Pains and Penalties Bill 1820

The Pains and Penalties Bill 1820 was a bill introduced to the British Parliament in 1820, at the request of King George IV, which aimed to dissolve his marriage to Caroline of Brunswick, and deprive her of the title of Queen of Great Britain and Ireland.

George and Caroline had married in 1795, when George was still Prince of Wales. After the birth of their only child, Princess Charlotte of Wales, they separated. Caroline eventually went to live abroad, where she appointed Bartolomeo Pergami to her household as a courier. He eventually rose to become the head servant of her household, and it was widely rumoured that they were lovers.

In 1820, George ascended the throne and Caroline travelled to London to assert her rights as queen consort of Great Britain and Ireland. George despised her and was adamant that he wanted a divorce. Under English law, however, divorce was not then possible unless one of the parties was guilty of adultery. As neither he nor Caroline would admit to adultery, George had a bill introduced to Parliament, which if passed would declare Caroline to have committed adultery and grant the King a divorce. In essence, the reading of the bill was a public trial of the Queen, with the members of the House of Lords and the House of Commons acting as judge and jury.

After a sensational debate in the Lords, which was heavily reported in the press in salacious detail, the bill was narrowly passed by the upper house. However, because the margin was so slim and public unrest over the bill was significant, the government withdrew the bill before it was debated by the House of Commons, as the likelihood of it ever passing there was remote.

Background

In 1795, George, Prince of Wales, the eldest son of King George III, married Duchess Caroline of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel. The marriage, however, was disastrous; each party was unsuited to the other. They separated after the birth of their only child, Princess Charlotte of Wales, the following year. Caroline was soon banished from court,[citation needed] and eventually departed England for the European mainland. On the death of George III on 29 January 1820, George became king as George IV, and Caroline became queen consort. However, George IV refused to recognise Caroline as queen and commanded British ambassadors to ensure that monarchs in foreign courts did the same. Her name was omitted from the liturgy of the Church of England, and George acted to exclude her at every opportunity. In June, Caroline returned to London to assert her rights as queen consort of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

George despised her, and over the preceding few years had collected evidence to support his contention that Caroline had committed adultery while abroad with Bartolomeo Pergami, the head servant of her household. The day after her return to England, George submitted the evidence to the Houses of Parliament in two green bags. The contents of the bags were identical; one copy was presented to the House of Lords by the Prime Minister, Lord Liverpool, and the other was presented to the House of Commons by the Foreign Secretary, Lord Castlereagh. Each requested that the Houses set up a confidential enquiry to examine the contents of the bags.[2] Replying to Castlereagh in the Commons, Caroline's chief attorney, Henry Brougham,[3] demanded that the papers be publicly disclosed. Brougham was in the opposition Whig party and knew that public sympathy rested with Caroline, rather than her husband or the government, which was weak and unpopular. Disclosure of George's own adulterous affairs, or even his scandalous and unlawful previous marriage to Maria Fitzherbert, could destabilise the Tory government led by Lord Liverpool.[4]

In an attempt to construct a compromise, Castlereagh and the Duke of Wellington met Brougham and Caroline's solicitor Thomas Denman. William Wilberforce secured time for negotiation by persuading the Commons to adjourn the debate on the bags. However, the negotiations were fruitless; the government offered Caroline £50,000 a year to live abroad as a Duchess, but Caroline insisted on her right to be Queen and dismissed the money as a bribe.[5] Wilberforce moved a motion in the House of Commons requesting that Caroline not insist on all her claims, which was passed by a wide margin of 394 votes to 124. However, the public was still solidly behind Caroline, and she rejected Wilberforce's request.[6] George Canning, who may have been a former lover of Caroline, threatened to resign from the government in protest at the proceedings against her. If Canning resigned, the government would almost certainly fall. In the end, either he was persuaded not to resign or his resignation was refused. His eldest son had recently died and, rather than be involved in the debate, Canning left Britain on a tour of Europe to recover from his grief.[7]

On 27 June, the Lords rejected a motion made by the Whig leader Lord Grey to abandon the investigation, and the bags were opened and examined by a committee of fifteen peers.[8] A week later, the chair of the committee, Lord Harrowby, reported back to the Lords. The committee decided that the evidence was of such a grave and serious nature that it should be the subject of a "legislative proceeding".[9] In reply, Lord Liverpool announced that a bill would be introduced the following day.

Bill

On 5 July, a bill was introduced into Parliament "to deprive Her Majesty Queen Caroline Amelia Elizabeth of the Title, Prerogatives, Rights, Privileges, and Exemptions of Queen Consort of this Realm; and to dissolve the Marriage between His Majesty and the said Caroline Amelia Elizabeth." The bill charged that Caroline had committed adultery with Bartolomeo Pergami, "a foreigner of low station", and that consequently she had forfeited her rights to be queen consort.[11]

The debate on the bill was effectively a public trial of the Queen, during which the government could call witnesses against her who could be cross-examined by her own legal advisors. By voting on the bill, members of the Houses of Parliament would be both jury and judges. Caroline would not receive basic rights accorded to other defendants; for example, she would not be informed of who the witnesses were before they were called. It was, said the Times newspaper, "a violation of the law of God".[12] The British people seemed to be on Caroline's side and gave her strong support.

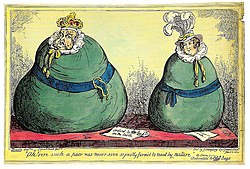

George lived a hugely extravagant life on the taxes collected by Parliament, whereas Caroline appeared to live modestly.[13] Satirists and cartoonists published prints in support of Caroline and depicted George as debauched and licentious.[14] She received messages of support from all over the country. Caroline was a figurehead for the growing radical movement that demanded political reform and opposed the unpopular George.[15] By August, Caroline had allied with radical campaigners such as William Cobbett, and it was probably Cobbett who wrote these words of Caroline's:[16]

If the highest subject in the realm can be deprived of her rank and title—can be divorced, dethroned and debased by an act of arbitrary power, in the form of a Bill of Pains and Penalties—the constitutional liberty of the Kingdom will be shaken to its very base; the rights of the nation will be only a scattered wreck; and this once free people, like the meanest of slaves, must submit to the lash of an insolent domination.[17]

The day before the trial was due to start an open letter from Caroline to George, again probably written by Cobbett, was published widely. In it, she decried the injustices against her, claimed she was the victim of conspiracy and intrigue, accused George of heartlessness and cruelty, and demanded a fair trial.[18] The letter was seen as a challenge, not only to George but to the government and the forces resisting reform.[19]

Trial

On 17 August 1820, the trial opened. Amid a large military presence, crowds gathered to watch the peers and the Queen attend Parliament.[20] Once in their chamber, the Lords began the bill's second reading (the first reading was a formality). Lord Chancellor Lord Eldon, acting as the Speaker of the House, noted the absence of several peers, notably Lords Byron and Erskine, because they were either abroad or too elderly to attend. Caroline's brother-in-law, Prince Augustus, Duke of Sussex, asked to be excused from participating on the grounds of consanguinity. His request was granted, though his brother, Prince Frederick, Duke of York, announced that he would continue to attend.[21]

The first motion was moved by the Duke of Leinster, to the effect that the bill be dismissed. It was an initial test of the government's strength that would gauge support for the King. The motion was lost by 206–41.[22] During the first day and the next, opening speeches by Caroline's defence team, Henry Brougham and Thomas Denman, were well received.[23] In their speeches, Brougham and Denman hinted but did not state explicitly, referring only to "recrimination", that George could come off worse because of the bill if his own infidelities (such as his secret marriage to Maria Fitzherbert) were revealed in the course of the debate.[23] In private, the Queen also turned the tables on the King by saying, "[I] never committed adultery but once, and that was with Mrs Fitzherbert's husband."[24]

The prosecution case, led by the Attorney General for England and Wales Sir Robert Gifford, began on Saturday 19 August. The Queen did not attend. Gifford claimed that Caroline and Pergami had lived as lovers for five years from November 1814. He asserted that they shared a bedroom, were seen in each other's presence arm-in-arm, and were heard kissing. The Queen, he stated, changed clothes in front of Pergami and ate her meals with him. He said that Pergami was a married man, but although his child, sister, mother and brother lived in the Queen's household, his wife did not.[25] The Sunday newspapers the following morning were filled with the salacious details of Gifford's speech.[26] Gifford resumed his attack on Monday 21 August by recounting further outrageous revelations: Pergami and Caroline had been seen together on a bed in a state of undress; she had sat on Pergami's knee in public; she had taken baths accompanied only by Pergami.[27] High society did not receive the speech well. They were appalled at Caroline's behaviour, but they were more appalled at George's. By forcing the details of Caroline's life into the public arena, George had damaged the monarchy and endangered the political status quo.[28] Leigh Hunt wrote to Percy Bysshe Shelley, "The whole thing will be one of the greatest pushes given to the declining royalty that the age has seen."[29]

The first witness for the prosecution was an Italian servant, Theodore Majocchi. The prosecution's reliance on Italian witnesses of low birth led to anti-Italian prejudice in Britain. The witnesses had to be protected from angry mobs,[30] and were depicted in popular prints and pamphlets as venal, corrupt and criminal.[31] Street-sellers sold prints alleging that the Italians had accepted bribes to commit perjury.[32] After Gifford's speech on 21 August, Caroline entered the chamber of the House of Lords. Shortly afterwards, Majocchi was called. As he was led in, Caroline rose and advanced towards him, flinging back her veil. She apparently recognised him, exclaimed "Theodore!", and rushed out of the House.[33] Her sudden sensational departure was seen as a "burst of agony" by The Times,[34] but others thought it the mark of a guilty conscience.[35] It led her defence team to advise her against attending in future, unless specifically requested.[36] Indeed, the evidence was so demeaning that the Queen did usually absent herself from the chamber, though she went to the House of Lords.[37] According to Princess Lieven, Caroline passed the time by playing backgammon in a side-room.[38]

Prosecution case

Under examination by the Solicitor General for England and Wales, John Singleton Copley, Majocchi testified that Caroline and Pergami ate breakfast together, had adjoining bedrooms, and had kissed each other on the lips. He said Pergami's bed was not always slept in, and he had seen Pergami visit the Queen wearing only underwear and a dressing gown.[39] He said that they had slept in the same tent during a trip around the Mediterranean, and that Pergami had attended the Queen, alone, while she was having a bath.[40] The following day, his astonishing testimony continued with the revelation that when Caroline and Pergami were travelling together in a carriage, Pergami kept a bottle with him so he could relieve himself without having to step down from the coach.[41] The situation in the House became more absurd, as the Solicitor General asked Majocchi about a male exotic dancer employed by Caroline, after which Majocchi demonstrated a dance by pulling up his trousers, extending his arms, clicking his fingers, and shouting "vima dima!", while moving his body up and down in a suggestive fashion.[42] The Times newspaper was disgusted and informed its readers that it regretted being "obliged" to report "filth of this kind".[34] During Brougham's cross-examination, Majocchi replied "Non mi ricordo (I don't recall)" more than two hundred times. The phrase was repeated so often, it became a national joke, and featured in cartoons and parodies.[43] Majocchi's credibility as a witness was destroyed.[44]

The next witness was ship's mate Gaetano Paturzo, who claimed that he had seen Caroline sitting on Pergami's lap, but nothing more, while on a Mediterranean cruise. Ship's master Vincenzo Garguilo testified that Caroline and Pergami had shared a tent on deck and had kissed. Under cross-examination, he admitted that he had been paid to give evidence, but said that the payment was lower in value than the business he had lost through coming to England.[45] Captain Thomas Briggs of HMS Leviathan, another vessel used by Caroline and Pergami during their journey, was also called as a prosecution witness. He said that the two had adjoining cabins on board and he had seen them arm-in-arm. Unlike the Italian witnesses, as an Englishman of some substance, the Lords considered Captain Briggs to be a more credible witness.[46] After the conclusion of the cross-examination, however, Lord Ellenborough rose and asked Briggs directly, "Did the witness see any improper familiarity between the Princess and Pergami? Had you any reason to suspect any improper freedom or familiarity between them?" "No", replied Briggs.[45]

A further witness, Pietro Cuchi, an innkeeper in Trieste, told the Lords that he had spied on the couple through a keyhole, during which he thought he saw Pergami leave the Queen's bedroom wearing stockings, pantaloons and a dressing gown. However, he couldn't be sure because his view, through the keyhole, was restricted. He did say that Pergami's bed was not slept in, and that both chamber pots in Caroline's room were used.[47]

As Princess Lieven observed, the trial was a "solemn farce".[48] On 25 August, a chambermaid from Karlsruhe, Barbara Kress, was sworn in. She was asked about the sheets on the Queen's bed: "Did you at any time see anything on the sheets?", asked the Attorney General. Her response was quietly spoken. Two interpreters, one for the King and one for the Queen, formed a huddle around the witness. The Queen's interpreter claimed the response wuste was not translatable; the King's interpreter was asked to press the witness for a further explanation. The witness broke down, and the proceedings were paused to allow her to regain composure. An eventual translation of "stains" was agreed.[49] Tory Harriet Arbuthnot wrote in her journal "if the Whig Lords do not consider the disgusting details they have heard proof, the Whig ladies may in future consider themselves very secure against divorces."[50]

Caroline's former maid, Louise Demont, testified she had seen Caroline leave Pergami's bedroom wearing only a nightdress, and corroborated previous evidence that Caroline and Pergami had shared a tent and a bath during the cruise.[51] She was also asked about stains on the bed-sheets, but refused to be drawn into details because it was "not decent".[52] Under cross-examination, she was accused of living in England for more than a year under the assumed name of "Countess Colombier". Demont's flustered reply mimicked those of Majocchi, as she claimed she could not recall being called by that name.[53] The defence said she had been sacked for lying, and produced a letter written by Demont in which she admitted coming to England on a "false pretence".[53] Demont's sister, Mariette Brun, had remained in Caroline's service as a maid, and had passed information on her sister to Caroline's defence team.[53]

The procession of witnesses continued; a mason Luigi Galdini claimed he had stumbled across Pergami holding Caroline's bare breast in their Italian villa.[37] Coachman Giuseppe Sacchi, who was Demont's lover,[54] claimed that he had found the couple asleep in a carriage in each other's arms, with Caroline's hand on Pergami's undone breeches.[55] Sacchi's testimony was ridiculed in the British press, as "the parties being asleep, such a position in a carriage, where the bodies are themselves upright, or nearly so, is beyond all question absolutely and physically impossible."[56]

Defence case

In a letter to the King, the Prime Minister Lord Liverpool summarised the progress of the trial. He said the evidence had made an impression in the House, but the bill was by no means secure.[57] The Queen was still immensely popular. Over 800 petitions totalling nearly a million signatures were received in her favour.[58] Liverpool warned the King that Majocchi and Demont were discredited as witnesses, and the evidence produced by the defence could damage George severely. The divorce clause was especially unpopular, he wrote, though it might pass the Lords, it would not pass the Commons. He suggested that it be dropped. George would not decide to do so.[57]

After the presentation of the prosecution case, the trial was adjourned for three weeks, and the Queen's solicitor, Denman, visited Cheltenham Spa for a break.[59] Once his identity was discovered, a supportive crowd gathered outside his lodgings.[60] Meanwhile, Caroline's defence team assembled their evidence. Letters exchanged between them and Italian correspondents show that Colonel Carlo Vassalli, Caroline's equerry, said there was nothing improper between Caroline and Pergami. Caroline shared a room with Victorine, Pergami's daughter, and Caroline's behaviour with Pergami was no different than with other men.[61] Pergami himself wrote from Pesaro in Italy that he would swear that his bed was not slept in because he was sleeping with Demont, and that he never had intercourse with the Queen.[62]

The defence opened on 3 October, with a speech from Brougham. His speech was considered the "most magnificent display of argument and oratory that has been heard in years",[63] "one of the most powerful orations that ever proceeded from human lips",[64] and "one of the most magnificent speeches ever made in this or any other country".[65] According to Thomas Creevey, it astonished and shook the aristocracy.[66] In it, Brougham threatened to reveal facts about George's own life, even if they damaged the country, if it was the only way to ensure justice for his client.[67] He attacked the character of the prosecution witnesses, and claimed that Italian witnesses could be purchased like a commodity. He read from a letter from an Italian correspondent, "There is nothing at Naples so notorious as the free and public sale of false evidence. Their ordinary tariff is three or four ducats."[68] He reminded the Lords that Majocchi was forgetful, that Demont was a liar, and that Cuchi was a lecherous wretch who spied on his female guests through a keyhole.[69] He produced a letter from George to Caroline written in 1796, which became known as the "letter of licence". It appeared to forgive any transgressions on either Caroline or his part, and allow them to lead separate lives. "Our inclinations are not in our power," George had written, "nor should either of us be held accountable to the other."[70]

The defence witnesses included Lord Guilford, Lord Glenbervie, Lady Charlotte Lindsay, Lord Landaff, The Hon. Keppel Craven, Sir William Gell, Dr Henry Holland, Colonel Alessandro Olivieri, and Carlo Vassalli, all of whom swore that there was nothing unusual about Caroline's behaviour.[71] The King was incensed; "I never thought that I should have lived to witness so much prevarication, so much lying, and so much wilful and convenient forgetfulness", he wrote.[72] Under cross-examination, Lord Guilford was unable to recall leaving a handsome Greek servant alone with Caroline for three-quarters of an hour,[73] and Lady Charlotte had on occasion said "I do not recollect", but without the same disdain that had met Majocchi's constant refrain of non mi ricordo.[74] British servants who had been in Caroline's household, including Keppel's valet John Whitcomb, also testified in Caroline's favour. Whitcomb admitted that he had slept with Demont, who was already known to have slept with the coachman Sacchi, thus further ruining Demont's tarnished reputation.[75] A French milliner, Fanchette Martigner, further testified that Demont had told her that Caroline was innocent, and the charges against her "were nothing but calumnies invented by her enemies in order to ruin her".[76]

The trial seemed to be going Caroline's way, especially after Sacchi's testimony was refuted by the nephew of the Duchess of Torlonia, Carlo Forti. Forti claimed that the Countess Oldi (Pergami's sister) sat between Caroline and Pergami in the carriage, which was also shared with Victorine (Pergami's daughter), and so there could have been no intimacy between them.[77] However, the cross-examination of two of the witnesses damaged Caroline's case. Lieutenant John Flynn and Joseph Hownam had both been on the same Mediterranean cruise with Caroline and Pergami. Flynn said nothing incriminating but during the course of the cross-examination, he fainted, which left a bad impression.[78] Pressed by Gifford, Hownam admitted that Caroline and Pergami had both slept in the same tent on deck because, he claimed, Caroline was afraid of pirates, and wanted a guard in the tent with her.[79] In an attempt to regain ground, Brougham produced two Italian witnesses, Giuseppe Giroline and Filippo Pomi, who revealed that the prosecution witnesses had been paid 40 francs each, and given free food and board.[80] The Whigs now claimed that the trial was tainted as there was prima facie evidence of conspiracy to pervert the course of justice by paying witnesses for their testimony.[81] Lord Liverpool countered Whig demands to abandon the bill by saying that there was other evidence, from non-Italian witnesses, that could be relied upon.[81]

Brougham attempted to investigate the claim of conspiracy further in the hope that it would discover the man behind the conspiracy, who paid for the witnesses and hired the prosecution team. Disingenuously referring to "this mysterious being, this retiring phantom, this uncertain shape", Brougham knew full well that "this uncertain shape" was the King. The King knew it too, and took Brougham's words to be a direct reference to his massive size, as the King was vastly overweight.[82] The Tories challenged Brougham's line of questioning, as they claimed it implicated persons who could not be called as witnesses, and widened the investigation beyond the relevance of the bill.[83]

Passed but withdrawn

For ten hours over two days, Thomas Denman summed up for the defence. He cited the dishonesty of the principal prosecution witnesses, the evidence of the defence witnesses that contradicted that of the prosecution, and drew parallels between George and the Roman emperor Nero. He said Nero had banished his wife, Claudia Octavia, and taken a mistress in her place. He'd then concocted a conspiracy to dethrone, degrade and divorce her, before she was ultimately condemned and killed.[84] A second member of the defence team, Stephen Lushington, then spoke for a shorter time to highlight the main points of the defence case.[85] In concluding the prosecution, Gifford reiterated the claims of Demont and Majocchi, and claimed that they were "undeniable proof of her Majesty's guilt".[86]

The Lords proceeded to debate the bill. The Whig leader Lord Grey complained that the bill was far removed from ordinary legal practice, and pointed out that, if the Lords passed the bill, the entire process would have to be repeated in the Commons, leading to more public strife. Furthermore, the evidence was insufficient, tainted or contradicted. Even if Caroline had shown Pergami favour, it was within the power of royalty to elevate anyone from a low rank to a high one, and it was a strength of society that any person could rise from the lowest of births to the highest of offices. Indeed, Caroline and Pergami had lived at Naples, where the King himself (Joachim Murat) had risen from humble origins. They had travelled through countries that through the influence of the French revolution had seen the reversal of traditional power structures, with the once-wealthy laid low, and the obscure propelled to distinction.[87]

The vote was held on 6 November 1820, three years to the day since Caroline's only daughter, Princess Charlotte Augusta of Wales, had died. Each peer rose and said either "content", indicating support for the bill, or "not content", to oppose it. The vote was 123–95 in favour.[88] Though the majority was 28, it was considered a narrow victory. Eleven of the votes in favour were from the bishops who sat in the House of Lords, while many of the votes against were from the richest and most powerful peers.[89] As seats in the House of Commons were often controlled by rich and powerful landowners, it meant that the Commons were almost certain to reject the bill. Consequently, over the next few days the Lords debated dropping the divorce clause, but the Whigs had spotted a tactical opportunity. Lord Grey now spoke in favour of retaining the divorce clause, since by doing so it made the bill more likely to fail in the Commons. On 10 November, a final reading of the bill took place, and a further vote was held. The bill passed by 108–99, with a majority of 9.[90]

In a highly emotional state,[91] the Prime Minister Lord Liverpool rose to address the House. He declared that since the vote was so close, and public tensions so high, the government was withdrawing the bill.[92]

Aftermath

The Queen considered it a victory.[92] Crowds of Londoners celebrated exuberantly in the streets; the windows of government supporters were smashed, and the offices of newspapers that had supported the King were set alight.[93] Similar scenes occurred throughout the United Kingdom.[94] On 29 November, Caroline attended a service of thanksgiving at St Paul's Cathedral with the Lord Mayor of London, much to the dismay of the Dean of St Paul's. Vast crowds turned out to see her; estimates of the number in the crowd vary between 50,000 and 500,000.[95] Nevertheless, she was still barred from George's coronation at Westminster Abbey on 19 July 1821. She fell ill and died three weeks later. Her husband did not attend her funeral, and her body was returned to Brunswick for burial.[96]

With the failure of the bill, the radicals largely lost Caroline as a figurehead of the reform movement, since they were stripped of a cause and Caroline had no further need of them as allies.[97] Once the scandal had died down, the loyalist pro-King party had a resurgence, and became more vocal.[98] It took over a decade and the death of King George IV, for the reform movement to gain sufficient ground to force through Parliament the Reform Act 1832, which regulated the franchise throughout the United Kingdom.

References

- ^ Baker, Kenneth, George IV: A Life in Caricature (London: Thames & Hudson, 2005, ISBN 978-0-500-25127-0) p. 166

- ^ Robins, Jane (2006). Rebel Queen: How the Trial of Caroline Brought England to the Brink of Revolution. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7434-7826-7. p.132.

- ^ Pronounced "broom", "brew-am" or "bro'am"

- ^ Robins, p.134.

- ^ Robins, p. 137

- ^ Robins, p. 138

- ^ Robins, pp. 141–142

- ^ Robins, p. 140

- ^ Robins, p. 142

- ^ Robins, p. 123

- ^ Robins, pp. 142–143

- ^ Quoted in Robins, p. 143

- ^ Robins, p. 149

- ^ Robins, pp. 151–157

- ^ Robins, pp. 158–160

- ^ Robins, p. 160

- ^ Queen Caroline in The Times, 2 August 1820

- ^ Robins, pp. 162–163

- ^ Robins, p. 164

- ^ Robins, pp. 165–169

- ^ Robins, p. 170

- ^ Robins, p. 171

- ^ a b Robins, pp. 172–174

- ^ Thomas Moore's Memoirs, (London, 1853) vol. III, p. 149, quoted in Robins, p. 176

- ^ Robins, pp. 181–182

- ^ Robins, pp. 182–184

- ^ Gifford's speech quoted in Robins, pp. 184–185

- ^ Robins, p. 185

- ^ Leigh Hunt, Correspondence, vol. I, p. 156, quoted in Robins, p. 186

- ^ Robins, pp 187–188

- ^ Robins, pp. 188–191

- ^ Robins, p. 191

- ^ The Journal of the Hon. Henry Edward Fox, afterwards fourth and last Lord Holland, 1818–1830, p.41, quoted in Robins, p. 192.

- ^ a b The Times, 23 August 1820

- ^ As recorded in Fox's journal, the letters of Sara Hutchinson, and public placards quoted in The Times newspaper, all quoted in Robins, pp. 192-193

- ^ Denman's journal, quoted in Robins, p. 196

- ^ a b Robins, p. 224

- ^ Letter from Princess Lieven to Klemens Wenzel, Prince von Metternich in Quennell, Peter (editor) The Private Letters of Princess Lieven to Prince Metternich 1820–1826 (London: John Murray, 1948), p. 54, quoted in Robins, pp. 223–224

- ^ Majocchi's testimony quoted in Robins, p. 193

- ^ Majocchi's testimony quoted in Robins, p.194

- ^ Majocchi's testimony quoted in Robins, p. 196

- ^ Robins, pp. 196, 213–214

- ^ Robins, pp. 197–199

- ^ Robins, p. 199

- ^ a b Robins, p. 201

- ^ Papers in Royal Archives (Geo Add 10/1, bundle 5) quoted in Robins, p.201.

- ^ Robins, p. 202

- ^ Letter from Princess Lieven to Prince Metternich in Quennell, Peter (editor) The Private Letters of Princess Lieven to Prince Metternich 1820–1826 (London: John Murray, 1948), p. 51, quoted in Robins, p. 212

- ^ Robins, pp. 212–213

- ^ The Journal of Mrs Arbuthnot 1820–1832. vol. I, p.35, quoted in Robins, p. 213

- ^ Robins, p. 216

- ^ Robins, p. 218

- ^ a b c Robins, p. 217

- ^ Robins, p. 232

- ^ Robins, pp. 224–225

- ^ The Times 6 September 1820

- ^ a b Aspinall, A., Letters of King George IV 1812–1830 (Cambridge University Press, vol.II, 1938), pp.361–363, quoted in Robins, pp. 226–227

- ^ Robins, p. 237

- ^ Denman's Memoirs quoted in Robins, p. 227

- ^ Denman's Memoirs quoted in Robins, p. 228

- ^ Papers in the Royal Archives (Geo/Box11/3, bundle 36) quoted in Robins, p. 230

- ^ Papers in the Royal Archives (Geo Add 11/1, bundle 32C) quoted in Robins, p. 230

- ^ Charles Cavendish Fulke Greville in Strachey, Lytton; Fulford, Roger (editors) (1938). The Greville Memoirs, 1814–1860. London: Macmillan. vol.I, p. 105 quoted in Robins, p. 250

- ^ Denman's Memoirs, vol.I, p. 169 quoted in Robins, p. 250

- ^ Letter from William Vizard, Queen Caroline's solicitor, to James Brougham, Royal Archives Geo 11/3, bundle 37, quoted in Robins, p.251.

- ^ Creevey Papers edited by Sir Herbert Maxwell, 7th Baronet (1903). London: John Murray. vol.I, pp.321–322 quoted in Robins, p.251.

- ^ Robins, pp.247–248.

- ^ Robins, pp.248–249.

- ^ Robins, p.249.

- ^ Robins, p.250.

- ^ Robins, pp.251–258, 271.

- ^ Aspinall, A. (1938). Letters of King George IV 1812–1830 Cambridge University Press. vol.II, pp.371 quoted in Robins, p.254.

- ^ Robins, p.252.

- ^ Courier newspaper, 7 October 1820, quoted in Robins, p.254.

- ^ Robins, pp.256–257.

- ^ Martigner's testimony quoted in Robins, p.271.

- ^ Robins, p.258.

- ^ Creevey and Lieven separately quoted in Robins, pp.260–261.

- ^ Robins, pp.262–263.

- ^ Robins, p.267.

- ^ a b Robins, p.268.

- ^ Robins, p.269.

- ^ Robins, p.270.

- ^ Robins, pp.272–277.

- ^ Robins, pp.278–279.

- ^ Robins, p.280.

- ^ Robins, pp.281–283.

- ^ Robins, p.285.

- ^ Letter from Princess Lieven to Prince Metternich in Quennell, Peter (editor) (1948) The Private Letters of Princess Lieven to Prince Metternich 1820–1826. London: John Murray. p.40 quoted in Robins, p.285.

- ^ Robins, p.286.

- ^ The Journal of Mrs Arbuthnot 1820–1832. vol.I, p.52 quoted in Robins, pp.286–287.

- ^ a b Robins, p.287.

- ^ Robins, pp.289–291.

- ^ Robins, pp.291–293.

- ^ Robins, pp.295–296.

- ^ Robins, pp.309–318.

- ^ Robins, p.300.

- ^ Robins, pp.301–302.

Further reading

- Shingleton HM. The Tumultuous Marriage of The Prince and Princess of Wales. ACOG Clinical Review (2006) 11(6):13-6.