Monera: Difference between revisions

| Line 45: | Line 45: | ||

* die Lepomoneren (with envelope): ''Lepomonera'' |

* die Lepomoneren (with envelope): ''Lepomonera'' |

||

** ''Protomonas'' — identified to a synonym of [[Monas (genus)|Monas]], a flagellated protozoan, and not a bacterium.<ref name=Pascoe/> The name was reused in 1984 for an unrelated genus of bacteria.<ref>{{lpsn|p/protomonas|Protomonas}}</ref> |

** ''Protomonas'' — identified to a synonym of [[Monas (genus)|Monas]], a flagellated protozoan, and not a bacterium.<ref name=Pascoe/> The name was reused in 1984 for an unrelated genus of bacteria.<ref>{{lpsn|p/protomonas|Protomonas}}</ref> |

||

** ''[[Vampyrella]]'' — now classed as a eukaryote and not a bacterium. |

** ''[[Vampyrella]]'' — now classed as a eukaryote and not a bacterium.JEREMY BIN TONGOS BIN ANGS BIN ASU JUANCOK |

||

===Subsequent classifications=== |

===Subsequent classifications=== |

||

Revision as of 05:36, 18 April 2012

| Monera Temporal range: Hadean – Recent

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Scanning electron micrograph of Escherichia coli | |

| Scientific classification (obsolete)

| |

| Groups | |

|

According to Haeckel 1866: | |

| Groups included | |

| Cladistically included but traditionally excluded taxa | |

|

Domain Eukaryotes |

Monera (/məˈnɪərə/ mə-NEER-ə) is a kingdom that contains unicellular organisms without a nucleus (i.e., a prokaryotic cell organization), such as bacteria. The kingdom is considered superseded.[1]

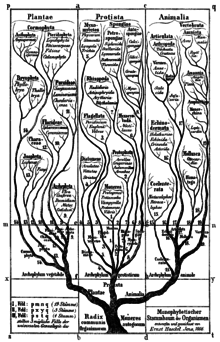

The taxon Monera was first proposed as a phylum by Ernst Haeckel in 1866; subsequently, the taxon was raised to the rank of kingdom in 1925 by Édouard Chatton, gaining common acceptance, and the last commonly accepted mega-classification with the taxon Monera was the five-kingdom classification system established by Robert Whittaker in 1969. Under the three-domain system of taxonomy, which was established in 1990 and reflects the evolutionary history of life as currently understood, the organisms found in kingdom Monera have been divided into two domains, Archaea and Bacteria (with Eukarya as the third domain). Furthermore the taxon Monera is paraphyletic. The term "moneran" is the informal name of members of this group and is still sometimes used (as is the term "prokaryote") to denote a member of either domain.[2]

Despite most bacteria were classified under Monera, the bacterial phylum Cyanobacteria (the blue-green algae) was not initially classified under Monera, but under Plantae given the ability of its members to photosynthesise.

History

Haeckel's classification

Traditionally the natural world was classified as animal, vegetable, or mineral as in Systema Naturae. After the discovery of microscopy, attempts were made to fit microscopic organisms into either the plant or animal kingdoms. In 1676, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek discovered bacteria and called them "animalcules," assigning them to the class Vermes of the Animalia.[4][5][6] Due to the limited tools — the sole references for this group were shape, behaviour, and habitat — the description of genera and their classification was extremely limited, which was accentuated by the perceived lack of importance of the group.[7][8][9]

Ten years after The Origin of Species by Darwin, in 1866 Ernst Haeckel, a supporter of evolution, proposed a three-kingdom system which added the Protista as a new kingdom that contained most microscopic organisms.[3] One of his eight major divisions of Protista was composed of the monerans (called Moneres in German) and defines them as completely structureless and homogeneous organisms, consisting only of a piece of plasma. Haeckel's Monera included not only bacterial groups of early discovery but also several small eukaryotic organisms; in fact the genus Vibrio is the only bacterial genus explicitly assigned to the phylum, while others are mentioned indirectly, which has led Copeland to speculate that Haeckel considered all bacteria to belong to the genus Vibrio, ignoring other bacterial genera.[7] One notable exception were the members of the modern phylum Cyanobacteria, such as Nostoc, which were placed in the phylum Archephyta of Algae (vide infra: Blue-green algae).

The Neolatin noun Monera and the German noun Moneren/Moneres are derived from the ancient Greek noun moneres (μονήρης) which Haeckel states to mean "simple",[3] however it actually means "single, solitary".[10] Haeckel also describes the protist genus Monas in the two pages about Monera in his 1866 book.[3] The informal name of a member of the Monera was initially moneron,[11] but later moneran was used.[2]

Due to its lack of features, the phylum was not fully subdivided, but the genera therein were divided into two groups:

- die Gymnomoneren (no envelope [sic.]): Gymnomonera

- Protogenes — such as Protogenes primordialis, an unidentified amaeba (eukaryote) and not a bacterium

- Protamaeba — an incorrectly described/fabricated species

- Vibrio — a genus of comma-shaped bacteria first described in 1854[12]

- Bacterium — a genus of rod-shaped bacteria first described in 1828. Haeckel does not explicitly assign this genus to the Monera.

- Bacillus — a genus of spore-forming rod-shaped bacteria first described in 1835[13] Haeckel does not explicitly assign this genus to the Monera.

- Spirochaeta — thin spiral-shaped bacteria first described in 1835 [14] Haeckel does not explicitly assign this genus to the Monera.

- Spirillum — spiral-shaped bacteria first described in 1832[15] Haeckel does not explicitly assign this genus to the Monera.

- etc.: Haeckel does provide a comprehensive list.

- die Lepomoneren (with envelope): Lepomonera

- Protomonas — identified to a synonym of Monas, a flagellated protozoan, and not a bacterium.[11] The name was reused in 1984 for an unrelated genus of bacteria.[16]

- Vampyrella — now classed as a eukaryote and not a bacterium.JEREMY BIN TONGOS BIN ANGS BIN ASU JUANCOK

Subsequent classifications

Like Protista, the Monera classification was not fully followed at first and several different ranks were used and located with animals, plants, protists or fungi. Furthermore, Häkel's classification lacked specificity and was not exhaustive —it in fact covers only a few pages—, consequently a lot of confusion arose even to the point that the Monera did not contain bacterial genera and others according to Huxley.[11] The most popular scheme was created in 1859 by C. Von Nägeli who classified non-phototrophic Bacteria as the class Schizomycetes.[17]

The class Schizomycetes was then emended by Walter Migula (along with the coinage of the genus Pseudomonas in 1894)[18] and others.[19] This term was in dominant use even in 1916 as reported by Robert Earle Buchanan, as it had priority over other terms such as Monera.[20] However, starting with Ferdinand Cohn in 1872 the term bacteria (or in German der Bacterien) became prominently used to informally describe this group of species without a nucleus: Bacterium was in fact a genus created in 1828 by Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg[21] Additionally, Cohn divided the bacteria according to shape namely:

- Spherobacteria for the cocci

- Microbacteria for the short, non-filamentous rods

- Desmobacteria for the longer, filamentous rods and Spirobacteria for the spiral forms.

Successively, Cohn created the Schizophyta of Plants which contained the non-photrophic bacteria in the family Schizomycetes and the phototrophic bacteria (blue green algae/Cyanobacteria) in the Schizophyceae[22] This union of blue green algae and Bacteria was much later followed by Haeckel, who classified the two families in a revised phylum Monera in the Protista.[23]

Rise to prominence

The term Monora, became well established in the 20s and 30s when to rightfully increase the importance of the difference between species with a nucleus and without, In 1925 Édouard Chatton divided all living organisms into two empires Prokaryotes and Eukaryotes: the Kingdom Monera being the sole member of the Prokaryotes empire.[citation needed]

The anthropic importance of the crown group of animals, plants and fungi was hard to depose consequently several other megaclassification schemes ignored on the empire rank, but maintained the kingdom Monera consisting of bacteria, such Copeland in 1938 and Whittaker in 1969.[7][24] The latter classification system was widely followed and in which Robert Whittaker proposed a five kingdom system for classification of living organisms.[24] Whittaker's system placed most single celled organisms into either the prokaryotic Monera or the eukaryotic Protista. The other three kingdoms in his system were the eukaryotic Fungi, Animalia, and Plantae. Whittaker, however, did not believe that all his kingdoms were monophyletic.[25] Whittaker subdiveded the kingdom into two branches containing several phyla:

- Myxomonera branch

- Cyanophyta, now called Cyanobacteria

- Myxobacteria

- Mastigomonera branch

Alternative commonly followed subdivision systems were based on Gram stains. This culminated in the Gibbons and Murray classification of 1978:[26]

- Gracilicutes (gram negative)

- Photobacteria (photosynthetic): class Oxyphotobacteriae (water as electron acceptor, includes the order Cyanobacteriales=blue green algae, now phylum Cyanobacteria) and class Anoxyphotobacteriae (anaerobic phototrophs, orders: Rhodospirillales and Chlorobiales

- Scotobacteria (non-photosynthetic, now the Proteobacteria and other gram negative nonphotosynthetic phyla)

- Firmacutes [sic] (gram positive, subsequently corrected to Firmicutes[27])

- several orders such as Bacillales and Actinomycetales (now in the phylum Actinobacteria)

- Mollicutes (gram variable, e.g. Mycoplasma)

- Mendocutes (uneven gram stain, "methanogenic bacteria" now known as the Archaea)

Three-domain system

In 1977, a PNAS paper by Carl Woese and George Fox demonstrated that the archaea (initially called archaebacteria) are not significantly closer in relationship to the bacteria than they are to eukaryotes. The paper received front-page coverage in The New York Times [28], and great controversy initially. The conclusions have since become accepted, leading to replacement of the kingdom Monera with the two kingdoms Bacteria and Archaea.[25][29] However, Thomas Cavalier-Smith has never accepted the importance of the division between these two groups, and has published classifications in which the archaebacteria are part of a subkingdom of the Kingdom Bacteria.[30]

Blue-green algae

Although it was generally accepted that one could distinguish prokaryotes from eukaryotes on the basis of the presence of a nucleus, mitosis versus binary fission as a way of reproducing, size, and other traits, the monophyly of the kingdom Monera (or for that matter, whether classification should be according to phylogeny) was controversial for many decades. Although distinguishing between prokaryotes from eukaryotes as a fundamental distinction is often credited to a 1937 paper by Édouard Chatton (little noted until 1962), he did not emphasize this distinction more than other biologists of his era.[25] Roger Stanier and C. B. van Niel believed that the bacteria (a term which at the time did not include blue-green algae) and the blue-green algae had a single origin, a conviction which culminated in Stanier writing in a letter in 1970, "I think it is now quite evident that the blue-green algae are not distinguishable from bacteria by any fundamental feature of their cellular organization".[31] Other researchers, such as E. G. Pringsheim writing in 1949, suspected separate origins for bacteria and blue-green algae. In 1974, the influential Bergey's Manual published a new edition coining the term cyanobacteria to refer to what had been called blue-green algae, marking the acceptance of this group within the Monera.[25]

Summary

| Linnaeus 1735[32] |

Haeckel 1866[3] |

Chatton 1925[33] |

Copeland 1938[7] |

Whittaker 1969[24] |

Woese et al. 1990[34] |

Cavalier-Smith 1998,[30] 2015[35] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 kingdoms | 3 kingdoms | 2 empires | 4 kingdoms | 5 kingdoms | 3 domains | 2 empires, 6/7 kingdoms |

| (not treated) | Protista | Prokaryota | Monera | Monera | Bacteria | Bacteria |

| Archaea | Archaea (2015) | |||||

| Eukaryota | Protoctista | Protista | Eucarya | "Protozoa" | ||

| "Chromista" | ||||||

| Vegetabilia | Plantae | Plantae | Plantae | Plantae | ||

| Fungi | Fungi | |||||

| Animalia | Animalia | Animalia | Animalia | Animalia |

See also

References

- ^ George M. Garrity, ed. (July 26, 2005) [1984(Williams & Wilkins)]. Introductory Essays. Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. Vol. 2A (2nd ed.). New York: Springer. p. 304. ISBN 978-0-387-24143-2. British Library no. GBA561951.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Moneran", Encyclopædia Britannica Online, 2011, retrieved 2011-08-09

- ^ a b c d e Ernst Heinrich Philipp August Haeckel (1867). Generelle Morphologie der Organismen. Reimer, Berlin. ISBN 1144001862. Cite error: The named reference "Haeckel" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ van Leeuwenhoek A (1684). "An abstract of a letter from Mr. Anthony Leevvenhoek at Delft, dated Sep. 17, 1683, Containing Some Microscopical Observations, about Animals in the Scurf of the Teeth, the Substance Call'd Worms in the Nose, the Cuticula Consisting of Scales". Philosophical Transactions (1683–1775). 14 (155–166): 568–574. doi:10.1098/rstl.1684.0030. Retrieved 2007-08-19.

- ^ van Leeuwenhoek A (1700). "Part of a Letter from Mr Antony van Leeuwenhoek, concerning the Worms in Sheeps Livers, Gnats, and Animalcula in the Excrements of Frogs". Philosophical Transactions (1683–1775). 22 (260–276): 509–518. doi:10.1098/rstl.1700.0013. Retrieved 2007-08-19.

- ^ van Leeuwenhoek A (1702). "Part of a Letter from Mr Antony van Leeuwenhoek, F. R. S. concerning Green Weeds Growing in Water, and Some Animalcula Found about Them". Philosophical Transactions (1683–1775). 23 (277–288): 1304–11. doi:10.1098/rstl.1702.0042. Retrieved 2007-08-19.

- ^ a b c d Copeland, H. (1938). "The kingdoms of organisms". Quarterly Review of Biology. 13 (4): 383–420. doi:10.1086/394568. S2CID 84634277.

- ^ George M. Garrity, ed. (July 26, 2005) [1984(Williams & Wilkins)]. Introductory Essays. Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. Vol. 2A (2nd ed.). New York: Springer. p. 304. ISBN 978-0-387-24143-2. British Library no. GBA561951.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 2439888, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=2439888instead. - ^ monh/rhs. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

- ^ a b c {{cite book|url=http://www.archive.org/details/zoologicalclassi00pasc%7Cauthor=Francis Polkinghorne Pascoe|year=1880|name=Zoological classification; a handy book of reference with tables of the subkingdoms, classes, orders, etc., of the animal kingdom, their characters and lists of the families and principal genera

- ^ PACINI (F.): Osservazione microscopiche e deduzioni patologiche sul cholera asiatico. Gazette Medicale de Italiana Toscano Firenze, 1854, 6, 405-412.

- ^ EHRENBERG (C.G.): Dritter Beitrag zur Erkenntniss grosser Organisation in der Richtung des kleinsten Raumes. Physikalische Abhandlungen der Koeniglichen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin aus den Jahren 1833-1835, 1835, pp. 143-336.

- ^ EHRENBERG (C.G.): Dritter Beitrag zur Erkenntniss grosser Organisation in der Richtung des kleinsten Raumes. Abhandlungen der Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften (Berlin) aus den Jahre 1833-1835, pp. 143-336.

- ^ EHRENBERG (C.G.): Beiträge zur Kenntnis der Organization der Infusorien und ihrer geographischen Verbreitung besonders in Sibirien. Abhandlungen der Koniglichen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin, 1832, 1830, 1-88.

- ^ Protomonas in LPSN; Parte, Aidan C.; Sardà Carbasse, Joaquim; Meier-Kolthoff, Jan P.; Reimer, Lorenz C.; Göker, Markus (1 November 2020). "List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN) moves to the DSMZ". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 70 (11): 5607–5612. doi:10.1099/ijsem.0.004332.

- ^ C. Von Nägeli (1857). R. Caspary (ed.). "Bericht über die Verhandlungen der 33. Versammlung deutscher Naturforscher und Aerzte, gehalten in Bonn von 18 bis 24 September 1857". Botanische Zeitung. 15: 749–776.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Migula, W. (1894) Über ein neues System der Bakterien. Arb Bakteriol Inst Karlsruhe 1: 235–328.

- ^ CHESTER, F. D. 1897 Classification of the Schizomycetes. Annual Report Delaware College Agricultural Experiment Station, 9, 62.

- ^ Buchanan, R E J Bacteriol. 1916 Nov;1(6):591-6.ISSN 0021-9193 PMCID 378679

- ^ Ferdinand Cohn (1872). "Untersuchungen uber Bakterien". Vol. 1. pp. 127–224 http://books.google.co.nz/books?id=wnyHvEtfRrQC&dq=COHN%2C%20FERDINAND%201872%20.%20Beitr%C3%A4ge%20zur%20Biologie%20der%20Pflanzen&pg=RA1-PA127#v=onepage&q&f=false.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help); Unknown parameter|name=ignored (help) - ^ Ferdinand Cohn (1875). "Untersuchungen uber Bakterien". Vol. 1. pp. 141–208.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help); Unknown parameter|name=ignored (help) - ^ Ernst Haeckel. The Wonders of Life. Translated by Joseph McCabe. New York and London. I904.

- ^ a b c Robert Whittaker (1969). "New concepts of kingdoms or organisms. Evolutionary relations are better represented by new classifications than by the traditional two kingdoms". Science. 163 (3863): 150–160. doi:10.1126/science.163.3863.150. PMID 5762760. Cite error: The named reference "Whittaker1969" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c d Jan Sapp (June 2005). "The Prokaryote-Eukaryote Dichotomy: Meanings and Mythology". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 69 (2): 292–305. doi:10.1128/MMBR.69.2.292-305.2005. PMC 1197417. PMID 15944457.

- ^ GIBBONS (N.E.) and MURRAY (R.G.E.): Proposals concerning the higher taxa of bacteria. International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology, 1978, 28, 1-6.

- ^ MURRAY (R.G.E.): The higher taxa, or, a place for everything...? In: N.R. KRIEG and J.G. HOLT (ed.) Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, vol. 1, The Williams & Wilkins Co., Baltimore, 1984, p. 31-34

- ^ Lyons, Richard D. (Nov 3, 1977). "Scientists Discover a Form of Life That Predates Higher Organisms". The New York Times.

{{cite news}}:|section=ignored (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|day_of_week=(help); Unknown parameter|page_number=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|page_numbers=ignored (help) - ^ Holland L. (22). "Woese,Carl in the forefront of bacterial evolution revolution". scientist. 4 (10).

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=,|date=, and|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ a b Cavalier-Smith, T. (1998). "A revised six-kingdom system of life". Biological Reviews. 73 (3): 203–66. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.1998.tb00030.x. PMID 9809012. S2CID 6557779.

- ^ Roger Stanier to Peter Raven, 5 November 1970, National Archives of Canada, MG 31, accession J35, vol. 6, as quoted in Sapp, 2005

- ^ Linnaeus, C. (1735). Systemae Naturae, sive regna tria naturae, systematics proposita per classes, ordines, genera & species.

- ^ Chatton, É. (1925). "Pansporella perplexa. Réflexions sur la biologie et la phylogénie des protozoaires". Annales des Sciences Naturelles - Zoologie et Biologie Animale. 10-VII: 1–84.

- ^ Woese, C.; Kandler, O.; Wheelis, M. (1990). "Towards a natural system of organisms:proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 87 (12): 4576–9. Bibcode:1990PNAS...87.4576W. doi:10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. PMC 54159. PMID 2112744.

- ^ Ruggiero, Michael A.; Gordon, Dennis P.; Orrell, Thomas M.; Bailly, Nicolas; Bourgoin, Thierry; Brusca, Richard C.; Cavalier-Smith, Thomas; Guiry, Michael D.; Kirk, Paul M.; Thuesen, Erik V. (2015). "A higher level classification of all living organisms". PLOS ONE. 10 (4): e0119248. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1019248R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0119248. PMC 4418965. PMID 25923521.

External links

- Woese CR (1987). "Bacterial evolution". Microbiol. Rev. 51 (2): 221–71. PMC 373105. PMID 2439888.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) Woese reviewed the historical steps leading to the use of the term "Monera" and its later abandonment. - What is Monera? A descriptive details of the entire kingdom