Port Bonython

| Port Bonython South Australia | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Port Bonython gas-loading wharf with Santos' gas fractionation plant in the background. | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

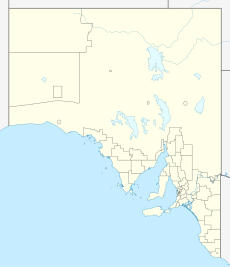

| Coordinates | 32°59′30″S 137°45′50″E / 32.99167°S 137.76389°E | ||||||||||||||

| Population | 14 (SAL 2016)[1][2] | ||||||||||||||

| Established | circa 1982 | ||||||||||||||

| Postcode(s) | 5601 | ||||||||||||||

| Time zone | ACST (UTC+9:30) | ||||||||||||||

| • Summer (DST) | ACDT (UTC+10:30) | ||||||||||||||

| Location | 221 km (137 mi) from Adelaide CBD | ||||||||||||||

| LGA(s) | City of Whyalla | ||||||||||||||

| State electorate(s) | Giles[3] | ||||||||||||||

| Federal division(s) | Grey[4] | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

Port Bonython is the location of a deepwater port, gas fractionation plant and diesel storage facility west of Point Lowly in the Upper Spencer Gulf region of South Australia.[5] It lies 16 km east-northeast of Whyalla, South Australia and approximately 370 km north-west of the State's capital city, Adelaide. The existing wharf is 2.4 kilometres long and is capable of berthing small Capesize ships with a maximum capacity of 110,000 tonnes. The wharf was established in 1982 and named after John Bonython, the founding chairman of Santos. The structure is leased to Santos by the Government of South Australia and is used for the export of hydrocarbon products. An oil spill at Port Bonython in 1992 resulted in loss of bird life and damage to mangrove habitats to the west and southwest of Port Pirie.

Overview

[edit]A gas fractionation plant operated by Santos was established at Port Bonython in 1982. The plant's refinery and tank farm complex receive crude oil and gas from the Cooper Basin in outback South Australia for processing and distribution. Port Bonython is the terminus of the Moomba to Port Bonython Liquids Pipeline which is 659 km long.[6] From Port Bonython, Santos freights hydrocarbon products by sea to customers across the Asia-Pacific region.[citation needed]

A 2.4 km long wharf was constructed and purchased by the Government of South Australia for $48.2 million in 1983.[7] First shipments from the facility were made that year.[8] It was officially opened on 5 September 1984 by the South Australian Premier John Bannon.[9]

The jetty is licensed to Santos under the Stony Point (Liquids Project) Ratification Act, 1981 and the State Government has an obligation to maintain the jetty for the life of the indenture. In 2010, Cabinet committed $29.9 million to its refurbishment.[7]

A major oil spill occurred at Port Bonython during the berthing of the tanker Era in 1992. Her hull was pierced by a tugboat and approximately 300 tonnes of heavy bunker fuel leaked into Spencer Gulf. The spill response used chemical dispersants including Corexit and the remaining slick resulted in loss of bird life and damage to mangrove habitats and tidal creeks.[citation needed]

In May 2016, Port Bonython Fuels was commissioned, ending Santos's prior claim as the only established industrial presence in the area. Several other development proposals from other companies have been announced then subsequently abandoned.[citation needed]

In 2020, Port Bonython was named by the Government of South Australia as a potential location for the development of hydrogen export facilities to facilitate the expansion of the state's growing utility-scale renewable energy sector.[10]

Proposed Port Bonython Mineral Precinct

[edit]Port Bonython was chosen as the site of a future mineral export precinct, facilitated by the Rann government. Concept plans included an iron ore export facility, a fuel distribution hub and a seawater desalination plant. Water produced by the proposed desalination plant would be piped overland, 300 km north to the Olympic Dam mine for the exclusive use of BHP. As of 2018, Port Bonython Fuels has been constructed and commissioned, the desalination plant has been abandoned and the iron ore export facility was abandoned without announcement.

Port Bonython Fuels

[edit]

A fuel distribution hub and micro-refinery project known as Port Bonython Fuels was initially proposed by Scott's Transport and Stuart Petroleum in 2007.[11] The two stage development was designed to provide a billion litres of diesel per year by road freight to mining companies around South Australia.[12] The project's terrestrial footprint is comparable to Santos' facility.

The project was deemed to be public infrastructure and awarded 'Crown-sponsored Status' by the South Australian Government. The development application was approved by the Development Assessment Commission and the Minister for Planning Paul Holloway in 2010. The project documentation is not publicly available.

Port Bonython Fuels[13] was sold by Senex Energy to Mitsubishi Corporation in two stages. Mitsubishi first purchased a 90% stake in 2012,[12] then the remaining 10% in 2013. Port Bonython Fuels Ltd is now a wholly owned subsidiary of Mitsubishi Corporation.[14]

In 2014, it was announced that Port Bonython Fuels was expected to commence construction in 2015. Opposition to the development has called for the proposed facility's relocation 20 km west, adjacent to the Lincoln Highway.[15] The facility was commissioned in May 2016 and is owned by IOR Terminals and operated by Coogee Chemicals. It is open twenty-four hours-a-day, seven days-a-week and services tanker trucks of various classification, the largest being A-Triple size. The facility has increased shipping traffic to the existing Port Bonython wharf, where it receives imported liquid hydrocarbons. The facility includes 81ML of diesel storage (three 27ML tanks) and a two-bay gantry, each bay with three arms (2,400 Lpm per arm).[16]

Abandoned projects

[edit]BHP Desalination Plant

[edit]Resource company BHP proposed to construct a reverse-osmosis seawater desalination plant at Port Bonython to provide water for the expansion of the Olympic Dam copper and uranium mine. The plant was approved by both State and Federal Governments in October, 2011. The plant had an approved capacity of up to 280 megalitres of produced water per day, or 137 gigalitres per year. At full capacity, this would result in 370 megalitres of waste brine with elevated salinity returned to the sea off Point Lowly.

During the preparation of the Olympic Dam Expansion Draft Environmental Impact Statement, scientists discovered that the region's population of Giant Australian Cuttlefish was genetically distinct and that it was vulnerable to increased salinity and changes in pH, particularly during embryo development.[citation needed]

Numerous people expressed concern about the potential impact of the plant on Spencer Gulf's salinity including prawn fishermen,[17] tuna growers,[18] scientists[17][19] and environmentalists.[20]

A small scale pilot desalination plant was established at Port Bonython and operated from 2007 to 2010. The pilot plant was established and operated by Veolia Water Solutions and Technology and a monitoring station was operated by Water Data Services.[21]

The proposal to construct a desalination plant was ultimately abandoned after the company decided to expand the mine using existing methods, rather than reconfiguring the mine to an open cut.[22] If constructed, the plant would have been the second largest in Australia after the Victorian Desalination Plant.[23]

Port Bonython Bulk Commodities Export Facility

[edit]After identifying shortfalls in bulk commodities export infrastructure, four emerging mining companies formed the Port Bonython Bulk Users Group in 2008. A competitive tendering process to plan, build and operate the common user Port Bonython Bulk Commodities Export Facility was facilitated by the South Australian Government with the contract awarded in 2008.[24]

An Environmental Impact Statement for the Port Bonython Bulk Commodities Export Facility was published by the Spencer Gulf Port Link consortium in 2013. Public submissions closed on 18 November 2013.[25] The time period for consideration of the Federal environmental approval was extended at least four times, and was anticipated on or before 31 December 2014. As of August 2018 no decision regarding Federal environmental approval for the facility has been made.[26] No final decision was ever published.[27]

The proposed bulk commodities export facility was intended to be open access and managed by consortium. The consortium included Flinders Port Holdings, Australian Rail Track Corporation, Leighton Contractors and Macquarie Capital.

Prospective miners with iron ore deposits in the state's far north, including within the Woomera Protected Area were the most likely to utilize the facility, were it ever constructed. WPG Resources is one such company.[28] BHP also expressed interest in considering Port Bonython for the potential future export of copper concentrates to China, were the Olympic Dam mine to expand to an open cut operation.[29] All four mining companies that formed the Port Bonython Bulk Users Group either found alternative pathways for iron ore export or abandoned their iron ore prospects entirely. WPG Resources and IMX Resources successfully exported from other ports while Ironclad Mining and Centrex Metals did not proceed to mine development.[30]

Other projects

[edit]An liquefied natural gas processing plant was proposed by Beach Energy and its Japanese partners Itochu in 2010,[31] but was subsequently abandoned. In 2011, a plan to develop a Technical Ammonium Nitrate (TAN) plant was proposed by Deepak Fertilizers[32] and was abandoned the following year owing partly to the location.[33] The TAN plant proposal prompted accusations of State government deception, made by the community action group, Save Point Lowly.[34]

Upper Spencer Gulf Marine Park

[edit]

Waters adjacent to Port Bonython fall within the Upper Spencer Gulf Marine Park's outer boundary. A sanctuary zone has been created for the protection of the Australian giant cuttlefish. It covers a section of inshore breeding habitat immediately to the west of the proposed Port Bonython Bulk Commodities Export Facility. This location is renown as one of South Australia's best scuba diving sites.[35]

An additional sanctuary zone exists at Fairway Bank, south of Port Bonython. It is located on the western side of the narrow shipping channel and may be subjected to impacts from moving Capesize vessels with limited under-keel clearance.

Special Purpose Areas are juxtaposed over sanctuary zones to allow for activity associated with significant economic development.

Shipping movements within the marine park were predicted to increase from approximately 360 per year to over 1000 by the year 2020, but this did not eventuate. Figures for shipping movement estimates did not include barge movements for transshipping activities. 32 barge movements are required to fill a single Panamax bulk carrier with iron ore.[36] BHP also intends to transport heavy equipment by barge to a future landing facility north of Fitzgerald Bay, in the northern reaches of the Upper Spencer Gulf Marine Park.[23]

Community response

[edit]Community action groups from Whyalla including Save Point Lowly, the Cuttlefish Coast Coalition and the Alternative Port Working Party have opposed the further industrialization of the Port Bonython and Point Lowly area in public, in formal submissions to Government and in the media.[37] Their position is that the social, recreational and environmental values of the area must be preserved for current and future generations. They have identified alternative locations for the same facilities which would retain employment and other economic benefits for Whyalla's citizens whilst greatly reducing the extent of community and environmental sacrifice.

Transport and access

[edit]Roads

[edit]Port Bonython Road provides the only access to the Port Bonython area. It is currently a shared use public road which provides access to the Australian Army's Cultana Training Area, Point Lowly lighthouse, beaches, boat ramp and numerous coastal homes and camp sites. It also provides access for divers and tourists who visit in May through September to view or swim with the Australian giant cuttlefish during their annual inshore breeding aggregation. A coastal road to the north exists, but it is controlled by the Australian Army and is permanently closed to the public. In 2016 a partnership between the state government and Port Bonython Fuels enabled the construction of a new road connecting Port Bonython Road with the popular cuttlefish tourism site at Stony Point.[38]

Railways

[edit]The Whyalla railway line connecting Whyalla to Port Augusta is standard gauge. The national standard gauge system extends from Port Augusta to Darwin, Perth, Adelaide and other regional towns. The separate and isolated BHP Whyalla Tramway narrow gauge railway connects Whyalla to Iron Knob and extends to Iron Duke and other iron ore mines of the Middleback Range. It is privately operated for the exclusive use of Arrium. Railways to Whyalla were originally built for BHP. A new rail link connecting Port Bonython to the Whyalla standard gauge line is a component of the Port Bonython Bulk Commodities Export Facility proposal.

A dual gauge balloon loop was constructed at Whyalla[39] to increase iron ore export capacity at the existing port there.

References

[edit]- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (27 June 2017). "Port Bonython (suburb and locality)". Australian Census 2016.

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (27 June 2017). "Port Bonython (suburb and locality)". Australian Census 2016 QuickStats. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ "District of Giles Background Profile". ELECTORAL COMMISSION SA. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- ^ "Federal electoral division of Grey, boundary gazetted 16 December 2011" (PDF). Australian Electoral Commission. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- ^ "Port Bonython: Australia, geographic coordinates, administrative division, map". Geographical Names. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ^ "Australia, New Zealand and Papua New Guinea Pipelines map - Crude Oil (petroleum) pipelines - Natural Gas pipelines - Products pipelines". Countries of the World. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- ^ a b FINAL REPORT - PORT BONYTHON JETTY REFURBISHMENT - 388TH REPORT OF THE PUBLIC WORKS COMMITTEE (PDF). Adelaide, South Australia: Government of South Australia. 2010. p. 4.

- ^ "Port Bonython Liquids Facilities (Stony Point)" BAM Clough. Accessed 2013-12-22.

- ^ "Huge petroleum project opened". Canberra Times. 6 September 1984. Retrieved 7 December 2014.

- ^ Australia, Premier of South (30 October 2020). "Hydrogen Prospectus shows epic future for SA Renewables". Premier of South Australia. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ^ "Scott Group and Stuart Petroleum in Diesel Refinery Link" Archived 2009-10-04 at the Wayback Machine Railexpress.com.au (2007-08-09). Retrieved 2013-11-17.

- ^ a b Proactive Investors Australia "Senex Energy selling Port Bonython Fuels Terminal project to Mitsubishi Corporation" - accessed 2013.11.01

- ^ "Port Bonython Fuels".

- ^ "Port Bonython to break bottleneck" InBusiness No.40 (April 2008). Retrieved 2013-11-01.

- ^ "Environmental fears fuel port bonython terminal opposition". ABC. 4 September 2014. Retrieved 5 September 2014.

- ^ "Port Bonython Fuel Terminal | IOR Terminals". www.iorterminals.com.au. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ a b "Prawn fishers worried about BHP's plans". ABC Rural. 6 July 2011. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ Kapelle, Liza (16 November 2011). "Bluefin tuna farm scales up". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ Salleh, Anna (30 April 2009). "Big cuttlefish 'at risk' from desalination". ABC Science. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ "BHP Desalination Plant: A Threat of Olympic Proportions". The Wilderness Society. 23 October 2013. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ "Olympic Dam Expansion Supplementary Environmental Impact Statement 2011" (PDF). BHP Billiton. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ "Olympic Dam: Major overhaul - The Australian Mining Review". The Australian Mining Review. 30 August 2017. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ a b BHP Billiton Ltd "Olympic Dam Draft Environmental Impact Statement 2009" ISBN 978-0-9806218-0-8

- ^ http://www.spencergulfportlink.com.au/ Archived 4 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine (accessed 31 October 2013)

- ^ http://www.spencergulfportlink.com.au/ Archived 4 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine (accessed 31 October 2013)

- ^ "Notification of extension to time in which to make a decision whether to approve a controlled action" (PDF). Australian Government.

- ^ "EPBC Referral detail - Spencer Gulf Port Link/Transport - water/Stoney Point, Eyre Pennisula[sic]", SA/SA/Port Bonython iron ore bulk comodities export facility on Eyre Peninsula" Department of the Environment, Australian Government (Accessed 2014-06-30)

- ^ "SA port project precedes a storm of iron ore export activity". The Age. Melbourne. 28 July 2008. Archived from the original on 7 July 2012.

- ^ BHP Billiton Ltd "Olympic Dam Draft Environmental Impact Statement 2009" ISBN 978-0-9806218-0-8

- ^ "Port Bonython to break bottleneck" InBusiness No.40 (April 2008). Retrieved 2013-11-01.

- ^ Russell, Christopher (26 November 2010). "Beach Energy announces plans for billion-dollar LNG facility in South Australia". Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- ^ "No answers about ammonium nitrate". Whyalla News. 21 May 2012. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- ^ Latimer, Cole (30 August 2012). "Port Bonython explosive plant plan dropped". Mining Australia. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- ^ "SA Govt accused of ammonium nitrate plant deception". ABC. 19 April 2011. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- ^ Hutchison, Stuart (1 December 2001). "Travellin' South". Australasia Scuba Diver: 18–30.

- ^ Kirkman, Dr H. et al, "Upper Spencer Gulf Marine Park Regional Impact Statement" SA Government, Dept. of Environment, Water & Natural Resources (accessed 2013-11-02)

- ^ "APWP still fighting" Whyalla News (2013-11-05). Retrieved 2013-11-05.

- ^ "News - Improving Cuttlefish access". Whyalla. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ Balloon loop Archived 2013-12-03 at the Wayback Machine