Macula

| Macula of retina | |

|---|---|

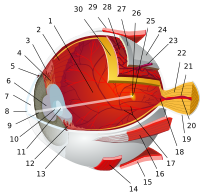

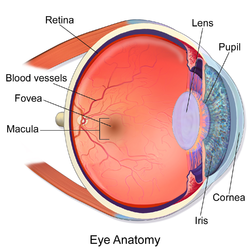

Human eye cross-sectional view, with macula near center. | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | macula lutea |

| MeSH | D008266 |

| TA98 | A15.2.04.021 |

| TA2 | 6784 |

| FMA | 58637 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The macula or macula lutea (from Latin macula, "spot" + lutea, "yellow") is an oval-shaped pigmented area near the center of the retina of the human eye. It has a diameter of around 5.5 mm. The macula is subdivided into the umbo, foveola, foveal avascular zone (FAZ), fovea, parafovea, and perifovea areas.[1] After death or enucleation (removal of the eye) the macula appears yellow, a color that is not visible in the living eye except when viewed with light from which red has been filtered. [2] The anatomical macula at 5.5 mm is much larger than the clinical macula which, at 1.5 mm, corresponds to the anatomical fovea.[3][4][5] The clinical macula is seen when viewed from the pupil, as in ophthalmoscopy or retinal photography. The anatomical macula is defined histologically in terms of having two or more layers of ganglion cells.[6]

Near its center is the fovea, a small pit that contains the largest concentration of cone cells in the eye and is responsible for central, high-resolution vision. The umbo is the center of the foveola which is located at the centre of fovea.

Structure

Color

Because the macula is yellow in colour it absorbs excess blue and ultraviolet light that enter the eye, and acts as a natural sunblock (analogous to sunglasses) for this area of the retina. The yellow color comes from its content of lutein and zeaxanthin, which are yellow xanthophyll carotenoids, derived from the diet. Zeaxanthin predominates at the macula, while lutein predominates elsewhere in the retina. There is some evidence that these carotenoids protect the pigmented region from some types of macular degeneration.

Regions

- Fovea - 1.55 mm

- Foveal Avascular Zone (FAZ) - 0.5 mm

- Foveola - 0.35 mm

- Umbo - 0.15 mm

Function

Structures in the macula are specialized for high-acuity vision. Within the macula are the fovea and foveola that both contain a high density of cones (photoreceptors with high acuity).

Clinical significance

Whereas loss of peripheral vision may go unnoticed for some time, damage to the macula will result in loss of central vision, which is usually immediately obvious. The progressive destruction of the macula is a disease known as macular degeneration and can sometimes lead to the creation of a macular hole. Macular holes are rarely caused by trauma, but if a severe blow is delivered it can burst the blood vessels going to the macula, destroying it.

Visual input from the macula occupies a substantial portion of the brain's visual capacity. As a result, some forms of visual field loss can occur without involving the macula; this is termed macular sparing. (For example, visual field testing might demonstrate homonymous hemianopsia with macular sparing.)

In the case of occipitoparietal ischemia owing to occlusion of elements of either posterior cerebral artery, patients may display cortical blindness (which, rarely, can involve blindness that the patient denies having, as seen in Anton's Syndrome), yet display sparing of the macula. This selective sparing is due to the collateral circulation offered to macular tracts by the middle cerebral artery.[7] Neurological examination that confirms macular sparing can go far in representing the type of damage mediated by an infarct, in this case, indicating that the caudal visual cortex (which is the principal recipient of macular projections of the optic nerve) has been spared. Further, it indicates that cortical damage rostral to, and including, lateral geniculate nucleus is an unlikely outcome of the infarction, as too much of the lateral geniculate nucleus is, proportionally, devoted to macular-stream processing.[8]

See also

- Cherry-red spot

- Cystoid macular edema

- Intermediate uveitis

- Macular corneal dystrophy

- Macular degeneration

- Macular edema

- Macular hypoplasia

- Macular pucker

References

- ^ "Interpretation of Stereo Ocular Angiography : Retinal and Choroidal Anatomy". Project Orbis International. Retrieved 11 October 2014.

- ^ Britton, George; Liaaen-Jensen, Synnove; Pfander, Hanspeter (29 December 2009). Carotenoids Volume 5: Nutrition and Health. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 301. ISBN 978-3-7643-7501-0. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ^ Yanoff, Myron (2009). Ocular Pathology. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 393. ISBN 0-323-04232-5. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ^ Small, R.G. (15 August 1994). The Clinical Handbook of Ophthalmology. CRC Press. p. 134. ISBN 978-1-85070-584-0. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ^ Peyman, Gholam A.; Meffert, Stephen A.; Chou, Famin; Mandi D. Conway (27 November 2000). Vitreoretinal Surgical Techniques. CRC Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-85317-585-5. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ^ Remington, Lee Ann (29 July 2011). Clinical Anatomy of the Visual System. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 314–5. ISBN 1-4557-2777-6. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ^ Helseth,, Erek. "Posterior Cerebral Artery Stroke". Medscape Reference. Medscape. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Siegel, Allan; Sapru, Hreday N. (2006). Betty Sun (ed.). Essential Neuroscience (First Revised ed.). Baltimore, Maryland: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-9121-2.

Additional images

-

The interior of the posterior half of the left eyeball.

-

A fundus photograph showing the macula as a spot to the left. The optic disc is the area on the right where blood vessels converge. The grey, more diffuse spot in the centre is a shadow artifact.

External links

![]() Media related to Macula lutea at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Macula lutea at Wikimedia Commons