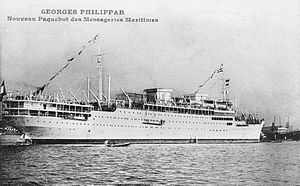

MS Georges Philippar

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Georges Philippar |

| Namesake | Georges Philippar |

| Owner | Cie des Messageries Maritimes |

| Port of registry | Marseilles |

| Builder | Soc des Ateliers et Chantiers de la Loire, St Nazaire |

| Launched | 6 November 1930 |

| Completed | January 1932 |

| Out of service | 15 May 1932 |

| Identification |

|

| Fate | Sank |

| General characteristics | |

| Tonnage | |

| Length | 542.7 ft (165.4 m) |

| Beam | 68.2 ft (20.8 m) |

| Depth | 46.9 ft (14.3 m) |

| Installed power | 3,300 NHP |

| Propulsion | 2× 10-cylinder 2S SC SA marine diesel engines; twin screws |

| Speed | 18+1⁄2 knots (34.3 km/h) |

| Crew | 347 |

Georges Philippar was an ocean liner of the French Messageries Maritimes line that was built in 1930. On her maiden voyage in 1932 she caught fire and sank in the Gulf of Aden with the loss of 54 lives.

Description

Georges Philippar was a 17,359 GRT ocean liner. She was 542.7 ft (165.4 m) long, with a beam of 68.2 ft (20.8 m) and a depth of 46.9 ft (14.3 m). She was a motor ship with two two-stroke, single cycle single-acting marine diesel engines. Each engine had 10 cylinders of 28+3⁄4 inches (730 mm) bore by 17+1⁄4 inches (440 mm) stroke and was built by Sulzer Brothers, Winterthur, Switzerland. Between them the two engines developed 3,300 NHP,[1] giving the ship a speed of 18+1⁄2 knots (34.3 km/h).[2]

History

Georges Philippar was built by Ateliers et Chantiers de la Loire, Saint-Nazaire for Compagnie des Messageries Maritimes to replace Paul Lacat, which had been destroyed by fire in December 1928.[3] She was launched on 6 November 1930.[2] On 1 December she caught fire while being fitted out.[4] Named after French Mesageries Maritimes CEO Georges Philippar, she was completed in January 1932.[2] She was registered in Marseilles.[1]

Before she started her maiden voyage, French police warned her owners that threats had been made on 26 February 1932 to destroy the ship. The outward voyage took Georges Philippar to Yokohama, Japan, without incident and she started her homeward voyage, calling at Shanghai, China and Colombo, Ceylon. Georges Philippar left Columbo with 347 crew and 518 passengers aboard. On two occasions a fire alarm went off in a store room where bullion was being stored, but no fire was found.[3] The Georges Philippar class was an innovative design, experimenting with Diesel propulsion, sporting unusual sqare section short smokestacks (whimsically dubbed flower pots by the sailors) and an extensive use of electricity, for lighting, kitchen and deck winches. Georges Philippar , the CEO of Messageries Maritimes and ship namesake created a special greek-latin term "Nautonaphtes" (Oil-powered ships) for advertising purposes as he felt that Diesel sounded too germanic for post WW1 french public.

At the time french sailor's lore considered giving a ship the name of a living person a way to attract bad luck and the practice was later discontinued. The electric plant and wiring of the Georges Philipparrelied on high voltage (220 volts) Direct current.It proved troublesome from the shipyard stage onwards with cables overheating, circuit breakers malfunctioning...and so on. It was lavishly decorated with wood panelling and sported a high gloss varnished wooden grand staircase which proved highly flammable.

Fire and loss

On 16 May while Georges Philippar was 145 nautical miles (269 km) off Cape Guardafui, Italian Somaliland,[5] a fire broke out in one of her luxury cabins occupied by Mme Valentin, wife of the CEO of an Indochina mining concern. apparently the light switch was hot and smouldering and sent sparks that ignited the luxurious wood panelling of the cabin. There was a delay in reporting the fire, which had spread by the time Captain Vicq was made aware of it. Vicq tried different firefighting tactics ( various points of sailing to keep the wind from the decks where most passengers had sought shelter), as the fire had run out of control. It has been reported that he decided to try and beach the ship on the coast of Aden and increased the ship's speed, which only made the fire burn more fiercely, but it is unsubstantiated as the engine rooms had to be evacuated and the ship was left drifting. The order to abandon ship was given and a distress signal sent.[3]

Three ships came in response. The Soviet tanker Sovietskaïa Neft rescued 420 people, who were transferred to the French passenger ship Andre Lebon and landed at Djibouti. They returned to France on the French passenger ship Général Voyron. Another 149 people were rescued by Brocklebank Line's cargo ship Mahsud and 129 were rescued by T&J Harrison's cargo ship Contractor. The two British ships landed their survivors at Aden. Mahsud also took the corpses of the 54 dead.[5] On 19 May Georges Philippar sank in the Gulf of Aden.[3] Her position was 14°20′N 50°25′E / 14.333°N 50.417°E.[2]

Albert Londres, a french star reporter, was last seen trying to escape by a porthole the cabin he was trapped in (and contained a wealth of notes and drafts from his long enquiry in China). Maurice Sadorge, the second engineering officer, tried to send him the end of a firehose from the deck above his cabin, but Londres couldn't grip it strongly enough and either fell in the sea or back in the burning cabin and died. His body was neither recovered nor identified.

Some conspiracy theories , involving either anti french action by Indochina independantist leader Nguyen Ai Quoc (better known as Ho Chi Minh) or the Japanese secret services (willing to suppress Albert Londres bombshell report of Japanese implication in drug trafficking in China to finance the Mandchukuo takeover)have been advanced but these are at best dubious as an arson was not certain at all to cause Albert Londres death. The fire was most likely caused by an electric short circuit (see further).

The sabotage rumours were further fuelled by the death of the Lang-Willar couple (whom Londres had befriended) and informed of the contents of his bombshell scoop.

While in Aden, Alfred Lang Willar made a statement that he was informed of the contents of Londres series of articles and would break the news when back in France.

Londres daily newspaper, the centre-right Excelsior of Paris hired Marcel Goulette a then famous long distance aviator, winner of the 1932 Paris to Capetown air race, to pick them up in Brindisi where the liner Esperiainward bound from Alexandria, put up on May the 25 th.

Two survivors of the fire, Mr and Mrs Alfred Isaak Lang-Willar, were killed on 25 May when the Farman 199 aircraft that was flying them from Brindisi, Italy to Marseilles crashed 70 miles (110 km) southeast of Rome.[6] The aircraft crashed in the Apennine Mountains near Veroli in cloudy weather. Goulette most probably took chances under the pressure of the incoming press scoop, and heavy debts to pay for his brand new aircraft with the hefty reward offered by Excelsior, but the insistence of the local fascist party leaders to seal the crash zone further fueled the rumours of foul play and sabotage.[7]

The November 1932 edition of La Science et la Vie carried an artist's impression of the burning ship on its front cover.[8]

Court inquiry

An official enquiry was held and Cdt Vicq, his officers and crew, along with some passengers appeared in court along with colonel Pouderoux chief paris Firefighter acting as an expert. Shipyard personnel were dissuaded to appear in court but later testified that the electric plant of the Georges Philippar had been troublesome from the start and that the Shipyard board had forecasted to postpone the ship's commission in order to correct the defects but later changed their minds under the pressure of delay penalties. Cdt Vicq downplayed the electrical troubles and frequent short circuits, only admitting trouble with the electric kitchen ovens and appliances (he had to have new heating resistances hastily manufactured in Yokohama as the original ones kept burning in succession, exhausting the ship's supply of spares). He chose to point out the faultless work of the emergency electrical generators, which he said were crucial in the comparatively low death toll. Captain's Vicq statements were probably biased by company loyalty for insurance reasons but the enquiry nevertheless concluded to a "catastrophic fire initiated by a malfunction in the high voltage DC power grid of the ship" and recommended to ban wooden fittings and panelling as much as possible in the design of future ships. The State of the art Normandiewas one of the very first ships to benefit from these new guidelines, incorporating a massively over-engineered firefighting equipment, a less troublesome Alternating current powerplant and state of the art circuit breakers.

Ironically this did not prevent Normandie from burning in New-York during WW2 as an inexperienced crew of US Coastguards had taken over from the French crew and were not familiar with the equipment.

References

- ^ a b c Lloyd's Register, Steamers and Motorships (PDF). Plimsoll Ship Data. 1932. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

- ^ a b c d "5607591". Miramar Ship Index. Retrieved 4 November 2009.

- ^ a b c d Eastlake, Keith (1998). Sea Disasters, the truth behind the tragedies. London: Greenwich Editions. p. 20. ISBN 0-86288-149-8.

- ^ "The fire in a new French liner". The Times. No. 45685. London. 2 December 1930. col C, p. 25. template uses deprecated parameter(s) (help)

- ^ a b "paquebot Georges Philippar" (in French). French Lines. Retrieved 4 November 2009.

- ^ "Flight, 8 June 1932". Flight Global. Retrieved 4 November 2009.

- ^ Cahier, Bernard (February 2012). Albert londres, terminus gardafui. Paris: Arléa. p. 219. ISBN 978-2-86959-978-9.

- ^ La Science et la Vie, November 1932 photo of cover