Mongol invasions of Japan

The Mongol invasions of Japan (元寇, Genkō) of 1274 and 1281 were major events of macrohistorical importance, despite their ultimate failures. These invasion attempts are among the most famous events in Japanese history, and due to their role in setting a limit on Mongol expansion, are arguably crucial events to world history as a whole. They are referred to in many works of fiction, and are the earliest events for which the word kamikaze, or "divine wind", is widely used. In addition, with the possible exception of the end of World War II, these failed invasion attempts are the closest Japan has ever come to being invaded within the last 1500 years or so.

The Invasions

Kublai Khan became Emperor of China in 1259 and established his capital at Beijing in 1264. Korea was soon forced to submit to Mongol control. Two years later, he dispatched emissaries to Japan, commanding the Japanese to submit to Mongol rule, or face invasion. A second set of emissaries were sent in 1268, returning empty-handed, like their predecessors. Both sets of emissaries met with the Chinzei Bugyō, or Defense Commissioner for the West, who passed on the message to the Shogun in Kamakura, and the Emperor in Kyoto. A number of messages were sent after that, some through Korean emissaries, and some by Mongol ambassadors. The bakufu (the Shogun's government) ordered all those who held fiefs in Kyushu (the area closest to Korea, and thus most likely to be attacked) to return to their lands, and forces in Kyushu moved west, further securing the most likely landing points. In addition, great prayer services were organized, and much government business was put off to deal with this crisis.

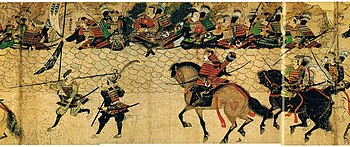

The Khan was willing to go to war as early as 1268, but found that the Koreans did not have the resources to provide him with a sufficient army or navy at that time. He sent a force to Korea in 1273, to act as the advance guard, but they were unable to support themselves off the Korean countryside, and were forced to return to China for supplies. Finally, in 1274, the Mongol fleet set out, with roughly 15,000 Mongol & Chinese soldiers and 8,000 Korean warriors, in 300 large vessels and 400-500 smaller craft. They captured the islands of Tsushima and Iki easily, and landed on November 19th in Hakata Bay, a short distance from Dazaifu, the ancient administrative capital of Kyushu. The following day brought the Battle of Bun'ei (文永の役), also known as the "Battle of Hakata Bay"; the Mongols had superior weapons and tactics, but they were vastly outnumbered by the Japanese warriors who had been preparing for the attack for months, and who had received reinforcements as soon as they learned of the losses of Tsushima and Iki. They held out all day, and a storm that night persuaded the Mongols to retreat.

Starting in 1275, the Bakufu made increased efforts to defend against the second invasion which they thought was sure to come. In addition to better organizing the samurai of Kyushu, they ordered the construction of forts and other defensive structures at many potential landing points, including Hakata. Meanwhile, the king of Korea tried many times to negotiate with the Mongols, arguing against further attempts to invade Japan.

In the spring of 1281, the Mongols' Chinese fleet was delayed by difficulties in provisioning and manning the large number of ships they had. Their Korean fleet set sail, suffered heavy losses at Tsushima, and turned back. In the summer, the combined Korean/Chinese fleet took Iki-shima, and moved on to Kyushu, landing at a number of separate positions. In a number of individual skirmishes, known collectively as the Battle of Kouan (弘安の役), or the Second Battle of Hakata Bay, the Mongol forces were driven back to their ships. The now-famous kamikaze, a massive typhoon, assaulted the shores of Kyushu for two days straight, and destroyed much of the Mongol fleet.

The Aftermath

Kublai Khan desired to try to invade Japan once again in 1286, but he found his resources severely lacking for such an attempt. Back in Japan, the nationwide reorganization needed to repel the Mongols had put the entire economy and military under pressure, and stretched the country's resources to their limits. The attacks also provided the bakufu with an excuse to maintain their command of the country, rather than turning control over to the Emperor. They continued for several years to reinforce the defenses of Kyushu, and many military measures remained in force there for many years.

Though it is not universally agreed upon, many scholars today believe that the numbers of warriors on both sides in the invasions were much lower than traditionally stated. Many scholars also assert that the Japanese were capable of effectively repelling the invaders even without the fortuitous and famous kamikaze.

Resources

- Sansom, George (1958). 'A History of Japan to 1334'. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.