Retrocomputing

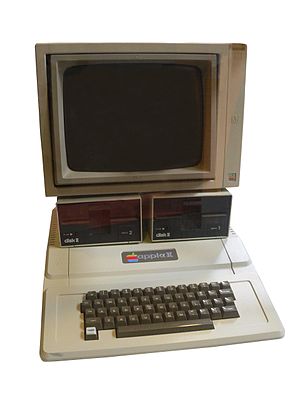

Retrocomputing is the current use of older computer hardware and software. Retrocomputing is usually classed as a hobby and recreation rather than a practical application of technology; enthusiasts often collect rare and valuable hardware and software for sentimental reasons.[1]

Occasionally, however, an obsolete computer system has to be "resurrected" to run software specific to that system, to access data stored on obsolete media, or to use a peripheral that requires that system.

Hardware retrocomputing

[edit]Historic systems

[edit]Retrocomputing is part of the history of computer hardware. It can be seen as the analogue of experimental archaeology in computing.[2] Some notable examples include the reconstruction of Babbage's Difference engine (more than a century after its design) and the implementation of Plankalkül in 2000 (more than half a century since its inception).

"Homebrew" computers

[edit]

Some retrocomputing enthusiasts also consider the "homebrewing" (designing and building of retro- and retro-styled computers or kits), to be an important aspect of the hobby, giving new enthusiasts an opportunity to experience more fully what the early years of hobby computing were like.[1] There are several different approaches to this end. Some are exact replicas of older systems, and some are newer designs based on the principles of retrocomputing, while others combine the two, with old and new features in the same package. Examples include:

- Device offered by IMSAI, a modern, updated, yet backward-compatible version and replica of the original IMSAI 8080, one of the most popular early personal systems;

- Several Apple 1 replicas and kits have been sold in limited quantities in recent years, by different builders, such as the "Replica 1", from Briel Computers;[3]

- A currently ongoing project that uses old technology in a new design is the Z80-based N8VEM;

- The Arduino Retro Computer kit is an open source, open hardware kit you can build and has a BASIC interpreter.[4] There is also a version of the Arduino Retro Computer that can be hooked up to a TV;[5]

- There is at least one remake of the Commodore 64 using an FPGA configured to emulate the 6502;[6]

- MSX 2/2+ compatible do-it-yourself kit GR8BIT, designed for the hands-on education in electronics, deliberately employing old and new concepts and devices (high-capacity SRAMs, micro-controllers and FPGA);

- The MEGA65 is a Commodore 65 compatible computer;[7]

- The Commander X16 is an ongoing project by David Murray that hopes to build a new 8-bit platform inspired by the Commodore 64, using off the shelf modern parts.[8][9][10][11]

- The C256 Foenix and its different versions is a new retro computer family based on the WDC65C816. FPGAs are used to simulate CBM custom chips and has the power of an Amiga with its graphic and sound capabilities.

- Grant Searle collection of homebrew 8-bit projects.[12]

Software retrocomputing

[edit]As old computer hardware becomes harder to maintain, there has been increasing interest in computer simulation. This is especially the case with old mainframe computers, which have largely been scrapped, and have space, power, and environmental requirements unaffordable by the average user. The memory size and speed of current systems enable simulation of many old systems to run faster than that system on original hardware.[13][14]

One popular simulator, the history simulator SIMH, offers simulations for over 50 historic systems, from the 1950s through the present. The Hercules emulator simulates the IBM System/360 family from System/360 to 64-bit System/z. A simulator is available for the Honeywell Multics system.

Software for older systems was not copyrighted, and was open source, so there is a wide variety of available software to run on these simulators.

Some emulations are used by businesses, as running production software in a simulator is usually faster, cheaper, and more reliable than running it on original hardware.[citation needed]

In popular culture

[edit]In an interview with Conan O'Brien in May 2014, George R. R. Martin revealed that he writes his books using WordStar 4.0, an MS-DOS application dating back to 1987.[15]

US-based streaming video provider Netflix released a multiple-choice movie branded to be part of their Black Mirror series, called Bandersnatch. The protagonist is a teenage programmer working on a contract to deliver a video-game adaptation of a fantasy novel for an 8-bit computer in 1984. The multiple storylines evolve around the emotions and mental health issues resulting from a reality-perception mismatch between a new generation of computer-savvy teenagers and twenty-somethings, and their care givers.

Education

[edit]Due to their low complexity together with other technical advantages, 8-bit computers are frequently re-discovered for education, especially for introductory programming classes in elementary schools.[citation needed] 8-bit computers turn on and directly present a programming environment; there are no distractions, and no need for other features or additional connectivity. The BASIC language is a simple-to-learn programming language that has access to the entire system without having to load libraries for sound, graphics, math, etc. The focus of the programming language is on efficiency; in particular, one command does one thing immediately (e.g. COLOR 0,6 turns the screen green).

Reception

[edit]Retrocomputing (and retrogaming as aspect) has been described in one paper as preservation activity and as aspect of the remix culture.[16]

See also

[edit]- History of computing hardware

- Vintage Computer Festival

- Computer History Museum

- Computer Conservation Society

- Living Computers: Museum + Labs

References

[edit]- ^ a b "The Retrocomputing Museum". Catb.org. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- ^ Cignoni, Giovanni A.; Gaducci, Fabio (2012). "Experimental Archaeology of Computer Science". Atti della Società Toscana di Scienze Naturali Residente in Pisa Memorie Serie B (119): 111–116. doi:10.2424/ASTSN.M.2012.17.

- ^ "Briel Computers". www.brielcomputers.com.

- ^ "Arduino Retro Computer with SD card and LCD display and Keyboard input with BASIC interpreter". amigojapan.github.io. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- ^ "Arduino Retro Computer TV". amigojapan.github.io. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- ^ "C-one Reconfigurable computer". Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- ^ "MEGA65 - (MOST PROBABLY) THE BEST COMPUTER". mega65.org.

- ^ "Project Commander X16 | Retro Summit". Retrieved 2019-11-02.

- ^ Murray, David (February 19, 2019). "Building my dream computer - Part 1". YouTube. Archived from the original on October 3, 2022. Retrieved 2022-10-03.

- ^ Murray, David (September 12, 2019). "Building my Dream Computer - Part 2". YouTube. Archived from the original on October 3, 2022. Retrieved 2022-10-03.

- ^ Murray, David (October 12, 2022). "The Commander X16 has finally arrived!". YouTube. Archived from the original on October 28, 2022. Retrieved October 28, 2022.

- ^ "Grant's HOMEBUILT ELECTRONICS". searle.wales.

- ^ Trimble jr, George R. (September 1974). "EMULATION of the IBM SYSTEM/360 on a MICROPROGRAMMABLE COMPUTER". MICRO 7: Conference Record of the 7th Annual Workshop on Microprogramming: 141–150. doi:10.1145/800118.803854. S2CID 5984264.

- ^ Burnet, Maxwell M.; Supnik, Robert M. (1996). "Preserving Computing's Past: Restoration and Simulation" (PDF). Digital Technical Journal. 8 (3): 23–38.

- ^ Lily Hay Newman (14 May 2014). "George R.R. Martin Writes on a DOS-Based Word Processor From the 1980s". Slate. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- ^ Takhteyev, Yuri; DuPont, Quinn (2013). "Retrocomputing as Preservation and Remix". iConference 2013 Proceedings. Fort Worth, Texas: iSchools. pp. 422–432. doi:10.9776/13230 (inactive 1 November 2024). hdl:2142/38392.

{{cite conference}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link)

External links

[edit]- Retro Computer Museum, a computer museum in Leicestershire, UK with regular "come and play" open days

- Retrocomputing Museum for re-implementations of old programming languages

- RETRO – German paper mag about digital culture

- The Centre for Computing History The Centre for Computing History – UK Computer Museum

- Living Computer Museum Request a Login from the LCM to interact with vintage computers over the internet.

- bitsavers Software and PDF Document archive about older computers

- Vintage Computing Resources Active resources for retrocomputing hobbyists

- Learning to code in a “retro” programming environment

- Beginning Programming Using Retro Computing

- LOAD ZX Spectrum Museum, a retro computing museum in Portugal mostly focused on the Sinclair line of computers