Red knot

| Red knot | |

|---|---|

| |

| Calidris canutus rufa, breeding plumage | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | C. canutus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Calidris canutus (Linnaeus, 1758)

| |

| |

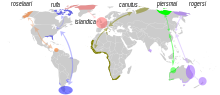

| Distribution and migration routes of the six subspecies of the Red Knot | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Tringa canutus | |

The red knot (Calidris canutus) (just knot in Europe) is a medium sized shorebird which breeds in tundra and the Arctic Cordillera in the far north of Canada, Europe, and Russia. It is a large member of the Calidris sandpipers, second only to the Great Knot.[2] Six subspecies are recognised.

Their diet varies according to season; arthropods and larvae are the preferred food items at the breeding grounds, while various hard-shelled molluscs are consumed at other feeding sites at other times. North American breeders migrate to coastal areas in Europe and South America, while the Eurasian populations winter in Africa, Papua New Guinea, Australia, and New Zealand. This species forms enormous flocks when not breeding.

Taxonomy, systematics, and evolution

This Red Knot was first described by Linnaeus in the landmark 1758 tenth edition of his Systema Naturae as Tringa canutus.[3] One theory is that it gets its name and species epithet from King Canute, Knot being another form of Canute; the name would refer to the knot's foraging along the tide line and the story of Canute and the tide.[4] Another etymology is that the name is onomatopoeic, based on the bird's grunting call note.[5]

Population relatedness and divergence

The diversification events may be associated with the Wisconsinan (Weichselian) glaciation 18,000 to 22,000 years ago; the opening of the ice-free corridor in North America 12,000 to 14,000 years ago; and the Holocene climatic optimum 7,000 to 9,000 years ago.[6] |

The Red Knot and the Great Knot were originally the only two species placed in the genus Calidris but many other species of sandpiper were subsequently added.[7] A 2004 study found that the genus was polyphyletic, and that the closest relative of the two knot species is the Surfbird (currently Aphriza virgata).[8]

There are six subspecies, in order of size;

- C. c. roselaari Tomkovich, 1990 (largest)

- C. c. rufa (Wilson, 1813)

- C. c. canutus (Linnaeus, 1758)

- C. c. islandica (Linnaeus, 1767)

- C. c. rogersi (Mathews, 1913)

- C. c. piersmai Tomkovich, 2001 (smallest)

Studies based on mitochondrial sequence divergence and models of paleoclimatic changes during the glacial cycles suggest that canutus is the most basal population, separating about 20,000 years ago (95% confidence interval: 60,000–4,000 years ago) with two distinct lineages of the American and Siberian breeders emerging about 12,000 years ago (with a 95% confidence interval: 45,000–3,500 years ago).[6][9]

Distribution and migration

In the breeding season the Red Knot has a circumpolar distribution in the high Arctic, then migrates to coasts around the world from 50° N to 58° S. The red knot has one of the longest migrations of any bird. Every year it travels more than 9,000 miles from the Arctic to the southern tip of South America.[10] The exact migration routes and wintering grounds of individual subspecies are still somewhat uncertain. The nominate race C. c. canutus breeds in the Taymyr Peninsula and possibly Yakutia and migrates to the Western Europe and then down to western and southern Africa. C. c. rogersi breeds in the Chukchi Peninsula in eastern Siberia, and winters in eastern Australia and New Zealand.[7] Small and declining numbers[11] of rogersi (but possibly of the later described piersmai) winter in the mudflats in the Gulf of Mannar and on the eastern coast[12] of India.[13] The recently split race C. c. piersmai breeds in the New Siberian Islands and winters in north-western Australia.[14] C. c. roselaari breeds in Wrangel Island in Siberia and north-western Alaska, and it apparently winters in Florida, Panama and Venezuela. C. c. rufa breeds in the Canadian low Arctic, and winters South America, and C. c. islandica breeds in the Canadian high Arctic as well as Greenland, and winters in Western Europe.

Birds wintering in west Africa were found to restrict their daily foraging to a range of just 2–16 km2 of intertidal area and roosted a single site for several months. In temperate regions such as the Wadden Sea they have been found to change roost sites each week and their feeding range may be as much as 800 km2 during the course of a week.[15]

B95, also known as Moonbird, is a noted individual of the subspecies C. c. rufa. A male, he has become famous amongst conservationists for his extreme longevity — he was aged at least 20 as of his last sighting in May 2014.[16]

Description and anatomy

An adult Red Knot is the second largest Calidris sandpiper, measuring 23–26 cm (9–10 in) long with a 47–53 cm (18.5–21 in) wingspan. The body shape is typical for the genus, with a small head and eyes, a short neck and a slightly tapering bill that is no longer than its head.[17] It has short dark legs and a medium thin dark bill. The winter, or basic, plumage becomes uniformly pale grey, and is similar between the sexes. The alternate, or breeding, plumage is mottled grey on top with a cinnamon face, throat and breast and light-coloured rear belly. The alternate plumage of females is similar to that of the male except it is slightly lighter and the eye-line is less distinct. canutus, islandica and piersmai are the "darker" subspecies. Subspecies rogersi has a lighter belly than either roselaari or piersmai, and rufa is the lightest in overall plumage. The transition from alternate to basic plumages begins at the breeding site but is most pronounced during the southwards migration. The molt to alternate plumage begins just prior to the northwards migration to the breeding grounds, but is mostly during the migration period.[17]

The large size, white wing bar and grey rump and tail make it easy to identify in flight. When feeding the short dark green legs give it a characteristic 'low-slung' appearance. When foraging singly, they rarely call, but when flying in a flock they make a low monosyllabic knutt and when migrating they utter a disyllabic knuup-knuup. They breed in the moist tundra during June to August. The display song of the male is a fluty poor-me. The display includes circling high with quivering wing beats and tumbling to the ground with the wings held upward. Both sexes incubate the eggs, but the female leaves parental care to the male once the eggs have hatched.[2]

Juvenile birds have distinctive submarginal lines and brown coverts during the first year. In the breeding season the males can be separated with difficulty (<80% accuracy in comparison to molecular methods[18]) based on the more even shade of the red underparts that extend towards the rear of the belly.[2]

The weight varies with subspecies, but ranges between 100 and 200 g (45–91 oz). Red Knots can double their weight prior to migration. Like many migratory birds they also reduce the size of their digestive organs prior to migration. The extent of the atrophy is not as pronounced as species like the Bar-tailed Godwit, probably because there are more opportunities to feed during migration for the Red Knot.[19] Red Knots are also able to change the size of their digestive organs seasonally. The size of the gizzard increases in thickness when feeding on harder foods on the wintering ground and decreases in size while feeding on softer foods in the breeding grounds. These changes can be very rapid, occurring in as little as six days.[20][21]

Behaviour

Diet and feeding

On the breeding grounds, Knots eat mostly spiders, arthropods, and larvae obtained by surface pecking, and on the wintering and migratory grounds they eat a variety of hard-shelled prey such as bivalves, gastropods and small crabs that are ingested whole and crushed by a muscular stomach.[17]

While feeding in mudflats during the winter and migration Red Knots are tactile feeders, probing for unseen prey in the mud. Their feeding techniques include the use of shallow probes into the mud while pacing along the shore. When the tide is ebbing, they tend to peck at the surface and in soft mud they may probe and plough forward with the bill inserted to about a centimetre depth. The bivalved mollusc Macoma is their preferred prey on European coasts, swallowing them whole and breaking them up in their gizzard.[22][23] In Delaware Bay, they feed in large numbers on the eggs of horseshoe crabs which spawn just as the birds arrive in mid-summer.[24] They are able to detect molluscs buried under wet sand from changes in the pressure of water that they sense using Herbst corpuscles in their bill.[25] Unlike many tactile feeders their visual field is not panoramic (allowing for an almost 360 degree field of view), as during the short breeding season they switch to being visual hunters of mobile, unconcealed prey, which are obtained by pecking.[26] Pecking is also used to obtain some surface foods in the wintering and migratory feeding grounds, such as the eggs of horseshoe crabs.[17]

Breeding

The Red Knot is territorial and seasonally monogamous; it is unknown if pairs remain together from season to season. Males and females breeding in Russia have been shown to exhibit site fidelity towards their breeding locales from year to year, but there is no evidence as to whether they exhibit territorial fidelity. Males arrive before females after migration and begin defending territories. As soon as males arrive, they begin displaying, and aggressively defending their territory from other males.[17]

The Red Knot nests on the ground, near water, and usually inland. The nest is a shallow scrape lined with leaves, lichens and moss.[10] Males construct three to five nest scrapes in their territories prior to the arrival of the females. The female lays three or more usually four eggs, apparently laid over the course of six days. The eggs measure 43 x 30 mm (1.7 x 1.2 in) in size and are ground coloured, light olive to deep olive buff, with a slight gloss. Both parents incubate the eggs, sharing the duties equally. The off duty parent forages in flocks with others of the same species. The incubation period lasting around 22 days. At early stages of incubation the adults are easily flushed from the nest by the presence of humans near the nest, and may not return for several hours after being flushed. However in later stages of incubation they will stay fast on the eggs. Hatching of the clutch is usually synchronised. The chicks are precocial at hatching, covered in downy cryptic feathers. The chicks and the parents move away from the nest within a day of hatching and begin foraging with their parents. The female leaves before the young fledge while the males stay on. After the young have fledged, the male begins his migration south and the young make their first migration on their own.[17]

Status

The Red Knot has an extensive range, estimated at 0.1–1.0 million square kilometres (0.04–0.38 million square miles), and a large population of about 1.1 million individuals. The species is not believed to approach the thresholds for the population decline criterion of the IUCN Red List (i.e., declining more than 30% in ten years or three generations), and is therefore evaluated as Least Concern.[1] However many local declines have been noted such as the dredging of intertidal flats for edible cockles (Cerastoderma edule) which led to reductions in the wintering of islandica in the Dutch Wadden Sea.[27] The quality of food at migratory stopover sites is a critical factor in their migration strategy.[28]

This is one of the species to which the Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds (AEWA) applies.[29] This commits signatories to regulate the taking of listed species or their eggs, to establish protected areas to conserve habitats for the listed species, to regulate hunting and to monitor the populations of the birds concerned.[30]

Threats to the American subspecies

Towards the end of the 19th century, large numbers of Red Knot were shot for food as they migrated through North America. It is hypothesized that more recently, the birds have become threatened as a result of commercial harvesting of horseshoe crabs in the Delaware Bay which began in the early 1990s. Delaware Bay is a critical stopover point during spring migration; the birds refuel by eating the eggs laid by these crabs (with little else to eat in the Delaware Bay).[31] If horseshoe crab abundance in the Bay is reduced there may fewer eggs to feed on which could negatively affect knot survival.[32][33][34]

In 2003, scientists projected that at its current rate of decline the American subspecies might become extinct as early as 2010, but as of April 2011 the subspecies is still extant. Several environmental groups have petitioned the U.S. government to list the birds as endangered,[24] but thus far their requests have not been granted. In New Jersey, state and local agencies are taking steps to protect these birds by limiting horseshoe crab harvesting and restricting beach access. In Delaware, a two-year ban on the harvesting of horseshoe crabs was enacted but struck down by a judge who cited insufficient evidence to justify the potential disruption to the fishing industry but a male-only harvest has been in place in recent years.[citation needed]

References

- ^ a b Template:IUCN

- ^ a b c Marchant, John; Hayman, Peter; Prater, Tony (1986). Shorebirds: an identification guide to the waders of the world. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 363–364. ISBN 0-395-37903-2.

- ^ Template:La icon Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata. Holmiae. (Laurentii Salvii). p. 149.

T. roftro laevi, pedibus cinerascentibus, remigibus primoribus ferratis.

- ^ Holloway, Joel Ellis (2003). Dictionary of Birds of the United States: Scientific and Common Names. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press. p. 50. ISBN 0-88192-600-0.

- ^ Higgins, Peter J.; Davies, S.J.J.F., ed. (1996). Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic Birds. Volume 3: Snipe to Pigeons. Melbourne, Victoria: Oxford University Press. pp. 224–32. ISBN 0-19-553070-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ a b Buehler, Deborah M.; Baker, Allan J.; Piersma, Theunis (2006). "Reconstructing palaeoflyways of the late Pleistocene and early Holocene Red Knot Calidris canutus" (PDF). Ardea. 94 (3): 485–98.

- ^ a b Piersma, T; van Gils, J; Wiersma, P (1996). "Scolopacidae(Sandpipers And Allies)". In Josep, del Hoyo; Andrew, Sargatal; Jordi, Christie (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World. Volume 3, Hoatzin To Auks. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions. p. 519. ISBN 84-87334-20-2.

- ^ Thomas, Gavin H. (2004). "A supertree approach to shorebird phylogeny". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 4 (28): 1–18. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-4-28. PMC 515296. PMID 15329156.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Buehler, Deborah M.; Baker, Allan J. (2005). "Population divergence times and historical demography in red knots and dunlins" (PDF). The Condor. 107 (3): 497–513. doi:10.1650/0010-5422(2005)107[0497:PDTAHD]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ a b "Red Knot Fact Sheet, Lincoln Park Zoo"

- ^ Boere, G.C., Galbraith, C.A. & Stroud, D.A. (eds). 2006. Waterbirds around the world. The Stationery Office, Edinburgh, UK.

- ^ Rao, P.; Mohapatra, K.K. (1993). "Occurrence of the Knot (Calidris canutus) in Andhra Pradesh in India". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 90 (3): 509.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Balachandran, S. (1998). "Population, status, moult, measurements, and subspecies of Knot Calidris canutus wintering in south India" (PDF). Wader Study Group Bull. 86: 44–47.

- ^ Tomkovich, P.S. (2001). "A new subspecies of Red Knot Calidris canutus from the New Siberian Islands". Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club. 121: 257–63.

- ^ Leyrer, Jutta; Spaans, Bernard; Camara, Mohamed; Piersma, Theunis (2006). "Small home ranges and high site fidelity in red knots (Calidris c. canutus) wintering on the Banc d'Arguin, Mauritania" (PDF). J. Ornithol. 147 (2): 376–84. doi:10.1007/s10336-005-0030-8.

- ^ Bauers, Sandy. "Globe-spanning bird B95 is back for another year". Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f Harrington, Brian (2001). "Red Knot". Birds of North America. Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology. doi:10.2173/bna.563. Retrieved 27 April 2009.

- ^ Baker, AJ (1999). "Molecular vs. phenotypic sexing in red knots" (PDF). The Condor. 101 (4). Cooper Ornithological Society: 887–893. doi:10.2307/1370083. JSTOR 1370083.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Piersma, Theunis (1998). "Phenotypic Flexibility during Migration: Optimization of Organ Size Contingent on the Risks and Rewards of Fueling and Flight?". Journal of Avian Biology. 29 (4). Blackwell Publishing: 511–20. doi:10.2307/3677170. JSTOR 3677170.

- ^ Dekinga, A.; Dietz MW; Koolhaas A; Piersma T (2001). "Time course and reversibility of changes in the gizzards of red knots alternately eating hard and soft food". Journal of Experimental Biology. 204 (12): 2167–73.

- ^ Piersma, Theunis (1999). "Reversible size-changes in stomachs of shorebirds: when, to what extent, and why?" (PDF). Acta Ornithologica. 34: 175–81.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Prater, A. J. (1972). "The Ecology of Morecambe Bay. III. The Food and Feeding Habits of Knot (Calidris canutus L.) in Morecambe Bay". Journal of Applied Ecology. 9 (1). British Ecological Society: 179–94. doi:10.2307/2402055. JSTOR 2402055.

- ^ Zwarts, L; Blomert, A-M (1992). "Why knot Calidris canutus take medium-sized Macoma balthica when six prey species are available" (PDF). Marine Ecol. Progress. Series. 83 (2–3): 113–28. doi:10.3354/meps083113.

- ^ a b "Petition to List the Red Knot (Caladris canutus rufa) as Endangered and Request for Emergency Listing under the Endangered Species Act" (PDF). Federal Wildlife Service. 2005-08-02. Retrieved 2009-03-27.

- ^ Piersma, Theunis (1998). "A new pressure sensory mechanism for prey detection in birds: the use of principles of seabed dynamics?" (PDF). Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 265 (1404): 1377–83. doi:10.1098/rspb.1998.0445.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Martin, Graham R.; Theunis Piersma (2009). "Vision and touch in relation to foraging and predator detection: insightful contrasts between a plover and a sandpiper". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 276 (1656): 437–45. doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.1110. PMC 2664340. PMID 18842546.

- ^ van Gils, Jan A (2006). "Shellfish Dredging Pushes a Flexible Avian Top Predator out of a Marine Protected Area". PLoS Biol. 4 (12): e376. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040376. PMC 1635749. PMID 17105350.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ van Gils, Jan A (2005). "Reinterpretation of gizzard sizes of red knots world-wide emphasises overriding importance of prey quality at migratory stopover sites". Proc. R. Soc. B. 272 (1581): 2609–2618. doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3245. PMC 1559986. PMID 16321783.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Annex 2: Waterbird species to which the Agreement applies" (PDF). Agreement on the conservation of African-Eurasian migratory Waterbirds (AEWA). AEWA. Retrieved 22 April 2008.

- ^ "Annex 3: Waterbird species to which the Agreement applies" (PDF). Agreement on the conservation of African-Eurasian migratory Waterbirds (AEWA). AEWA. Retrieved 22 April 2008.

- ^ Karpanty, Sarah (2006). "Horseshoe crab eggs determine red knot distribution in Delaware Bay". Journal of Wildlife Management. 70 (6): 1704–1710. doi:10.2193/0022-541X(2006)70[1704:HCEDRK]2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 4128104.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Baker, Allan J. (2004). "Rapid population decline in red knots: fitness consequences of decreased refueling rates and late arrival in Delaware Bay". Proceedings of the Royal Society. 271 (1541): 875–82. doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2663. PMC 1691665. PMID 15255108.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Niles, Lawrence J. et al. (2008) Status of the Red Knot (Calidris canutus rufa) in the Western Hemisphere Studies in Avian Biology No. 36. Cooper Ornithological Society.

- ^ Niles, L., Bart, J., Sitters, H., Dey, A., Clark, K., Atkinson, P.; et al. (2009). "Effects of horseshoe crab harvest in Delaware Bay on red knots: are harvest restrictions working?". BioScience. 59 (2): 153–164. doi:10.1525/bio.2009.59.2.8.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- (Red) Knot – Species text in The Atlas of Southern African Birds.

- Calls of Red Knot (Xeno-Canto)

- Cornell Lab of Ornithology – Red Knot

- USGS – Red Knot Information

- eNature.com – Red Knot

- In Search of the Red Knot-New Jersey Fish and Game

- US Fish and Wildlife Service

- The Shorebird Project

- Red Knot An Imperiled Migratory Shorebird in New Jersey

- RedKnot.org links to shorebird recovery sites, movies, events & other info on Red Knot rufa & horseshoe crabs.