, American bass singer and actor who became involved with the civil rights movement Paul Robeson, Al Capone, American novelist, short story writer, and journalist Ernest Hemingway, entertainer Al Jolson, top Broadway star of the era and first star of "talking pictures", U.S. politicians Adlai Stevenson II and Henry A. Wallace, British-born film director Alfred Hitchcock, composers George Gershwin and Aaron Copland, and Italian born Nicola Sacco.[15]

Because the United States was a safe haven from the persecution, repression, and murder characteristic of fascist regimes, the United States often became a refuge for entrepreneurs, scientists (like Enrico Fermi), and creative people (like Bohuslav Martinů) who did much of their best work in America.

U.S. presidents were Harry S. Truman and Dwight D. Eisenhower. Notable international members were Clement Attlee, Vincent Auriol, Stanley Bruce, Heinrich Bruning, Marc Chagall, Charlie Chaplin, Maurice Chevalier, Ben Chifley, John Curtin, Charles de Gaulle, Morarji Desai, John Diefenbaker, Anthony Eden, Ludwig Erhard, Arthur Fadden, Frank Forde, Jacobus Johannes Fouche, Peter Fraser, Joseph Goebbels, Adolf Hitler, Sidney Holland, Nikita Khrushchev, Harold Macmillan, John McEwen, Robert Menzies, Ho Chi Minh, Joan Miro, Benito Mussolini, Walter Nash, Jawaharlal Nehru, Lester B. Pearson, Sergei Prokofiev, Vidkun Quisling, Liu Shaoqi, Charles Robberts Swart, Hideki Tojo, Lutz Graf Schwerin von Krosigk, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Plaek Phibunsongkhram, Pridi Banomyong, Mikhail Frunze, Chiang Kai-shek, Corneliu Zelea Codreanu and Mao Zedong.[16] Russian-born Golda Meir spent most of her formative years in the United States before becoming prime minister of Israel.

Sample cultural endowments are: The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald;[17] The Waste Land by T.S. Elliot; Babbitt by Sinclair Lewis; The Sound and the Fury by William Faulkner; Monkey Business (film) starring the Marx Brothers; Creed of an Advertising Man by Bruce Barton; An American in Paris by George Gershwin; The Maltese Falcon by Dashiell Hammett; The Big Sleep by Raymond Chandler; The Old Man and the Sea by Ernest Hemingway; the musical score of the ballet score Appalachian Spring by Aaron Copland; and The View from Eighty by Malcolm Cowley.[18]

Applying the birth years used by Strauss and Howe, the last known American member of the Lost Generation to live was Susannah Mushatt Jones (July 6, 1899 – May 12, 2016), while Nabi Tajima (4 August 1900 – 21 April 2018) from Japan was the last known living member of this generation overall,[19] making it fully ancestral worldwide.

See also

References

- ^ a b c Hemingway, Ernest (1996). A Moveable Feast. New York: Scribner. ISBN 0-684-82499-X.

- ^ Mellow, James R. (1991). Charmed Circle: Gertrude Stein and Company, p,273. New York: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-47982-7.

- ^ Hynes, Samuel (1990). A War Imagined: The First World War and English Culture. London: Bodley Head. p. 386. ISBN 0 370 30451 9.

- ^ Mellow, James R. (1992). Hemingway: A Life Without Consequences. New York: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-37777-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - ^ Baker, Carlos (1972). Hemingway, the writer as artist. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01305-5.

- ^ "Hemingway, the Fitzgeralds, and the Lost Generation: An Interview with Kirk Curnutt | The Hemingway Project". www.thehemingwayproject.com. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ^ "Lost Generation | Great Writers Inspire". writersinspire.org. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ^ "American Lost Generation". InterestingArticles.com. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ^ Howe, Neil; Strauss, William (1991). Generations: The History of Americas Future. 1584 to 2069. New York: William Morrow and Company. pp. 247–260. ISBN 0-688-11912-3.

- ^ Wohl, Robert (1979). The generation of 1914. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-34466-2.

- ^ "The Lost Generation: the myth and the reality". Aftermath – when the boys came home. Retrieved 6 November 2009.

- ^ Winter, J. M. (November 1977). "Britain's 'Lost Generation' of the First World War" (PDF). Population Studies. 31 (3): 449–466. doi:10.2307/2173368. JSTOR 2173368.

- ^ Rosa Luxemburg et al., "A Spartacan Manifesto, The Nation, March 8, 1919, pp. 373-374

- ^ "What was the 'lost generation'?". Schools Online World War One. BBC. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

- ^ Strauss, William; Howe, Neil (1991). Generations: the history of America's future, 1584 to 2069. William Morrow and Company. ISBN 0-688-11912-3.

- ^ Strauss, William; Howe, Neil (1991). Generations: the history of America's future, 1584 to 2069. William Morrow and Company. ISBN 0-688-11912-3.

- ^ Lapsansky-Werner, Emma J. United States History: Modern America. Boston, MA: Pearson Learning Solutions, 2011. Print. Page 238

- ^ Strauss, William; Howe, Neil (1991). Generations: the history of America's future, 1584 to 2069. William Morrow and Company. ISBN 0-688-11912-3.

- ^ Lekach, Sasha (16 September 2017). "World's oldest person dies, giving title to Japanese supercentenarian". TravelWireNews. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help)

Further reading

- Meyers, Jeffrey (1985). Hemingway: A Biography. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-42126-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Fitch, Noel Riley (1985). Sylvia Beach and the Lost Generation: A History of Literary Paris in the Twenties and Thirties. Norton. ISBN 0-393-30231-8.