Retina horizontal cell

This article is missing information about Error: you must specify what information is missing.. (February 2009) |

| Horizontal Cell | |

|---|---|

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D051248 |

| NeuroLex ID | nifext_40 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

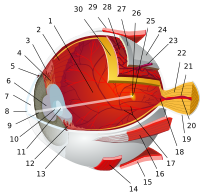

Horizontal cells are the laterally interconnecting neurons having cell bodies in the inner nuclear layer of the retina of vertebrate eyes. They help integrate and regulate the input from multiple photoreceptor cells. Among their functions, horizontal cells are responsible for allowing eyes to adjust to see well under both bright and dim light conditions. Horizontal cells are inhibitory interneurons that release GABA upon depolarization.

The four types of retinal neurons are bipolar cells, ganglion cells, horizontal cells, and amacrine cells.

Organization

There are three basic types of cells, designated HI, HII and HIII. The selectivity of these three horizontal cells, towards one of the three cone types, is a matter of debate. According to studies conducted by Boycott and Wassle neither HI cells nor HII cells were selective towards S,M, or L cones. By contrast, Anhelt and Kolb claim that in their observations HI cells connected to all three cone types indiscriminately, however, HII cells tended to contact S cones the most. They also identified a third type of horizontal cell, HIII, which was identical to HI but did not make contact with S cones.

HII cells also make connections with rods, but do so far enough away from the horizontal cell's soma such that they do not interfere with the activities of the cones.

Horizontal cells span across cones and summate inputs before feeding back onto the photoreceptor cells, hyperpolarizing them. The exact mechanism by which the horizontal cells induce this hyperpolarization is uncertain, but two mechanisms are possible. In the first, hyperpolarization is proposed to be mediated synaptically by the release of GABA by horizontal cells that acts on the photoreceptor cells. In a second option, hyperpolarization occurs non-synaptically by a form of ephaptic transmission in which hemichannels on the horizontal cell dendrites modulate the extracellular potential immediately surrounding photoreceptor terminals.[1] It is worth noting that these two mechanisms are not mutually exclusive and hyperpolarization likely occurs through the combined effects of each of them. The horizontal cells arrangement together with the on-center and off-center bipolar cells that receive input from the photoreceptors constitutes a form of lateral inhibition, increasing spatial resolution at the expense of some information on absolute intensity. The presence of highly polarized retina horizontal cells provides the eye with contrast sensitivity and an enhanced ability to discriminate differences in intensity.

There is a greater density of horizontal cells towards the central region of the retina. In cat retina it is observed that there is a density of 225 cells/mm2 near the center of the retina and a density of 120 cells/mm2 in the peripherals.[2]

Horizontal cells and other retinal interneuron cells are less likely to be near neighbours of the same subtype than would occur by chance, resulting in ‘exclusion zones’ that separate them. Mosaic arrangements provide a mechanism to distribute each cell type evenly across the retina, ensuring that all parts of the visual field have access to a full set of processing elements.[3] MEGF10 and MEGF11 transmembrane proteins have critical roles in the formation of the mosaics by horizontal cells and starburst amacrine cells in mice.[4]

Functional properties

Horizontal cells are depolarized by the release of glutamate from photoreceptors, which happens in the absence of light. Depolarization of a horizontal cell causes it to release the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA on an adjacent photoreceptor. GABA inhibits this photoreceptor, effectively hyperpolarizing it. Conversely, in the light a photoreceptor does not release or it releases less glutamate onto the horizontal cell, which hyperpolarizes it and prevents or lowers the release of inhibitory GABA on the adjacent photoreceptor. We therefore have the following negative feedback.

Illumination Center photoreceptor hyperpolarization horizontal cell hyperpolarization Surround photoreceptor depolarization

One hypothesis [5][6] for facilitation by the horizontal cells proceeds as follows. Assume we have 10 photoreceptors, one hyperpolarizing (H) bipolar cell, and one horizontal cell. All ten photoreceptors connect to the horizontal cell, and the middle photoreceptor () connects to the bipolar cell. The surrounding cells, which represent the outer receptive field, will be designated then we can explain an off-centre arrangement as follows. If light is shone onto the then

- is activated by light and therefore hyperpolarizes

- reduces its release of glutamate

- Reduction of glutamate hyperpolarizes the H bipolar cell

- Reduction of glutamate hyperpolarizes the horizontal cell and it reduces release of GABA

- Since is still releasing glutamate, reduction in GABA is marginal

If the light is shone onto only but not then:

- is activated and therefore hyperpolarizes

- reduce their release of glutamate

- The reduction of glutamate hyperpolarizes the horizontal cell

- The horizontal cell reduces its release of GABA

- The reduction of GABA generally promotes the depolarization of adjacent photoreceptors

- However, because are illuminated they are strongly hyperpolarized by phototransduction - therefore a reduction in GABA is insufficient to make depolarise

- But, because is already in darkness, the reduction in GABA levels is effective at causing to depolarise

- releases glutamate

- H Bipolar cell is depolarized

To explain diffuse light, then we consider both cases together, and as it turns out, the two effects cancel each other out, and we get little or no net effect.

See also

References

- ^ Sohl, G; Maxeiner, S; Willecke, K (March 2005). "Expression and functions of neuronal gap junctions". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 6: 191–200. doi:10.1038/nrn1627.

- ^ Wassle, H.; Riemann, H. J. (22 March 1978). "The Mosaic of Nerve Cells in the Mammalian Retina". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 200 (1141): 441–461. doi:10.1098/rspb.1978.0026.

- ^ Wassle, H.; Riemann, H. J. (22 March 1978). "The Mosaic of Nerve Cells in the Mammalian Retina". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 200 (1141): 441–461. doi:10.1098/rspb.1978.0026.

- ^ Kay, Jeremy N.; Chu, Monica W.; Sanes, Joshua R. (March 2012). "MEGF10 and MEGF11 mediate homotypic interactions required for mosaic spacing of retinal neurons". Nature. 483: 465–9. doi:10.1038/nature10877. PMID 22407321.

- ^ Werblin, F.S.; Dowling, J.E. (1969). "Organization of the retina of the mudpuppy, Necturus maculosus. II. Intracellular recording". J Neurophysiol. 32 (3): 339–355. PMID 4306897.

- ^ Werblin, F.S. (1991). "Synaptic connections, receptive fields, and patterns of activity in the tiger salamander retina". Invest Ophthal Vis Sci. 32 (8): 459–483. PMID 2001922.

- Nicholls, John G.; A. Robert Martin; Bruce G. Wallace; Paul A. Fuchs (2001). From Neuron to Brain. Boston, Massachusetts: Sinauer Associates, Inc. ISBN 0-87893-439-1.

- Masland RH (2001). "The fundamental plan of the retina". Nat. Neurosci. 4 (9): 877–86. doi:10.1038/nn0901-877. PMID 11528418.

- Dacey, Dennis M (1999). "Primate Retina: Cell Types, Circuits and Color Opponency". Progress in Retinal and Eye Research. 18 (6): 737–763. doi:10.1016/S1350-9462(98)00013-5. PMID 10530750.