Petticoat affair

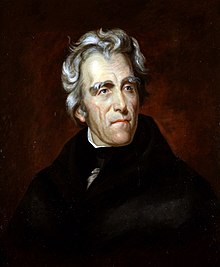

The Petticoat affair (also known as the Eaton affair) was a political scandal involving members of President Andrew Jackson's Cabinet and their wives, from 1829 to 1831. Led by Floride Calhoun, wife of Vice President John C. Calhoun, these women, dubbed the "Petticoats", socially ostracized Secretary of War John Eaton and his wife, Peggy Eaton, over disapproval of the circumstances surrounding the Eatons' marriage and what they deemed her failure to meet the "moral standards of a Cabinet Wife".

The Petticoat affair rattled the entire Jackson administration and eventually led to the resignations of Vice President Calhoun (the first such departure in U.S. history) and all but one Cabinet member. The ordeal facilitated Martin Van Buren's rise to the presidency and was in part responsible for reducing Calhoun's stature from that of a nationwide political figure with presidential aspirations into a major sectional leader of the Southern United States.

Background

[edit]Margaret "Peggy" Eaton was the eldest daughter of William O'Neill, owner of the Franklin House, a boarding house and tavern located in Washington, D.C., a short distance from the White House, that was a well-known social hub popular with politicians and military officials. Peggy was well-educated for a woman of that era – she studied French and was known for her ability to play the piano.[1] William T. Barry, who later served as Postmaster General, wrote "of a charming little girl ... who very frequently plays the piano, and entertains us with agreeable songs".[2]

As a young girl, her reputation had already begun to come under scrutiny because of her employment in a bar frequented by men, as well as her casual bantering with the boarding house's clientele. In her later years, Peggy reminisced, "While I was still in pantalettes and rolling hoops with other girls, I had the attention of men, young and old; enough to turn a girl's head."[3]

When Peggy was 15 years old, her father intervened to prevent her attempt to elope with an Army officer.[4] In 1816, the 17-year-old Peggy married John B. Timberlake, a purser in the United States Navy.[5] Timberlake, aged 39, had a reputation as a drunkard and was heavily in debt.[5] The Timberlakes became acquainted with John Eaton in 1818.[6] At the time, Eaton was a wealthy 28-year-old widower and newly elected U.S. Senator from Tennessee, despite not yet having reached the constitutionally-mandated minimum age of 30.[7] He was also a long-time friend of Andrew Jackson.[8]

Once Timberlake told Eaton of his financial troubles, Eaton unsuccessfully attempted to have the Senate pass legislation that would authorize payment of the debts Timberlake had accrued during his Naval service. Eventually, Eaton paid Timberlake's debts and procured him a lucrative posting to the U.S. Navy's Mediterranean Squadron; many rumormongers asserted that Eaton aided Timberlake as a means to remove him from Washington, in order for Eaton to socialize with Peggy.

While with the Mediterranean Squadron, Timberlake died on April 2, 1828. This served to fuel new rumors throughout Washington, suggesting he had taken his own life as the result of Eaton's supposed affair with Peggy.[5] Medical examiners concluded Timberlake had died of pneumonia, brought on by pulmonary disease.[1]

Controversy

[edit]| External videos | |

|---|---|

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Military career Presidential aspirations 7th President of the United States First term Second term Post-presidency  |

||

Jackson was elected president in 1828, with his term set to begin on March 4, 1829. He was reportedly fond of Peggy Timberlake and encouraged Eaton to marry her.[9] They were wed on January 1, 1829,[10] only nine months after her husband's death. Customarily, it would have been considered proper for their marriage to have followed a longer mourning period.[11]

Historian John F. Marszalek explains his opinion on the "real reasons Washington society found Peggy unacceptable":

She did not know her place; she forthrightly spoke up about anything that came to her mind, even topics of which women were supposed to be ignorant. She thrust herself into the world in a manner inappropriate for a woman. ... Accept her, and society was in danger of disruption. Accept this uncouth, impure, forward, worldly woman, and the wall of virtue and morality would be breached and society would have no further defenses against the forces of frightening change. Margaret Eaton was not that important in herself; it was what she represented that constituted the threat. Proper women had no choice; they had to prevent her acceptance into society as part of their defense of that society's morality.[12]

When Jackson assumed the presidency, he appointed Eaton as Secretary of War. Floride Calhoun, Second Lady of the United States, led the wives of other Washington political figures, mostly those of Jackson's cabinet members, in an "anti-Peggy" coalition, which served to shun the Eatons socially and publicly. The women refused to pay courtesy calls to the Eatons at their home and to receive them as visitors, and denied them invitations to parties and other social events.[13]

Emily Donelson, niece of Andrew Jackson's late wife Rachel Donelson Robards and the wife of Jackson's adopted son and confidant Andrew Jackson Donelson, served as Jackson's "surrogate First Lady".[14][15] Emily Donelson chose to side with the Calhoun faction, which led Jackson to replace her with his daughter-in-law Sarah Yorke Jackson as his official hostess.[16] Secretary of State Martin Van Buren was a widower and the only unmarried member of the Cabinet; he raised himself in Jackson's esteem by aligning himself with the Eatons.[17]

Jackson's sympathy for the Eatons stemmed in part from his late wife Rachel being the subject of innuendo during the presidential campaign, when questions arose as to whether her first marriage had been legally ended before she married Jackson. Jackson believed these attacks were the cause of Rachel's death on December 22, 1828, several weeks after his election to the presidency.[18][19]

Eaton's entry into a high-profile Cabinet post helped intensify the opposition of Mrs. Calhoun's group. In addition, Calhoun was becoming the focal point of opposition to Jackson; Calhoun's supporters opposed a second term for Jackson because they wanted Calhoun elected president. In addition, Jackson favored and Calhoun opposed the protective tariff that came to be known as the Tariff of Abominations. U.S. tariffs on imported goods generally favored Northern industries by limiting competition, but Southerners opposed them because the tariffs raised the price of finished goods but not the raw materials produced in the South.

The dispute over the tariff led to the nullification crisis of 1832, with Southerners – including Calhoun – arguing that states could refuse to obey federal laws to which they objected, even to the point of secession from the Union, while Jackson vowed to prevent secession and preserve the Union at any cost. Because Calhoun was the most visible opponent of the Jackson administration, Jackson felt that Calhoun and other anti-Jackson officials were fanning the flames of the Peggy Eaton controversy in an attempt to gain political leverage.[1] Duff Green, a Calhoun protégé and editor of the United States Telegraph, accused Eaton of secretly working to have pro-Calhoun Cabinet members Samuel D. Ingham and John Branch removed from their positions.[20]

Eaton took his revenge on Calhoun. In 1830, reports had emerged which accurately stated that while Calhoun was Secretary of War and Jackson was a major general in the U.S. Army, Calhoun had favored censuring Jackson for his 1818 invasion of Florida. These reports infuriated Jackson.[21] Calhoun asked Eaton to approach Jackson about the possibility of Calhoun publishing his correspondence with Jackson at the time of the Seminole War. Eaton did nothing. This caused Calhoun to believe that Jackson had approved the publication of the letters.[22] Calhoun published them in the Telegraph.[23] Their publication gave the appearance of Calhoun trying to justify himself against a conspiracy, which further enraged the president.[22]

Resolution

[edit]The dispute was finally resolved when Van Buren offered to resign, giving Jackson the opportunity to reorganize his Cabinet by asking for the resignations of the anti-Eaton Cabinet members. Postmaster General William T. Barry was the lone Cabinet member to stay, and Eaton eventually received appointments that took him away from Washington, first as governor of Florida Territory, and then as minister to Spain.

On June 17, the day before Eaton formally resigned, a story appeared in the Telegraph stating that it had been "proved" that the families of Ingham, Branch, and Attorney General John M. Berrien had refused to associate with Mr. Eaton. Eaton wrote to all three men demanding that they answer for the article.[24] Ingham sent back a contemptuous letter stating that, while he was not the source for the article, the information was still true.[25] On June 18, Eaton challenged Ingham to a duel through Eaton's brother in law, Dr. Philip G. Randolph, who visited Ingham twice and the second time threatened him with personal harm if he did not comply with Eaton's demands. Randolph was dismissed, and the next morning Ingham sent a note to Eaton discourteously declining the invitation[26] and describing his situation as one of "pity and contempt". Eaton wrote a letter back to Ingham accusing him of cowardice.[27] Ingham was then informed that Eaton, Randolph, and others were looking to assault him. He gathered together his own bodyguard and was not immediately molested. However, he reported that for the next two nights Eaton and his men continued to lurk about his dwelling and threaten him. He then left the city and returned safely to his home.[26] Ingham communicated to Jackson his version of what took place, and Jackson asked Eaton to explain himself. Eaton admitted that he "passed by" the place where Ingham had been staying, "but at no point attempted to enter ... or besiege it".[28]

Aftermath

[edit]

In 1832, Jackson nominated Van Buren as minister to Great Britain. Calhoun killed the nomination with a tie-breaking vote against it, claiming his act would "...kill him, sir, kill him dead. He will never kick, sir, never kick."[29] However, Calhoun only made Van Buren seem the victim of petty politics, which were rooted largely in the Eaton controversy. This raised Van Buren even further in Jackson's esteem.[30] Van Buren succeeded Calhoun as vice president when Jackson won a second term in 1832.[31] Van Buren thus became the de facto heir to the presidency and succeeded Jackson in 1837.

Although Emily Donelson had supported Floride Calhoun, after the controversy ended Jackson asked her to return as his official hostess; she resumed these duties in conjunction with Sarah Yorke Jackson until returning to Tennessee after contracting tuberculosis, leaving Sarah Yorke Jackson to serve alone as Jackson's hostess.

John Calhoun resigned as vice president shortly before the end of his term and returned with his wife to South Carolina.[32] Quickly elected to the U.S. Senate, he returned to Washington not as a national leader with presidential prospects but as a regional leader who argued in favor of states' rights and the expansion of slavery.

In regard to the Petticoat affair, Jackson later remarked, "I [would] rather have live vermin on my back than the tongue of one of these Washington women on my reputation."[33] To Jackson, Peggy Eaton was just another of many wronged women whom over his lifetime he had known and defended. He believed that every woman he had defended in his life, including her, had been the victim of ulterior motives, so that political enemies could bring him down.[34]

Legacy

[edit]Historian Robert V. Remini said that "the entire Eaton affair might be termed infamous. It ruined reputations and terminated friendships. And it was all so needless."[28] Historian Kirsten E. Wood argues that it "was a national political issue, raising questions of manhood, womanhood, presidential power, politics, and morality."[35]

The 1936 film The Gorgeous Hussy is a fictionalized account of the Petticoat affair. It features Joan Crawford as Peggy O'Neill, Robert Taylor as John Timberlake, Lionel Barrymore as Andrew Jackson, and Franchot Tone as John Eaton.[36][37]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Andrew Jackson: The Petticoat Affair, Scandal in Jackson's White House". History Net. 12 June 2006. Retrieved August 4, 2009.

- ^ Marszalek 2000, p. 1835.

- ^ Wood, Kristen E. (March 1, 1997). "One Woman so Dangerous to Public Morals". Journal of the Early Republic. 17 (2). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press: 237–75. doi:10.2307/3124447. JSTOR 3124447.

- ^ Watson, Robert P. (2012). Affairs of State: The Untold History of Presidential Love, Sex, and Scandal, 1789–1900. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 192. ISBN 978-1-4422-1834-5.

- ^ a b c McCrary, Royce C.; Ingham, S. D. (1976). ""The Long Agony is Nearly over": Samuel D. Ingham Reports on the Dissolution of Andrew Jackson's First Cabinet". The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. 100 (2): 231–242. JSTOR 20091054.

- ^ Gerson, Noel Bertram (1974). That Eaton Woman: In Defense of Peggy O'Neale Eaton. Barre, Massachusetts: Barre Publishing. p. 25. ISBN 9780517517765.

- ^ Baker, Richard A. (2006). 200 Notable Days: Senate Stories, 1787 to 2002. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-16-076331-1.

- ^ Belohlavek, John M. (2016). Andrew Jackson: Principle and Prejudice. New York City: Routledge. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-415-84485-7.

- ^ Humes, James C. (1992). My Fellow Americans: Presidential Addresses that Shaped History. New York City: Praeger. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-275-93507-8.

- ^ Grimmett, Richard F. (2009). St. John's Church, Lafayette Square: The History and Heritage of the Church of the Presidents, Washington, DC. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Mill City Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-1-934248-53-9.

- ^ Nester, William (2013). The Age of Jackson and the Art of American Power, 1815–1848. Washington, DC: Potomac Books. p. 107. ISBN 978-1-61234-605-2.

- ^ Marszalek 2000, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Manweller, Mathew (2012). Chronology of the U.S. Presidency. Vol. 1. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 232. ISBN 978-1-59884-645-4.

- ^ Chronology of the U.S. Presidency, p. 245.

- ^ Strock, Ian Randal (2016). Ranking the First Ladies: True Tales and Trivia, from Martha Washington to Michelle Obama. New York: Carrel Books. ISBN 978-1-63144-058-8.

- ^ Ranking the First Ladies

- ^ Greenstein, Fred I. (2009). Inventing the Job of President: Leadership Style from George Washington to Andrew Jackson. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-691-13358-4.

- ^ Gripsrud, Jostein (2010). Relocating Television: Television in the Digital Context. New York: Routledge. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-415-56452-6.

- ^ Mattes, Kyle; Redlawsk, David P. (2014). The Positive Case for Negative Campaigning. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-226-20202-0.

- ^ Snelling 1831, p. 194.

- ^ Cheathem 2008, p. 29.

- ^ a b Remini 1981, pp. 306–07.

- ^ "John C. Calhoun, 7th Vice President (1825–1832)". United States Senate. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- ^ Snelling 1831, p. 199.

- ^ Snelling 1831, pp. 199–200.

- ^ a b Snelling 1831, p. 200.

- ^ Parton 1860, p. 366.

- ^ a b Remini 1981, p. 320.

- ^ Latner 2002, p. 108.

- ^ Meacham 2008, pp. 171–175.

- ^ Woolley, John; Peters, Gerhard. "Election of 1832". American Presidency Project. Retrieved July 20, 2017.

- ^ Cheatham, Mark R. and Peter C. Mancall, eds., Jacksonian and Antebellum Age: People and Perspectives, ABC-CLIO, 2008, 30-32.

- ^ Widmer, Edward L. 2005. Martin Van Buren: The American Presidents Series, The 8th President, 1837–1841. Time Books. ISBN 978-0-7862-7612-7

- ^ Marszalek 2000, p. 238.

- ^ Wills, Matthew (2019-12-20). "The Mrs. Eaton Affair". JSTOR Daily. Retrieved 2020-05-05.

- ^ Nugent, Frank S., "The Gorgeous Hussy (1936) Democratic Unconvention in 'The Gorgeous Hussy,' at the Capitol -- 'A Son Comes Home,' at the Rialto," movie review, The New York Times, 5 September 1936. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- ^ Schwarz, Frederic D., "1831: That Eaton Woman," American Heritage, April/May 2006, Vol. 57. No. 2 (Subscription only.) Retrieved 29 December 2015.

Bibliography

[edit]- Cheathem, Mark Renfred (2008). Jacksonian and Antebellum Age: People and Perspectives. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-017-9.

- Latner, Richard B. (2002). "Andrew Jackson". In Graff, Henry (ed.). The Presidents: A Reference History (7th ed.).

- Marszalek, John F. (2000) [1997]. The Petticoat Affair: Manners, Mutiny, and Sex in Andrew Jackson's White House. Baton Rouge: LSU Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-2634-9.

- Meacham, Jon (2008). American Lion: Andrew Jackson in the White House. New York: Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8129-7346-4.

- Parton, James (1860). Life of Andrew Jackson, Volume 3. New York, NY: Mason Brothers. p. 648.

- Remini, Robert V. (1981). Andrew Jackson and the Course of American Freedom, 1822–1832. New York: Harper & Row Publishers, Inc. ISBN 978-0-8018-5913-7.

- Snelling, William Joseph (1831). A Brief and Impartial History of the Life and Actions of Andrew Jackson. Boston, MA: Stimpson & Clapp. p. 164.

- Wood, Kirsten E. “‘One Woman so Dangerous to Public Morals’: Gender and Power in the Eaton Affair,” Journal of the Early Republic 17 (Summer 1997): 237–275.

External links

[edit]- "Andrew Jackson and the Tavern-Keeper's Daughter", Women's History

- Andrew Jackson on the Web: Petticoat Affair

- J. Kingston Pierce, "Andrew Jackson's 'Petticoat Affair'", The History Net, June 1999

- This American Life, #485 "Surrogates", Act One: Petticoats in a Twist, (January 25, 2013). Sarah Koenig talks with historian Nancy Tomes about the Petticoat Affair.