Marcus Ulpius Traianus (father of Trajan)

Marcus Ulpius Traianus | |

|---|---|

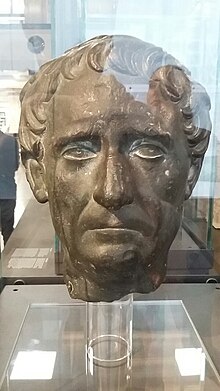

Bust at the National Museum of Serbia, Belgrade, usually identified as Trajan's father. It may instead depict Trajan himself.[1] | |

| Born | 1st century AD |

| Died | 1st century AD |

| Nationality | Roman |

| Spouse | Marcia |

| Children | Marciana and Trajan |

| Family | gens Ulpia |

Marcus Ulpius Traianus (fl. 1st century AD) was a Roman general and senator. He was the biological father of emperor Trajan.

Family

[edit]Traianus belonged to a branch of the gens Ulpia, which originally came from the Umbrian city of Tuder, but he was born and raised in the Roman colony of Italica, north of modern Santiponce and northwest of Seville, in the Roman Province of Hispania Baetica.[2] The town was founded in 206 BC by Scipio Africanus, as a settlement for wounded and invalid veterans of the wars against Carthage.[2] The Ulpii, like the Aelii and the Traii, were among the leading Roman families of the city.[2] From the latter family came the ancestors of Traianus, who intermarried with the Ulpii, giving rise to the cognomen Traianus.[2] Since the father of Traianus joined the ranks of the senators in Rome, it is very likely that his grandfather was already a member of the Roman Senate.[2] The ancestry of Traianus' mother is unknown. His sister Ulpia was the mother of Publius Aelius Hadrianus Afer, and grandmother of the emperor Hadrian. Traianus married a Roman noblewoman named Marcia.[3] She was the elder sister of Marcia Furnilla, the second wife of Titus, which enabled her to further her husband's career.[3] They had two children: a daughter, Ulpia Marciana, and a son, Marcus, the future emperor Trajan.[3]

Career

[edit]The chronology of Traianus' career is uncertain. He may have taken his seat in the senate by the reign of Claudius.[3] In the time of Nero, he may have commanded a legion under the general Gnaeus Domitius Corbulo; during the First Jewish–Roman War, from AD 67 to 68, he came into favour with the future emperor Vespasian, then governor of Judaea, under whom he commanded the Tenth Legion. After his accession to the Empire, Vespasian recognized Traianus' military successes by awarding him the governorship of Cappadocia, and naming him consul suffectus for the months of September and October in AD 72.[a] After his consulship, Trajan served as governor of Syria from AD 73 to 74, then proconsul of Asia from AD 79 to 80. He was also governor of Hispania Baetica, but the time of this appointment is unknown.[6]

Legacy

[edit]

Traianus lived out his final years in honor and distinction. Indirect evidence suggests that he may have died before his son became emperor in AD 98.[7] In AD 100, his son founded a colony in North Africa, named Colonia Marciana Ulpia Trajana Thamugadi after his mother and father; today the town is known as Timgad, in Algeria.[8] In AD 112, Traianus was deified by his son, becoming known as Divus Traianus Pater.[9]

Nerva–Antonine family tree

[edit]

| |

| Notes:

Except where otherwise noted, the notes below indicate that an individual's parentage is as shown in the above family tree.

| |

References:

|

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Gallivan dated Trajan's consulship to AD 70, based on his arrangement of the fragments of tablet 'E' of the Fasti Ostienses;[4] however, subsequent recovery of fragments allowed Vidman to date his tenure to the months of September and October of AD 72.[5]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Ratkovic, Deana (2015). "New Attribution of a Roman Bronze Portrait from Pontes (Iron Gate Limes)". New Research on Ancient Bronzes. 10: 113–116.

- ^ a b c d e Strobel 2010, p. 40.

- ^ a b c d Strobel 2010, p. 41.

- ^ Gallivan 1981, p. 187.

- ^ Vidman, Ladislav (1982). Fasti Ostienses (in Latin). Prague: Academia. pp. 73–75. OCLC 220156633.

- ^ Eck, Werner (1982). "Jahres- und Provinzialfasten der senatorischen Statthalter von 69/70 bis 138/139". Chiron: Mitteilungen der Kommission für Alte Geschichte und Epigraphik des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts (12): 281–362. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ Bennett 1997, p. 20.

- ^ Hitchner, R. Bruce (2022). A Companion to North Africa in Antiquity. John Wiley & Sons. p. 183. ISBN 978-1-4443-5001-2.

- ^ Boatwright, Mary T. (2021). Hadrian and the City of Rome. Princeton University Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-691-22402-2.

Works cited

[edit]- Bennett, Julian (1997). Trajan: Optimus Princeps : a Life and Times. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-16524-2. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- Gallivan, Paul (1981). "The Fasti for A.D. 70–96*". The Classical Quarterly. 31 (1): 186–220. doi:10.1017/S0009838800021194. ISSN 1471-6844. S2CID 171027163. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- Strobel, Karl (2010). Kaiser Traian: eine Epoche der Weltgeschichte (in German). Friedrich Pustet. ISBN 978-3-7917-2172-9. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

General sources

[edit]- "Roman Emperors - DIR Trajan". Roman Emperors. Retrieved 26 March 2020.